Baker’s Tomb one of Rome’s many ancient historical secrets

They say living in Rome is like living in an outdoor museum. It’s true. Hide from the rain in a church, look up and you’re standing under a Caravaggio painting. Stop for traffic in the middle of the street and you’re next to a Bernini fountain.

But living in Rome is also like living in an open history book. A lot of it is in your face. The Colosseum, Castel Sant’Angelo, Il Vittoriano, St. Peter’s, they all can be seen from nearly every hill in the city. My Testaccio neighborhood is dominated by Piramide, a 120-foot-high pyramid dedicated in 12 B.C. to a 1st century B.C. magistrate named Gaius Cestius. It stands out in Testaccio like the Transamerica building in San Francisco.

What I love about Rome’s history is the subtle of it all. Standing on nearly any street corner, you have no idea the importance of that spot 2,000 years ago. All you have to do is look around. Around the corner from my apartment is the remains of a stone wall. It was part of the warehouse they called Porticus Aemilia. It was built in 174 B.C. and stored grain, wine and olive oil, among other goods, during Ancient Rome. Julius Caesar used to come by and check the inventory. Julius Caesar! In my ‘hood! Every day, I walk on the same path he did.

Yesterday I took another trip down a 2,000-year-old memory lane. It’s at the scruffy axis of Piazza di Porta Maggiore, banked on two sides by the Aurelian Wall built to encircle the seven hills of Rome in the 3rd century B.C. It was a major road junction and remains that today with Via Prenestina, Via Casilina, Via Porta Maggiore and Via Giovanni Giolitti colliding near Termini train station. It’s a hodgepodge of bus and tram stops, a hangout for poor immigrants and littered with trash and weeds. Grand Central Station this is not.

But 2,000 years ago, a man erected one of the grandest tombs of Ancient Rome. And it remains here today.

His name was Marcus Vergilius Eurysaces. He was a Greek slave who, when freed, could continue his profession as a baker but could not earn Roman citizenship until …

… he baked 100 bushels of bread a day — single handedly. Furthermore, he had to sell the bread to the state, at a larcenously low price, for at least three years. Yes, in many ways, Ancient Romans were complete unadulterated swine.

Eurysaces kneaded and baked, baked and kneaded. Soon, he found himself with Roman citizenship and a thriving bakery. Bread was a valuable foodstuff in Ancient Rome and by 30 B.C., Eurysaces had become one of the top bakers in town. He became rich. So, matching some of the egos in the Roman Senate, he purchased a plot of land near one of the main gates of Rome. Why?

So he could build himself his own tomb.

(Yes, this is the second blog in a row on Roman tombs. Last week I survived a hacker in my Hotmail account, and I’m in a very dark mood. Bear with me. It helps writing about the dead.)

On a gray chilly Sunday, I took the No. 3 tram from a stop across a piazza from the Piramide. The tram wound past Circo Massimo where they held the chariot races, skirted the green expanse of Monte Celio and went by the Colosseum before chugging through the gritty lower-class neighborhood south of the train station. We stopped in the middle of the piazza surrounded by the old Roman wall.

Here is where Ancient Rome has lost its historical charm. I stepped off the tram and a Bangladeshi beggar approached me with a wide-eyed, exasperated look and a sign reading, “HO FAME!” (I’M HUNGRY!). Two gypsy women I saw moments earlier washing their hands in a public cistern shuffled past me looking at the ground for anything worth collecting.

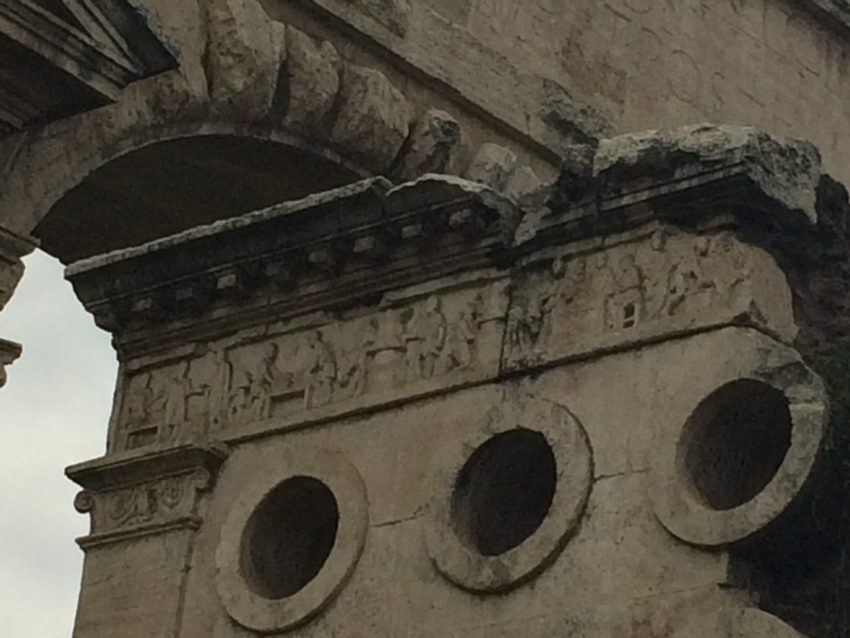

However, I looked above me and there it was. Standing 33 feet high atop a series of strong round columns, stood Eurysaces’ tomb. Surrounded by weeds and a crude, short-iron gate, it looked like a post-apocalyptic ruin of a civilization that prided itself on food. On its sides are a series of huge round holes, which Eurysaces wanted to represent kneading troughs for bread loaves. Later archeologists measured them and realized they represent the exact size for one unit of grain.

Above the holes are a series of graphic reliefs showing the bread-making process. It was Eurysaces’ nod to an Ancient Roman population that was largely illiterate. An inscription below the loaves reads, “Est hoc monimentvm marcei vergilei everysacis pistoris redemptoris apparet” (“This is the monument of Marcus Vergilius Eurysaces, baker, contractor, public servant.”)

Next to it stands a huge double archway built by Emperor Honorius in 400 A.D. and later used as a quarry. During many future excavations, found nearby Eurysaces’ tomb was an urn. It was in the shape of a bread basket.

I did what I usually do when I make a new little discovery in Rome. I looked up and stare at 2,000 years worth of history. Then I walked to a tram stop and joined a mob of Bangladeshis, Pakistanis and Indians, like most Rome residents unlikely aware of the historical significance of the monument hovering above them.

I headed home. I wanted to buy some bread.

December 8, 2015 @ 3:10 am

Those were the days, when the Leader (Emperor/Caesar/King/Capo) would stop by to check on his stores. Imagine!

I used to give history and art tours at the U.S. Embassy, and the site dates back to Julius Caesar and his buddy, Sallustiius.One day I must write about that bit of history. Thanks for the inspiration!

August 22, 2017 @ 6:20 pm

Love the story about baking 100 loaves a day to gain citizenship … but I can’t find the story anywhere else … where is a good source?

August 22, 2017 @ 7:45 pm

I’m on vacation in Maine and I’ll get the source after I return on the 29th.