Mussolini — yes, Mussolini — to thank for Lazio’s beautiful beaches

GAETA, Italy — The golden sand stretched for miles on both sides of me. Nary a pebble pricked the bottom of my feet as I poured myself into the Tyrrhenian Sea. I waded out to my chest where I could see my feet through the translucent blue water and for dozens of meters around me. Was I just south of Rome or in French Polynesia?

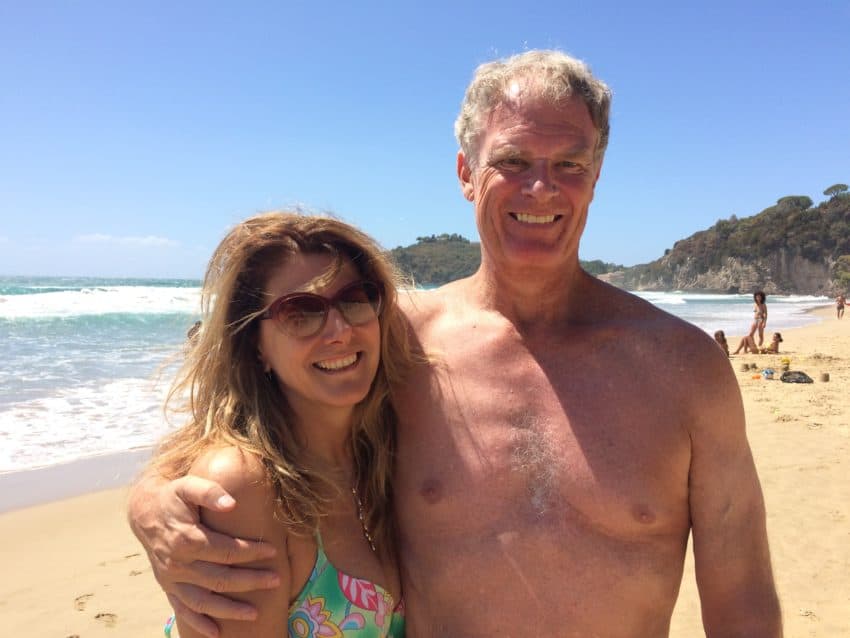

I looked back to the sand and the Riviera di Ulisse doesn’t have as many palm trees as Tahiti. It has a long row of pink geranium trees mixed with a small forest bearing the famous Gaeta olives. A small sea wall separates the beach from some tasteful, casual beach restaurants and bars where my Marina and I retired as a break from laying all day on cushioned lounge chairs under an umbrella.

Thank you, Benito Mussolini.

Rick Reilly, the best sportswriter of my generation, once advised never to write a sentence that has been written before. I’m pretty sure no one has ever written thank you to Mussolini, at least not in the last 70 years or so. Yes, he is a big reason Marina and I don’t have to board a plane or boat to relax on some of the best beaches in Europe. Our beach is 85 miles south of Rome on the Riviera di Ulisse, named for Ulysses who plied this waters during his adventures in “The Odyssey.” It’s an underrated part of the Lazio region that is sprinkled with cute towns and beaches that get more gorgeous with every kilometer you drive. Foreigners don’t come here much. Italians do. They know the convenience and pleasure of this area known as Agro Pontino, particularly now during Rome’s driest summer in the last 60 years. Where else in Europe can you get a tan and swim in a crystal-blue sea then eat a seafood feast for two with a bottle of local white wine for under 70 euros? Italians also appreciate this area for another reason.

They know in the 1930s this whole area was a swamp.

Southern Lazio was a mosquito-infested, malaria-riddled, miserable, soggy, randomly populated dump not worthy of life other than insects and Nazis. It had been like that since Ancient Rome when Caesar Augustus, whom some say was Rome’s greatest emperor, built a canal to drain the marsh and develop agriculture. But when the canals weren’t maintained during the Roman Empire’s roller coaster ride between rule and ruin, the swamps returned.

Victor Emmanuel, the first king of a united Italy, started draining the swamp in the late 19th century but didn’t finish the job. In 1928, the population in this entire region was all of 1,637 people, most of whom lived in shanties across the boggy fields. The Red Cross investigated and reported that 80 percent of the people who spent one night in the marsh developed malaria.

Imagine how cheap that beach-front property could’ve been.

Then came Mussolini. Named prime minister in 1922, he directed Alessandro Messea, the director-general of the department of health, to, pardon the expression but take this literally, “drain the swamp.” Mussolini took the plan to Parliament in 1929 and the next year cleared the scrub forest. He constructed 10,700 miles of canals and trenches, dredged the rivers, dyked the river banks, filled the holes and built pump stations. The last channel, the one that leads to the Tyrrhenian Sea, was dubbed Mussolini Canal.

Soon, cute little towns started popping up: Latina in 1932, Sabaudia in 1934, Pontinia in 1935, Aprilia in 1937 and Pomezia in 1939. Gaeta, the nearest town to Papardo’ Beach, became an important seaport.

In 1933, the project employed 124,000 people. Many were poor from the Veneto region near Venice. When the project was completed, 2,000 families were settled in two-story houses and given a farmhouse, an oven, a plough, a stable, cows and land. To this day, many people around here still speak the Venetian dialect.

What is often overlooked, however, is during the project those workers were interned in camps enclosed by barbed wire. Many developed malaria. Many quit.

And oh, yes, Benito, about your friendship with Adolf Hitler …?

Marina and I discussed this over a superb breakfast spread of chocolate-ricotta muffins, fruit and steaming, foamy cappuccino with Maria Dea, the owner of our gorgeous lodging outside Sonnino, a small town of 2,000 climbing the side of a cliff above the sea. Casale Re’ is an agriturismo homestead in a sprawling two-story white stone house with a warm swimming pool complete with a steady stream of fountains spewing water along the side. Outside our room has views of the rich agricultural fields Mussolini cleaned up and the sea beyond. Fresh grapes hang from vines next to the parking area and would later be on my breakfast plate. A restaurant is under construction behind the pool.

Maria told us official papers show the building is from the 19th century but thinks it was built 200 years before that. Casale Re’ is difficult to find. We spent way too much time crisscrossing the narrow, windy country roads that passed under bridges and ran along canals. But we curbed our frustration by marveling at the olive orchards, agricultural fields and high stacks of watermelons in the country stores. We went by factories that produce the luscious bufala mozzarella that always makes me swoon when eating it on a bed of fresh prosciutto. We’d drive along narrow roads shaded by Mediterranean pines and pass flatbed trucks with their payloads stacked with bright red tomatoes like giant cherry Jujubes. Giant rolls of grain the size of tanks (Mussolini reference entirely intended) lay side by side under a wood shelter.

From October to December, long after the sea has cooled, this area is crawling with Italians who flock here for the best olive oil in the country. With fresh produce everywhere and famous olive oil, the food here is even better than the beaches. In Pontinia for lunch, we stumbled onto an agriturismo called Pegaso 2000, a two-story red structure with potted plants lining a patio. Inside were stained-wood tables with cast-iron chandeliers and a family that has run the place for generations. The fettuccine ragu di manzo (wide pasta noodles with a tomato sauce of ground steak) beat anything I’ve ever had in Emilia-Romagna, the birthplace of ragu. The best yet is the pasta, vegetables, bread, wine and bottled water (the tap water here isn’t THAT clean still) were all of 17.50 euros.

We stepped up for dinner at Ambrosia 23 in Terracina, one of the beach towns that dot the seaside like beach balls. On a small road along the canal, we sat in dark brown wicker chairs with red and white flowers on the table and exposed stone walls. I went local, eating the spaghetti with cherry tomatoes and bufala mozzarella, a fantastic combination only made better knowing everything was made or picked within a short walk from our table.

Joined by another couple from my neighborhood in Rome, we had three seafood pasta dishes, octopus salad, grilled calamari, baccala’ (Lazio’s famous fried cod), a basket of fresh bread and a bottle of white Riflessi wine from nearby San Felice Circeo.

Of course, Mussolini never got a chance to taste the cod of his labor. He sold out Italy at the hands of Hitler and by the time he was hanging from his toes in Milan in ‘45, the Nazis had taken over this region. They stopped the pumps, opened the dikes, refilled the marshes and devastated the population. Italy had switched allegiance to the Allies and this was Germany’s version of biological warfare.

However, the major structures for water control survived and Agro Pontino, was restored. The last case of malaria, thanks also to the invention of DDT, came in the 1950s. By the year 2000, this area’s population had grown to 520,000.

Like Richard Nixon whose ties with Red China were overshadowed by the Vietnam War, Mussolini’s clean-up job in Lazio will be buried under the weight of setting back a country for years through misguided fascism.

Which means his legacy will be greater than the fascist the U.S. has now.

August 14, 2017 @ 10:05 am

Great article!

August 20, 2017 @ 7:32 am

Hi, I wish for to subscribe for this blog to obtain most recent updates, thus where can i do it please

help out.

August 20, 2017 @ 7:47 pm

Go to my website at johnhendersontravel.com. There should be a signup box. It’s free.

October 29, 2017 @ 3:00 am

John. Nice write. For what it’s worth, I lived in Gaeta for about 8 years, having left around 1986. All you state is true.

October 29, 2017 @ 3:09 pm

Thanks for the confirmation, Rich. I value your opinion more than visitors.

August 30, 2017 @ 10:15 am

Hi John,

I’m here in Rome now, arrived August 8, 2017.

This article on Gaeta I think is the best you’ve done on Italy. It’s historical and sensual at the same time! Mind blowing how you pull that off and draw us in with such ease, and with confidence! This article obviously took work and research, but all we feel is pleasure! Thanks for the respite!

BTW, I just learned yesterday that a friend back in Chicago has just released a book she wrote “Red Moon Over Gaeta” on Amazon.

San