Nottingham: Vibrant, young and hopping, England’s legendary East Midlands city

NOTTINGHAM, England — I barely had time to scout the long array of spigots behind the crowded bar when the woman approached me. Maybe late 30s, early 40s with a big head of curly hair and a bulky sweater to ward off a cold English evening, she leaned into me to be heard over the din.

“Do you know you look suspicious?” she said.

Suspicious? I thought I looked typically English. I wore a gray trench coat and a black Ben Hogan hat with a stylish scarf. My heritage is one-quarter English. I could’ve passed for a prof from one of the many universities in town or just another local in for a pint. Maybe my silver notepad gave me away.

“What are you writing?” she asked accusingly.

“I’m a travel writer,” I said, more interested in talking to locals than protecting my journalistic confidentiality. “I’m here to write about Nottingham.”

“Let me see?” she said, nearly pressing her nose into my opened pages. Having no more ability to read my fractured shorthand than she could the wall of an Egyptian tomb, she shook her head and returned to her table full of friends.

This isn’t your fairy tale Nottingham. Far removed from the medieval legend that made this mid-sized English city world famous is a rollicking party scene fueled by more than 60,000 university students. A young professional population and immaculate streets give this former home of Lord Byron an air of an up-and-coming civic success story. It boasts Great Britain’s seventh largest economy despite a population of only 330,000. Weekend nights in Nottingham reminded me of all-campus parties back at Oregon — except the women here dress to the nines.

Loud youths parading up streets arm in arm. Women in short skirts and stilettos bouncing from bar to bar. No hoodies or Nikes in this group.

I had a couple assignments in England last month and decided to visit this town I’d heard so much about. It’s not just the legend of Robin Hood, whose legitimacy remains debatable. It’s not just the strong soccer culture, which has face planted since its salad days in the ‘70s and ‘80s. It’s not even the allure of what an English bartender in my favorite Rome pub called, “The most beautiful women in the UK.”

I came to see a small, bustling English city that is so much more vibrant than the rich history that Hollywood and children’s books made famous. I’d never been to the East Midlands, a forest-laden swath of land sprinkled with stately homes and green valleys in the middle of England.

Also, how can I pass up having a beer in the oldest pub in England dating to 1189? Maybe a thirsty Robin Hood and I have something in common.

The arrival

Trains in Great Britain are outrageously expensive. Ever since they privatized the railroads in 1994, the romance of English rail travel has died and been replaced with sticker shock. Nottingham is 130 miles north of London. It’s a 90-minute train ride. The average priced one-way ticket is 48 pounds (about $65). I flew from Rome to London for less.

Somehow I found an afternoon departure for only 24 pounds ($32) and pulled into Nottingham at 4 p.m. right about the time when the mid-fall sun began setting in Central England. It was a Saturday and the curvy street up the hill from the 173-year-old train station was already getting crowded with revelers.

I weaved through well-dressed partiers and checked into my Ibis Hotel. I guess it’s a sign of a fun town when the hotel front desk doubles as a bar. A group of young, beautiful Asian woman dressed for the sexiest nightclubs in town stood in the lobby. Some scruffy young Brits walked in. A woman asked, “What are you doing here?”

“We heard you’d be here,” he said with a smile and was rewarded with a gaggle of giggles.

I leaned into the hotel clerk after he gave me my key.

“What’s going on in town tonight?” I asked. “Anything special?”

“No,” he said, curious with the question. “It’s Saturday night in Nottingham.”

I took the elevator up with a woman carrying a balloon with “40th” on it and her two friends.

“You turn 40 today?” I asked.

“Ah, I remember then,” her friend said. “A long time ago: 15 years.”

“I beat you by 10,” I said.

The women laughed, maybe sympathetically, and ran to their room to freshen up for a very long night. I threw down my bag and joined the throng outside.

The Ibis is on Fletcher Gate which runs into Warser Gate, Carlton Street and Bottle Lane to form a confluence of pubs and bars that wouldn’t look out of place in New Orleans. By 7 p.m. the zone was crawling with young men and women. Lots of leather and heels. Lots of jeans and swagger.

I stopped at the 6 Barrel Drafthouse, crowded already but no one waited long for a pint with the fast, deft hands of a veteran bar staff. I asked the tall, beautiful blonde bartender about Nottingham’s surprising bar scene.

“We have the most independent businesses in the country outside London,” she said.

“How’s business been since Covid?”

“It’s coming back.”

That’s obvious. What’s also obvious is that bars like this are petri dishes for Covid. When I arrived in London the day before I’d read that the number of new cases in the UK were up to 50,000 a day. Boris Johnson, the UK’s mop-headed court jester of a prime minister, did not lay down a mask mandate. I don’t recall seeing any masks anywhere in Nottingham after departing the train.

“Yes, it’s scary,” the barmaid said.

I walked a couple doors down and took my hotel clerk’s recommendation. The Hockley Arts Club is a two-level cave-like bar with a nightclub with cover charge on the ground floor and a packed bar for free on top. I walked in and waded through the bodies and dim lighting from the Tiffany lamps hanging from above. The bartender refused to take my cash for my pint.

“Only credit cards,” he said. “Covid.”

Funny, the Brits are afraid to pass germs by cash but via mouth they’re OK. They sold Peroni, the Budweiser of Italy, for 6.50 pounds ($8.70 ) a pint. I told the bartender I can buy that at my corner bar in Rome for 2 euros.

“It’s one of the most popular beers we sell,” he said.

A beautiful middle-aged blonde in tight blue pants and stilettos gyrated alone near me. Others nearby bobbed and weaved to a long set of rap music on the loudspeaker.

I didn’t last long. I’m not a music guy. I like to drink. I like to talk. And I like to laugh. Screaming over rap music chased me out into the streets where lines were forming outside every club. I walked down the hill to Old Market Square, a sprawling open space with the gargantuan Council House and its 200-foot-high dome.

The place was lousy with cops. Many of them had dogs on leashes. I asked a cop and his female partner what happened. Nothing, they said. They brought their drug-scenting dogs for a whiff.

“If you’re taking cocaine,” the woman said, “they can tell.”

One apparent problem here is date rape. A story in the Nottingham Post chronicled a series of anecdotes of men injected women with a date rape drug in crowded bars and streets. Women spoke of waking up in strange places and not remembering how they got there.

As I roamed the loud streets looking for a place to eat late, I passed one pub with a sign reading, “STUDENTS WELCOME BACK TO NOTTINGHAM.”

The pub

Nottingham’s drinking culture dates back to practically the advent of drinking. It started with the Crusades. In fact, I had a few beers in the same bar as some of the old Crusaders. Ye Olde Trip to Jerusalem proclaims itself as the oldest pub in England. Dating back to 1189, it is named for one of the Crusaders’ destinations. This pub, built into the cliff below the Nottingham Castle, is where King Richard’s troops gathered and, um, hydrated before pillaging Israel.

The building dates back to 1086 when it was a cellar and jail for the castle. The cave-like interior and suit of armor made me want to order some skrog and call the waitress a scullery wench. Soft leather wraparound benches and courtyard seating gives it a modern touch.

The bartender, Karl Gibson, a burly man with an enthusiastic, historical voice of authority, said this area was once an open cave and the pub was built inside it. Fresh spring water was found here and it was healthier than the castle’s water at the time. It was used to make the first ale.

Karl quietly motioned me to follow him. He took me to a “Staff Only” cellar where numerous beer kegs were attached to taps on the wall. This is where prisoners were held before being sent to execution outside the castle — if they were lucky. The worst criminals got life. They were thrown in this cell with hoods and fed just enough to keep them alive, forever. Sitting in the dark with hands in irons and a stomach slowly crumbling for the rest of your eternity, maybe a beheading would be like a breather.

After a couple pints of Nottingham Brewery EPA and some lovely non-greasy fish ‘n chips, I asked the learned bartender about Robin Hood. Everyone in Nottingham has an opinion on whether he existed or he didn’t. In other words, in Nottingham, Robin Hood is kind of like God. The bartender is a non-believer.

“Robin Hood didn’t exist,” Karl said. “There are records of people in 400 B.C. There is nothing from a hero from the 12th century?”

The legend

Did I sit in the same room as Robin Hood? It depends on your grasp of romantic legends and if happy endings equate history. Talk to locals and read the history and the number of stories of Robin Hood are in double digits. The difficulty in nailing down the truth is that Robin Hood was a common name in 12th century England.

The most believable story is he came from the countryside to join the Crusades. When he returned to England, he learned the Sheriff of Nottingham had taken his land. The sheriff joined forces with Prince John to undermine King Richard, a confidant of Robin Hood but who didn’t hang out in Nottingham much.

Robin, obviously pissed off, gathered forces, known later as his Merry Men, and used the Sherwood Forest as his base. He would make forays around the region called Nottinghamshire, robbing the rich and giving to the poor. When he wasn’t fleecing strangers, he was hiding by a huge oak tree.

The tree, christened the Major Oak, still exists. It’s 800 years old and counting, and Sherwood Forest remains. It’s a 182-hectare national nature reserve about 20 miles north of town. It’s a major beehive of mountain bikers, hikers and day trippers. Every August, Nottingham holds a Robin Hood Festival complete with medieval reenactments. Robin Hood Live, another medieval celebration, is held every year for two days and the Robin Hood Beer & Cider Festival is a four-day slog featuring 1,000 beers and 250 alcoholic ciders.

Hmm. Maybe this legend is worth believing.

The castle

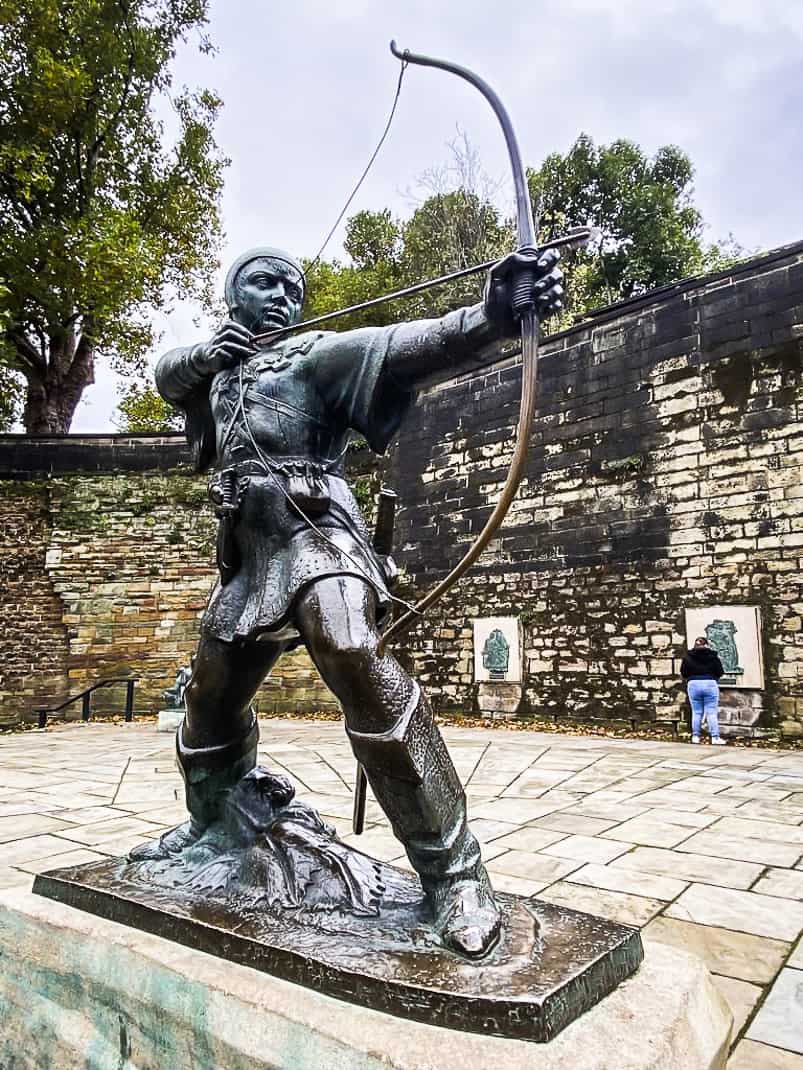

What is more believable is Nottingham’s rich history. It can all be found in the Nottingham Castle, a sprawling complex atop a cliff called Castle Rock on the southwest end of town. Built in 1068 by William the Conqueror, it’s a bit disappointing as castles go. It’s more of a square complex than a towering, forebording structure with turrets and towers. From the pub, I walked past the famous Robin Hood statue of the steel-eyed hero shooting an arrow at a distant rotter. I turned onto the castle grounds and walked through a large brick archway to a modern ticket booth and gift shop. Beyond were a huge stone building that once served as the royalty’s quarters.

What I saw inside instead was a market of vintage clothes and a photo gallery, including an odd piece featuring John Lennon’s nose. It took a large leap of faith for me to imagine King Henry V walking these halls, let alone Robin Hood.

The castle’s highlight, however, is the Rebellious Gallery. Added in June, it’s a beautifully designed, chronological account of Nottingham’s history of protest. It starts in 1330 with Edward III staging a coup at the castle. It continues on through the British Civil War from 1642-51 and the burning of the castle in 1831.

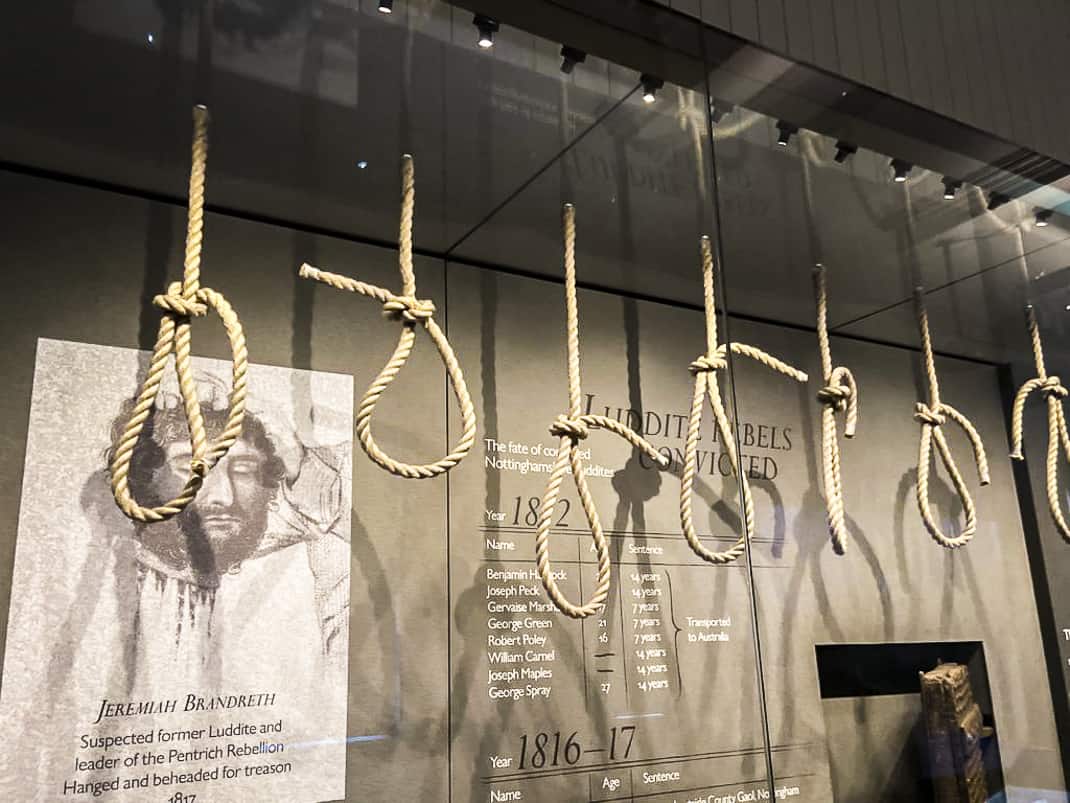

It has videos of reenactments of rioters torching the castle to protest the Duke of Newcastle’s opposition to the Reform Bill. It talks about the Luddites, textile workers who followed the lead of one Ned Ludd who led a rebellion of weavers against creeping industrialization in 1811.

There are hangman’s nooses, period costumes, staged interviews of oppressed laborers bitching about the government. There are interactive games for children.

National Justice Museum

Nottingham doesn’t just have interactive games for children. They have them for adults, too. It’s how I wound up facing a wigged judge accusing me of inciting a riot and threatening me with the death penalty.

Nottingham’s National Justice Museum isn’t your usual collection of rooms with faded black-and-white photos of criminals and a few weapons. They take unsuspecting visitors who enter the sprawling complex that once held the city’s jail and have them take part in a mock trial.

Using the same format as in the 19th century, they hauled individuals from the audience to a standing post in the middle of the authentic courtroom. An actress playing the barrister for the prosecution reads the charge while a protestor shouts support for the soon-to-be condemned.

When the barrister called my name, I protested.

“I’m an American!” I said.

“Oh! From the colony!” the barrister said. “Get up there! You’re looking shifty!”

I sheepishly walked to the dock. The audience began booing. “Hang him!” a couple of them said.

I was playing the role of one George Beck, a real criminal who did incite a riot and burned down a textile mill where 27 people died in 1831. He was one of five who went on trial in March 1832.

The judge asked me my occupation.

“No employment, your honor,” I said.

“Hard life, huh?” he said mockingly.

The trial lasted about as long as I could come up with another quirky retort, which is actually how long most of the trials lasted back then. The judge raised his feathered pen and asked the crowd, “By a show of hands, guilty?” Nearly every hand went up.

“Hey! That’s my wife!” I said pointing to a woman in the crowd before pointing to another and saying, “And that’s my mistress!”

It drew a couple laughs. What isn’t funny is what happened in real life. The day after Beck was found guilty, he was taken outside and hanged.

The museum doesn’t stop there. It also does a hanging reenactment. Well, not really. But a comic executioner in period costume does a mock hanging, ordering a visitor from the audience up to an actual gallows built in the prison yard. The executioner loudly announced to the crowd that a petition had been distributed to stay the man’s execution.

He looked at the paper and said to the doomed man, “Your own family didn’t sign the petition. I don’t like your chances.”

Soon, the barrister appeared and announces a royal pardon. In reality, they hanged criminals at Gallows Hill just outside the city center and some on the front steps of this building, the last of which occurred in 1864. The museum was once a honeycomb of jail cells which we all walked through, ducking our heads in the tight enclosures. We passed wooden stocks where prisoners’ feet were held in place and they were targets of trash, old fruit and dung or whatever the public could find. The length of the prison yard is lined with photos and descriptions of some of those criminals executed.

I later returned to the courtroom and saw the actress. Christy Fearn is a lifetime theater actress who has worked around Europe and found “her dream job” in an audition at the museum eight years ago. She’s also a Nottingham native and later I asked her by email what she likes about her city.

“In Nottingham, we have a local accent and dialect that is virtually impossible to imitate correctly and we eat chips (not ‘fries’ – we never call them that) with mushy peas,” she wrote. “We also have a castle that visitors say isn’t a castle and a local hero (Robin Hood) who may not have existed. But we shouldn’t get mardy. We should be proud of our history, not least because we are home of the original Luddites and the poet Lord Byron.”

Frankly, I don’t care if Robin Hood existed. I’m glad Nottingham does. It’s England at its historic best with a youthful twist. Nottingham rocks to its own guitar player and isn’t above a good riot.

Now if you’ll excuse me, I must go get hanged.

If you want to go …

How to get there: Trains leave hourly from London’s St. Pancras International station. The 1 hour, 45-minute ride starts at 47.48 euros but goes up to 83.10 on certain times. Bus is cheaper. They leave about every hour from London’s Victoria Station. The 3-hour, 15-minute ride is 21.12 euros. Important: Book at least a day in advance online. The prices jump when purchased on day of departure.

Where to stay: Hotel Ibis Nottingham Centre, 16 Fletcher Gate, 44-115-985-3600, Ibis Nottingham Centre, H6160@accor.com. Perfect location, walking distance from train station and in heart of city. I paid a little under 100 euros a night, not including breakfast.

Where to eat: The Cross Keys, 15 Byard Lane, 44-115-941-7898, The Cross Keys, crosskeysnottingham.co.uk. 11:30 a.m.-1 a.m. Friday-Saturday, 11:30 a.m.-10 p.m. Sunday, 11:30 a.m.-11 p.m. Monday-Wednesday, 11:30a.m.-11:30 p.m. Thursday. Quintessential English pub almost next door to the Ibis. Traditional English fare with sandwiches starting at 4.95 pounds and mains at 10.95. Try the beef bourguignon. Try the homemade faggots if you dare. (Relax. They’re meatballs with bits of liver inside).

When to go: Nottingham is rarely hot. July is its warmest when temperatures reach 71 and lows 55. Coldest is January when temperatures range from 35-45. It’s also the rainiest month. I visited in October when it was 46-58.

For more information: Tourist office, 1-4 Smiley Road, 44-0844-477-5678, www.visit-nottinghamshire.co.uk, 10 a.m.-3 p.m. Wednesday-Saturday.

November 28, 2021 @ 12:54 am

A kind of post-industrial tourism experience in UK city centres, plastic-fantastic campus vibes replacing the old town square localism, not the take it or leave it of Disneyfication or gentrification but immersion in a hard core neo-liberal cityscape.

November 28, 2021 @ 12:31 pm

Hi John

This is so interesting. I didn’t know you were in England! I have never been to Nottingham, nor does it have much of a reputation to us here down in London as somewhere to go to. But I am grateful you did it for me. Interestingly, about ten years ago it had the reputation for being the most dangerous city to live in, with the highest gun crime statistics. I am so glad to read this and hear that there is more to this city than I thought.

November 29, 2021 @ 7:34 pm

Welcome to my city!!

August 4, 2023 @ 9:55 am

The vibrant and youthful energy of Nottingham shines through in your description, and it’s evident that the city has a lot to offer in terms of nightlife and social gatherings. Your outfit seemed perfect for blending in, but the unexpected accusation of looking “suspicious” added a humorous twist to the story.

August 10, 2023 @ 8:24 am

Thanks, Paula. You familiar with Nottingham?