Taj Mahal is the beautiful face of India but so are ugly Indian trains

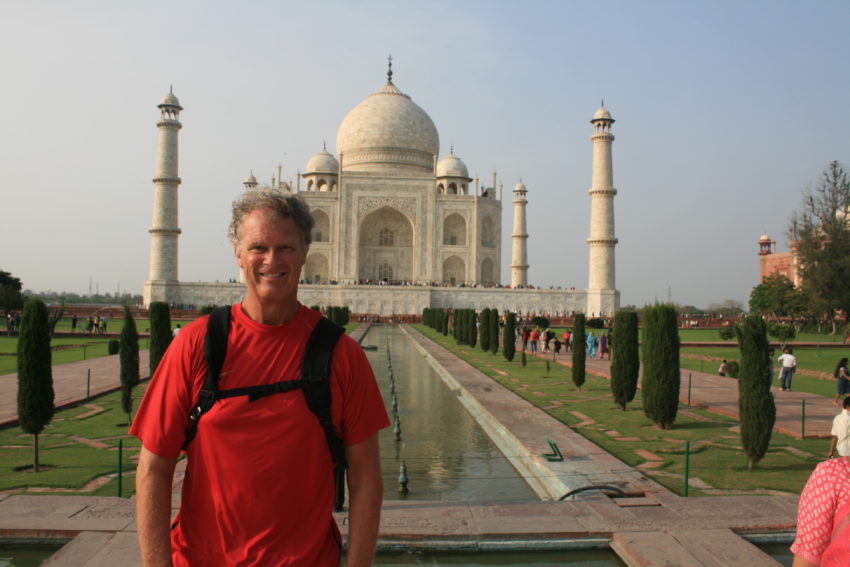

AGRA, India — It looks like a giant vanilla ice cream sundae when you first see it. It’s a great soft white dome surrounded by four smaller dollops. In the sun, they glitter. Or was that melting snow I saw?

I deny I’m making the association due to another tongue-swollen humid day in India. Delhi again was nice and cool. It wasn’t due to way too much time in India. Two weeks is a snapshot compared to the six, nine, 12 months the bedraggled, filthy Indiaphiles I saw tramping around on five euros a day.

It was due to one of the Seven Wonders of the World living up to its billing as the most beautiful building on earth. Eiffel Tower? Take a bow. Ever since I saw you stand over Paris like a Rockette on stage when I was a 22-year-old backpacker, you’ve been my No. 1 gal. Not now. Not after walking through a giant red sandstone gate which perfectly frames the Taj Mahal. It’s true, really. Every hardened traveler who treats crowds like immigration officials say pictures don’t do the “Taj” justice. It’s exactly as wide as it is tall, 55 meters x 55 meters. The four corner minarets make it look like a four-poster bed, providing a romantic image for a building built on love.

The Mughal emperor Shah Jahan built it as a mausoleum in honor of his third wife, Mumtaz Mahal (from whence the name comes) who died in 1631 while giving birth to their 14th child, (a death which, in my book, can’t be too surprising). It took him eight years to build it and the complex was completed in 1653. Jahan’s son, Aurangzeb, overthrew him and imprisoned him in nearby Agra Fort, a good example of India’s cutthroat politics not to mention an example of how your family tension isn’t all that bad. For the rest of the Shah’s life, the Taj Mahal tortured him, knowing he could do no more than look at the gift he gave his wife. After he died in 1666, he was buried in the Taj next to her.

After the train ride out here, I nearly asked if they had room for a third.

They say the Taj is just outside Delhi but it’s three hours away. That seems longer when you spend two of those hours standing up between train cars hoping one of the samosa vendors or giant bags of flour don’t knock you on to the garbage-strewn railroad tracks.

Along with the humidity and one bitchy Swede in Varkala, joining my list of negatives in India are Indian trains. I heard there’s something romantic about them. No question they are part of the fabric of Indian travel. They’re a rite of passage, if you will. You’re not a true Indiaphile unless you go a week without bathing then take a 24-hour train ride. It’s life among the masses. In India, masses takes a whole new definition. I have a new description.

Indian trains suck the great big green one.

I don’t know exactly what that means but it sounds pretty negative. I had a reader call me that once and I wondered if his level of hatred toward me matches my hatred for Indian trains. In truth, Indian trains are filthy, crowded, dark and spooky. Filled with sweaty arms, bodies hanging from shattered door frames and faces sticking through the blue metal bars covering the open windows, these trains look like they’re all headed to Auschwitz.

Indian trains are very confusing. The train stations seem like extensions of the cities. In Sri Lanka, stations look like time warps back to the British Empire. Station masters step out onto the platform in charming, white, pressed uniforms and blow a whistle. They’re right out of a Rudyard Kipling poem. Every station is neat and clean with clear destination signs. In India, they are slums. I walked into Agra’s train station and entire families slept under covers in the waiting lounge. Garbage littered the platform at Delhi’s Nizamuddin Station. In Agra, waiting for the train back to Delhi, rats — black, ugly, filthy, disease-carrying, vicious rats — scurried across the tracks, chasing any edible garbage people tossed through the windows. Indiaphiles want the true India?

Hang out in Agra’s train station.

Buying a ticket is like trying to find the right window in a game show. I didn’t know what I was getting. I counted six classifications: 1AC, 2AC, 3AC, chair car, sleeper car and general class. Everything but first class, chair car and sleeper are cheaper than a soda on Amtrak. My 2 ½-hour train ride from Alleppey to Kochi was $1.50. I bought a three-hour second-class ticket from Delhi to Agra for 85 rupees ($1.33). I tried asking the clerk what car I take but I could bare see him through the filthy glass window. I could barely hear due to him never turning my direction when he talked. Maybe he was beating away rats.

A couple of nice locals on the platform directed me to the Agra train and I sat in a sleeper car where I usually found myself on past trains. No one ever checked my ticket. No one seemed to care.

Keep in mind a sleeper car here isn’t like the Orient Express. No tuxedoed waiter knocked on my door to serve tea as I tucked myself under a comfy quilt on a cozy bunk bed. No. An Indian sleeper has small, steel platforms held to the wall by straps. Fans that apparently haven’t worked since Mahatma Gandhi rode around hung in the air behind wire cages. The car is lit like a prison cell. Slits of light burn through the windows between the iron bars. I saw no light bulbs anywhere.

Still, I found a comfortable bench next to an open window and tried to stay awake after getting three hours of sleep the night before. A family of seven, with three small children and two exhausted mothers in head scarves, eyed me curiously.

Suddenly, I was jostled awake by the first Indian train official I’d ever seen onboard. He carried a clipboard with dozens of pages, all showing lists. He took my ticket and started running his fingers up and down the sheets of paper. His bored expression never changed. I figured I was had. I thought of saying, “You won’t find me there” but instead I waited for the inevitable.

A bribe.

“Four hundred rupees,” he said. He should’ve had his hand out. Or a machete. I told him this is where they directed me. He sighed deeply and instead of further shaking me down, as how an Indonesian traffic cop did to me once, he gave me a go-away motion which I dejectedly took to the next car. However, iron bars blocked my path. Next to the locked door was a short, sharp-dressed man about 30 sitting on a pulled-out bench. He said his name was Marty.

“I was in the wrong car, too,” he said, like a kid sitting in the corner of the principal’s office. “We wait until the next stop and move to the next car.”

The “next car” was so packed, people hung out the door. I grabbed one rung of the ladder before the train started to pull away. Marty bulled his way through the crowd, creating a small opening for me to grab space between cars. An old, skinny woman with skin like cracked leather sat on two big bags of flour and looked at me with suspicion as if I was going to sneak one of the 25-kilo four sacks into my camera bag.

For the next two hours, this was my position. I shared space between railroad cars with 13 others. At least two dozen more were jammed into the corridor running along the compartment filled with dingy benches. I felt like I was on a flotilla. However, the passengers weren’t desperate and poor. They were all men, all in their 20s and 30s.

“I’ll do this for small journeys to save money,” said Marty who had a perpetual smile through the whole trip. “For more than three hours, I’ll get a reservation.”

Compounding the density were vendors squeezing through two dozen bodies shouting out their loot of peanuts or drinks long since gone warm and a sickly sugary Indian chunk candy that looked as if it was sweating. I had to bend inward to let them by while subtly touching my wallet to make sure they didn’t run off with the equivalent of their month’s salary. I had about $50.

After I inhaled to get more passengers in, a young guy with a pudgy face, glasses and easy going manner, turned to me and said with a smile, “India’s population is growing.”

Thank God I didn’t have to go to the bathroom. Thank God it was cool out. Thank God I only paid $1.33.

When we finally arrived in Agra, a taxi took me the three kilometers to the Taj Mahal grounds. I heard the biggest negative about visiting the Taj Mahal in Agra is having to visit Agra. It’s one of the vile hell holes in a country full of them. It does have a bevy of souvenir stands, around for decades to soak the 3 million annual tourists, twice Agra’s population. However, I found it aesthetically pleasing with its windy, narrow alleyways and smells of curry and coriander pouring out of little stalls. The streets form kind of a rat’s maze before spitting you out the other end where you get the big cheese: the Taj Mahal.

Visiting the Taj Mahal isn’t a spiritual experience like the Vatican or Himalayas. It’s a tomb, for God’s sake. What blows you back when you first walk through the archway is just its sheer, uncompromising, jaw-dropping beauty. It is spectacular. They say the white marble shines as the sun changes. Unfortunately, the sun wasn’t out. However, the Shah built it with the Yamuna River behind it and nothing else. The massive monument’s total background is a brilliant blue sky.

And the view got better as I approached.

In the foreground of the Taj is one huge, long, shallow pool filled with crystal-clear water. On a brilliant day, you can see the Taj’s reflection in it. A traveler’s Kodak moment is clicking a picture that shows the real Taj Mahal and below the exact mirror image in the water. I had no sun but the overcast day did nothing to spoil the sight of a building that moved 19th century Bengali writer Rabindranath Tagore to write, “The Taj Mahal rises above the banks of the river like a solitary tear suspended on the cheek of time.”

Once at the building, I noticed the brilliant detail that went into it. Most notable are what they call “pishtaqs.” They are arches on all four sides of the Taj. They provide depth. Each one is covered with a lattice marble screen that allows beautifully patterned light to illuminate the inside. The shadows look like Caravaggio paintings.

I stepped closer and rubbed my hand against the beautiful 400-year-old white marble. It felt like something Michelangelo would carve. Engraved in the marble are flowering plants which represent paradise. Going up the columns are Arabic calligraphy. The Islamic Mughai Empire ruled India from the 16th to the 18th century. In a spot of architectural and calligraphy brilliance, the letters get bigger as you look higher. Thus, all the letters look the same size from the naked eye below.

Then there is what they call the Pietra Dura. About 35 different precious and semiprecious stones created different colored flowers inlaid into the marble on the inside and outside of the walls.

Once inside, the Taj Mahal looks remarkably small. Except for the patterned shades of light coming through the lattice windows, it is pitch black. All that’s inside is what the Shah intended: two tombs, one of him and one of his wife. However, the tombs are fake. The real ones are buried in an underground vault and unavailable for viewing.

Unlike touring most world-renowned monuments, this time I didn’t want to leave. I wound my way through the dusty alleys and found myself in the middle of a small but wild Hindu festival. People with faces painted in a rainbow of colors were dancing and singing — and throwing colored dust at everyone within range. That included me. I walked up to the rooftop restaurant of the Saniya Palace Hotel covered in orange and green and red. I looked like a tie-dye shirt. Even my camera was orange.

I sat down on the roof with other tourists not caring that I could sprinkle red dust on their curry. I sat down and stared out at a gorgeous, rooftop vista of the Taj Mahal in the distance. The clouds prevented a sunset but you’d need a bomb to take away the view of this magnificent building. Conde Nast couldn’t have arranged for a better last day in South Asia for me. Here I sat, eating the best naan bread I’ve had in India, drinking my last ice-cold Kingfisher beer and staring out at the most beautiful building on earth. A muezzin’s call to prayer floated over the rooftops. The sky grew dark.

India’s locomotive economy is a beacon for critics and diplomats alike. The boom has both united the country and torn it apart, violence springing up as fast as high-rise condo buildings. I only saw a couple of the Indias. There are so many more to see in between the growingly wealthy upper castes and the expanding poverty. But India’s past is what will never change. A melting pot of religions, cultures and food has made India the mystery that it will remain forever.

The Taj Mahal is its face. Shah Jahan made it as beautiful as his wife. In every way it’s as beautiful as their country.

February 18, 2023 @ 9:00 am

Ah! John, that was a cool write-up on sleeper cabin. Always wondered about the conditions. Love that tired clipboard part. Guess Granny’s steel Depression-era fans in southwest Missouri weren’t so bad after all.