Reeling Rio de Janeiro still dancing to a samba beat

RIO DE JANEIRO — I’m jogging along Avenida Vieira Souto which stretches along the sand of Ipanema Beach like a mile-and-a-half-long g-string. Believe me, in Rio de Janeiro, that image is a recurring theme. To my left is some of the purest sand of any beach in the Western Hemisphere, every grain leading to a warm Atlantic Ocean. To my right is the prettiest skyline in Latin America. A series of glittery, high-rise condominium buildings, five-star hotels and high-end cocktail lounges stand watch on the vibrant lifestyle all around me.

Joggers, rollerbladers, cyclists, we’re all pounding the pavement on a well-marked path alongside the busy thoroughfare. Dreadlocked salesmen stand next to handmade jewelry and racks of sarongs, sporting everything from the Brazilian flag to Che Guevara’s bereted head. It’s 8 p.m. in August. It’s winter in Rio and it’s getting dark. Lights of a jagged mountain ahead of me flicker like fireflies as the fading sun disappears behind the majestic mountain, which with its pointy peak and steep incline, if bigger and sporting snow, wouldn’t look out of place in the Alps’ foothills.

Locals tell me not to come to the beach at night. Yet many of those locals seem to be on the beach right now. If thieves ever tried robbing anyone, there’d be so many witnesses there would be a line out the courtroom door. Maybe the thieves would steal the coconut that I’m drinking after my two-kilometer run. In what must be one of the greatest refreshment stands on the planet, the Rio government has kiosks spaced along the jogging path filled with chilled coconuts. If you have a more refreshing taste after a jog than cold coconut water, market it and retire young.

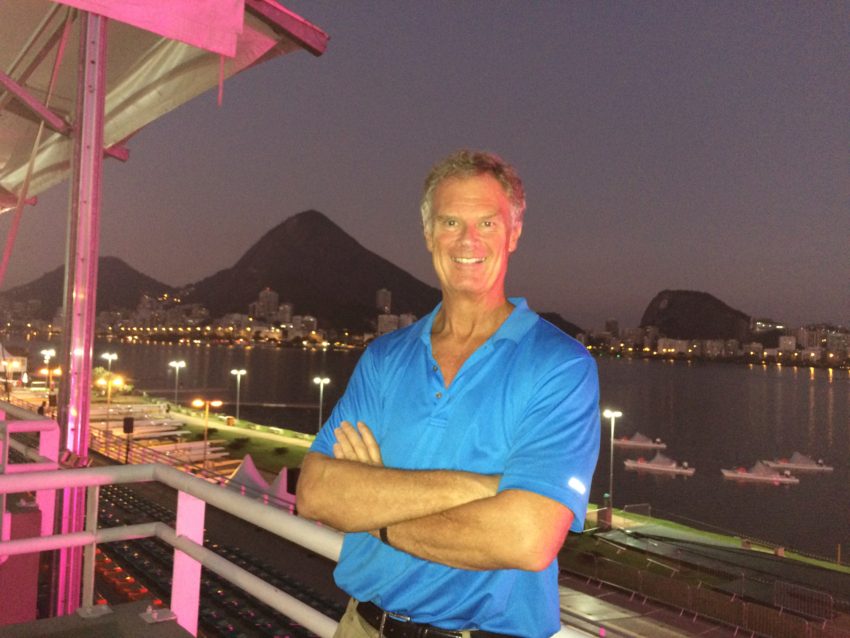

I’m in Rio working for the Olympic News Service at the World Rowing Junior Championships. They’re held on Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas, a huge, beautiful lake just seven blocks north of Ipanema Beach. I covered sports for 39 years all over the world. Nowhere, not the Pyrenees in the Tour de France, Wrigley Field in June or Wimbledon with strawberries and cream in hand, have I covered an event in a more beautiful setting. Surrounding the lake, besides a 4.5-mile-long jogging and bike path, are some of the most exclusive high-rise condominiums in Brazil, priced at $2 million-$3 million ($5,000-a-month rent). Small, pointy mountains that dot Rio’s landscape like sand castles provide an artful backdrop right out of an Oriental tapestry.

I arrive as Rio is bristling from a PR nightmare. An Associated Press report says every body of water in Rio is polluted. Corruption in Brazil’s government has been exposed all the way to president Dilma Rousseff who is clinging to her job. She is the Brazilian Richard Nixon. However, I have news for all the bashers out there.

I love Rio.

I love its pulse. I love its vibrancy. I love its toughness. I love its softness. I love its skyline, its beaches, its weather. I even love its food. This is my third time in Rio and it’s like no other city. Besides having the most beautiful urban beach in the world, Rio de Janeiro seems to be always in rhythm. Music is everywhere. I don’t like music much, yet I can feel the locals, called, not ironically, Cariocas, constantly swaying to a distant beat. Rio is Havana with a democracy. Samba. Bossa Nova. Cariocas seem too mellowed out from constant sun, gentle waves and music to worry about pollution, corruption and crime. Every lyric of “The Girl from Ipanema” still runs through my brain on a 24-hour loop. No song outside The Beach Boys’ in Southern California better represents an area than “The Girl from Ipanema” represents Rio de Janeiro. A beautiful girl in a string bikini walking to the beach without a care in the world. To me, Rio is still that beautiful girl.

Locals tell me life in Rio today is difficult. Middle-class rent is more expensive than in London. Last year’s World Cup didn’t produce the economic windfall everyone hoped. Maybe next summer’s Olympics will make it happen. Nearly all the facilities are finished or on schedule.

But for visitors, Rio is the perfect injection of pure energy. I didn’t have a spot of jet lag after my redeye from Rome landed at 7 a.m. Instead, I checked into my hotel four blocks from Ipanema Beach and three from Copacabana Beach and did what Cariocas do most every morning. I headed for a juice bar.

If this is Brazil’s lone contribution to world cuisine, Brazilians can rest easy. They contributed well. In Rio, they take smoothies to the level of haute cuisine. Go to a juice bar in Rio and you think you’ve walked into an indoor garden. Behind every counter is a mountain of fresh fruit, ranging from pineapples to bananas to papayas to guavas to indigenous fruits I can barely pronounce such as cupuacu (koo-poo-ah-SUE), from the Amazon Jungle; acai (a-SAY), juice made from an Amazonian berry; and acerola (ah-say-ROLL-ah), a real sweet tropical cherry. Pick out the fruits and the clerk cuts them up and puts them in a blender with ice. Soon, wa-la! You have the best smoothie of your life. No smoothie mix in this town.

I walked down Ipanema’s bustling Rua Visconde de Piraja to Polis Sucos, one of Rio’s more popular juice bars. I ordered an acai and acerola juice which came out in a big 12-ounce plastic cup with the thick, reddish-purple fluids slowly slipping over the edges. Cold. Creamy. Sweet. Smooth. Healthy. It tasted like the sweetest purple grape you’ve ever had stuffed into a sweet cherry then liquified with crushed ice. It was absolute heaven. Coupled with a tchai light, a sliced turkey sandwich covered in white cheese and tomato and served on flatbread, I couldn’t have had a better welcome to a city if my room had a throne.

Brazil isn’t known for its food. No one walks around hankering for “jerked meat,” especially not out loud. Rio isn’t known for its restaurants. You don’t go to Rio to eat. But if you know where to go and get the right advice, eating can match drinking as a Rio highlight.

My best friend in Rome, Alessandro Castellani, lived in Rio for four months writing soccer and recommended a rodizio called Carretao. Normally, I treat chain restaurants like chain letters. But also recommending Carretao was a colleague in Rio, Mauricio Savarese, a fine journalist in Sao Paulo who knows soccer, politics and Brazilian food with equal brilliance. A rodizio is a Brazilian all-you-can-eat carnivore fest. Two rules: Don’t eat lunch and don’t bring a woman. They don’t eat enough. They’re a waste of money. Go ahead and bring a vegetarian if you want to watch them get nauseous. We sat down at a huge round table in the Copacabana branch and waiters carried giant skewers covered in sirloin, pork, chicken, ribs, parmesan-covered beef, Brazilian sausage and a few other forgotten meats for which my mind, like my stomach, no longer has room.

A couple nights later, we went to the Academia da Cachaca. On the menu is a dish from northeast Brazil called an escondidinho. Among its ingredients is cassava. Cassava is a starchy root similar to yucca, an aptly named vegetable as that’s exactly what cassava and yucca taste like. Cassava is absolutely indestructible in droughts, floods or locust invasions. Hell, locusts won’t even eat it. Its durability is a reason why it’s huge in the Third World. Estimates indicate that it provides the basic diet for half a billion people. As my University of Oregon professor in Latin American Geography described it, “It’s mushy, it’s fattening and has absolutely no flavor. But it keeps you alive.” I’ve had cassava on trips to the Amazon and in cheap diners around Brazil. It tastes like mushy lard.

I wanted nothing to do with a deep-bowl dish that included cassava. However, Mauricio insisted I at least try a bite. It didn’t look bad. With carne seca (the aformentioned “jerky beef”), onions, cream cheese and pecorino cheese, it looked like like a beef souffle. The one bite was a terrific mix of lumpy, salty beef and onion with the cassava providing a rich, creamy texture and the pecorino a crusty, cheesy topping. I immediately ordered my own bowl and, of course, a caipirinha.

The caipirinha is Brazil’s national drink. It’s as simple as a hammer and just as deadly. It’s made from cachaca (Kah-CHAW-saw), a distilled liquor made from sugar cane juice that’s not nearly as sweet as you might think. But two ounces of it with a teaspoon of sugar in a tumbler or a tall glass filled with crushed limes and ice cubes, and you have the best drink with which to watch a sunset. It is also not bad with which, in Rio, to watch a sunrise.

I saw no sunrises on this Rio trip but I did sample Rio’s famed nightlife after my last day of work. Rio’s club scene is like a long, pulsating snake. It wraps around the city with beats in every corner. On my first trip in 1998, I went to a samba club in a bad part of town and wound up knocking over a table full of drinks that weren’t mine. Dancing Brazilian was not on my Rio to-do list. But there I was in Londra, a club in the high-end Hotel Fasano, an Italian-themed hotel (thus, the name “Londra,” the Italian spelling of London) across the street from Ipanema Beach. In Londra, you go from Italy to Great Britain in Brazil. You leave a lobby of overstuffed white couches and brilliant white lighting to a room with British rock albums and photos of British rock stars lining the walls. On the back wall hung a giant Union Jack.

The music, of course, was dreadful. The problem with nightclubs is the music is the same from Barstow to Bangkok. It’s BOOM! BOOM! BOOM! BOOM! With the occasional BOOMBOOM! thrown in. Yet Brazilians have so much rhythm, so much freedom of expression, they make it work. I saw one long-haired blond man in his 30s with an untucked white dress shirt dipping and swaying and grooving to every single stilted beat. It was like he choreographed his dance to the music that afternoon. His dancing was so lithe and happy, a pretty young, curly-haired brunette ran up and joined him dancing right in front of the bright, back-lit bar. Her intentions, with her wide smile and wilder hands and eyes, would only be misconstrued by a Tibetan monk. Yet the man smiled, held her face softly and was a perfect gentleman. He finally broke away for some more moves. Apparently, he was more interested in dancing than sex.

I returned to the hotel at the reasonable time of 4 a.m. In Rio, if you’re not out until at least 9 a.m., you’re not trying. However, dropping my head to my pillow, just before going to sleep, I realized I made a mistake. I left my credit card at the club. It was five blocks away. I then went back to the first warning I heard: Don’t walk on the beach at night. I was not walking on the beach at night. I was walking on it at 4 in the morning. Still, I saw people walking along Vieira Souto. None looked capable of helping top Rio’s 2014 number of 1,207 homicides.

In another two hours the sun would come up. In Rio, the sun has been setting for a long time. But this is one city that is always very hot.