Naples: Italy’s most chaotic city is a walk through a violent past via two tough neighborhoods

NAPLES, Italy — Italy has always been a feminine country. That’s a compliment. Its beautiful. It’s seductive. It’s warm. If you think about it, Rome’s seven hills even resemble breasts; New York’s skyscrapers resemble penises. It all fits.

So it’s natural to compare Italy’s cities with women. Milan is the snooty catwalk model, dressed for the gods with an attitude to match. Rome is the sexy showgirl. Her revealing outfit and engaging smile promises a week you’ll never forget. Florence? She loves the arts. She’s into nature. She wears comfortable shoes.

Meanwhile, Naples is Italy’s slut. Its best days are in the past but she still has a lusty air about her. She looks sweaty and tired and is scruffy around the edges. A cigarette hangs from the corner of her mouth.

Yet in a moment’s notice she can turn on the charm and be the funnest day you’ll ever have. And after a few glasses of Aglianico wine, she starts looking pretty good again.

As Naples digressed, Italy’s famous proverb for its third-largest city still holds true:

“See Naples and die.”

You can take that proverb two ways, of course. Experience the city by the bay and fade away knowing you’ve seen the best the planet has to offer. Or you can experience the city by the bay and get gunned down.

Naples’ history of violence stretches back to when it was swapped out between the Greeks, Byzantines and Normans, then when the Spanish treated it as its own public torture chamber and most recently as the Camorra crime family destroyed Naples’ rep on the silver screen.

Italians view Naples as Americans view Detroit — except Naples’ pizza is better.

However, I’ve always loved Naples like the woman it once was and still can be. I love its lustiness, its passion, its chaos.

I love how every conversation among Neapolitans sounds like they’re accusing each other of sleeping with each others’ wives. Its notorious drivers really aren’t homicidal, and the subway is clean and efficient.

They may have the most passionate soccer fans in Italy. Also, the pizza is indeed stupendous. Yeah, its bay front has lost its luster from the time when Ancient Romans built villas on what was considered the most beautiful bay in Europe.

It’s more of a bustling ferry harbor than a romantic rendezvous point these days, and Naples is short on jaw-dropping churches and museums. But it’s Italy’s most mysterious city, cloaked in a cloud of poverty and danger that puts you on edge more than any city in the country.

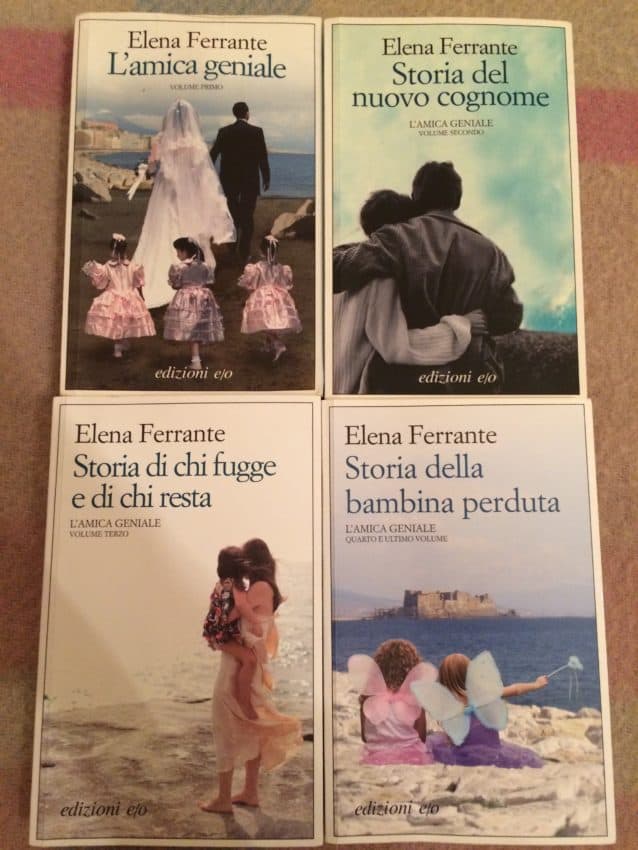

Marina, my adventurous girlfriend and photographer supreme, and I came down last weekend on the lure of the written word. Marina was reading Part IV of Elena Ferrante’s terrific four-book series about life in poverty in Naples after World War II.

I came to explore the Spanish Quarters, Naples’ most notorious neighborhood illuminated even more by Peter Robb’s exhaustive tome on the city, “Street Fight in Naples,” which I just finished.

We had both been to Naples numerous times. I remember my first trip in 2001. It was before Christmas and the churches were all decorated with presepi, the miniature nativity scenes popular all over Italy.

I walked toward one to get a closer look. The vision seemed blurred. As I approached I learned why.

The window was pockmarked with bullet holes.

Other times Naples served as a tasty connection on my way to Bay of Naples islands such as Ischia, Capri and Procida or sojourns down the Amalfi Coast to the south. I’d leave enough time to stop at Da Michele, arguably the best — and possibly first — pizzeria in all of Italy.

Naples is convenient. It’s only a 65-minute train ride from Rome, and we emerged from Stazione Centrale to searing heat. Fall has arrived in Italy and in Rome I’m wearing long-sleeve shirts for the first time in six months.

I looked at Naples’ temperature on my cell phone. It read 75 degrees. It felt like 95. Naples always feel like it’s 95.

Welcome to Italy’s third circle of hell.

We didn’t cross the River Styx. Instead we crossed Piazza Garibaldi which is much dirtier. The smell of urine hit me like descending a New York subway staircase on a hot summer night.

We walked east down Via Taddeo da Sessa, away from the crowds in Centro Storico west of the train station. We walked below Napoli Poggioreale, the prison which houses many of the Camorra crime gang who actually get convicted.

Marina was leading me to Rione Luzzatti, the teeming ghetto where Ferrante grew up. I have a perverse fascination with the soft underbelly of touristy cities. I like to peel back the layer the city doesn’t want outsiders to see, such as last year when I wrote a three-part series about Tor Bella Monaca, Rome’s most dangerous neighborhood [LINK].

Rione Luzzatti has the same feel of a neighborhood that has lost its soul. Apartment buildings with peeled paint expose bricks that look ready to fall at any moment. Pink and green walls haven’t seen a coat of paint since the Germans bombed the city.

Laundry hangs from every window sill. Holes pockmark the walls. Four potted plants with pretty flowers look so terribly out of place on a balcony, like a fashion model in prison.

Some old tired-looking women sat on folding chairs in front of shops without customers. Six youths sat on the stoop of a municipality. In the back of a church is a concrete volleyball court. Barbed wire surrounds vacant courtyards.

We saw a piazza where chubby little boys in Napoli’s sky blue soccer jerseys kicked around a soccer ball next to a truck selling panzaratti, big pieces of fried bread covered with sugar. Locals ate and gossiped in a dialect as foreign to Marina as it was to me.

“This is the true Naples,” Marina said.

We walked into a giant, beat-up courtyard between two apartment complexes. Rocks. Dead grass. Litter.

Looking again out of place was a beautiful glass display case showing the Madonna of Lourdes from 1957, surrounded by pink and yellow flowers. Nearby was a motor scooter.

“Typical Vespa,” Marina said.

We walked by another motor scooter on blocks.

“This is a typical Vespa for Naples.”

Elena Ferrante was born in 1944 and writes about Elena Greco and her friendship with Lila Cerullo growing up in Rione Luzzatti where the Camorra had a constant presence. The series follows Greco’s path to university in Pisa to become a writer. The series continues through the 2000s when the Camorra grew in strength.

Modern Naples tries to identify itself with pizza, its bay and its warm hospitality. But as much as anything it’s identified with the Camorra, Italy’s oldest organized-crime syndicate that dates back 400 years.

It became immortalized in journalist Roberto Saviano’s 2006 book “Gomorrah,” a detailed look at an organization that made a fortune on drugs and knock-off clothes and intimidated the bejesus out of anyone who stood in its path.

How does having quick-drying cement poured down your throat grab you? That’s one of the Camorra’s methods of elimination.

The book spun into a popular TV series that belies Italy’s reputation as a peaceful country. This is Naples. It’s where certain neighborhoods still kiss the muzzle of a gun and the top authority on the block does not wear a badge.

The Camorra, or, as the Neapolitan dialect refers to it, O’sistema (The System), is still alive and very well today. The Wall Street Journal reported that since the 1990s Northern Italian businesses have paid the Camorra to dump their industrial toxic waste rather than pay higher rates for safer disposal means.

The Camorra has reportedly dumped 10 million tons of industrial nuclear waste, causing cancer to rise dramatically in Naples’ outskirts, particularly among children.

From Jan. 1-Feb. 8, 2016, nine people were shot and killed in connection with the Camorra. Eight more were gunned down from May 25-June 4. Even the army marched in.

The Camorra isn’t like the Cosa Nostra in Sicily or the ‘ndrangheta in Calabria. Those are closer-knit families. The Camorra is a loose collection of gangs fighting turf wars in and around Naples. The latest trend crime officials see are baby gangs, with armed soldiers as young as 12 and bosses of 16.

Saviano, who has been under police protection ever since his book’s publication, recently told La Repubblica, the Rome-based national newspaper, “Here normal government is a daily war linked to drugs fought by combatants who are not even of age and supported by the tradition of omerta (mafia code of silence).

We must stop treating Naples like a normal city. It’s not one. Neapolitans are forced to keep their heads down because they are living under gunfire.”

From Sicily to the Alps, everyone in Italy considers Naples Italy’s most dangerous city. That’s a little misleading. Much of it is due to the Camorra’s ferocious reputation which solidifies every week on Italian televisions. However, the Camorra is not a threat to outsiders. Unless you screw them on a business deal or one of their wives, you’re going to be safe.

From a world standpoint, Naples isn’t bad. According to the Crime Index’s mid-2017 report, Naples is the 65th most dangerous city in the world, behind such places as Marseille, France, and Townsville, Australia. Naples isn’t even the most dangerous city in Italy, according to the Index. Catania, Sicily, somehow, is higher at No. 61.

Naples is, however, No. 1 in Italy in robberies, according to ISTAT, Italy’s statistical arm, and it’s in dire financial straits. It is $1.36 billion in debt and has an unemployment rate of 22.6 percent compared to Italy’s 10.7.

Unemployment among youth is 53.6 percent. Bloomberg Press compared Naples to Detroit, and you know that’s not a good sign.

Naples’ reputation for mind-bending chaos is well earned. This place makes Rome look like Geneva. Unwilling to walk back in the heat, we took a seat at a bus stop on the main road.

Behind the bench were empty Peroni beer bottles, plastic water bottles, cigarettes boxes, an old shirt. Then again, I don’t remember seeing a trash can anywhere in the neighborhood.

At this lovely garden spot we waited. And waited. And waited. The bench offered no shelter for a sun that always feels in Naples as if it’s 100 yards above you instead of 100 million miles. No buses. In one hour we saw one go the opposite direction.

Finally a car pulled up and an old man behind the wheel asked us, “Going to the train station? I’ll give you a ride for a euro each.”

I thanked the man and told him we waited an hour for a bus. He smiled and said, “When the pope passes, the bus passes.” He explained that he drives around the neighborhood and gives rides to people tired of waiting. In the back seat was a young couple: a pretty long-haired blonde with a bolt in her lower lip and a boy with a ball cap and sagging black jeans.

The four of us got out and entered Piazza Garibaldi. This has become a nerve center for African immigrants and the side streets spoking into the piazza are filled with more black faces than South Bronx.

The girl looked behind us and said, “Guarda,” and pulled down the skin below her eye with her thumb, the Italian gesture for “watch out.”

We took the beautiful Metro subway, complete with white and turquoise mosaics on the walls, to the Toledo station, the jump off point for the Spanish Quarters.

We didn’t have to ask for directions. We knew we had arrived when we saw a maze of alleys covered in laundry and banners strung across passageways so narrow that people in buildings on opposite sides could shake hands.

This is what happens when the streets are laid out 3,000 years ago by Greeks who merely needed space for horses and wheelbarrows. What the Greeks didn’t know was that today 14,000 people would be crammed into 8.6 million square feet, just a little larger than Disneyland.

Whole chickens hung by their feet in butcher shops. Red chili peppers covered a street stand. The smell of garlic and pork filled the air.

“This is like a casbah,” Marina said.

Just past a piazza we entered the maw of a huge mob waiting to get into Trattoria Da Nennella. Plates on the outdoor tables were filled with crayfish the size of lobsters and cascading baskets of fresh fruit.

“Real Neapolitan food and cheap prices,” said a woman with a Neapolitan accent waiting to get in.

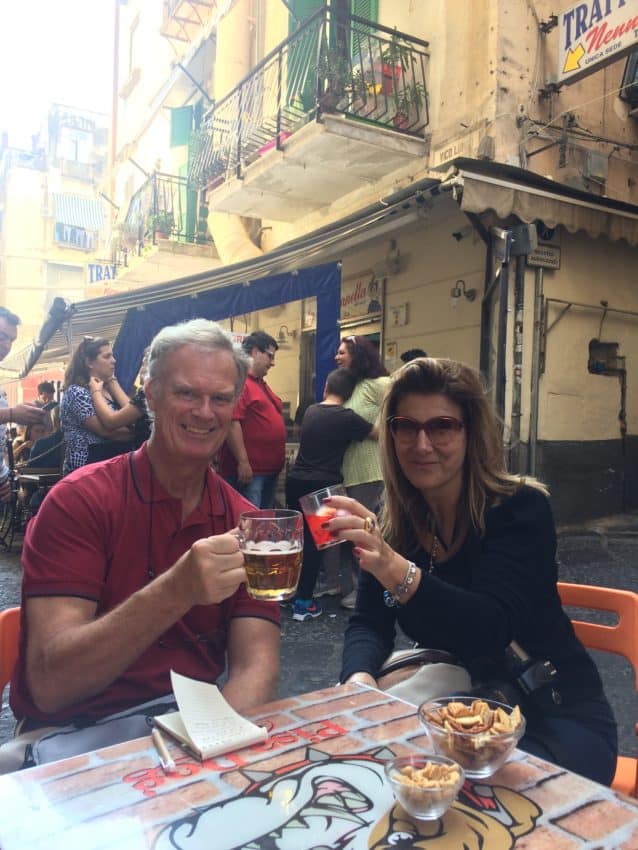

Saving ourselves for Da Michele later, we took an outdoor table at a tiny bar called Pisa Dog. Cuban music blared from inside where a youth served us up a draft beer and a bitter for all of 6 euros. We sat next to two young Frenchmen in for the big Napoli-Inter Milan soccer match that night. Naples, despite its unemployment and constant cloud of Camorra, is in a good mood. Napoli is in first place and favored by many to win only its third title in history and its first since 1990. In Italy, soccer can make you forget.

We talked about Italian soccer and American politics in brilliant sunshine with cool music, cooler drinks and a lively, happy crowd. We could’ve been in Rome’s Piazza Navona, Paris’ Montparnasse or Madrid’s Plaza Mayor.

But we were in Naples’ Spanish Quarters, a neighborhood with a history as notorious and violent as any in Europe.

It took its name from being the headquarters of the Spanish garrison when Spain ruled Naples from 1503-1860. The Spanish used this central location to help quell any Neapolitan revolts.

They wanted Naples to be its new Mediterranean metropolis but it found a run-down city with a lousy infrastructure, crowded neighborhoods lacking in water, sewage and housing.

The center of Naples was Via Toledo, still the nerve center of the Spanish Quarters. For 400 years it has represented Naples at its most chaotic. The French writer, Stendhal, visited in 1817 and called it “the most crowded and the gayest street in the universe.”

It housed the Spanish garrison for more than 300 years as they liked the location under the mulberry trees above the royal palace, the port and Castel Nuovo, the 13th century castle.

The Spanish laid out narrower parallel streets and built atop the neighborhood. Soon, the Spanish Quarters in the 16th century was arguably the most crowded neighborhood in Europe.

With the influx of foreign military personnel, the biggest industry in the Spanish Quarters became sex. Wrote Robb in “Street Fight in Naples”: “A woman from the Quarters was a prostitute unless she could show reason to believe otherwise.”

Fights often broke out between the Spanish and Neapolitans and killings were frequent. A Spanish soldier had a better chance surviving on the battlefield than in a dark alley facing a jealous Neapolitan with a sharp knife. The neighborhood became a European center for transvestite prostitution.

“Spanish Naples was a trap its inhabitants could never escape from,” Robb wrote.

In 1651, the Spanish crown had enough and moved the military’s barracks elsewhere. However, the Spanish Quarters’ reputation remains to this day and Camorra lieutenants are among the regular mob.

The Spanish would go on to abuse Naples on a level astounding even in the blood-stained history of colonization.

Besides taxing the locals to their fedoras and discouraging Neapolitans for any business initiative, Spain turned the Market Square, south of the train station, into an outdoor torture chamber during the Inquisition.

People were beheaded, burned at the stake and quartered for offending God or the king of Spain.

Spain finally relinquished control to general Giuseppe Garibaldi and the Kingdom of Italy in 1860 but the chaos remains. Even modernization hasn’t helped.

At Da Michele, we waited an hour to get in and an hour for our pizzas. A Maltese couple next to us had to flee to their waiting cruise ship before their pizzas arrived.

But like pizza, you can overdo Naples. It’s good in small doses, a wild, unpredictable night that may not be fit for a diary or blog later. Like the tired old woman who has seen better days, Naples will always hang in there, sitting on the bay, hot and sweaty and friendly.

Just don’t turn your back on her.

October 29, 2017 @ 5:59 am

I was in Naples in the early seventies and was not impressed by the tightness feeling I had and the pay to use beach. I met an acquaintance from my train adventure there . Although the writing was interesting and the pics were eye catching, Naples is not where I would go in the future.

Sent from my iPhone

>

October 29, 2017 @ 6:44 am

Great article John. It would have been very interesting to be there with you two and see that side of Naples.

October 29, 2017 @ 10:15 am

Napoli Centrale train station Cafeteria has the most delicious pizza I’ve had anywhere. And they sell it by the slice! My fave is the juicy chunk tomato and mushroom pizza! Can’t get enough of it!

October 30, 2017 @ 3:49 am

It’s the big cafeteria on the main floor. It’s been a few years. It was the only cafeteria I saw at the time. I thought their pizza was delicious, especially the chunk tomato and mushroom, so juicy and flavorful with local produce. And they sold it by the slice! I sampled every variety, but loved that chunk tomato and mushroom! And they have great “American” coffee too. The gal at the counter grabbed a huge cup and poured in whatever she had in her pot!

October 29, 2017 @ 12:56 pm

Having spent a couple days solo in Napoli in September before heading to Ischia, I really enjoyed your post reliving my passegiata down Via Toledo to Spaccanapoli its entire length and back. Although always observant, I felt safe. What struck me after 23 trips, traveling all over Italy, and having Italian roots, I felt I stood out and could easily be identified as a tourist. This was a first for me. I love the energy and chaos, and will return to spend more time there.

November 2, 2017 @ 1:17 am

On Monday night when I got lost in Balduina, a lot of good men got me to the Cornelia Metro stop where I had not been before. So I go into this big bakery next door, and in two seconds two little girls tell their parents that an Alien has landed! Now I am ALL Italian, an Italian citizen, I look Italian, and I wear Italian fashion and Italian shoes. But dang, these two little girls spotted me in a sec! So I did what any US American gal (I’m also that) would do – I ran out of the shop as fast as I could. A safe distance away, I turned around and faced my accusers, and yep, all three females were staring at me! Oh WTF! Only the mom turned her face away, and the father was trying to reason with her. You’d think I was back underground at the Napoli Cavour Metro stop!

October 29, 2017 @ 1:13 pm

Tell me how you got on the Metro John. A few years ago I lodged in District Sanità at the north end of Napoli. I never made it on the Metro at Piazza Cavour. I’d descend to the underground all times of the day and night, never made a difference. The huge crowds would jump on the outside stairs of each car as the train pulled into the station and it just kept moving with people hanging off the stairway! The cars would be empty! This repeated for every train.

So I then waited for the bus and a guy in a van would stop and offer to take us to the Cimitero for one Euro each, and back. All the ladies got in the van! I, not wanting to be left alone at the bus stop, got in too! All because I couldn’t board the Metro!

October 30, 2017 @ 3:32 am

The outside stairways leading up to each train car. People would jump up on these stairways and just hang on while the train kept moving. It never did stop to let the cars fill up. I’ve never seen anything like it anywhere. It’s hard to picture cause it’s so weird.

October 29, 2017 @ 1:27 pm

I have another interesting story about Napoli, this from several decades ago. An ancestor, a young man at the time, Italian from Lazio, got robbed in Napoli. He had no money for lodging or food and no money to return to the USA. So he sold his land in Italy that had come to him via Inheritance, changing the course of his entire family forever. He had gone to Napoli because his wife, my great aunt, was from a small town outside Napoli.

October 30, 2017 @ 3:40 am

Well you know how important ownership of property is historically in Italian culture. His family had no property to build on, so there was no traditional standing in the community and no legacy to pass on. Those who bought his property were able to divvy it up, sell it and make big money on it, and build their own homes on pieces they carved out for themselves. He would have preferred to keep his inheritance, but one bad day in Napoli changed all that.

October 30, 2017 @ 7:42 am

I find it rather misleading to identify Naples with the spanish neighborhood. It’s just like identifying New York with the Bronx.

Go to the Posillipo or Vomero hills, and you’ll see many gorgeous buildings and villas.

November 2, 2017 @ 1:31 am

Yes, very nice areas. I often read the Rick Steves Travel Forum, and readers always recommend Chiaia district and Piazza del Plebiscito as two good areas for tourist lodging. Tourists staying in adjacent/nearby areas also make good reports.

I, on the other hand, go up north to District Sanità where my B and B owners would check my appearance at the door before leaving to be sure I would not be targeted on the street. Sometimes I got sent back to my room to make adjustments. I still got noticed, but a steady stare quickly dispelled any thoughts of tampering with me. Still, it’s a hassle.

October 30, 2017 @ 5:56 pm

Hi,John — great piece — and the photos were a wonderful accompaniment (I wanted more!) The post perfectly describes the mixed feelings I had after my first experience in Naples in 2002 — and even the several hours I spent there in mid-September this year, as I made my way back to Rome from Sorrento. Unfortunately, it was a Sunday and da Michele was closed! Imagine — a restaurant closed on a Sunday? I wound up having a great pizza almost right across the street. Despite that serendipitous result, Naples was its typically crazy, chaotic, messy place.– and I will always prefer Roma! Looking forward to more about your travels. Best, Mike

November 17, 2017 @ 4:22 am

As a Neapolitan, the only suggestion I can give to foreign tourists is to dismiss opinions on Napoli from Northern Italians. They are biased and hate Napoli and the South on a personal level. Most of them have actually never been to Napoli and spend hours writing crap about it on the internet, non only on italian-language website but also on foreign ones. I suggest you only hear opinions of foreign tourists who have actually been there and can give you an unbiased opinion. Napoli had a 23% increase in tourism in the last year. So did its neighbour City Salerno. There’s no town in Europe with such a high concentration of different buildings and monuments from different ages: Greek, Roman, Norman, French, Spanish. Some towns and islands around Napoli (Capri, Procida, Amalfi, Sorrento, Ravello) are simply breath-taking and the food is to die for. Northern Italians have an interest in dragging you away from Naples, to the super-crowded centre of Florence and Venice, where you will pay gold for an espresso and where there’s really little to see OUTSIDE of the city center.

January 4, 2019 @ 6:13 am

This is one of the best articles I think I’ve ever read on Naples. Your descriptions, your analogies “Naples is the slut” were so original and captivating. I truly enjoyed this read. I came here to read one or two lines, and ended up being drawn to the entire article and your very sophisticated writing style. True journalism and amazing poetry. Thank you for this, bookmarked this website and look forward to reading some of your other articles.

April 19, 2019 @ 7:38 pm

I spent many months in Naples as a sailor in the 70s. I developed a real passion for the place, even though I was pickpocketed and swindled a few times. I was mesmerized by the Spanish Quarter and wandered the alleys often. I will go back someday. I’m a writer now and I loved the Ferrante quartet.

June 2, 2019 @ 8:11 pm

Great article!!!!!!! How did your girlfriend manage to take such great photos? I’ve always heard that you shouldn’t flash your phone or camera around in Naples for fear of being targeted.

January 2, 2022 @ 5:16 pm

Because it’s not true

January 30, 2021 @ 12:03 am

We spent 10 days in Naples in 2018, and it wasn’t enough. We found it absolutely fascinating. I’m currently doing some research on the Spanish Quarter to update my travel blog from that trip and that’s how I found your page. It was a great pleasure to read about it. The only thing I don’t agree with is the end that it’s good in small doses. I can’t wait until we can travel again so that we can go back and see all the places we missed.

If you’re curious about my take:

https://wordpress.com/view/dosvidania.wordpress.com

January 2, 2022 @ 5:19 pm

Naples has many beautiful places and have you photographed the degradation of the suburbs.

April 12, 2022 @ 12:31 pm

One of the most horrendous places I ever been. I book an Airbnb for a night after Pompey . Ever the city is already dangerous, people drive like crazy. I was arriving at my destination, pulled off rubbish all over. Looks like inception movie with all those buildings on top of me. Didn’t even arrive to my destination when I decide to turn around and never, ever! Comeback!. Horrible, mega dirty and dangerous

February 15, 2023 @ 1:47 pm

I’m Australian but my father is from Napoli and left post WWII. All his family remained but him therefore I return to visit family. Many of my cousins still live & work in Napoli. I stay with them when I visit. The city is full of passionate people, wonderful food, beautiful scenery and amazing history. It’s my favourite city in Europe. It was bizzarre seeing photos sent to me of Napoli during the early part of the pandemic with not a soul on the streets!! I was happy the Napoletano people didn’t stay off the streets for too long.

April 5, 2024 @ 2:27 pm

I hear all of you, and all of you sound like the real reason Naples is dirty. My family left there in the 1880s and your liberal elite wonder bread asses have kept it the same way for almost 150 year. Good job! Go to Venice. Or Manhattan for a fundraiser. You’re not special. If you were, you wouldn’t feel the need to visit the most dangerous city in Italy and write a blog about it.. stunads.

April 7, 2024 @ 11:43 am

You’re blaming me for Naples’ problems? That’s new.