Belgian beer is the toast of the beer world

BRUSSELS — I walked down the creaky staircase to the epicenter of the beer world, like descending into the third circle of heaven. I remember the last time I smelled an aroma of beer this powerful. It was the mid-70s in my fraternity’s party room, a den of destitution so foul we needed the Army Corps of Engineers to clean it every Sunday morning. But this latest beer smell was different. It was of hops and barley, caramel and malt, all as fresh as a bowl of granola.

It was the smell of Belgium.

The Delirium Cafe is the beer capital of the country that’s the beer capital of the world. No country produces better beer than Belgium. No country produces more different beers than Belgium. No bar sells more different beers than Delirium. I know. I asked for a beer list and the harried bartender threw me a book the size of the Brussels telephone directory. It plopped on the wooden bar with the sound of a falling atlas. Inside were — and I am not making this up — 3,162 different beers. About 90 percent are from Belgium.

Numbers are hard to pin down but one source, the website Beerly Coherent, says Belgium, a country the size of Maryland, produces 8,700 beers, including one-time knockoffs. You could live in Belgium 23 years and try a different beer every night yet not go through them all. In Belgium on assignment last week, I peeked under the bottle cap of the world’s greatest beer nation.

I looked around Delirium and the ceiling was covered with beer trays from companies around the country. They seem to have more beer names than towns. There are the beers named for wildlife: Tarantula. Kentucky Monkey. Killer Penguin. There are beers named for monks who started this grand tradition here nearly 1,000 years ago: Brother MarMar. Brother Larry. Father Albert’s Frock. Then there are beers that are just plain gross: Zeus Juice. Chuggit Pucker III. Bucolic Plague.

I asked for a Bush, which is tame in name only. Do NOT confuse it with Busch, which to all those Americans who learned how to drink in the ‘70s through trial and lots of error, was a vile swill that sailors have refused to drink. Belgium’s Bush Blonde is a smooth, viciously strong brew that goes down with 10.5 percent alcohol content. Some Bush versions go up to 12 percent. That’s more than some Italian wines.

However, I was not surrounded by drunks. It was a mixed, reasonably sober crowd. It was both old and young, Belgian and expat, visiting politicos (Brussels is capital of the European Union) and retired journalists (mois). Standing next to me were Lora, a Belgian-Canadian living outside Brussels, and Gabriele, a visiting Italian who spoke Italian to me. When it comes to alcohol, Italians are notorious lightweights. They drink little and have shunned American wines because of their heavier alcohol content. Yet Italy is the fastest-growing beer nation in the world. It has about 650 breweries. Nine years ago, it had only 70. Most of these artisan beers follow the Belgian style of heavier alcohol.

I am pleased to see Gabriele is still standing.

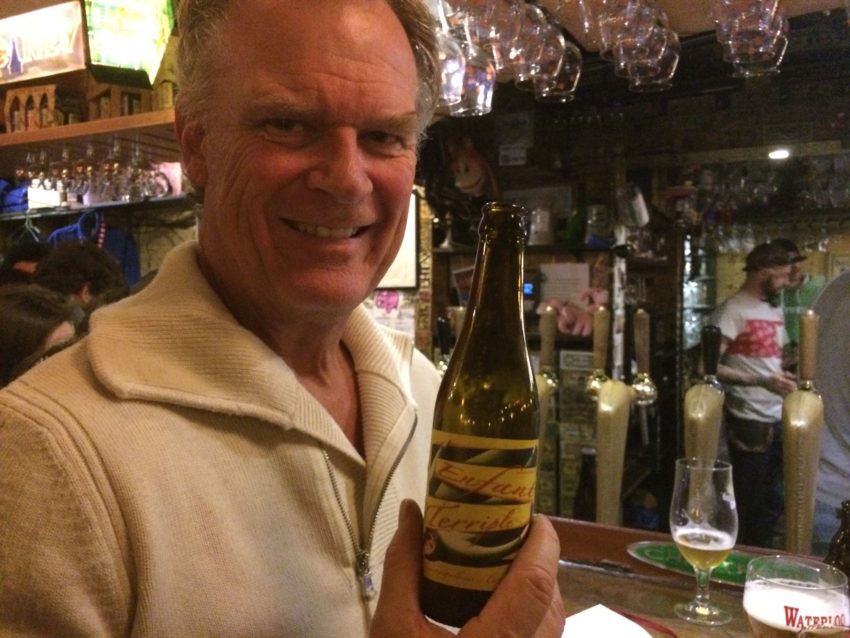

Lora handed me her favorite beer, Enfant Terriple, from DeLeile brewery in Western Flanders in northwest Belgium. Terriple stands for “triple,” meaning the beer has three times the malt as regular beers. At 8.2 percent, it also has nearly twice the alcohol as regular beers and my two years sipping wine in Italy was catching up to me. I wanted to toast the nation of Belgium, or, at least, the bar. I asked Lora how to say “Cheers” in Flemish.

“Here’s how to say it in our dialect,” she said. “‘Op euh bakkes! (Cheers to your f****** face).” She even wrote the asterisks in my notepad.

I fell in love with Belgian beers during my 23 years in Denver while hanging out at my favorite pub, The Cheeky Monk. Its variety of beers directed me down a different, although admittedly wobbly, path through the Belgian beer world. Not all are the sickeningly sweet Stella Artois which is what Belgium exports more than any other beer. The Belgian beer universe has a wide span that has something for every taste bud. After putting a good dent in the atlas-size beer menu in only two nights, here’s a quickie guide to Belgian beer:

WITBIER — Started in the Middle Ages, it’s made from unmalted wheat and orange peel, among other ingredients. It’s very light with as low as 4.5 percent alcohol. Do NOT order this in working-class bars.

WITBIER — Started in the Middle Ages, it’s made from unmalted wheat and orange peel, among other ingredients. It’s very light with as low as 4.5 percent alcohol. Do NOT order this in working-class bars.

BELGIAN PALE ALES — They’re amber to copper in color, like English pale ales, and also low in alcohol content, about 4.5-6 percent. Very popular in the one or two days of the year Belgium is warm. It’s also the style that made Stella Artois famous. Ordering a Stella in Belgium is like ordering a Fosters in Australia or a Budweiser in the U.S.

BELGIAN BLONDE — This is a moderate version of strong pale ales and popular with Europeans used to light pilsner style beers.

BELGIAN STRONG PALE ALES — The most famous is Duvel (“Devil” in Flemish) which has been making inroads in the international market. It’s lighter but bitter.

SEASONAL — Just like it sounds, it’s made by the season, usually in the winter from leftover wheat in the fall.

DUBBEL — The Westmalle monastery developed this in 1926 with an alcohol content of 6-8 percent and it has become hugely popular. Strong and smooth but not packing such a punch that you can’t drink more than two.

TRIPEL — This is when you get into the heavy alcohol. These run about 7-10 percent. They taste thick but explode with flavors yet have virtually no aftertaste.

DARK ALES — These are the heavy hitters, the bouncers of the Belgian beer world. They reach about 12 percent alcohol. Each bottle should come with a breathalyzer.

I have found a different Belgian style for every mood. I drink pale ales in the summer, strong pale ales when I want flavor and dark ales when I don’t have to walk more than two blocks to my home or hotel. I order a St. Bernardus Tripel. It comes in a deep, wide-rimmed glass, one of the thousands of glasses breweries make for each beer. The glass, whether it’s wide-rimmed or tall and fanning out, bring out the best in the head and the aroma. Surprisingly, it does make a difference. You’ll never drink from a plastic cup again.

By now, I can’t tell a Belgian blonde beer from a Belgian blonde period. I have had five Belgian beers in about four hours, each ranging from 6.7 to 10 percent. I am very thankful that I’m drinking on a full stomach. The best way to do that, in Belgium, is line your soon-to-be-flooded stomach with the Belgian national dish: moules-frites (mussels and fries). Mussels, those delicate, shelled seafood delicacies, are all over the short Belgian coast along the North Sea. Most restaurants give you a bucket with more than a pound of mussels, along with a discarding plate and a small prongs.

I started the evening prowling for mussels in the Bourse, a small maze of narrow, cobblestone, pedestrian streets not far from the Grand Place, which Brussels touts as Europe’s most beautiful square. I quickly felt that suffocating feeling of being in a tourist trap when most of the restaurants had barkers trying to lure me in — with perfect English.

“Come join us.” (Dude, your restaurant is empty.)

“Come here. I want to show you something.” (And I’ll show you THIS.)

“A wise decision!” (Yes, I’m walking past you again.)

I finally saw a restaurant packed. I opened the door to Le Marmiton and I heard nothing but French and Flemish, a language nearly identical with Dutch in its complete inability to comprehend it. I saw one table full of Americans talking business. I sat down in a brightly lit and unpretentious eatery and ordered an old standby: a Duvel. At 8.5 percent, it’s the perfect accompaniment to Moules Poulette with onion, celery, parsley, carrots, white wine, oil and cream. For “dessert” I ordered a Grimbergen Dubbel, which comes from the Norbertine abbey in the Brussels suburb of Grimbergen.

Religion and alcohol is a curious mix. In Belgium, the custom goes back to the Middle Ages. During the Plague, a local bishop named St. Arnold convinced locals to drink beer instead of water. Water must be boiled to make beer. Thus, they had safe water to drink. As a convenient plus, the automobile, or breathalyzers, had not been invented yet. Soon hospitable monks started brewing their own beer for guests. They also brewed beer at various alcohol content so they could serve God without falling over a pulpit. Today, many of the bottles have caricatures of fat, and quite happy, monks holding a glass of brew.

I returned to Brussels a few days later and went to the international emporium for men and beer: the sports bar. Fat Boy’s Sports Bar & Grill is an American-style bar draped with banners from obscure European soccer clubs: Bordeaux, Sampdoria, Udinese. One from Duma Warmii is an ode to Piotr, my learned Polish bartender who gave me a seated tour of Belgian beer. He told me he has seen Belgian beer destroy the bravado of more than one visiting soul.

“I see four guys come in and say, ‘We want to try all your Belgian beers!’” he said. “After three or four, they’re completely out. Game is over.”

I told him how the Irish and British pubs in Rome won’t serve the stronger artisan beers that exploded in Italy. “We’re in the business of selling beer,” one Rome bartender told me. “If the beer is too strong, Italians don’t drink many.” Piotr said Belgians come from a different stock. Yes, when you’ve brewed strong beer since the 12th century, you don’t have to settle with Coors Light.

“People here enjoy the different tastes,” he said. “They don’t get drunk.”

He recommended an Ommegang, a nice blonde at 8 percent. I graduated on to a Tongerlo Triple Triple at 9 percent. So strong. So cold. So smooth. I wonder now if a Budweiser would shock my system into convulsions.

A nightcap at Delirium, however, topped my weekend in Belgium. I ordered La Rulles, an 8.5 percent ale that is strong, with lots of malt and no bitterness or aftertaste. Even on a cold night in the low 40s, it’s so refreshing I may have to christen it my favorite beer of all time.

As I licked the inside of my empty glass, a slightly tipsy young tourist asked the overworked bartender in accented English, “What do you recommend?” The bartender looked at him as if he just bit into an onion.

“Do you realize,” he said, “we have 3,000 beers?”

Op euh bakkes, Belgium!