Following in The Beatles’ footsteps through Liverpool

LIVERPOOL, England — I’m standing at Ground Zero of the phenomenon that is The Beatles, feeling more than a bit out of place. For me to visit The Beatles’ birthplace is a little like Donald Trump visiting Lenin’s Tomb. I’m not politically opposed to The Beatles but I’m one of the odd birds who has a unique, admittedly weird, personality trait and am just dumb enough to admit it.

I hate music.

You read that right. There are some of us out there. In the U.S., we’re the quiet guys at the end of the bar watching ESPN. In Rome, it’s not much of an issue. It’s a restaurant town, not a club town. That’s a relief. In the States, I’d have to defend my stance as if I just revealed that I was radioactive, had AIDS and worked for Iranian intelligence. A woman once broke up with me because I didn’t like music. That’s fine. I preferred that option to wasting three hours of my life I’ll never get back watching the Grammys with her.

I blame my parents. Growing up in Eugene, Ore., we never had music in the house. I never heard a song played. Occasionally, I’d hear something from a radio drift out out of a sister’s bedroom. My parents weren’t against music. They just never listened to it. Ever. Instead, we listened to comedy records. Bill Cosby. Jonathan Winters. Bob Newhart. To this day, I’m a comedy club maven. A bad singer can still make people clap at the end of a song; a bad comic can’t make you laugh.

So I’ve drifted through 60 years of life tone deaf to instruments. Singing has no effect on me. None. I don’t subconsciously move when music is heard. I have yawned my way on and off dance floors while looking at my watch waiting for the song to end so I can attempt an intelligent conversation with the one-step goddess who’s ignoring me. Some music is worse than others. I can’t be in the same room with Country Western. The blues are called “blues” for a reason. I thought The Eagles were vile pockmarks on the landscape of international entertainment. I still get the shakes when I hear Don Henley’s grating, blackboard-slashing voice in “Hotel California.”

But I thought The Beatles were OK.

So I came to England on assignment and wanted to visit Liverpool for the first time. It has a lot to offer someone like me. It’s an urban success story. Formerly a gritty, poor, cold and damp port town in northern England, it now sports a revitalized waterfront and more museums than any city in the United Kingdom outside London. It’s one of the world’s soccer hotbeds with two teams dating back to the 19th century. It’s still cold and damp but, like music, I don’t care about weather, either.

What I appreciate about music is it provides a window into a culture. In Liverpool, tracing The Beatles is tracing the ascendancy of the greatest rock group in history. They’re the top-selling band known to man, selling 600 million records. That’s shocking considering they were together only from 1960-70. That’s 10 years. Devo lasted nearly 20. Beatles songs’ staying power is more like Bernini sculptures than music.

I also lean toward The Beatles politically. As a child of the ‘60s, I remember how John Lennon’s “Imagine,” actually written in 1971 after The Beatles disbanded, stood for the anti-war movement better than any song of that era. I firmly believe The Beatles helped end the Vietnam War, the third greatest mistake in American history, next to the Iraqi War and the birth of Don Henley.

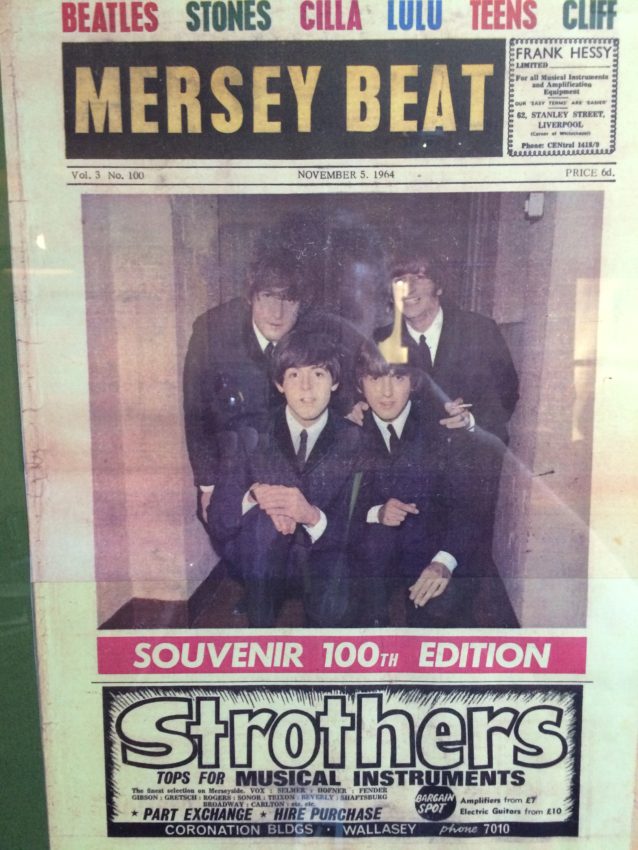

So I followed The Beatles’ footsteps around their hometown which, when they grew up in the ‘40s, was still undergoing urban renewal after getting bombed in World War II. I started at the Mecca of all Beatles’ fans, the Beatles’ museum. Called The Beatles Story and built by the waterfront in 1996, the museum traces the group from start to finish with fascinating Beatles’ paraphernalia scattered around like confetti. It draws 300,000 visitors a year.

Some things I didn’t know about The Beatles (and I bet you didn’t know, either):

* Both Paul McCartney’s and John Lennon’s mothers died when they were teen-agers. Paul’s mother, Mary, a midwife, died of an embolism when he was 14. Julia Lennon, a movie usher, was killed in an auto accident by an off-duty policeman when John was 17.

* In their first performance abroad in 1960, promoters in Hamburg, Germany, changed their name to The Beat Brothers as they thought The Beatles was too confusing.

* The 1967 album, “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band,” which spent 27 weeks at No. 1 in Great Britain, took 700 hours to produce at their Abbey Road studio in London.

When I walked to the ticket counter, a pretty young woman greeted me with a foreign accent nothing like Liverpool’s Liverpudlian. In other words, I understood her. I asked where she was from. She was from Versailles, France, home to the palace where Marie Antoinette was dragged kicking and screaming and soon beheaded in a public square. I asked her why she left a gorgeous place such as Versailles for Liverpool.

“Versailles doesn’t have The Beatles so I had to move here,” she said.

As a museum junkie, I must say The Beatles Story is as well organized as any I’ve seen in the world. It begins when they were kids and ends when they end, finishing off with individual rooms for each member. It even has a picture where it all began. It’s a high-quality, poster-size black and white from July 6, 1957. It shows Lennon at 16, looking as innocent as a Liverpool FC ball boy with a checked shirt and crewcut. He was playing a guitar with his group, the Quarrymen, in a field behind St. Peter’s Church in Liverpool. Wandering by was Paul McCartney who was impressed by this skinny kid, two years his senior playing this cheap guitar.

That night, McCartney went to the Quarrymen’s gig at a church dance across the street. While the group set up equipment, one of McCartney’s classmates at the Liverpool institute, Quarrymen bass player Ivan Vaughan, introduced him to Lennon. McCartney’s guitar playing impressed Lennon so much during an intermission session, he was almost fearful of him joining and stealing the spotlight him. However, that day The Beatles began.

Oh, the cheap guitar? It’s on display in the window. Lennon bought it for 10 pounds (about $14 today). Sotheby’s auctioned it in 1999 for 140,000 (about $200,000).

After Ringo and George joined, they were trying to make a name in arguably the hottest rock ‘n roll hotbed in Europe. In the early 1960s, the museum explained, the city served as the base for about 400 rock groups. The Beatles, however, quickly rose above them all. By the time The Beatles were 18, teenage fans mobbed them during their local gigs. They escaped to a pub called The Grapes. The museum has a replica of the pub’s exterior, complete with a back-lit window sign.

Across the museum’s aisle is another replica. The Cavern was The Beatles’ club. They played there 292 times, producing lines up the block (cover charge when it opened in 1957 was 1 shilling or about 7 cents) and returning even after becoming international household names. The exact replica shows a narrow room with an arched ceiling and small lit stage flanked by arched entries leading to the bar. The museum’s audio guide said the club became so hot and sweaty, The Beatles’ electric guitars sometimes short-circuited from the condensation.

As “A Hard Day’s Night,” “Strawberry Fields Forever” and “Hey Jude” drifted through the air, I followed the windy path through some interesting rooms. There is a gravestone marked Eleanor Rigby. McCartney said he came up with the name Eleanor Rigby on his own as a combination Eleanor Bron, an actress who starred in their 1965 movie “Help!” and Rigby came from a wine store in Bristol, England, where McCartney often visited his girlfriend. Eerily, there really is a Eleanor Rigby grave. It’s dated Sept. 12, 1692. It’s from the graveyard near the church where McCartney first saw Lennon.

There’s a room of the exact interior from the plane The Beatles took on their groundbreaking 1964 tour of the U.S., a lifesize display of the famous “Sgt. Pepper’s” cover and a walkthrough of a yellow submarine.

Then I came across a video. It was a riot. People were passed out, being dragged off by police. Squadrons held back wildly screaming and crying youths. It looked just like the video I saw in Prague about the Velvet Revolution when the students battled police in 1989. The Beatles’ video was nothing of the sort. It was of kids, mostly young women, screaming and crying trying to get The Beatles’ attention during their U.S. tour of ‘64.

It would have been nice if the video guide had more information on the inspirations behind the songs. But at least they didn’t spend one word or one meter of space on the absurd mystery of McCartney’s alleged death. The myth in the late ‘60s veered every one of my junior high friends away from the Vietnam War and onto the various interpretations of the word “walrus.”

Later I broke personal tradition and went to a club. But when in Liverpool, a trip to The Cavern is a must, like seeing St. Peter’s in Rome. It’s an exact replica of the original just a few yards away after it closed in 1973 to build a ventilation shaft. The replica opened in 1984 and, self-proclaiming as “The most famous club in the world,” it is indeed a tourist trap. However, it is not a ripoff. I walked in at about 7 p.m. and there was no line, no cover. I may as well have walked into a pub in Blackpool. I wound down the staircase (the same number of steps as in the original) and saw on stage a young man singing “Proud Mary.”

The Cavern is the epitome of Liverpool’s massive current music scene. It features live music from noon to midnight on weeknights and until 1:30 a.m. on weekends. They’ve had a string of famous acts come through including Elton John and The Who. McCartney still gets on stage whenever he’s in town which is often. They all play some kind of Beatles’ cover and each one points the microphone at the packed crowd whenever they reach famous lines. There is nothing like 100 drunk male tourists screaming, “WE ALL LIVE IN A YELLOW SUBMARINE!”

I bought a reasonably priced pint of French 1664 beer for 3.90 pounds (about $5.60) and sat down next at the same round table as a Danish couple. Neither was a fanatic. Neither do what a work colleague in Las Vegas did: spend a year knitting a quilt depicting the Beatles’ Abbey Road cover and chasing them across the country trying to give it to them. However, history grips even the casual. It gripped me. Sitting in the Cavern, instead of the skinny Liverpudlian on stage singing “Hey Jude,” I pictured the Fab Four in the early ‘60s. I wasn’t surrounded by fat, bald tourists but girls with flip hairdos and pleated skirts.

The Cavern brings back memories even if you’re not English. As the kid played a decent impersonation of “Imagine,” I remembered hearing it as a backdrop to news videos of violent war protests in the U.S. Then came “Revolution.” I remembered it was the first time I ever danced: seventh grade with Karen Nygren. I also remembered looking at my watch. But most of all it reminded me of how exciting Liverpool and life in 1960s England felt like. Rainy days. Strawberry fields. Cold cathedrals. The Beatles weren’t just music. They weren’t just youth and politics. They were Britain. They were England. They were Liverpool.

Finally, after 60 years, I was here.

The next day, my AirBnB host offered a treat. Christine used to work for the city and specializes in The Beatles. Her AirBnB between the fantastic street of Lark Lane and gorgeous Sefton Park, isn’t far from where McCartney and Lennon grew up. In a 45-minute tour, we covered half of their childhoods.

Ever hear “Penny Lane”? Even a musical moron like me has memorized the lyrics. It’s essentially about their childhood in south Liverpool. We drove down the real Penny Lane, a non-descript, middle-class street where they used to hang out. But to get there we had to pass “the shelter in the middle of a roundabout” and, across the street, is a bank where there once was “a banker with a motorcar” and farther down the road is a fire station where there was — again, I’m not making this up — “a fireman with an hourglass.”

Lennon and McCartney came from working-class families but neither was in poverty. Alfred Lennon was merchant seaman and often away. Jim McCartney was a volunteer firefighter and musician. Yoko Ono, Lennon’s wife, bought his house and put in the National Trust. Still standing there on busy Menlove Avenue is a small, pleasant, two-story house with a glassed entryway and a bay window on the second floor. John lived there from 1945-63. That’s 1963, about a year after they became international superstars. As “Penny Lane” proves, The Beatles didn’t forget their roots.

A few blocks away on quieter Forthlin Road is McCartney’s house, a simple two-story brick house with a front lawn edged with white wildflowers. To reach McCartney’s house, Lennon used a shortcut through fields of strawberries. Who knew “Strawberry Fields Forever” was about their childhood?

The pair would hang out in these strawberry fields and “misbehave,” Christine said. Today, a bright red fence guards an overrun field that probably hasn’t seen a wild strawberry for years. No matter. To stare into the greenery and imagine Paul McCartney and John Lennon planning their musical careers together was like looking into the prehistoric cave where they invented the wheel.

Afterward, Christine and I ate at Penny Lane Fish ‘n Chips, serving up the best fish ‘n chips in Liverpool. Run by a Vietnamese lady, the fish ‘n chips is lean and lightly breaded and, unlike most fish ‘n chips in Great Britain, its grease can’t soak through an entire edition of the Sunday Times.

OK, so I admit it. Music does have its appeal. But The Beatles transcend mankind. I found myself Googling Beatles lyrics online. I wanted to know who Sgt. Pepper really was. I thought a lot about England in the ‘60s, about how they changed history, both musically and politically. You may say I’m a dreamer.

But I’m not the only one.