New Year’s Eve in Morocco: A call to prayer for all mankind as Islam beckons

FEZ, Morocco — Marina has a good sense of adventure but it has limits, like a girl losing her nerve at certain roller coasters. At least, I thought it did. That ended over the summer when she made a surprise suggestion for our now annual New Year’s Eve getaway.

Morocco.

I was startled. I said, “I thought you were afraid to travel to Islamic countries.”

“No,” she said. “I was afraid to travel to Islamic countries with an American.”

Fair point.

I come from a country where hating and distrusting Muslims has become part of many Americans’ DNA. That’s thanks to a president who doesn’t ban guns but does ban six Muslim countries. That DNA isn’t in me. I’ve traveled all through Islam and have met some of the most wonderful people in my life. I went to Tunisia a year after 9-11 and had half a dozen Tunisians offer their condolences.

I thought this angle would make a good travel piece: American travels to North Africa and shows America the peaceful people of Morocco. COME STROLL THROUGH A MEDINA! LEARN SOME ARABIC! BUY A CARPET!

Then I researched.

Turns out, according to The Guardian, 1,600 Moroccans went to Iraq and Syria to join ISIS. About half were killed. Most of the others returned to Morocco once ISIS’ footprint began shrinking. Moroccans have been linked to terrorist attacks in London, Paris, Barcelona and Brussels. Abdelhak El Khayam, head of the Central Bureau of Judicial Investigation (Morocco’s FBI), claims his organization has broken up 167 terrorist cells since 2002. They’ve arrested 2,720 suspected terrorists and foiled 276 terrorist plots.

What kind of fireworks is Morocco planning for us anyway?

As it turns out, this is the lasting impression I had from five days in Morocco: I had just purchased a Christmas gift (not belated but for 2018) from a man in a long gray, hooded djellaba and was walking out of the medina, one of Morocco’s famed labyrinthian marketplaces. A man yelled at me, “MEESTER! MEESTER!” Tired of merchants trying to sell me everything from carpets to hookahs, I kept walking. He followed me. “MEESTER! MEESTER! PLEASE!” I ignored him.

I finally exited the medina and felt him grab my arm. I turned around, angry. The merchant in the gray djellaba was with him. The man who followed me said, “Sir! You paid this man 70 euros (about $85) instead of 70 dirhams (about $8). He wants to give you your money back.”

Feeling lower than Morocco’s lowest beggar, I apologized in three languages and instead of giving him 70 dirhams, I gave him 100. It should’ve been more.

Making it more remarkable is 15.5 percent of Moroccans live on $3 a day, according to the World Bank. In November, 15 people died in a stampede during a food distribution in Marrakech. Unemployment is over 10 percent and the country spent billions during the Arab Spring to calm protests over the current state.

Morocco isn’t on Donald Trump’s banned list but every American should experience what I did before judging an entire religion. It’s why I come to Islamic countries. It’s why we came to Morocco.

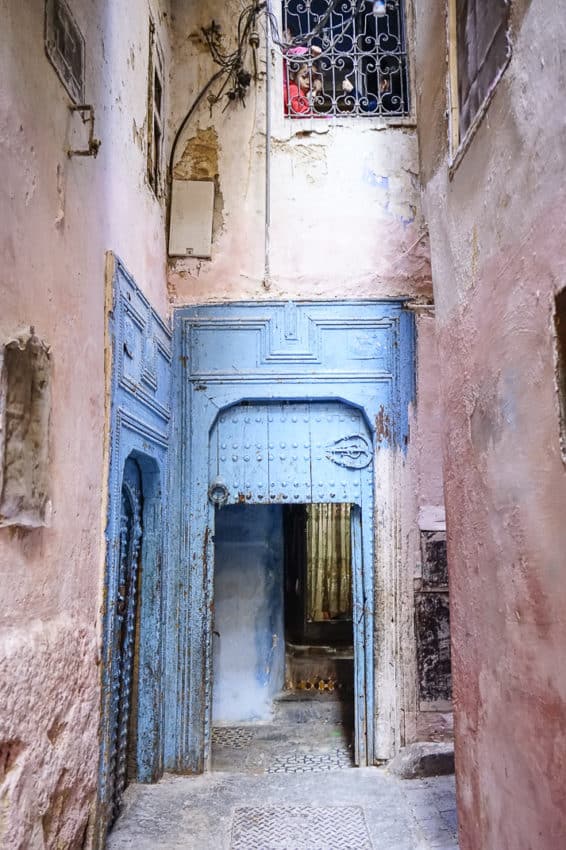

We picked Fez, not only because it’s a direct 2 ½-hour Air Arabia flight from Rome but it has the world’s largest medina. No place on earth is there a larger car-free zone than Fez’s 540-acre medina where 155,000 people live in a maze of twisty, narrow alleys that seemingly never lead to an exit.

I’d been to Fez before. Morocco was my first third world country when I backpacked around the world for a year in 1978-79. Back then, Fez’s medina was a dark, dusty, scary cauldron of aggressive touts, beggars and thieves. Locals told me don’t go in without a guide. I did but only took right-hand turns along the surrounding wall. I returned taking left-hand turns.

A renovation in the 1990s transformed the medina. Today the dust is gone and the stone pavement seems too clean to be real. It’s well lit with many wide-ranging restaurants and while the signage still makes it a confusing maze, I had no trepidation descending into its bowles without leaving a trail of rice to find my way back.

The medina is not antiseptic. It still makes you feel as if you’re in a chapter of “Arabian Nights.” We passed old men in older djellabas hunched over wobbly canes. We sampled dates and olives and almond griouats, the sugary, too-sweet-to-be-true almond treats from huge baskets sitting in front of tiny shops. Five times a day we heard the adhan, the Muslim call to prayer, scratching through a loudspeaker. I had the same feeling I had nearly 40 years earlier.

Fez is as different as any place in the world. It crushes your sense of normalcy, like a splash of ice water on a winter day. You can’t sleep in Fez. Your eyes are always open.

The medina still has the little fresh orange juice stands where small boys squeeze you a delicious glass for 30 dirhams (1 euro). The carpet shops remain a center for some of the best products of the Arab world but nothing for a budget traveler. The bargaining merchants today are only a little annoying. In other words, they follow you screaming rapidly reducing prices for only 100 meters and no longer to your hotel.

Fez is a special place to Moroccans. The name comes from the Arabic word fa’s, meaning “pickaxe.” Legend has it that Idris I, founder of the Idrisid dynasty which ruled Morocco from 788-974, used a pickax to create lines of the city when he founded Fez in the 9th century. It replaced Marrakech as the capital and remained until 1912 when the French invaded. General Hubert Lyautey, showing French snobbery isn’t a recent phenomenon, didn’t like Fez’s anti-French stance and moved the capital to Rabat.

Today, Fez remains Morocco’s spiritual and intellectual capital and home to the world’s oldest university, Al-Karaouine, founded in 859. Unesco made Fez’s medina a heritage site in 1981, meaning its foundation must be preserved.

Marina and I traveled with Paola and Saverio, a couple who live down the street from me. Neither speaks English, let alone French or Arabic. I brushed up on enough of my old Arabic to at least earn big smiles from locals if not big bargains.

We checked into the Zalagh Parc Palace, a five-star hotel with a pool that meandered around the hotel like an oasis. It was as cold as the Baltic in daily temperatures that dropped from the 60s to the 40s. A sexy bar and brilliant breakfast buffet made up for an indifferent staff, sketchy Internet and long, dark hallways that moved Marina to tell me, “This reminds me of that movie about the hotel in Colorado.”

So every time I walked to our room at the end of the hall I saw the two little twin girls from “The Shining” staring at me. Thanks.

We started our trip with a walking tour of the medina. Walking tours in strange cities can be screamingly frustrating even with GPS and Lonely Planet. In Fez’s medina, it’s like you’re a rat in a lab maze with no cheese to lure you around the right corners. I told myself to revel in the mindless meandering. That’s good because we were lost in 10 minutes.

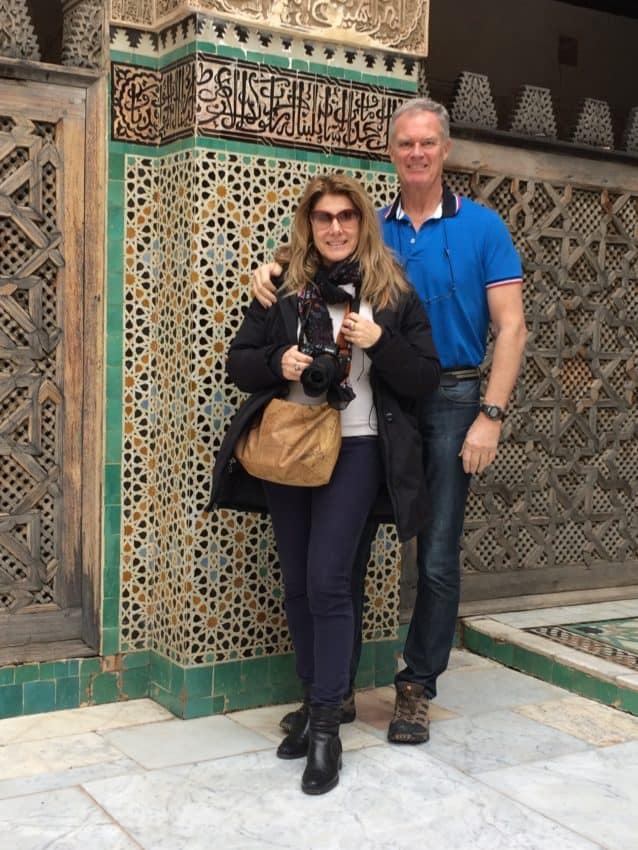

We did find our way to Bou Inania Madrasa, built from 1350-57 and one of Morocco’s top schools for the Koran. We walked inside a large square lined with beautiful hand-carved walls. I walked by a small side room where a young man in a green skull cap knealed, facing east, muttering a prayer in Arabic.

Fez is a deeply religious city of 1 million people. While covering their heads isn’t required as in Iran and Saudi Arabia, many Moroccan women choose to do so. Some even wear the full burqa by choice. I arrived bound to respect Fez’s customs favoring modesty. I temporary lost my mind when I leaned over and kissed Marina, wearing comfortable shoes and red cords.

Then I heard a male voice. Oh, no! I’ve been kiss caught.

“NO PROBLEM!” yelled a young man loud enough to ring down the street. “GOOD! KEEP KISSING! IT’S GOOD TO SEE A MAN KISS HIS WIFE!” He came over and shook my hand. Maybe he was jealous. Then again, maybe he was just friendly. In other words, maybe he was just an average Moroccan.

Parts of the medina are a bit of a tourist trap. I saw very few Americans but many French who can communicate with the bilingual population. I veered us to one of the medina’s biggest drawing cards. The Cafe Clock has been around only 11 years but it has evolved into a must on the Fez to-do list. Located down two narrow alleys past walls of brilliant artwork, Cafe Clock is a five-story restaurant with a narrow staircase leading to a rooftop view of the medina. The bottom floor where we found a table had a very French feel with a skylight illuminating us all.

I ignored the total lack of Moroccan customers and ordered the signature dish: the camel burger. I’ve eaten strange animals before: zebra and hartebeest in Kenya, rat and dog in China, yak in Nepal. But this camel burger beats them all. It had little fat and was a little sweet, like the buffalo I often ate in Colorado. It’s made even better sandwiched between two pieces of fresh, homemade bread found all over the medina. And yes, the waiter assured me, Moroccans do eat camel.

Walk through the medina for just 10 minutes and even non shoppers get itchy wallets. I’m one of the few men who likes to shop. Thus, to me, Fez’s medina is like a meth lab to a junkie. I Christmas shop all year round. I buy something in every country I’m in. By the time the third week of December rolls around, people are frantically power shopping while I’m standing on my terrace drinking a glass of Montepulciano and listening to Bing Crosby Christmas carols.

In Fez, I got a third of my family Christmas shopping done 51 weeks ahead of time. I could’ve done more but I doubt pointy Ali Baba shoes go over well in Eugene, Oregon. The medina’s sidewalks are lined with everything to decorate your home, from your living room to your bathroom to your closet. Hard scents of musk and lavender. Body oils made from olive trees all over northern Morocco. Oil paintings of everything from Berber nomads to veiled women. Ceramic shops filled with multi-colored dining and tea sets. Long-elegant kaftans in every color of the rainbow. Leather coats and belts and bags. Elaborately decorated jewelry boxes big enough to store a family fortune.

The smells of leather and musk and olive oil and fresh bread fill the air and make me want to shop, eat and bathe all at the same time.

Shopping in Fez, however, requires skill. Price tags are merely for decoration. Bargaining isn’t just accepted, it’s expected. I’m a very good bargainer. It comes from my past as a budget backpacker where I counted every penny. Every lower price meant another night on the road. I was ruthless.

I still am.

One rule in Fez: You can not insult a Moroccan with your price. It’s impossible. The more they feint pain, the more they cry, the more they respect you. I always offer a quarter of the price tag. In the ‘70s, they said, “That’s a donkey price.” Last weekend when I bargained for a painting, the young merchant said, “That’s a Berber price,” proof of the discrimination this minority suffers in this part of Morocco.

The rules are simple. Find something you like and pretend you don’t. Offer a price one quarter of what’s listed and wait for the merchant’s theatrics to meld into a counter offer. Stick to your guns. Wait for him to lower. He’ll be down to half price in no time. Go up a bit to show respect. If he doesn’t match it, walk out. He’ll chase you down with your price and pretend he didn’t really make 80 percent on the deal.

Marina didn’t have a clue. She’d jump up and down, gasp and pull something off a shelf and ask the merchant, “How much?”

“MARINA!” I’d gasp as the merchant’s smile grew into a smirk.

She learned the rules and Paola and Saverio were old pros. I left with a ceramic bowl for my parmesan, a belt and an orange painting of two camels in front of a yellow sunset. The others came away with oils, tile house numbers, bags, coasters. No problem if your luggage doesn’t have room.

Just a buy another bag in the medina.

But what makes Morocco special are the people. In 1978 I met numerous Moroccans who studied abroad and returned home with college degrees to help their country. On New Year’s Eve day we took a road trip to Sefrou. It’s a city of 80,000 people 20 miles south of Fez. It’s known for its historical Jewish population and annual cherry festival, not to mention terrific views of the snow-capped Atlas Mountains in the distance.

Sefrou’s medina is Fez light. It’s for locals only, where you can feed your family but not buy it Christmas presents. We wandered the alleys as the only Westerners and emerged hungry, having no tips on where to eat. A man selling scarves off a wooden table in the street pointed us up the road where we found a hole in the wall that won’t make any guidebooks.

It was Morocco out of central casting. An old man worked a grill behind a musky window showing diced rows of chicken, lamb and beef. The smells of grilled meats waifed through onto the broken sidewalk. Smoke filled the inside of the open-air restaurant, reminding me more of a boxing gym in Vegas than a dining spot on vacation. A woman in the back ladled huge pots of rice and soup filled with chunky vegetables and beans.

We took four plastic chairs and the food kept coming. Lamb kabobs. Beans. Soups. Rice. All were washed down with sweet mint tea. Soon a man with a prescribed limp, short, grayish hair and missing most of his upper front teeth came to our table. Usually the rule on the road is if a local approaches you, he wants something. If you want to meet locals, you approach them.

Zakaria Naccri was different. He spoke very good English after only three years of university many years ago. He said his father fought with the French against the Nazis in Southern Italy at the end of World War II and in Indochina in 1954. He’s still alive, an old man with diabetes at home in Sefrou.

Naccri, 52, spoke whimsically of French occupation. He contracted polio at age 2 before the French eradicated it from the country. When a flash flood nearly buried Sefrou in 1950, the French dug the river deeper and built a bridge. The town had 25 hotels. Today there are only four.

“Jewish. French. Berbers. Arabs,” Naccri said. “There was tolerance. The French bought the Berbers land and animals. When the French left, it all went back to the Arabs.

“I like Jewish. French. Arabs. Berbers. I like all people.”

“So you’re not Donald Trump?” I asked.

“Ha! NOOOOOO!”

He led us back to the taxi stand, along the way pointing out a 99-year-old man still working, selling wicker brooms and looking surprisingly healthy. We had some of the best tea of our lives in a sprawling cafe where men watched a Moroccan league soccer game and Bob Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind” played on a loudspeaker.

When we parted, we collected about $5 worth of dirhams, promising we’d look him up if we ever returned. This time I meant it.

One reason we chose Morocco for New Year’s Eve is Marina and I don’t like New Year’s Eve. We wanted to avoid Rome on the one night of the year Romans get drunk. They have this nearly Pavlovian response to rare hammerings by throwing empty beer bottles. In Fez, few places sell alcohol. Drunks would be non-existent.

While Moroccans don’t drink much, they have learned the fine Western art of price gouging. Most of the restaurants I called from Rome had fixed prices of 75-80 euros a person. I was tempted to tell them I thought anal sex was a sin in Islam but I merely hung up. I had some restaurant recommendations in the medina but Marina wanted nothing to do with the medina at night. I tried to reassure her.

“The medina is safe,” I said, acting like an American. “There aren’t any guns.”

She steadfastly refused. So I went to the front desk to get my confirmation.

“The medina is safe at night, isn’t it?” I asked.

“No,” the desk clerk said quickly.

“Huh? Why? What happens?”

“Everything. Don’t go after 6 p.m.”

We called around town and found one restaurant with its normal menu. Zagora is in Fez’s new town, just west of the medina and where you find supermarkets and retail stores. We passed crude, neon-lit nightclubs with pulsating music already at 9 p.m. Zagora was set back from the street and lit up in red neon. I felt like I was entering a brothel. I might still have. It was empty. Not another table was occupied — on New Year’s Eve.

We tentatively took our seats and my fears faded when I saw the menu. Ever play the parlor game: What meal do you order the night before you’re executed? Mine was on the menu.

Pastilla.

It’s a dish made of chicken, egg, cinnamon and almond surrounded by filo dough and covered in powdered sugar. I fell in love with it in Moroccan restaurants in the U.S. but in Morocco it’s usually reserved for special feasts. Zagora had it and it was as good as I’ve ever had. We ate in front of bored waiters and a concerned owner who no doubt wonders if price gouging is the way to attract Western travelers on New Year’s Eve.

We repaired back to the safe sanctity of the hotel bar where a group of 10 Berbers in green djellabas played scratchy music that made me want to take a souvenir dagger and dig out my eardrums. I heard this music once before and it’s tolerable in a Tunisian desert — off in the distance. In a hotel bar right out of “Casablanca,” we had to take refuge in a ballroom with dance music.

Still, every American should visit one Muslim country. If they had, we never would’ve invaded Iraq. Think about it. No ISIS. No Donald Trump. No fear. A new year dawns. Too bad more Americans aren’t chased down by Moroccan shop keepers.