Monti: Rome’s historical and hippest neighborhood (and once my favorite) is a slow victim of gentrification

I have searched for homes four times in Rome. I have a set routine. I call my favorite apartment search firm, Property International, and tell them to find me an affordable one bedroom in as central a location as they can find. I’ve gone all over Rome looking at apartments and Property International always finds me dreamy flats. However, never has one been available in the one neighborhood where I wanted to live the most.

Monti.

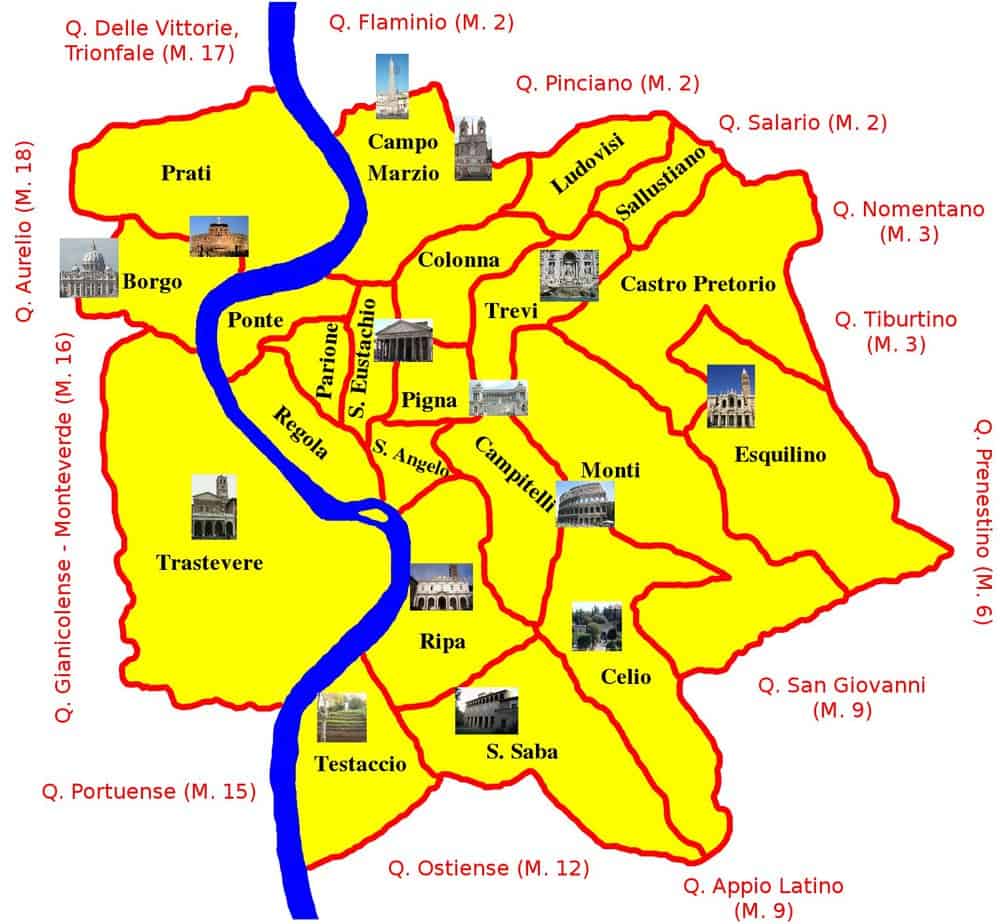

If you’ve been to Rome you were probably there and didn’t know it. It starts at the Colosseum and stretches northwest to Trajan’s Market, north to bustling Via Nazionale and the Palazzo delle Esposizioni and east through Parco del Colle Oppio. Its southern boundary goes all the way to the 4th century Basilica di San Giovanni in Laterano, Rome’s first Christian church.

Monti at its best

I love wandering Monti’s narrow cobblestone alleys and hanging out with locals around the fountain in Piazza Madonna dei Monti. I have some of Italy’s best all-natural chocolate gelato at Grezzo,

In a city that lives outside, no Rome neighborhood has the outdoor buzz as Monti. Once Ancient Rome’s ghetto, it transformed into the city’s hippest ‘hood. Businesses were booming and growing as Italy’s greatest recession since World War II crippled most everywhere else in town.

Monti is where you’ll find a Italian politician having a Spritz next to a butcher. It’s where you’ll see a UN-worthy collection of international expats drinking Guinness outside Finnegan’s. Blow off the trendy and expensive brand name stores on Via del Corso and Via Condotti and go slumming in Monti’s string of vintage clothes stores.

Big chain hotels are nowhere to be seen.

However, my favorite neighborhood has changed before my eyes. It has gentrified into just another tourist-overrun Roman neighborhood. The guidebooks caught on. Now you may hear just as much English as Italian. White fedoras are everywhere.

What Monti means to me

Too bad. I have a soft spot for Monti, like my first love I’ve grown up with as amicable friends. My retirement in Rome started here. On Jan. 11, 2014, I landed in Rome and crashed for two nights with Gretchen and Peter Bloom. Their spectacular top-floor apartment, with a view of Il Vittoriano, the massive monument of white confection in Piazza Venezia, is on Via della Madonna dei Monti. Just wide enough for one Fiat, the street once just had a couple trattories and a small market.

Michael Herzfeld, a Harvard anthropology professor who wrote a book about Rome’s gentrification in 2009 called “Evicted from Eternity: The Restructuring of Modern Rome,” says Via della Madonna dei Monti may be the oldest continuously inhabited street in the world.

To celebrate my anniversary of my arrival, every Jan. 11 I dine across the street from the Blooms at Taverna dei Fori Imperiali, the same place where they took me for my first retirement meal that night in 2014.

My favorite nightcap in the city is still Caffe Oppio, across the street from the Colosseum. Show up late at night, take an outdoor table after the tourists have left, drink an affordable glass of wine and look at Rome’s most famous monument, all backlit in all its glory. After a few cocktails, you can imagine screams across the street heard from this spot 2,000 years ago.

Finnegan’s

While I’ve never lived in Monti, I visit often. If Piazza Madonna dei Monti is the heart of Monti, Finnegan’s is the liver. It’s where I get one of the best pints of Guinness in Italy, take it outside and drink with Romanians and Americans and Mexicans and Dutch and Italians and English and Brazilians and, of course, Irish. It fills with Italians during A.S. Roma games on the many TVs inside.

It’s a hangout for tour guides and UN workers, for English teachers and English writers.

I did an excellent guided tour of historical Monti on a steaming Saturday night in the high 80s. Afterward I made a beeline for Finnegans and sucked down a couple of Guinnesses, which they conveniently make colder during the summer months.

Between chugs, I met Brent Simpson from East Lansing, Mich. He has lived off and on in Monti for five years working for the Food and Agriculture Organization. He would never live anywhere else.

“It’s not as crazy as Trastevere,” he said. “It’s not as boring as Testaccio. A lot of residential suburbs, they have their interesting little points. But in terms of a consistent four-block area, this hits the sweet spot very nicely.”

Monti is full of hip trattorias and bars with some of the best aperitivos in town. I took Brent’s recommendation and went up the street just past the Cavour Metro station to Da Silvio alla Suburra.

Around for 32 years, it’s as unpretentious as a shot of espresso and just as Italian. Just a few tables outside, it serves up some of the best Roman dishes in Monti with unpretentious prices to match. I had a new dish: tonnarelli alla Rugantino, long, round homemade noodles with bacon, tomatoes, Pecorino Romano and arugula. Fresh, light and healthy, it’s nearing La Taverna as my favorite eatery in Monti.

For a nightcap and to view the masses, I went to Piazza Madonna dei Monti. It was surprisingly subdued. In other words, it wasn’t packed elbow to elbow with cocktail and wine glasses swinging in the air. It’s a Rome weekend in July. Everyone but me seems to be at the sea.

I walked into a tiny corner bar. It had no sign. I asked the bartender the name of it.

“It has no name,” he said. “We don’t need it. It’s why we don’t advertise. It’s a local watering hole. That’s the way I want to keep it.”

Ovidiu Ghica is from Romania and has worked in Rome for 15 years. He calls the people in Monti, known for centuries as Monticiani, “radical hipsters.”

“I love Monti,” he said. “It’s alive. It has its own identity. It’s like living in a village in the center of Rome.”

He doesn’t live in the Monti for unfortunate reasons.

“If you want a rent for a year you’re going to have to sell a kidney,” he said.

Oh, what a difference 2,000 years makes.

The history

Back when Ancient Rome was the center of the world and boasted mankind’s most powerful civilization in history, Monti was Rome’s ghetto. Known as the Suburra (obviously the restaurant cleaned up the name’s image) it was teeming with gangs, violence, prostitution and graf. It was a sea of simple, single-room dwellings where the working class lived and tried to survive.

Emperor Nero used to dress in disguise and infiltrate the Suburra, trying to get a feel for how the masses were thinking about Rome – and him.

Aristocratic families in the Middle Ages cleaned up the slums by building houses and towers, some of which still dot the Monti landscape. Yes, Monti still drips with history.

About a dozen of us gathered at Caffe Roma, one of the most touristy bars in Rome, across the street from the Colosseum. Tour guide Dina Maspero took us on a two-hour tour sprinkled with interested factoids of a neighborhood that I thought I knew and didn’t:

- Why is one side of the Colosseum, the one facing Monti, better preserved with all four levels still standing, albeit with years of reconstruction? During the beginning of the Christian era in the 4th century A.D., the popes wanted the pilgrims’ procession to go from Basilica di San Giovanni in Laterano, less than a mile away, straight past this side of the Colosseum on their way to the Vatican. At least, that’s the working theory.

- The Church of Saint Peter in Chains, in Piazza di San Pietro in Vincoli, has a glass box which holds the actual chains that held Saint Peter when he was imprisoned in Jerusalem. Built in 439 A.D., the church also holds Michelangelo’s tomb of Pope Julius II. The massive floor-to-ceiling pile of white marble has Michelangelo’s huge statue of Moses. However, he built Moses with horns as Michelangelo misinterpreted Hebrew’s similar words for “horns” and “beams of light,” depicting the “radiance of the Lord.”

- Julius Caesar lived in the Monti until he was 37. The location isn’t known but he was also broke at the start of his career. His father and grandfather were from the countryside. He wanted to enter politics and found a banker, Crassus, who wanted political power and saw a young man on the rise. Caesar also made friends with a Roman noble to become accepted by the Roman elite. The rest, to say the least, is history.

- The Hotel Forum, which has one of the best views of any rooftop bar in town, used to be a convent. It still is attached to a church: Chiesa dei Santi Martiri.

- Prostitutes in the Suburra were taxed. In Ancient Rome, they weren’t just used for men’s pleasure. Mothers often took their sons to them “to be trained to love,” Dina said. Benito Mussolini also taxed the sex traders in the 1930s. It wasn’t until 1958 when brothels in Rome became illegal.

Gentrification

The Monti has changed its face many times. During the Middle Ages, the Ancient Roman aqueducts were damaged. Getting water up the hill to the neighborhood was difficult and many residents moved. Until the beginning of the 19th century it was mainly vineyards and vegetable gardens then became a popular place to live after Italian unification in 1861.

Mussolini, however, destroyed many houses from 1924-32 when he built the wide showcase Via dei Fori Imperiali which connects Il Vittoriano with the Colosseum.

By the turn of this century, however, Monti had developed in an in-place for urban, upward-mobile Romans and savvy travelers. The Blooms lived there 17 years before returning to Washington, D.C. in 2015. Peter loved the Monti so much he gave it its own article: the Monti. He called himself Il Sindaco (The Mayor). I phoned and asked how he’d describe his old ‘hood.

“When we started living there, the Monti was full of artisans,” he said. “Carpenters. Glass blowers. Woodworkers. It was just an artisan community. It wasn’t overcrowded. There was just that one restaurant (Taverna) on our street.

“The vibe was very good. People felt if they were part of the Monti, it was kind of a community neighborhood in a sense. You had these different kinds of groups and didn’t have this overwhelming number of restaurants and people. The vibe was this was a really a nice place. It was a minor, minor, minor Trastevere.

“Now it’s more like Trastevere.”

As Monti became more popular, rents went up and the artisans moved out. In came more businesses and more visitors. Herzfeld’s book reported that real estate developers and wealthier neighbors forced the evictions of many residents.

“It got more crowded,” Peter said. “The piazza when we got there had very little going on. By the time we left it was crowded all the time with young people. Places have been marked AirBnB. My building had nothing like it when I was in it. Because it was very hard to sell things in the Monti, they basically turned into AirBnBs.

“It’s like anywhere else. It gets gentrified except unlike other places, you can’t change the facade.”

Monday night Marina and I returned to the place that launched my Rome retirement. As usual, La Taverna was full for the night. It turned away customers a half hour before it opened.

Aldo Liberatore runs the place with his mom, Maria Grazia, and sister Claudia. Aldo was born and grew up in Monti, went to school here back in the ‘80s when it was more of a country village. It was dark, empty.

“When I was a child no one wanted to live here,” he said. “Just the people who were born here were proud to be from Monti. When you described it to people that you were from Monti, people would say, ‘Oh, my God.’ Now it’s different. Now when you say ‘I’m from Monti,’ it’s, “OH, MY GOD!’ It’s a sensation.”

The “great boom,” Aldo said, came in the early 2000s which was about the last time the Rome economy was also booming. That’s when they moved their restaurant to this location.

“It changed a lot,” he said. “For example this street. No one was walking before. Now look. It’s become like Via del Corso.”

I remember visiting the Blooms when I lived in Rome the first time from 2001-03. Via Madonna dei Monti was filled with locals who knew each other and old residents sitting on the cobblestones. Even at the turn of the 21st century, it felt like old Rome.

“Now there are just bed and breakfasts around,” Aldo said. “You see just people go up the buildings with luggage. They stay only one or two days. Before you saw families.”

Marina and I had a real casual dinner at Fuorinorma, one of the many takeaway street food places to appease the fast-paced crowd in recent years. I did have a terrific amatriciana panino and she had a massive cheese, vegetable and bruschetta plate. But she left Monti with a bad taste in her mouth.

In the past she has jokingly warned that if I ever move to Monti, she may find an exit plan. She’s a Roman who despises what Monti has become.

“It isn’t the Monti neighborhood anymore where there was the true Roman life,” she said. “Now it’s dirty. There’s a lot of noise and it’s really hot. Too many cheap tourists.”

I’ll keep coming back. It’ll be every Jan. 11 and anytime I’m in the mood for a good Guinness. But maybe my search for my dream Rome home is over.

July 19, 2022 @ 4:26 pm

A gem of a piece, Mr. Henderson. It stimulated my nostalgia.

My wife and I lived for two months in an excellent apartment on via Urbana. This was in 2007, from January 10th through March 20th. We enjoyed much of what the neighborhood offered, and meeting locals was easy — that my wife was fluent in Italian helped. Finnegan’s was a regular stop, and always the pub we took friends who visited us. We were in Finnegan’s on Saturday, 17 March, St. Patty’s Day, when the Irish had descended on Rome and trashed Italy in rugby. The next morning local joggers came down via Panisperna and up via Santa Maria Maggiore as part of the Rome marathon. I especially remember watching quite a few joggers step out of the race, down an espresso in the bar below our apartment, and then rejoin the race. Only in Rome! In addition, Monti was setting up to celebrate St. Joseph’s Day, a day later What a time. Your essay brought this all back.

I have been on extended stays in Rome a dozen more times, before and after 2007, but usually stay in different parts of Rome, just to live day-to-day life in different neighborhoods. (Alas, I currently prefer Trastevere.) This past February, I sauntered through the Monti rione, and indeed, even my casual visit was enough see a lot of changes. The apartment we rented more so many years ago, tripled in price. A couple casual eateries are gone, and chic boutique shops take their place. I still like the food at I Monticiani on via Panisperna, I ate there after joining in the protest march against the Russian invasion. Such a city! Already I am planning a return to the city in early 2023.

I am unhappy to read about the torturous heat smothering Italy, and the current political situation. The latter is not nothing new to Italy, but it hardly needs to happen during this time of economic and social stress.

July 19, 2022 @ 5:46 pm

Great article on Monti! I’ve walked through the neighborhood and had a meal at a place with the name Suburra a few years ago. I’m taking the train to Roma Friday and staying 3 days before flying home. I have to decide how many Caravaggios I want to cross off my list, and also plan to go back to a Santa Prassede, which I believe is in or very close to Monti. Looking at the weather forecast I will spend the afternoon hibernating! Ciao, Cristina

July 19, 2022 @ 6:53 pm

Nice writing, John, and excellent photos by Marina. Her candid scenes capture the personality of the place succinctly.

Susan and I are so glad we toured Monti last year – on your recommendation. We loved climbing the pedestrian walkways at the north end of the district and enjoyed the views framing the Colosseum in the distance.

Your article makes me want to return.

Best regards to both of you,

Scott

July 20, 2022 @ 2:07 am

By your description, I look forward to visiting Monti when Itravel to Rome in the fall.

July 20, 2022 @ 4:41 am

Love this overview of Monti, John. So interesting. We didn’t spend time there but now it’s on our screen. Outstanding photos as usually by the lovely Marina.

July 20, 2022 @ 11:55 am

As the towers of Monti will testify gentrification is not a modern socio economic phenomenon, as with the vagrancy of cheap tourists Rome has endured those shifts for thousands of years. The cultural gutting of most European cities is being driven by global forces, gentrification is a liberal term that belittles and sanitises those forces. Fear not the tower builders or the cheap tourists fear the UN bureaucrats and the overstaying cultural influencers squatting in the restaurants and sports bars of Rome.

August 16, 2022 @ 11:08 pm

G’day John, great article as always. You didn’t mention ‘Ai Tre Scalini’ which is my favourite bar in Roma. Had many a long night there with our wine tossing mate Carmelo. Great food also which is cooked off site and heated in microwaves. Been going since 1895. Mi manca tantissimo!!

Say ciao to Marina for me.

Rob