Rome’s birthday brings back fond — and not so fond — memories of my days in gladiator school

(Editor’s note: This is the lead chapter from my 2006 book, “An American Gladiator in Rome: Finding the Eternal Truth in the Infernal City.” Reprinting the chapter is in honor of Rome’s 2,770th birthday Friday. The school still exists today. Cheap plug: If you like the chapter, the book is available on Amazon.com. Just hit this link.)

LIFE AS SPARTACUS: INSIDE ROME’S GLADIATOR SCHOOL

I stand in a sandy pit surrounded by torches in front of three dozen tourists hoping a stiff breeze doesn’t fly under my tunic. It’s way too short, and I weigh the embarrassment of revealing my brand of underwear to strangers against taking a Latin oath from a chunky tie salesman wearing animal skins.

It’s graduation day at Rome’s La Scuola dei Gladiatori (The Gladiator School), and I have just demonstrated how to take a sword and skewer, fillet and behead an opponent in six simple strokes. Two months of training had culminated in this ritual, surfacing in Rome after a 2,000-year absence. Somehow I don’t think when Spartacus took this oath, he was worried about bending over.

“Paratus es virga caederi, flamma consumi, et ferrum recipere (Are you ready to strike with the rod, to be burned by the fire and die by the iron?),” Tiger Skin asks solemnly.

“Ita (Yes),’’ I reply.

“Possit ignis suam vim donare, posit tus deorum fidem donare! (May the fire give you the strength and incentive for loyalty to the gods!)’’ he says.

“Nunc Caratacus, gladiator sum! (I am Caratacus, the gladiator!)” I say. I walk up to a stage filled with Roman soldiers and vestal virgins and received a diploma from a middle-aged printer who’s a dead ringer for Emperor Nero, except for the cell phone. I walk away to polite applause and wonder what one does with gladiator skills in the 21st century except maybe visit former bosses. I know one thing. After two months inside the Gruppo Storico Romano (Roman Historical Society), which runs the school, I know gladiators have not just returned to Hollywood. They’ve returned to Rome.

This group is made up of every walk of Roman society from cooks to flight attendants and is into this up to their breastplates. They have an entire armory of authentic weapons and armor. They refer to each other by their gladiator names. They hold gladiator battles, complete with weapons and, yes, animal skins, all over Italy. They have read Cicero’s ancient accounts of gladiators – in Latin. This whole love affair with Rome’s bloody past began four years ago. Sergei Iacomoni, a grizzled, rugged 49-year-old printer for the Bank of Italy and sometimes Nero, had seen the movie “Gladiator” five times. Already a wild fanatic about Roman history, he researched everything he could find on weaponry, fighting techniques and lifestyles of the ancient gladiators. He approached the Roman Historical Society about starting a school and today students take twice-weekly two-hour courses for two months and learn how to fight like men who inspired a nation, historians and movie studios everywhere.

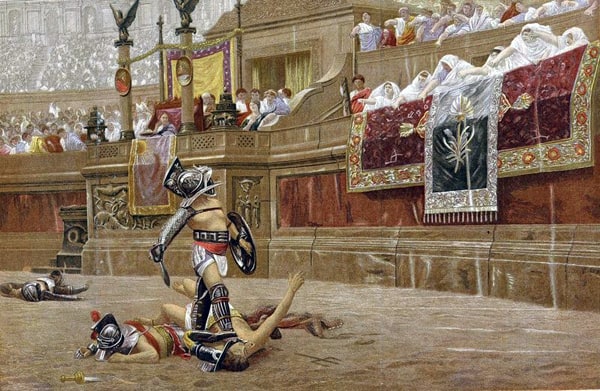

Gladiators were the main event in an era when hundreds of thousands of men were slaughtered in the name of entertainment, when the Colosseum flowed with blood from gory killings by man and wild beast alike. Hollywood wouldn’t dare touch the true accuracy of what I learned really happened.

“I am Roman,” Iacomoni says. “This is my history.”

More than 70 students had lied about being ready to die by the iron. I am one of them.

***

My first exposure to gladiator school came like the many who watched me butcher Latin that day. I went to the historical society’s headquarters and watched a performance. I had read brief European dispatches about the school and pitched a story about joining the school for Smoke magazine. They bit as did about a half dozen newspaper travel editors. I made a couple phone calls and a man who gave his name as Morpheus invited me to the headquarters on a sunny March afternoon. I nearly fell off the bus when it dropped me off. The headquarters is on Appian Way. That’s the same road where, in the year 73 B.C., 6,000 gladiators were crucified after the Roman legions put down a near successful revolt (see “Spartacus, first failed union leader”). Down an adjacent gravel road is an abandoned bus garage where the Roman Historical Society has built a miniature Roman village. A small fire burns on a white Roman stand as I pass a tiny wooden cashier booth. A giant iron gong hangs with a wooden mallet. A life-size catapult rests on the other side of the sandy pit. Inside a tiny archway with the word “Taverna” is a table complete with ancient table settings and plastic food. I keep waiting for the sound track from “Gladiator.”

Morpheus hears my voice and steps outside to see me gazing at pictures of modern gladiators fighting in various Italian villages.

“We put a weapon in a person’s hand and they say, ‘What do I do?’ ” Morpheus says. “ ‘How do I kill someone?’ ”

Morpheus is really Guido Pecorelli, a short, wiry, 25-year-old student with short-cropped hair, Fu Manchu and dark, piercing eyes. Morpheus is his gladiator name, a name he took from the Greek god of dreams. I didn’t ask why. I was just told not to call him Guido. Ever. He takes me inside the gladiator armory. Along one wall are long spears lined up like giant toothpicks. On another row are helmets of various shapes and functions. Some have full faceguards. Others have large bulky points on the top. A few have armor stretching all the way down the back. Also along the wall is every blade man has ever known: axes, machetes, sabers, daggers, tridents the size of sculling oars. Full body armor, from leg guards to arm shields to chest plates, are scattered around like throw rugs. The place looks like a training camp for vandals. You could outfit three government coups from this room. I thought it was a nice touch that they added brooms, authentic replicas used in the Colosseum to sweep away blood and detached limbs.

I pick up one of the machetes. It was heavy, real heavy. The average machete weighs about seven pounds, the same as in Ancient Rome. All the weaponry and armor are hand made, and the ironworker soldered over the points and edges of the blades to make them less sharp. You probably couldn’t cut off a man’s arm, but you certainly could break it. Then again, I can’t imagine these guys passing themselves off as cold-blooded killers. The school’s graduates are normal overweight, middle-aged Romans who would look more fitting in a café watching a soccer game. The gladiator image loses some glitter when you see a guy in a tunic and full body armor with an ax in one hand and a cigarette in the other.

One guy is the spitting image of Joaquin Phoenix, the villain in “Gladiator.” Morpheus’ father, Giuseppe Pecorelli, oops, I mean Pertinax, stands about 5-foot-3 but screams real loud. He says he wanted “to get in touch with my warrior past.” These guys are serious.

“The Roman Empire was all over Europe,” Iacomoni says. “Everyone has something Roman in their history. I wanted to do something to give new life to what was beautiful and important. It is something from your history. Try to discover again your roots.”

I meet Giorgio Franchetti, known as Ferox, a 32-year-old flight attendant for Alitalia wearing full leg armor, armored shoulder pads, a leather belt with iron rings and a long gray cape. He’s carrying a machete.

“I left my house like this,” he says straight faced. “After a long period of fighting like a gladiator, you feel like a gladiator. At night here, when you don’t see modern Rome, with this magic and it’s dark, you can think back to that age. You feel the spirit. You feel a shiver.”

Then the demonstration begins and out steps a massive hunk of humanity named Aureus, “The Golden One.” Leonardo Lorenzini stands 6-foot-2 and weighs 280 pounds, about the size of three average-sized Romans. He has a roll of fat but his shoulders and chest are massive. He wears nothing but a bearskin rug across his chest. Ever see those anthropological charts showing the evolution of man? This guy is the third one from the left.

After a parade of gladiators carrying an arsenal of weapons, Aureus walks into the pit in front of about 60 high school boys visiting from Northern Italy. Up against him is this young kid, a muscular, good-looking Roman carrying a shield and a machete. Aureus smashes his ax against the shield and it reverberates like a gong. It’s the first audible “ooh’’ I hear from the crowd who keep yelling “Grande!” whenever Aureus comes by. The young kid takes a vertical swipe and Aureus catches it with his ax. Aureus follows with a backhand to the kid’s shield, knocking him into a backward somersault. The kid comes up charging full speed and Aureus, showing the agility of an NFL linebacker, steps away and uses his sword to deftly flick away the kid’s machete.

Seeing his opponent defenseless, Aureus drops his weapon and puts him in a bear hug. You can almost hear the bones crunch in Milan. He throws the kid on the ground and grabs his sword. Then, putting his foot on his chest, Aureus yells something unintelligible in Italian. The high school boys gleefully put their thumbs down, and he shoves his sword inches from the kid’s neck. That’s how the gladiators did it – except they didn’t miss the neck. In the background, on a small loudspeaker, I can hear the soundtrack of “Gladiator.”

Morpheus sees me as I’m about to leave.

“See you at practice Wednesday night,” he says with a demonic grin.

***

Morpheus and Pertinax pick me up in their silver Renault near the Vatican. We drive west out of the city past drab 1960s and ‘70s apartment houses to a square white building that looks like a DMV sub center. It’s one of the many simple, municipal gymnasiums the city built in the ‘90s. It’s about three-quarters the size of a high school gym covered with tumbling mats. One mat hangs from the ceiling to serve as a wall, separating us from a girls gymnastics class. Our section of the gym is lined with mirrors.

We are a long way from the Colosseum.

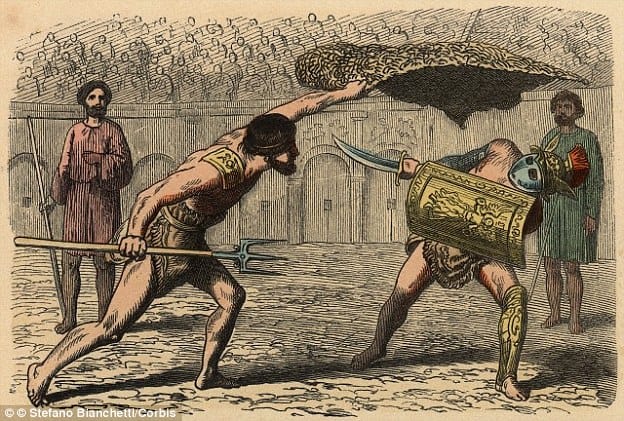

After a brief warm-up, Morpheus puts me under his wing. He gives me a crude, wooden practice sword wrapped in duct tape and shows me the crucial six-step program, or six ways to turn your opponent into second base. We stand in front of the mirror and get in the ready, or guardia, position: one foot slightly ahead with a bend of my knees and my hands up, one holding a wooden sword and the other an imaginary shield. It’s very similar to boxing except my weapon can’t hurt a hamster.

“Your right arm is your friend,” Morpheus says.

The six blows are really quite simple. For example, fendente is the playful act of smashing a sword onto the top of a man’s skull, splitting it in two. I guessed I wouldn’t be learning that word in Italian class. The others are more direct: alto dritto, a parallel swing to the neck, similar to hitting a high fastball in the way you get your arms extended; basso revescio, bending down and cutting below the knees, very effective for limiting your opponent to crawling if you have a tee time to catch; and affondo is a straight thrust to the stomach, the best way to kill a man if you want to see them squirm and bleed for a while. Alto revescio is a backhand alto dritto, and one blow is repeated each sequence.

Despite how simple they sound, they’re quite awkward. On the basso revescio I find myself leaning over on my follow through. I look like I’m watering a small plant. “You’re leaving yourself too open,’’ said Guido as he takes his sword and pretends to cut out my lower intestine. “Keep running through.’’ To help my form, we stand in front of the mirror and he tells me to look at my reflection as the opponent.

“Now pretend to cut off your head,’’ he says.

I fulfill a dozen copy editors’ fantasies by making a perfect parallel slash right below my chin. I look like an outtake from “The Omen.’’ We spend the next 90 minutes going through the same six strokes over and over again. Morpheus then shows me the defensive moves. He goes for the top of my skull and I hold up my sword just above my forehead parallel to the ground. It catches his sword in a perpendicular clash. He goes for my neck and I hold up my sword like Hano Sono’s laser in “Star Wars.’’ I twist my body to the left and catch his sword; I twist it to the right and catch it again. I go low and bend down and strike my sword toward the ground like it’s a putter and I just missed one from 2 feet.

“Perfetto! Perfetto!” he says. Suddenly, I want to put on a tunic and invade Greece. We go back and forth for 15 minutes. When it’s all choreographed and done properly, you never touch a hair. You also feel like you are partners in some weird ritual. “This is like dance steps,’’ I say innocently.

Guido stops. He looks as if he was about to take off the duct tape.

“This is not a dance,” he says, indignant. “This is a fight.’’

However, I can see where it would be a good workout. Before each practice, we do a half hour of calisthenics ranging from sprints to extended push-ups to hundreds of stomach crunches. Guido is real wiry. He’s short and taut. He said he lost more than 30 pounds in his one year of gladiator school. However, he was also young. I would be 46 in 15 days. I tell him I might be too old for this.

“You’re not too old,’’ he insists. “When you stop playing, that’s when you become too old.’’

During my first two weeks, I felt 66. I’d spend 90 minutes a night shuffling up and down mats, tapping my sword against my partner’s. It took me half a second to tell my basso from my alto. It had all the ferocity of two really ugly people doing the tango. In the Colosseum, I would’ve been American shish kabob by the time I reached someone’s reveschio. Pertinax would yell “ALTO DRITTO!” and I’d go through my mental flash cards before delivering a nice, soft even slice toward the neck like a Pete Sampras drop shot. At one point, Morpheus took my wimpy little fendente and told me to pretend I’m hitting an overhead smash and not patting a dog on the head.

“This is supposed to be a fight,” he says. “It looks better. It isn’t ‘tap, tap, tap, tap.’ ”

They once put me in the middle of the mat between Morpheus, Pertinax and another student, a portly, scruffy soldier in the Italian army who looks like Friar Tuck. Each guy went at me with a different blow, I’d have to defend, turn to the next guy and defend his blow, all in the same sequence. When done at full speed with full force, you look like one of the Four Musketeers defending a French castle. I couldn’t defend a cappuccino machine. I got my pivot foot confused and staggered around, nearly falling on various forms of wooden cutlery. I only got really frustrated once, but I calmed down. This isn’t golf. In gladiator school, it’s bad form, not to mention bad luck, to throw a machete.

“Tempo. Tempo. Tempo. (Time. Time. Time.)’’ Morpheus tells me.

So I take time. Over the next month, my six blows become my daily routine, my six commands my mantra. I’d come home from Italian class and practice my blows with a cheese knife. I’d shuffle up and down my marble floor, giving a fendente to a lamp, an alto dritto to my laptop, a basso revescio to a wastebasket. I’d walk up the stairs of my apartment building and give a Latin “Hail, Caesar” salute to perplexed resident cats. I’d stand before a mirror wearing a towel, imagining what I’d look like in a tunic. I stopped just short of calling my girlfriend “wench” or refusing silverware when I ate. By the fourth week, I about nailed it. I was swinging my little wooden sword in long, glorious death slices, ignoring Pertinax’s instruction of “Piano! Piano!” (Slowly! Slowly!). I shouted out “FENDENTE! ALTO ROVESCIO!’’ as I wheeled around the mat defending three men at once while delivering blows just as fast. It was starting to get fun. It was also starting to get scary. I fight off the urge to ask Pertinax to replace the wooden sword with the 15-pound ax. I want to draw blood even if it was my own.

I slowly become accepted. They even give me my gladiator name – two, in fact. The first was Flavus, Latin for “blonde one.” Flavus? It sounded like a disease. Then I off-handedly tell Morpheus I come from Scottish descent, and he races out to the car. He brings back a list of Scottish names. “You are now Caratacus.” Who? He tells me Caratacus was a Scottish warrior whose battles against invading Roman armies were so legendary he lived forever in Roman lore. I think it’s a real hip name until I mistakenly learn Caratacus was later beheaded in battle. I wonder how far these guys took this gladiator stuff.

Once I got to know them, the gladiators seem normal. Morpheus started in judo where his father’s a black belt, moved on to archery then to the medieval games held in various Rome parks on Sundays. His father learned about the gladiator school at a Rome book fair.

“Judo is a different kind of culture,” Morpheus says. “That’s the Orient. I’m Roman. Roman culture is 2,000 years old. I can do something that is mine.”

There have been three women come through the school, and none has stuck around as long as Barbara Milioni. Known as Nemesis, the 24-year-old entertainer was a black belt in judo at 16 and also a medieval war games refugee.

“I always liked men things,” she says. “I never played with a Barbie. I was playing with a car or a pistol.”

When friends grew out of the medieval games, a friend told her about the gladiator school that received very little notoriety in Rome. She had found her niche. She’s short but powerfully built with big shoulders and muscular thighs. She also looks typically Roman with the dark, beautiful face of a runway model. She’s a huge hit.

“For me, the comment you hear everywhere is ‘Xena,’ ” she says. “That’s my nightmare. Always. Always. But I hear also, ‘Hey, the girl is a good fighter.’ When they look at a girl, especially in something like this, I hear, ‘Oh, God, it’s a girl with all the men.’ But when they see me fight, they go, ‘Oh, she’s not bad.’ ”

The unofficial star of the show is Aureus. A 26-year-old cook at an elementary school, Aureus got tossed out of kickboxing for hitting opponents too hard. He often warms up for gladiator practice by high-kicking a heavy 6-foot stationary dummy clear into the gymnastics class. He saw a gladiator demonstration outside Castel Sant’Angelo, a 1st century castle near the Vatican, and said he’d do anything to join.

“I love a show,” he said one night after practice while blow-drying his back. “I love Gruppo Storico. I love fighting, but this is more. This is like warriors. If I was in a battle, I’d want another battle.’’

His dark, curly hair and blonde streaks make him look like a surfer on steroids. But there is nothing laid back about him. Some gladiators refuse to spar with him because they still value their lives.

“In his mind, he lives in the gladiator age,” Ferox says. “It’s true. He trains to fight all the time. He’s always trying to get stronger, harder. He makes the heaviest hits. He’s so serious. He smashed right through my shield and nearly broke my hand. If you met him 2,000 years ago in the Colosseum, you cross yourself because you’re going to die.”

In one of my most ill-advised bouts of over-confidence, I ask Pertinax if I can fight Aureus. During the second month, we often had free fights. There were no sequences. No planned attacks. We used foam rubber swords. Using real weapons for free fights is way too dangerous, they say. Still, I want a shot at the star, the king gladiator, the man thousands of ancient Romans would have paid good money to see. I want to throw away the wimpy foam rubber and use forged iron. Pertinax says no. Aureus say yes. After much pleading, Pertinax reluctantly agrees only if we did it in planned sequence – slooooowly.

Pertinax slips my forearm through the two leather holders behind his iron shield. It’s like carrying a door of a bank vault. While going through the sequence, Aureus gives me a basso rovescio to my lower leg and I try slamming his ax with my 7-pound sword. I miss. The sword hits the top of his finger and produces a half-inch gash.

“NO BUONO! (NO GOOD!),’’ Pertinax says and takes my shield.

“NO PROBLEMA! NO PROBLEMA! (NO PROBLEM!),” Aureus reassures.

Uh-oh. Now I’ve made him mad. His eyes bore in on me like I’m a slice of Tiramisu. After a couple more blows, I miss a block on another basso rovescio and suddenly, heading right toward my frontal lobe, is a 15-pound iron ax. Aureus stops it one inch from my nose. My heart drops into my jockstrap, and I suddenly visualize what the last thing gladiators saw 2,000 years ago before getting their heads axed open like a cantaloupe.

A man like Aureus smiling over his blade.

***

Four things “Gladiator” didn’t tell you about gladiators:

* The warm blood of a fallen gladiator was believed to cure epilepsy. The Ancient Romans worshipped courage, and few in Rome were as revered as successful gladiators. Russell Crowe’s character showed how a gladiator could win freedom in the arena but if the movie was accurate, Crowe would have survived and built a villa on Palantine Hill with a bevy of young maidens. Then he’d go back to the arena every Sunday.

That’s because many gladiators liked it.

While they all began as slaves, the successful ones started earning high wages from agents and emperors whose longevity in office often depended on their ability to placate a bloodthirsty populace. Nero gave the gladiator Spiculus a palace. The son of Veianius, another famous gladiator, was made a knight. Ancient scratching on the walls in Pompeii called Celadus, “suspirium et decus puellarum” (the girls’ hero and heartthrob).’’ Possibly the most famous gladiator, Flamma, had his face appear on Roman coins as Mars, the god of war. Sculptors made statues of him. A female admirer gave him an estate. Street walls were inscribed, “Flamma is a girl’s sigh and prayer.” No wonder this guy refused the wooden sword, the symbol of a gladiator’s freedom, four times. Considering the tunics these guys had to wear, these are real rags-to-riches stories.

They also received a few breaks in the arena. Highly successful gladiators were rare and killing one didn’t help future attendance much. When two faced each other, it wasn’t always to the death. It was often to first blood. If a gladiator fell, the victor raised his sword to the crowd with his foot on the man’s chest and his sword over his head. The emperor waited for a crowd’s verdict and would often give mercy. But pity the poor fallen gladiator who was favored and cost the crowd money.

Gambling ran as rampant as the blood.

* Gladiators were often Romans. They were traitors. Anyone escaping the tough regiment of the Roman legions was turned into a slave. No wonder they had the biggest army until World War II. They also turned POWs into gladiators, one reason why you saw so many gladiators with different skin color. Since the Roman Empire stretched from Great Britain to Central Asia, the gladiator pens looked like a UN Executive Board meeting in tunics.

* Gladiator games began to honor the dead. According to Daniel Mannix’s excellent 1958 tome, “The Way of the Gladiator,” the first reports of gladiators come from 264 B.C. The brothers Marcus and Decimus Brutus, members of the Roman aristocracy and obviously bored, wished to honor their dead father by more than just the usual animal sacrifice. The brothers had heard that in prehistoric times, slaves fought over the grave of a popular leader. Why not bring back that ancient custom? Thus, more than 600 years of blood sport began.

It became huge. Three pairs of gladiators started it. By 145 B.C., 90 pairs fought over three days. It became a necessity for anyone running for office to put on gladiator games, and each emperor tried outdoing his predecessor. Marcus Aurelius held 230 one year. It was a difficult time in Rome. Warfare and violence were constant. After wars, emperors would stage gladiator battles to show how they killed the enemy. They tried new weapons in the arena for future use in the battlefield. The populace worked inhuman hours trying to keep the war machine grinding. Much as the National Football League does for American society, gladiator games became the diversion for the Roman society. Romans flooded into the makeshift arena in the Forum. The emperors Vespasian and Titus scored big points in the ballots in 80 A.D. by building the Flavian Ampitheater, later known as the Roman Colosseum. It seated 50,000 and admission was free. Theaters emptied in the middle of plays when word of gladiator games surfaced. Women were known to orgasm in the arena. Prostitutes lurked under the archways of the Colosseum to service men turned on by the bloodshed.

It eventually ended around 400 A.D. when the falling Roman Empire gave way to the rise of Christianity. The extreme measures the church took to counteract the bloodshed are one reason many historians believe Rome is the center of Christendom today.

And speaking of Christians …

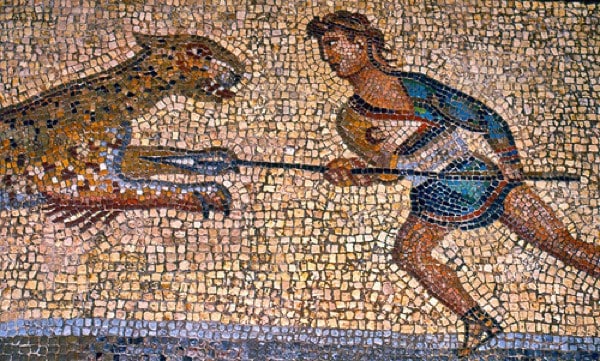

* The gladiator games were far bloodier than ever depicted on the big screen. The gladiator battles were headliners of games also used to execute Christians, deemed heretics and terrorists by the Roman Empire. Christians viewed Rome – not entirely inaccurately – as the second Sodom. Then again, since at the time Christianity was just slightly older than your basic bar of Ivory soap, the Christians were considered heretics and suffered wholesale slaughter in the most inhumane manners possible. They were thrown in defenseless against wild tigers starved for a week. According to Cicero, it took about 30 seconds to corner and kill the poor, sniveling Christian and another half hour to eat the sinew, flesh and bones. (That’s one way to shut up sidewalk evangelists.) They were hooded and given sticks and torn apart by wild dogs. Apparently, the screams could be heard clear across Rome. They were covered in pitch and set afire to provide light, apparently marking the first night games in sports history.

For a few laughs, they would put a Christian in with two wild bears and given nothing but a musical instrument. They were told to imitate Morpheus (no relation to said gladiator), a Greek with music reputedly so sweet he could put to sleep wild animals. That wasn’t easy with two bears eyeing your head like a fudgesicle. Of course, his futile attempts and subsequent mauling were of great amusement to the Romans who hated Greeks and Christians.

The death tolls were astonishing. Augustus killed 10,000 Christians over eight shows. Emperor Trajan had 11,000 people killed over 122 days. Diocletian killed 17,000 in a month. They burned incense to help erase the stench.

Nietzsche philosophized that the Romans found no more worlds left to conquer, leaving them with only these sorry exhibitions. The more I learned about my adopted Roman past, the more I questioned what I was doing with a sword in my hand. I asked Iacomoni if he was glorifying one of the most gruesome, embarrassing periods in man’s history.

“Obviously, these are completely different times,’’ he says. “But I respect one thing about the Roman times. In war, when you had to fight someone, you had to be in front and see his eyes. Today, you may kill someone without seeing them.’’

Unsatisfied, I turned to Morpheus whose vision had been a guiding light through these entire two months.

“We’re not glorifying the killing of that time,’’ he says. “We glorify the people. We glorify the genius of the people at that time to build something enormous. The Colosseum was something enormous at that time. You have to be a genius, very powerful, very rich, but also very rich in culture. You must have a government with an open mind to know all the good things of other cultures and taking them for your culture.”

Which is why I’m standing in sand telling 30 tourists I am willing to die by the iron.

***

The closest a woman comes to orgasm when seeing me in full battle gear is a wink from a woman about my mom’s age. It’s the morning of graduation day, and it coincides with the 2,755th birthday of Rome. Every year on April 21, the entire Roman Historical Society dresses in full battle regalia of the gladiators and Roman Legionnaires, the Roman army, and marches from the Appian Way to the Colosseum. My girlfriend, Nancy, recruited (kicking and screaming) as a vestal virgin, and I are late. Way late. The police had informed the group that a road race that morning cancelled our parade. Nancy and I are not informed of this until we were walk up the gravel path and saw heavily armed men in tunics piling into Volvos and Lancias.

Morpheus tells me from the window of a passing car to get dressed and meet them at the Colosseum. As any rational gladiator would do, I become furious. I had no desire to get left behind and walk to the Colosseum dressed like an extra from “Saturday Night Live.” I race into the armory and another straggling gladiator helps me with a Legionnaire’s outfit: a short, very short, maroon tunic; a leather chest protector; a pointy iron helmet and a long wooden stick with a point on the end. I run out to see Nancy desperately trying to keep attached the side of her dress, a long white gown with a slit that violates a half dozen of Rome’s public decency laws. It reveals a lot of leg. A matronly aide at the headquarters hides her eyes as Nancy stagger steps back toward the gravel road. I make a mistake and tell her to hurry.

“SHUT UP, John!” she yells. “I’m wearing a bed sheet for you!”

I shut up.

We turn the corner onto Appian Way and I suddenly feel as if I’m falling into a bottomless cobblestone abyss. Everywhere I look are people. Staring. I may as well have be naked. Considering what I have on, I almost am. From the first car I see, the driver sticks his finger at me – his index, fortunately – and laughs. The next one honks his horn. Others smile and shake their heads. This is THE worst Halloween party I’ve ever not been invited to. I think about covering Morpheus in pitch. Suddenly, a late-model car screeches to a halt and a couple from a wedding get out and take their pictures with us. After that, I throw myself into the role. When people honk, I give the Hail Caesar salute. People give me the thumbs up sign, and I give them a raised fist. Russell Crowe wasn’t this campy.

When we reach the Colosseum, the parade is already in motion through a phalanx of tourists. Nancy falls in line between two tiny identical twins wearing smaller bed sheets, and I jump in with Legionnaires right out of 150 B.C. Tattoos, bent noses, scruffy beards. One guy next to me has a forehead the size of the left-field fence in Fenway Park. He has a huge back and bushy eyebrows. He looks at me as if I paid my way into a fantasy camp, which I had.

I fall into a steady march around the Colosseum to the slow, ominous beating of drums. Tourists surround me. Suddenly, it makes sense. I look through the Colosseum’s sun-drenched porticoes and imagine fighting for my life and honor as my gladiatorial predecessors did 2,000 years ago.

Then Nero buries me.

During a break, Iacomoni walks by and looks me over. He shakes his head. It isn’t good when Nero shakes his head. He looks at my stick and I notice I am the only one without an iron sword on the end. My stick is so much shorter than everyone else’s. I feel impotent. Then he looks at my tunic. He informs me that no Legionnaire in the history of Rome wore under his tunic a pair of gray University of Washington gym shorts. He tells me to take them off. Rome gets nearly 6 million tourists a year. I firmly believe all 6 million were at the Colosseum at that moment. I slip down my shorts to hoots and hollers that would embarrass a stripper. I shove my shorts down my chest protector and continue, slowly — and very humbly — to the statue of Julius Caesar and through the Forum. Tourists give us applause. A Japanese couple pose with me for pictures. One of the city’s phony Legionnaires who pose for tourists year round give us a Hail Caesar salute as we pass. He thinks we are real!

When we finally finish and pile into cars, Morpheus comes up to me in near tears.

“This is the first time in 2,000 years someone with gladiator dress is in the Forum!” he says, panting. “Two thousand years! We passed by the arch and my heart started to beat. I got so emotional.”

When I finally see my reflection in a window, I also feel like weeping. I look like a cross between a deranged stork and a sexual deviant. My legs are too skinny. My neck is so long my helmet makes me look like a real tall lamp. The bill of my helmet hangs over my eyes as if I’m wearing a dinner plate. Surrounding me are all these stocky, grizzled men – real Romans – whom I could see skewering 30 Christians before noon and then for lunch eating live cattle. And I don’t even have a point.

We return to Appian Way and my time in the Roman sun is about over. I give my oath, but want to answer in a much different way.

Magister: “Why are you in this arena?”

Answer: “I want to be a gladiator.” (I want to make an ass out of myself.)

Magister: “You must renounce your name. What is your new name?”

Answer: “Caractacus.” (My idol.)

Magister: “Are you ready to strike with the rod, to be burned by the fire and die by the iron?”

Answer: “Yes.” (No. I’m ready to strike out with female tourists, to be burned by this assignment and to die by embarrassment.)

Magister: “I give you the fire for the strength and loyalty of the gods!

But I play the game and scream Latin commands as I knife the air with my little wooden sword in a group demonstration. I want to join the veterans, all dressed in armor and animal skins as they try to behead each other. Instead, I stand on the sidelines and look down at the oracle proclaiming my culmination of two months work. I notice it was written out to “John Anderson.” They misspelled my name. No matter. It’s no longer my name.

“I am Caratacus,” I said, “the gladiator.”