Traveling to Bratislava: Getting in touch with my inner Marxist

AUG. 22 — BRATISLAVA, Slovakia

Everywhere I went in Slovakia and told Slovaks I was going to Bratislava, I always got the same response.

“Why?”

Bratislava is a capital of a country that prides itself on its rural reputation. Slovaks don’t want to be called country bumpkins, but they don’t want to be called city people, either. It’s like they identify more with a backpack than a briefcase.

“There’s a rivalry between Bratislava and the rest of the country. They see Bratislava as a big city which is quite funny since it is quite small.”

Those words came from a real bright 24-year-old Bratislava native who’s sharing my train compartment to Prague with me. He’s dressed all in black, from his black-rimmed glasses to his monk-like haircut to his black beard. His button-down short-sleeve black shirt makes him look like a priest in training. But he’s totally astute about life in post-communist Bratislava.

“I love Bratislava,” he said. “It’s not as big as Budapest or Prague but if you find the right people it is a wonderful place to live.”

After four days in the Tatras, Bartislava seemed like Manhattan. I was met at the gray, communist-era train station by Gabika, the cleaning lady for my AirBnB. In her 20s, Gabika is cute in a sexy librarian sort of way with black curly hair held up by berets and horned-rimmed glasses. She spoke good English but said little as we waited for the tram.

I knew I was back in a big city when a bearded immigrant, maybe Middle Eastern, wearing a long-sleeved shirt with one sleeve cut off, stumbled around the platform muttering to himself. He had an imaginary conversation, apparently with some rube, as he kept pantomiming a mysterious explanation with wide eyes and a condescending smile.

I kept thinking, If I keep traveling by myself, I’ll end up next to this guy, babbling around the evils of capitalism on a tram platform.

The apartment confirmed my dedication to AirBnBs. It was another wonderful surprise on the road, like getting picked up hitchhiking and getting treated to a home-cooked meal from whatever country you’re traveling through. It had a fully stocked refrigerator, complete with milk, a basket of snacks and a cupboard full of cereal.

As soon as Gabika left, I gobbled down a chocolate sugar cookie, a “typical Slovak biscuit,” the renter’s manual said, and inhaled my first milk in nearly two weeks. A king-sized bed dominates the living room and a pre-World War I radio sits on the writing table, making my 24-hour home look as much antique store as apartment.

The highlight was it’s only a 20-minute walk to Old Town, the anchor for Bratislava’s tourist trade. I had one day to see Bratislava and felt as if I couldn’t last one hour.

My previous night in Poprad went from a quiet evening of rest to a violent, drunken sprawl. I was blogging on this AlphaSmart word processor, which has turned into quite a conversation piece in Eastern Europe. A couple at the restaurant next to me asked about it and we started talking.

They were both in Poprad on business for a supply company in a small town north of Prague. Petr was in his 30s, conservative looking with short hair and glasses.

Jana was one of those 50-year-old hard bodies with short blonde hair and a form-fitting, short, blue business suit. They talked about their love for the new Czech Republic, their life in rural Europe and and their visits to Prague.

Once again, I’m seeing Czechs swoon about their country, like they just bit into the best apple strudel of their lives.

Then they introduced me to another Czech tradition, one that sent my evening tailspinning into the bowels of road despair.

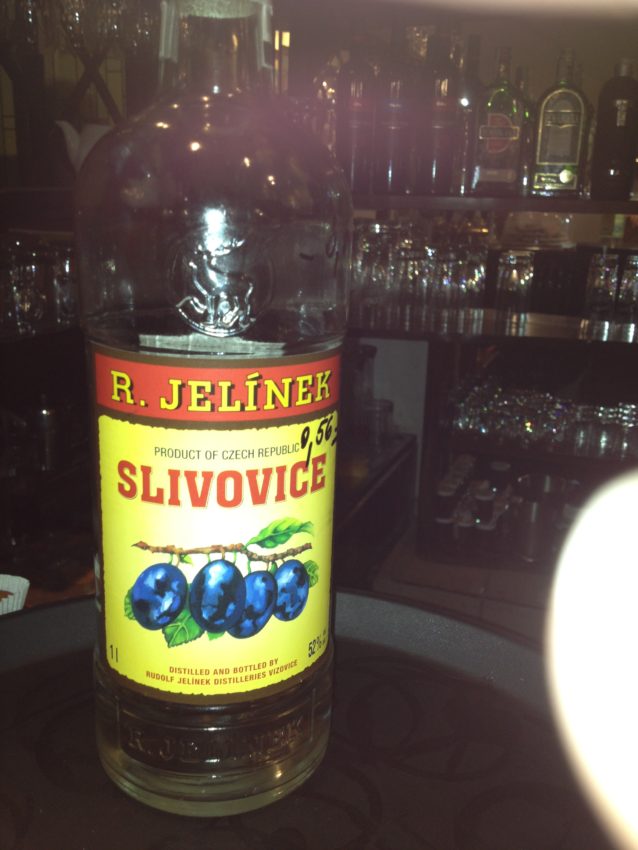

Slivovice.

Pronounced sliv-oh-VITZ-ah, it’s plum brandy, and the listed alcohol content of 50 percent is about as accurate as its health benefits. It dates back to the 16th century and during communism, it was apparently quite popular with the Soviet navy.

Not only was it a nice nightcap for sailors but in times of cutbacks, Slivovice is really good boat fuel.

The bartender brought it iced, by my request. As the three of us got down to some serious shots, I noticed the bartender gave me a knowing smirk. He knew something I didn’t. And it wasn’t because Slivovice is usually served at room temperature.

We said, “Na zdravi!” (Cheers!) more times than I can count in between stories of family (Jana has, shockingly, daughters 29 and 28 years old). Petr has no family and is an avid fisherman. His cell phone is filled with pictures of him holding fish of various sizes and degrees of ugliness. Soon, we were exchanging cards and they were inviting me to their little Czech town for a real Czech feast.

But, please, if they serve Slivovice, I will run to the German border.

The moment I laid down, my room started to spin like I was stuck inside a blender making margaritas in a biker bar near Juarez. I didn’t know what European historical period I was in.

If Stalin had marched Soviet troops into my room I would’ve gladly surrendered if he had a cure for the violent earthquake Slivovice put in my stomach and head. (A very under-appreciated amenity in my pension: The toilet can flush numerous times in two minutes. Think about it.)

So pulling a repeat in Bratislava wasn’t on my agenda last night. My hangover had mercilessly disappeared about halfway to town and an intense hunger replaced it. On the way into Bratislava’s Old Town, a found a sprawling outdoor tavern called Bumbalka.

It was filled with outdoor picnic tables and Budvar (Budweiser’s paternal father) signs. If they played country-western music instead of American oldies it would’ve passed for a great Texas BBQ joint. Instead, it was just an authentic little local watering hole with typically Slovak food.

Slovakia is dirt cheap. I haven’t paid more than 2.20 euros for a beer, never more than 5 euros for a meal. For 3.50 at Bumbalka, I had a bean soup, breaded chicken and a big pile of boiled potatoes. A Budvar (so good you wonder how American breweries screwed up Budweiser) was only 90 cents.

A stroll through Old Town made me glad I made this detour. I passed under a huge arch of Michael’s Gate, featuring a 14th century base and a pointy 18th century tower that looks like a witch’s loft.

Inside the gate, Old Town is a pedestrian-only collage of outdoor bars, restaurants and souvenir shops. It’s over-the-top touristy.

I saw at least four big tour groups, each with the leader speaking softly into a microphone in front while his legion of lemmings behind all listened on earphones. I saw “I (heart) Bratislava” T-shirts and Slovak national soccer jerseys, made of cheap, thin polyester — for 80 euros.

But Old Town is charming and the beer is cheap. I found a tiny outdoor cafe called U Wolkra on a quiet side street where I wrote postcards and was introduced to another terrific Slovak beer I couldn’t pronounce.

Saris (pronounced SHAR-ish) is a dark, chocolate-colored beer that’s almost as sweet as a Hershey bar with no aftertaste. It was 1.20. With the pretty blonde waitresses running around (it seems like all of Eastern Europe has kept the communist-era emphasis on fitness),

I can see why the region has replaced wheat in communism with tourism in capitalism as a chief source of income.

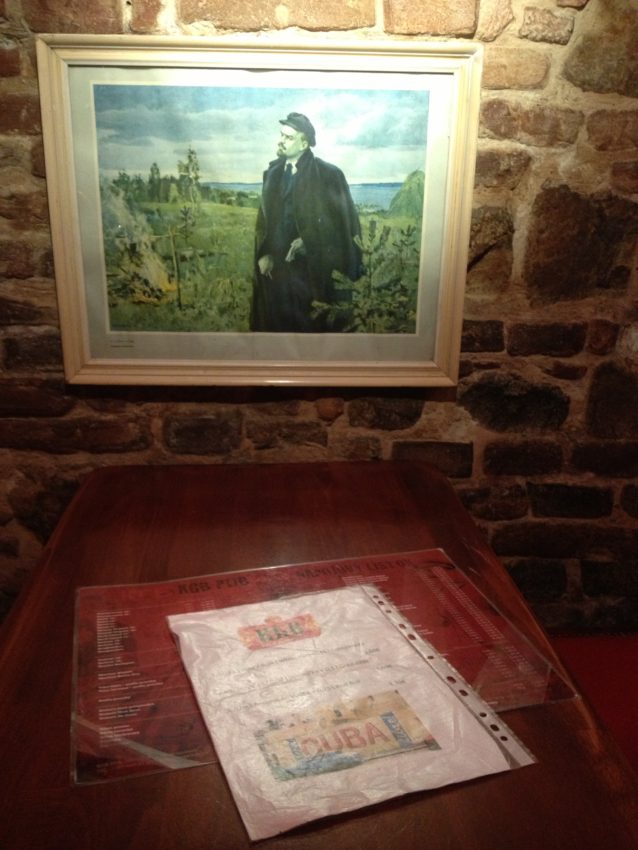

I had only one real must see in Bratislava. It was not the castle which dates to the 15th century but was rebuilt in the ‘50s and looks like a roller coaster is running through it. It was not the UFO-shaped TV tower that has the most overpriced restaurant in Eastern Europe. It was the KGB Bar.

It’s right on Obchobna, part of the main drag that leads from my apartment to Old Town. Its sign is of a peasant woman in a head scarf holding her index finger to her pursed lips. In other words, shut up and don’t look anywhere but in your beer.

The inside is a dedication to all things communist. The top shelf behind the bar is lined with busts of Lenin and Stalin. I nursed another tall Saris next to a giant Lenin statue which someone desecrated by doffing Vladimir’s mug with a red privateer’s hat.

Old black and white photos of Stalin and Lenin decorate the booths. An old manual typewriter that was probably used to send out communiques rested on the bar. USSR flags and hammer and sickles were everywhere. I loved it.

After Prague’s glitz, the Tatras’ glory and Bratislava’s cuteness, I finally got in touch with my inner Marxist.

I tried talking to the bartenders about what old Slovaks think about a bar glorifying a 45-year period of oppression. They looked so young, they probably thought Lenin is a goaltender in the NHL. They had no idea what I was talking about.

“It’s mostly for irony,” my train compartment companion said. “They’re making fun of it.”

I wondered if they have any “irony” bars in Alabama called the KKK bar.

I contemplated that as I had my last meal in Eastern Europe. I had to try Bryndzove’ halusky, Slovakia’s national dish. It’s potato dumplings covered in sheep cheese (bryndza) and bacon bits.

I’d seen it in the mountains huts and it looked like someone had cut open a sheep and poured whatever came out of the intestine onto a plate. It’s all lumps and fluids and bits of red.

But I went to the Slovak Pub, on the tourist trail but my AirBnB’s recommendation for the best Slovak food in town. It’s in an upstairs building just a few businesses down from KGB. Each room had its own theme dedicated to Slovak history.

I apparently sat in the Stur’s Room, dedicated to a group of 19th century intellectuals who collaborated with Lucovit Stur, a Slovak nationalist who revived the country in the 19th century, to codify Slovak orthography and make it into an official language.

My table was surrounded by portraits of his army, all looking very distinguished in black beards, moustaches and topcoats. A giant painting of Stur, brandishing a sword and wearing full military colors, was on the near wall.

Bryndzove halusky is the reason why I no longer judge taste by appearance. It was fantastic. They were small potato pieces, like mini gnocchi, with a sharp smoky cheese oozing all over it. The tiny bacon bits, some with a bit of fat, added just the right salty touch.

The restaurant has an organic farm in Stupava, near Bratislava, where they make the cheese and bake their own bread. A TV had a continuous loop showing how the cheese is made, interspersed with Slovaks doing a somewhat stilted rendition of traditional dance.

I’m dancing out of town. Two weeks in Eastern Europe and I’ve had enough beer, potatoes and goulash. I’m dying for a glass of wine and a pizza.

If someone offers me grappa, I’ll brain them.