Owning a winery in Italy not as easy as toast but this couple is toasting now in the land of St. Francis

TODI, Italy — So you want to have a winery in Italy, huh?

Sit on your porch looking out at your vineyard on the hill, sipping the fruits of your labor under a warm sun, a plate of pasta in front of you as the church bells peal from a nearby village?

Getting thirsty? Getting antsy? Getting dreamy?

Here’s one reality.

You’re in sleeping bags on the floor of an 800-year-old stone house with no electricity, heat or water. It takes you seven years to get a building permit. You realize that your land really isn’t your land. You have no money and take equipment from cartoonish strangers on the promise you’ll pay them later. How?

Who knows?

Yet there’s another reality about the wine making business in Italy.

“With little money and just lots of work, you struggle but you know what? The truth is, we didn’t start off with this dream. We started off with an idea. That has turned into, honestly, a dream life.”

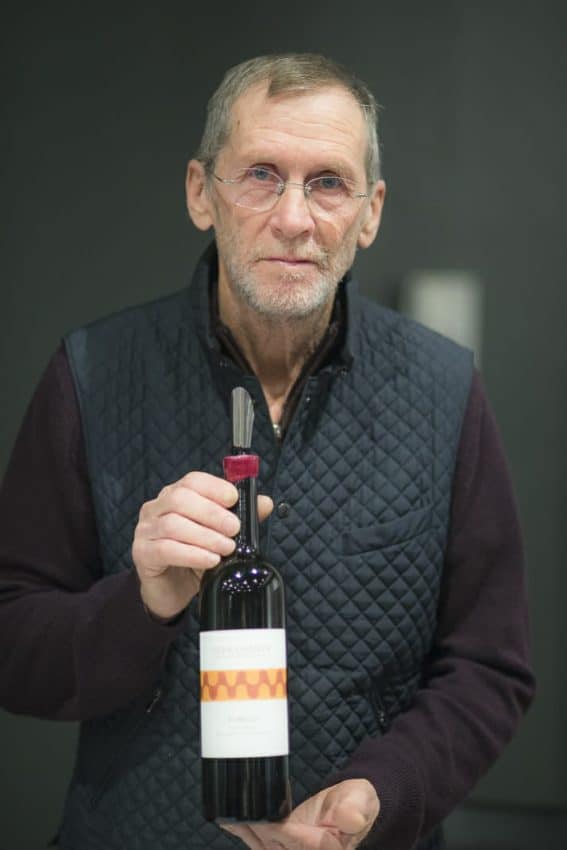

This sage advice comes from one Ev Thomas, a 69-year-old American artist who indeed is living the dream of many bored, overworked Americans with a fine taste for wine. We’re sitting in the living room of his stone house built in 1272, around the time Marco Polo set sail for China and St. Francis of nearby Assisi ditched his penthouse for prayers. The wood fire in the cast-iron fireplace warms the stone house like a dozy bathrobe against the 40-degree temperature outside.

Art is everywhere. Thomas’ paintings of the sea and a set of stairs hang on the walls. In the dining room is a table that once belonged to a family of Raphael art collectors from the 16th century.

“You’ll have lunch — and breakfast, what the heck? — where Raphael probably ate at this table,” Thomas tells me.

I met Thomas and his Sicilian wife, Claudia Rizza, at the Sangiovese Purosangue wine tasting event in Rome’s Radisson Blu hotel last weekend. They stood out in a room filled with dozens of wineries for two reasons: one, he’s an American; two, their Terramante winery is in Umbria. Sangiovese is a delicate grape that’s the main ingredient of such Italian wines as Chianti, Brunello and Montepulciano. All are prominent in Tuscany, the brightest star in Italy’s wine constellation.

I’ve always called Umbria, just to the south of Tuscany, as Tuscany Light. It has all the things Tuscany has (wineries, walled hill towns, lousy soccer) as its northern neighbor but with a fraction of the tourists and lower prices. Umbria is the only one of Italy’s 21 regions that does not border a sea or another country. Of all the regions with histories stretching back millenniums, Umbria may be the least influenced by outsiders.

The biggest influence remains a humble saint.

Francis Bernardone, better known as St. Francis of Assisi, was a wealthy, carousing son of a rich cloth merchant and a French noblewoman. After a year in prison and a bad illness, Francis went into the army in 1205 but a holy vision changed his life forever. He tossed away his gold, grabbed a robe and spent his life helping the poor and living in a cave.

Now enter Ev and Claudia, living in what amounted to a cave. What they discovered is neighbors and Umbrians farther afield who went out of their way to make their idea come to fruition. The people weren’t curing the sick, but they did help an American’s winery get started.

“In the U.S. you could never do this,” says Thomas, tall, fit, bearded and looking younger than 69 years. “You never could. You have to understand that this zone is unique. There is still deep underneath the Umbrians in this area are still connected deeply with St. Francis and the mentality of St. Francis.

“It’s beautiful. And it’s one of the reasons I like it so much.”

This story began in 1997. Thomas, raised on Chicago’s North Side, had gone to the University of Washington and later to San Francisco at age 25. Working as an artist and part-time at an art gallery, he met Claudia in ‘97 at a museum event. She moved back to Italy and they reconnected in 2000 when the American Academy of Rome brought him over as a visiting artist for three months. They then brought him back a year later.

They eventually moved to her native Marsala, Sicily, where Thomas continued to make and sell art. However, in 2004 he wanted someplace closer to Rome which he loves and has an airport for convenient shipping.

“We took a compass and drew a circle around Rome,” Thomas says. “We just started round the perimeter of Rome and out and out and out until we found something we could afford. We didn’t have much money. We couldn’t find anything and we were getting kind of desperate.”

They arrived in Todi, a charming collection of stone houses, palaces and lightly trodden windy alleys on a hill 35 miles south of Assisi. The locals, unlike Californians, were encouraging them to stay. They found this house.

Then they learned the price.

“We said, ‘Oh, well, there’s no point then. We can’t afford this place,’” Thomas says. “They said, ‘No! Just make the family an offer because you never know.’”

They offered what they could afford — two-thirds less. The owner didn’t laugh. He didn’t explode. He agreed. But then there was the matter of the geometra, the pseudo real estate agent who helped them find the place.

“They get a percentage,” Rizza says. “We were short 500 euros. We said, ‘We’re going to buy but you’re going to have to cut your fee.’ And he did. We had no excuses. He agreed so now we have to BUY THE FUCKING PLACE!”

The home, located at the end of a long dirt road on a hill on Todi’s outskirts, was once a tiny fortress and still sports the three-story stone tower used as a lookout for marauding armies during war-torn Umbria in the 13th century. At the time of purchase it looked as if it hadn’t been refurbished since then, either. What is now the dining room was outside. They lived in the tower and what is now the living room. They slept on the floor the first night. It was February and their lone heat was each others’ bodies. The fireplace was gutted. Thomas tried to make a fire and the whole room filled with smoke.

“It was kind of a hole,” Rizza says.

They returned to Sicily to regroup and came back in the summer. They hooked up a shower in the back and used the sun to heat plastic bags of water. Things were looking up. At least they were clean.

Then the good samaritan Umbrians, all seemingly came from St. Francis’ family tree, offered help. The couple met a “crazy” builder fishing on the neighboring Tiber. Ol’ Italo, “Mr. Italy” as Thomas calls him, rarely wore shoes and walked with a gait of Johnny Depp in “Pirates of the Caribbean.” But he was pretty handy with his hands and offered to fix the entire house to their liking for 10,000 euros. They borrowed the money from Rizza’s brother and Italo moved in.

Italo noticed nearby an old vineyard, a throw-in during the purchase. He asked if he could take the grapes. Sure, they said. Why not? They weren’t going to do anything with them.

What do they know about making wine?

“The next spring I came up to check on things and he was here,” Thomas says. “We agreed to meet, He said, ‘Oh, you’ve got to try the wine!’

“‘What, the wine is ready already?’”

“‘Oh, yeah! It’s much better this way. It’s fresh.’”

“Oh, it was the worst wine I’ve ever tasted,” Thomas tells me. “But I couldn’t tell him this. When I went back home to Sicily, I told Claudia, ‘Jesus, that was the worst wine I’ve ever had. We can make better wine than that.’ So we started making plans.”

Thomas dug into research like he’d soon dig into the soil to plant vines. He connected with friends in the California wine industry for advice. He went to California to take weekend classes.

They returned to Umbria popping their corks about someday popping real corks. Then they ran into the biggest roadblock, bigger than money or weather or vine disease.

Italy’s bureaucratic red tape.

Turns out, landowners own only one meter of land underneath the surface. In Umbria, which has very strict rules for planting grapes, you must buy the rights to plant and then wait for permission before planting vines. For an American, that’s as foreign a concept as the Italian language.

“He was like, ‘This is my land!’” Rizza says. “‘And I do whatever I want to with my land!’

“‘No you can’t.’”

“‘You and your stupid Italian mentality! You’ll never go anywhere!’

“He was planting and I was chasing after him to comply with everything.”

The couple are laughing now. We’re eating ribollita, a hearty farmer’s vegetable stew, and ossobuco, the famed Lombard dish of veal shanks braised with fresh vegetables, white wine and broth. We’re sopping up the sauce with fresh Italian bread and washing it down with their lovely Sangiovese wine on Raphael’s old table.

You couldn’t have a better Italian winter afternoon if Paolo Sorrentino directed it. Suddenly, the red tape and labor and worries seem a lifetime ago.

“You have to go through somersaults,” Rizza says. “We did it the first portion because we planted a half hectare at a time. We decided to put up the money ourselves just so we didn’t have to go through the bureaucracy.”

Expansion and equipment were other matters. They applied for a building permit in 2008 and didn’t receive it until 2015 and they had to rebuild the living room and veranda area. Equipment for making wine? What equipment? Where would they find it? Where would they get the money? Turns out they had a neighbor named Fabrizio who sold farm equipment and was, obviously, another descendant of St. Francis. He had a duster. It cost 1,500. They didn’t have 1,500.

Fabrizio said, “OK, I trust you guys. Don’t you worry. Take the duster. Pay me when you can.”

They later bought a sprayer from him and every month, the couple paid him a little bit, borrowing money from Rizza’s mother, using Thomas’ pension with Rizza selling some ceramics and working at B&B in Magione 40 miles to the north.

In 2007, they were ready to make wine. Again, the neighbors came to help. Three jovial elderly men came by to help collect the grapes. They brought a plastic vat that was bigger than the Fiat Panda it rode upon and dragging a destemmer behind it. All five went to work.

However, it wasn’t really work.

“They’re really old guys,” Thomas says. “They’re between 85 and 90. But they’re spry and smoking cigarettes like fiends. By the end of the night, after doing all this stuff and getting it into the vat, I never had so much fun in my life. I laughed so hard because these guys were great. They loved life.

“That got me hooked.”

Thomas made two barrels of what he thought were two pretty good wines, made with 100 percent Sangiovese grapes. Terramante (www.terramante.com, info@terramante.com), a combination of the Italian words “terra” (land) and “amante” (lover), was born. So were Iubelo and Laudatus, his two wines named with local ties. Iubelo was the name of a poem written by Umbrian friar Jacopone da Todi, who following St. Francis’ lead, gave away all his possessions. He also wrote “Stabat Mater,” which remains one of the great hymns in the Catholic Church. Laudatus, a Sangiovese-Sagrantino blend, comes from a Latin word, laudato, which means “praised” and is all through St. Francis’ religious song, “Canticle of the Sun.”

Cute names, but the true test was taking it to California where his friends would judge.

“They said, ‘This is great wine. You should actually try to sell this stuff,’” Thomas says. “‘You should really think about making wine.’”

His research continued. He looking into the best clones, the best planting materials, the best harvesting strategy. He became a sponge of wine knowledge.

He only had five rows of grapes but little by little the plot grew. He now has five acres and through 12 years of trial and error, has produced a wine that is starting to sell and get recognition. One Belgian passing by loved the wine and bought a couple of cases. What Thomas and Rizza didn’t know was that man’s wine club was voted as the best wine-tasting club in Europe. The club returned and bought 50 cases more.

Then wine writer Jane Hunt, a master sommelier, liked the Iubelo and asked Decanter magazine to consider it for its list of top 100 wines in the world under 50 euros for 2017.

We get in their car and go farther up the hill to their winery. The three-story stone building overlooks the gorgeous green Umbrian valley. The small building, where friars also made wine in Medieval times, holds 14 barrels and two tanks. He takes a plunger and squeezes out enough from a tank to fill half a wine glass. It’s their best vintage yet, he tells me.

It’s cold. It could use some time on a kitchen counter. But it’s fantastic, rich and fruity and clean.

We walk back outside and I look out at the hills beyond. The farmland is partitioned off like a quilt with olive orchards on top, vineyards in the middle and grains and sunflower plantings in the bottom. I made a mental note to return for some fall colors that might make New England look like Cleveland. It’s noon. I hear church bells peal.

Beauty isn’t the only advantage an Italian winery has over California. After all, have you seen Napa County in summer? No, the biggest reason is economics. Thomas and Rizza struggled early but in California owning a winery is something you only see in movies, which is about the only type of people who can afford it.

A winery in Napa or Sonoma is cool. It’s sexy. Yes, it’s expensive but the tax write-offs are great. The California wine scene has gone corporate. You don’t find wineries in former friars quarters.

“What is happening in California, particularly in the Napa Valley, is land values have gone up tremendously,” Thomas says. “In part this is a result of large international investors as well as, in some cases, personalities. Multimillionaires who go in and buy something because it’s always been their dream to have a winery.”

Thomas says an acre of land in California goes for between $250,000-$750,000. For a minimum five acres, that’s more than $1 million. Thus, that section of Bay Area real estate is outrageously expensive. So, frankly, are the wines.

“As a consequence, it’s difficult for a lot of the original family wineries and they’ve been sold,” he says. “That name may still exist on the winery but they’ve been bought by a large corporation or a group of wealthy investors. So if you’ve invested that much money, it’s not possible to get a profit even if you’re selling your wine at $85-$90 a bottle.”

Their California friend in the family wine business recently sold his winery and moved to Umbria and is starting a small winery to make Cabernet and rose’. In Umbria land goes for about $4,000-$5,000 an acre and in Tuscany, except for the over-the-top Bolgheri region, it’s about $30,000.

“If he sells a bottle here for $15-$20 he’ll end up with a larger profit margin.”

Thomas and Rizza don’t have aspirations of getting rich. They hope to break even next year and maybe if they acquire more land some day they’ll make a profit. They should. I was never a huge Sangiovese fan. I’m a Barolo, Piedmont guy. But his Iubelo is the best Sangiovese I’ve ever had. It’s rich with clean acidity and a bushel of red fruit. It’s great with cheeses, pasta or a Florentine steak. I’m taking home a bottle to make my pasta amatriciana even tastier.

“Sangiovese, when you take it into your mouth and it’s the right temperature,” Thomas says, “it has this quality of blood.”

Now that he’s up to his taste buds in Italian grapes, he may become the touchstone for Americans with similar ambitions of starting a winery in Umbria. I ask him what advice he’d give.

“Decide what part of Italy,” he says. “Take some time. Drive around Italy. Make sure this region is what you’re interested in. What does this region have to offer you that fits into what’s important to you. Maybe the Piemonte is more you. Maybe Puglia is for you. Then of course, are you an urban person or are you a rural person? Very basic life decisions like that to begin with.”

Living in Italy I’ve noticed some of the happiest people living here are wine people. I can see why. They’re outside in beautiful country. The weather often reminds them of heaven. They’re making a product that is not only delicious but healthy. They meet interesting like-minded people.

For me, a glass of wine always represents a celebration of a good day’s work even for someone like me who doesn’t work. But here in Umbria, it’s deeper than that. As Rizza quotes St. Francis:

“If you work with your hands you are a worker. If you work with your hands and your head you are an artisan. And if you work with your hands, your head and your heart you are an artist.”

Responded Thomas: “I still think of myself as an artist, even with what I’m doing.“

Salute.

April 14, 2020 @ 10:13 pm

I loved your story. My name is Rhonda Stoklos and I own Rocca Monte in Fallbrook California. I have only 5.2 acres of land and planted all Itlaian varitials. Montepuliciano, Aglianico, Teroldego and Fiano. I too have a dream and am doing this on my own.

I hope to visit when this horrible Virus passes.

Keep up the good work.

Regards,

Rhonda

March 12, 2021 @ 8:19 pm

I have a five-acre Pinot Noir vineyard near the Anderson Valley in Northern California.

Bought 20 acres with almost nothing on it. developed it over a ten-year period with all the money I could make as a chef in Mendocino ( sadly, not very much) built barns Irrigation ponds a House, mostly by myself with the help of more knowledgeable locals. I have since started a very nice northern Italian restaurant with an attached Italian import store. I am 68 so as I contemplate retiring my wife and I have been looking into Italy as a good fit. When I came across an 11acre parcel in Abruzzo with two houses and olive trees at an unbelievably

low price by California standards I’m beginning to visualize 5 acres of Montepulciano. and 3 acres of Pecorino. I loved this Article. it’s like a road map

July 21, 2022 @ 5:27 pm

Joseph – Did you buy the lot in Abruzzo?