Baku: The war is over and the city’s flames rise again

BAKU, Azerbaijan – I am an intrepid traveler with an almost macabre fascination with former communist countries. It’s not the inner Marxist in me. The mix of new West and old East simply lures me into old oppressed societies I studied in my native Oregon’s relative lap of luxury in the 1970s.

Every trip to the old Eastern Bloc has been met with jarring polarity. I’d sit in a neon bar built, like, the day before, and talk to a woman my age who spent parts of her youth standing in line for tomatoes.

Then through the window we’d see a heavily pierced, skateboarding teen-ager who didn’t know Karl Marx from Carl Sagan.

On the shores of the Caspian Sea sits a city that takes contrasts to a new level. The city of Baku is like an old tree, displaying layers of its oft-brutal history in one snapshot. It’s part grainy black-and-white and part Las Vegas light show.

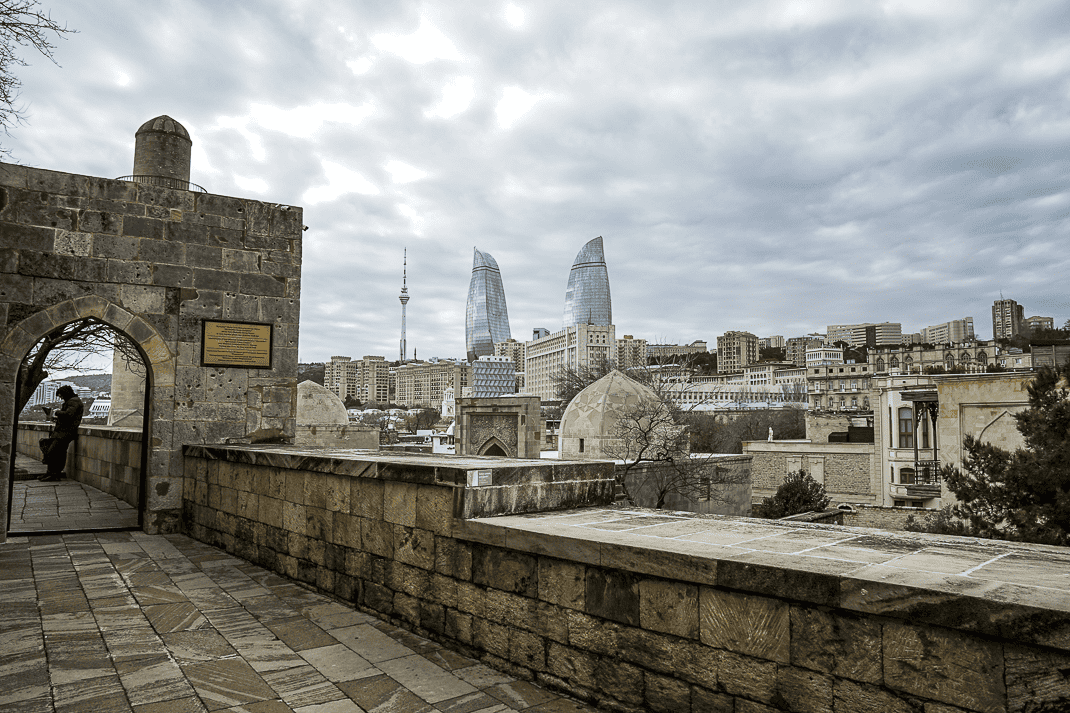

I found that sweet spot on last week’s trip to Azerbaijan. I stood at the top of the Palace of Shirvanshahs, a giant pile of sandstone domes, walls and outside walkways that was the seat of the Shirvanshah family’s ruling dynasty during the Middle Ages.

Off in the distance was Baku history at a single glance.

Just beyond the palace’s beige domes and giant arches is a massive white administrative building almost the length of a city block. With a red roof, this is classic architecture of Czarist Russia which ruled Azerbaijan with an iron fist in the late 19th and early 20th centuries during its control of its huge oil reserves.

Next to it is a series of drab, dirty beige, 10-12-story apartment buildings, the kind you find everywhere from Poland to Vladivostok. Communism is to global architecture what Crocs are to world fashion. They’re functional but that’s it. Squirrels have more interesting homes.

But behind the monotonous strings of darkened windows stands the symbol of the new Baku. The Flaming Towers, three giant glass spires, curvy and sinewy like Azerbaijan’s natural gas flames it represents, dominate the Baku landscape from atop a hill.

At sunset, the towers’ light show alternates between orange and red rising flames, the Azerbaijan flag and the silhouette of a man waving the flag. Built in 2012, the towers, ranging from 28 to 32 stories, and various other modern skyscrapers sprinkled around town make Baku look like a poor man’s Dubai with almost matching bling.

“You can see Baku’s transformation over 600 years,” said Gani, our young city walking tour guide.

Baku’s lure

Why Baku? I was on my way to Tbilisi in neighboring Georgia for Traverse’s annual travel bloggers conference last weekend. Marina had always wanted to see Baku as its skyline and watery shores provided the perfect canvas for her photographic expertise.

We came at a good time. In September, Azerbaijan had defeated Armenia and reclaimed the disputed region of Nagorno-Karabakh. Azerbaijanis were giddy and friendly and open. But no one was happier than president Ilham Aliyev who went into the region’s capital of Stepanakert and threw a parade, which surely went over well with the army of ethnic Armenians trudging to Armenia where they had no homes or jobs.

Aliyev doesn’t care. He’s expected to win today’s presidential election by the length of the country’s average pipeline.

What we found is a capital on the verge of the 22nd century – and a strong hold to its violent past. Azerbaijan has grown into an upper-middle income country thanks to natural gas reserves providing two-thirds of its income.

It has embraced tourism to diversify. Last year 1.7 million people visited Azerbaijan, a 30 percent increase from 2022. Unemployment in Azerbaijan over the last 10 years averaged only 5.3 percent, well below Europe’s average of 7.4

We could sense the wealth and allure. Baku entices visitors with baubles. We spent a chilly afternoon in the low 40s walking along Baku Bulvar. Hard on Baku Bay, Bulvar stretches two miles (3.75 kilometers). While it dates back 120 years, it is modernizing as I’m writing this. At one end, the Crescent Moon Building was nearing completion. It will be one of the world’s oddest hotels: a giant, perfectly round hotel in the shape of an inverted crescent moon representing the crescent on the national flag.

On the other end is the Venezia Lounge, a new restaurant where people can take imitation gondolas up and down its long canals and under its bridges, passing outside tables with white tablecloths. Just beyond it is the Carpet Museum, built in 2014 inside a building shaped like a roll of carpet.

Anchoring it all on the shores of the bay is the Caspian Waterfront Mall, filled with all the usual mall chains you could find in Santa Monica or Singapore. The difference is this five-story mall is shaped like a gigantic multi-petaled flower.

We stood on the huge boardwalk in front of the mall and saw Azerbaijani shoppers feeding a wild squadron of frenzied seagulls with breadcrumbs. Well after sunset, we climbed atop a bridge near the Venezia and watched the Flaming Towers turn Baku’s sky into a giant star-studded movie screen.

Azerbaijan is known as the “Land of Fire.” But Baku is informally known as the “Cleanest City in the World.” It may be. The streets, even in its Old Town, are so spotless we could eat rice pilaf off the sidewalk. We often saw women in fluorescent green vests sweeping tiny leaves from gutters.

And no, these sweepers aren’t society’s lowest rung. The government gives these workers incentives, such as medical benefits and college tuition for their children. Coming from Rome, where seagulls sometimes fight wild boars for food from overflowing dumpsters, this felt like going from Tijuana to San Diego.

Azerbaijan is serious about conservation and the environment. In November, it will host the COP29 climate change summit.

As Reza Deghati, the famous French-Iranian photographer who spent a year photographing the Caspian region for National Geographic, once told Azerbaijan International, “Baku is like an old forgotten book that you discover in your grandmother’s attic. Once you’ve wiped off the dust and delved into its pages, you stand amazed at its treasures.”

Secular Islam

Azerbaijan was my 19th Muslim country. None was more secular. This country of 10 million people is 96 percent Muslim. Yet only 1 percent of the Muslims visit a mosque at least once a week. The Koran tells Muslims to pray five times a day. In some cities, particularly Istanbul, when the imams in thousands of mosques do their call to prayer, it sounds like a giant air raid siren.

In our five days in Baku, I heard the call to prayer once. I saw few mosques. The imams do not use loudspeakers. Worshippers must enter the mosques to hear the prayer.

“We are a secular country like Turkey and Italy and France,” Gani said.

We didn’t see a single burka. Women, blessed with beautiful dark eyes and thick, long black hair, wore fashionable shoes and sexy clothes. The only women covering their hair were tourists from more conservative Middle East countries and young locals following a recent fashion trend called “Islamic chic.” Eighty percent of Azerbaijan’s health and education jobs are filled by women.

It provides for a healthy nightlife. After spending nearly two weeks in Algeria in December searching for a beer, I found myself in Barfly, empty but one of Baku’s teeming hotspots. I loathe nightclubs. House music makes me search for sharp objects that fit deep into my ears. But on a late afternoon to escape the cold, they are welcome havens.

The five-year-old nightclub has a long back-lit bar with the odd decoration of articles about Azerbaijan oil news hanging on the walls. I ordered a Liquor Store Tales, a tall monstrosity of gin, raspberry liqueur and hibiscus. The bartender, a young fit man around 30 with a stylish goatee, told us to come back around 1 a.m. if we want to dance.

I looked around. I saw no dance floor. Just tables.

“They dance around the tables,” he said.

Old Town

If cities were cars, Baku would be an F1. the kind that fly around the city’s wide picturesque boulevards every April in the Baku Grand Prix. Even during Soviet occupation, oil and gas reserves fueled Baku at full speed ahead. Oil in Azerbaijan goes back thousands of years when they used it for lamp fuel and medicine. In the 19th century, it developed the world’s first oil well and first oil tanker. It had electricity well before many parts of the USSR. From the 1850s to 1903, Baku’s population grew from 7,000 to 300,000.

When Czarist Russia came to Azerbaijan to find walnut trees for its rifles, it stumbled onto Baku’s oil industry. By 1884, Baku supplied a quarter of Russia with oil. By 1900 it supplied half the world.

In fact, during World War II, Adolf Hitler was too busy trying to capture Baku’s oil supply to aid the German Sixth Army which was getting creamed in Stalingrad. Hitler shouted at a top commander, “Unless we get the Baku oil, the war is lost!”

Today, Azerbaijan supplies only 1 percent of the world’s oil. But it is enough to fuel many new businesses that keep popping up like flowers. Seemingly every place we went, from restaurants to bars to shops, had been built in the last 10 years.

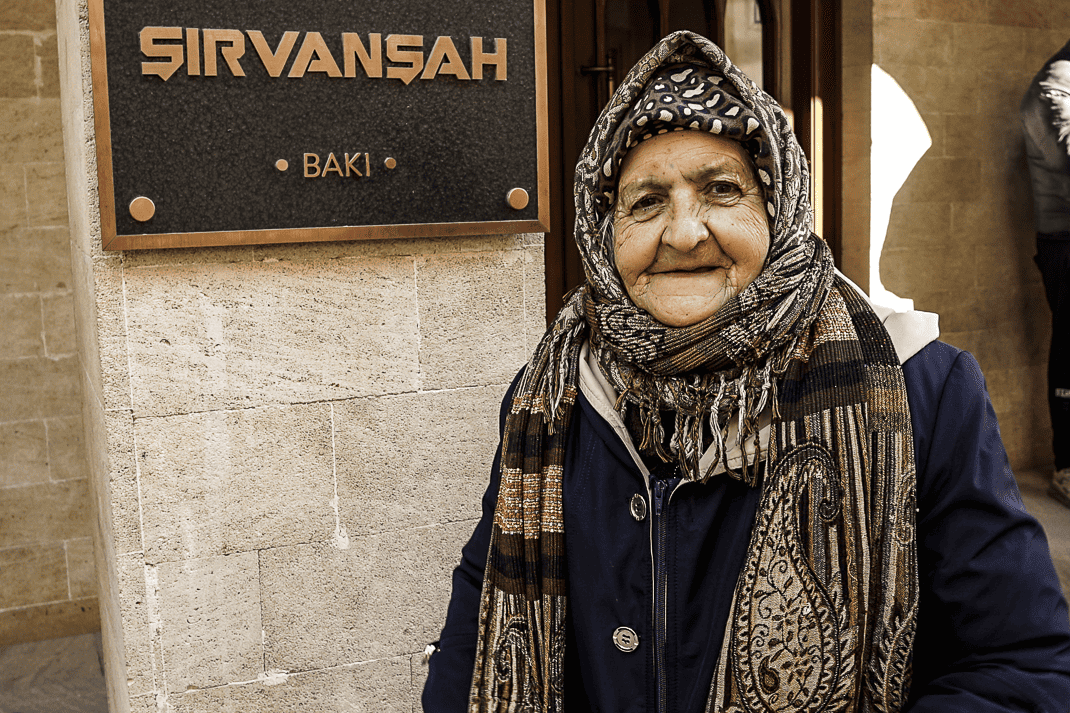

Yet Old Town has kept its mysterious charm. Our Shirvanshah Hotel was right in the heart where narrow alleys between matching centuries-old limestone buildings crisscross around the palace.

Of the Old Town’s original 1,500-meter-long wall, 500 meters still exist. Inside are a warren of boutique shops, cafes and restaurants cooking Azerbaijan’s highly underrated food.

At Cizz-Bizz, run by an Azerbaijan kickboxing champion, I had quzu nar qovurma, lamb in a sauce of pomegranate, chestnuts and onion. At Floors, a hip, four-floor bar with oil paintings of celebrities and rooftop views of the palace, I had dushbara, a soup of meat-filled dumplings in a hot broth sprinkled with parsley.

We ate in peace. That’s a new concept in Azerbaijan.

The war

The end of their Armenian conflict has left Azerbaijan at peace for the first time in 30 years although simmering tensions remain in Nagorno-Karabakh. It’s life in the Caucuses, one of the toughest neighborhoods on the planet’s regional map.

Let’s see. Let’s look at its neighbors. Russia, Armenia, Georgia, Iran and Turkey. Or as Gani eloquently described, “Turkey’s government is like a mafia godfather. People think Russia is like a big brother. I think it’s more like an abusive uncle. Iran? A toxic boyfriend. Georgia is a Catholic marriage.

“Armenia? We hate each other and kill each other every day.”

The Armenians, who are Christians, had suffered plenty. After the fall of the Ottoman Empire, the Turkish government killed 1.5 million Armenians still living in Ottoman territory from 1915-1922. Many remained in the Nagorno-Karabakh, a 1,700 square mile region 90 miles (150 kilometers) from the Armenian border.

With the backing of the Islamophobic Russian government, 120,000 Armenians lived there and in 1991 declared independence in an area Azerbaijani always claimed was theirs. Between 28,000-34,000 people were killed during continuous conflict between 1988-1994, including 1,264 Armenian civilians.

But Azerbaijani suffered also. On Feb. 26, 1992, in the Azerbaijani stronghold of Khojaly inside Nagorno-Karabakh, Armenians killed 613 Azerbaijani civilians, including 63 children, according to Azerbaijani authorities.

Then last September, Azerbaijan’s government, which had accused the Armenians of “savagery,” blocked food and supplies to the region before attacking on Sept. 27. Since September, more than 100,000 ethnic Armenians have returned to their homeland where they haven’t lived in a generation. Most have no homes or jobs.

“It’s the first time in 200 years we won a war,” Gani said, “and took our lands back.”

Now a Swiss company wants to pump $175 billion into developing the region. One tip: They may want to first dispose of the thousands of remaining mines.

Chalk it up to another line in the tree in the Land of Fire.

If you’re thinking of going …

How to get there: Azerbaijan Airlines, Turkish Airlines, Pegasus, Wizz Air and easyJet have flights from London. Azerbaijan flies direct. The five-hour, 30-minute flight in June is $659 round trip. WizzAir and Turkish fly with a change in Istanbul for $313.

Where to stay: Shirvanshah Hotel, 1/50 Gesr Stred Baky, 994-50-263-3837, http://rumahotels.az/home/shirvanshah/12, info@shirvanshah.az. Big rooms in the heart of Old Town, walking distance to outside the walls and to Baku Bulvar. I paid €480 for five nights. It has a spa with Jacuzzi, Turkish sauna and regular sauna. Only the sauna worked during our visit.

Where to eat: Cizz-Bizz, 28 Kichik Qala, 994-12-505-5001. All the traditional Azerbaijani specialties, from kebabs to various lamb dishes. Ranges from €10-€35, 9 a.m.-midnight.

Time to go: Avoid July and August. At 28 meters below sea level, Baku is the largest city below sea level in the world. In summer it is steaming. In spring, average highs range from 62-82 with lows 46-65. Last week it ranged from high 30s and low 40s at night to about 50 during day.

For more information: Tourist Information Center, 14 Bulbul Ave., 994-12-498-1244, 9 a.m.-6 p.m. Monday-Friday.

February 7, 2024 @ 1:21 pm

WOW! What a fascinating place. I had heard (seen) pictures of pollution here from the oil fields and all the nodding donkeys. Has that pollution gone?

February 7, 2024 @ 2:08 pm

I had heard nothing of pollution and we saw none of it.