Kerala’s Backwaters a 900-kilometer labyrinth through quiet India

ALLEPPEY, India — One doesn’t have a lot of quiet time in India. It has the world’s seventh largest land mass yet you wonder if it’s big enough for its 1.2 billion people. It always seems ready to burst at the borders, like Grape Nuts falling out of a cereal bowl. Even here in Kerala, India’s least densely populated state, people appear on top of each other. Passengers hang from the steps of trains.

But next to my guesthouse in Alleppey, 150 miles north of India’s southern tip, may be the quietest place in India. It’s where you can hear eagles squawk from miles around, where women in saris gossip quietly across canals and where the tiny ripples from boat paddles have a rhythm all their own.

This was the reason I came to South Asia. They are called the Backwaters. They are a 900-kilometer maze of canals that meander through a thick forest of palm trees. Glassy-smooth lakes flow into rivers that flow into canals so narrow you can touch both sides of the shore. With the lime green palm trees against a turquoise sky, it looks like you combined French Polynesia with Venice and kept out all the tourists.

But you kept the gondolas.

I met my boat captain at 6:30 a.m. I never understood his name but he was a tall, lean man with a gray moustache and gray hair he brushed back atop a long face. He curiously wore a white dress shirt over a black print sarong the Indian men wear tied up like long, baggy shorts. He spoke virtually no English.

My guesthouse is right along the canal so our commute consisted of merely walking behind the house and hopping into his boat. It was about 20 feet long and as narrow as an Olympic scull. But it had the comfort of a gondola. I settled into a padded brown leather seat covered in a colorful print. A long canopy provided a nice cool, shady viewing position. I slipped off my flip flops, put up my feet, took out my camera and got set for the quietest, most beautiful four hours you can spend in India. National Geographic Traveler in 1999 listed it among the 50 Destinations of a Lifetime.

For centuries, the villagers here have used these Backwaters for transportation. Running parallel just about three miles from the Arabian Sea, they consist of five large lakes and 38 rivers. The Backwaters stretch half the length of Kerala state — including practically to my doorstep.

Using a long paddle, the captain wiggled through the narrow canal by my guesthouse and we entered the large canal. It was about 50 meters wide and so quiet I could hear water ripple as he pushed the boat along. The brilliant orange ball of the sun peeked under the giant leaf of a palm tree to the east. It was just getting light and mercifully cool after nearly two weeks of skin-glistening humidity. We passed lone fishermen cruising out in their boats with tiny outboard motors manned by a long stick in the boat’s stern.

At least they had boats. I saw heads bobbing up and down in the water. I thought they were coconuts. They were humans. Men crawled down long round poles deep in the water and coming up holding small fishing nets.

As we cruised along, the sun began to rise over the palm trees, finally illuminating the gray sky with color. Off in the distance I heard the piercing sounds of Hindu music over a loudspeaker. It sounded a bit like a long, melodic prayer but more like a really bad lounge act.

“Temple,” said the pilot as he pointed to a round structure in orange and yellow beyond the palm trees. It was about the only irritating noise I heard all day.

As we made our way down the wide canal, India’s wildlife seemed to wake at the same time. Low-flying birds buzzed our canopy. Kites with their long, glider-like wings, floated aimlessly. Cormorants with their tall regal heads floated low to the water before making quick dives for fish swimming too high to the surface. I heard roosters crowing, more fishing boats buzzing and my pilot’s paddle slowly lapping the water behind me. Maybe this is what Ullas, my meditation instructor, meant when he talked about a “meditative state.” I was halfway between bliss and heaven.

The Backwaters isn’t a Indo Disney ride. For centuries these waters were Kerala’s lone means of transportation. Most of the 10,000 residents along these canals still get around by boat rather than car. Every home, despite the size, seemed to have some kind of craft nearby. Some of the boats were on blocks or had holes sharks could swim through but they were there.

This is life on the river. As we slowly paddled by, women pounded laundry on rocks. Teen-age girls meticulously washed their hair over the water. Shirtless men in their sarong shorts brushed their teeth. The water was not clear but it was not the sludge I’ve seen in other Third World countries. I would swim in it. It was certainly warm enough. When I dipped my hand over the boat, I had to look at the water to see when my hand changed from air to liquid.

This also is not off the beaten path. Big on these waters are houseboats. Yes, you can have a romantic honeymoon in India. Rent a houseboat, complete with rounded bamboo roof, lanais chairs, dining room tables and comfy cabins. Or get two or three couples and share one. I passed some where fat, sunburned Brits held their iPhones up to video the scenes. The houseboat’s handicap, however, is it’s too big to get through the narrow canals which is the Backwaters’ charm.

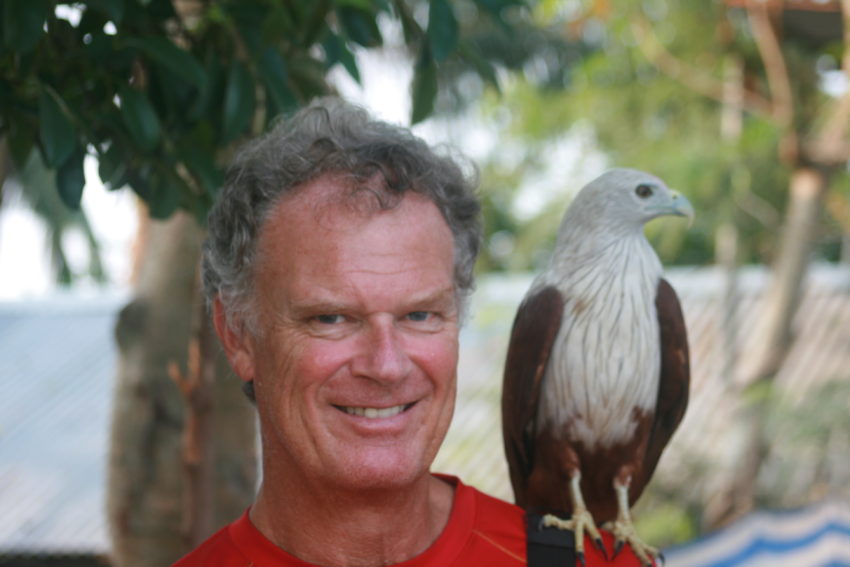

The other charm is the Backwaters seem totally unspoiled. Except for the pink monolith that is the Ramada Hotel off in the distance, the Backwaters are void of lodgings, restaurants and souvenir stands. We stopped for lunch at a broken-down wooden shack with no sign. A tarp covered a locked fence where a young, well-groomed man in his 30s emerged. In very broken English, he said food was coming in five minutes. In the meantime, he walked into his house and emerged with his pet resting on his shoulder: a white eagle.

Yes, eagles are pets here. He said they are not endangered. In fact, as he put it precariously on my shoulder for some schlocky photos, it made the same, “caw! CAWWWWWWW!” sound I heard all day at my beach bungalow in Varkala. Eagles fly around here like crows.

Soon, a middle-aged woman in a tiny motor boat docked and brought a round flat fish to the “cafe” owner. He showed me how he cut off the fins and got it ready for grilling. He fried it in a curry sauce that was just spicy enough to not need anything ice cold. I saw nothing that amounted to a refrigerator. But for a riverside lunch in the middle of rural India, I’ve had worse meals in suburban Denver.

After lunch, the rising sun had slowly turned the gray sky blue. And the heat began socking us in. The pilot put on a multi-colored umbrella hat to keep himself cool. But I couldn’t stay in the shade too long. I crawled to the bow

seat as we slowly meandered down the narrowest of canals. Middle-aged men in immaculate saris squatted on the bank, waving at me as I passed. Then they returned to talking on their cell phones. I wondered what the two attractive women in their 20s were discussing as they laughed at each other’s comments from across the canal.

While this neighborhood is missing amenities, it was by no means poverty stricken. I saw no raw sewage. I smelled nothing but grilled fish. And the foliage was as thick as a jungle. Palm trees, Pandanus shrubs and gargantuan bushes covered the canals in shade. We had to slow our floating to a crawl to get through the narrow passages.

However, my guide offered no guidance other than a couple of monosyllabic answers to basic questions. Even if he was fluent, I doubt he’d give me the straight scoop on the truth behind the Backwaters’ environment. It isn’t pretty. Less than half the villagers treat the water which has quietly been polluted by, among others, houseboats. Fishermen have complained to authorities that fuel, sewage and floating plastic are affecting the fish and prawn catches. Despite a state-wide sanitation campaign in 2012, the village of Chakkamkandam reportedly is engulfed with raw sewage from the neighboring temple town of Guruvayur.

But as I floated past such a serene neighborhood, I didn’t notice much civil unrest. By late morning, all of the Backwaters had awakened. Women bathed their naked children in the river. Teen-aged boys in sport shirts gawked and waved at me from the banks.

As we pulled in four hours after departing, it wasn’t even 11 a.m. yet. I sat on my porch and looked out over the tiny canal that took me on a ride I’ll never forget. In a country with more than a billion people, all screaming to be heard over this disparity of wealth, somewhere under the din is the squawk of an eagle over a rising sun.