Another Earthquake hits Italy: A prime minister resigns and the EU nervously waits

I’d fall back on the cliche that Italian politics is like a TV soap opera. The only problem is TV soaps are much more believable. No one would write a script, even a documentary, about a country that has had 67 governments in 70 years. If anyone tried, they’d better have a good rewrite man.

Like now.

Prime minister Matteo Renzi’s resignation Monday following Sunday’s runaway defeat of his referendum has left Italy’s political future wildly up in the air. In Italian politics, that’s a little like saying the Ganges River is more filthy than usual. However, it’s true. Italy may be another domino that falls in the European Union, which is starting to reveal cracks like a windshield of a car driving through a war zone. A worldwide populist movement has led Spain and Greece to vote for new parties, Great Britain to leave the EU and the U.S. to elect Donald Trump. This next one in Italy could be Brexit with better food.

In the forefront is a man who’s been compared to Donald Trump. No, it’s not Silvio Berlusconi. This one’s a former comic. I’m serious. This is Italy. It’s European politics’ laugh track.

Italians, particularly here in Rome, are ecstatic. They know the alternative could be worse. First, a little explanation of what led to Renzi, like a defeated Roman soldier, falling on his sword: He wanted to pass his constitutional referendum in order to streamline a clogged Italian government that is more twisted than a blackberry bush. He wanted to make it easier to pass laws. Some politicians wanted him to win merely to make it easier to fire. As one legislator said, “We need to be able to fire people who sit in the office watching porn.”

Italians, however, trust Renzi about as much as Starbucks. They want nothing more to do with him. This is a peninsula that has suffered upheaval and political hacks for more than 2,000 years. Renzi was Italy’s third prime minister in three years and the next prime minister will be the fourth straight appointed and not elected. And it’s true. In 70 years, Italy has had 67 governments. Soon it will be No. 68.

At 39, Renzi became the youngest prime minister in Italy’s history. Young, energetic and handsome, the former Florence mayor and his center-left Democratic Party set out to reform a country still reeling from nine years of Berlusconi. Instead, over Renzi’s 2 ½-year tenure Italy has regressed.

Italy stands 80th in the Index of Economic Freedom, right behind Madagascar. Ten percent of southern Italy lives in poverty. As of February, unemployment was 11.7 percent, 40 percent for young adults.

Renzi’s referendum was more of a referendum on him than streamlining the government. He basically approached the Italian people as if they were a good-looking Italian babe in a club and said, “Would you like to dance?”

The people looked him up and down and said, “Sure. With who?”

Italians feared Renzi would have too much say. They saw it as the first step back toward Italy’s fascist roots where one man (See: Mussolini, Benito) could have absolute power. They wouldn’t be able to choose their representatives in Parliament. Bureaucrats would work merely to satisfy Renzi and not the needs of the people.

Sunday morning I joined my girlfriend, Marina, to the polls at her local elementary school. Marina is a highly educated, intelligent, liberal, independent career woman who won’t be told what to do. She said she was 100 percent voting No. She never wavered. During the last month, I didn’t meet a single Italian voting Yes. Then again, I never met anyone this fall who was going to vote for Trump, either. That tells you the left-wing crowd with whom I run.

No one danced in the streets Sunday. I saw no one weeping, from joy or sorrow. “NO” won by a 59-41 margin, an outcome as predictable as Italy vs. San Marino in soccer. In Sicily and Sardinia, more rural and poor, the margin of victory was about 45 percentage points.

The ramifications, however, are massive. Immediately, the euro dropped to a 20-month low before settling back at the usual $1.07. Italian banks are a shambles. Italy may have the best art, food and wine on the planet but its banking system is strictly Third World. Now it’s worse. Monte dei Paschi di Siena, the world’s oldest bank, had already lost 85 percent of its market capitalization this year. This week it dropped 4.2 percent more. That’s nothing. Stocks with Banca Popolare di Milano dropped 7.9 percent; Banco Popolare dropped 7.4.

Italy has Europe’s third largest economy but its 360-billion-euro debt, a third of the eurozone’s total debt, is the third largest public debt in the world. Even with the No victory, it’s an uneasy time to be an Italian. As La Repubblica wrote in an editorial, “Now the reality is the risk of a return to the swamp and to instability.”

Coming up will be a power grab that could change the future of Italy forever. There is pressure to move the scheduled 2018 prime minister election up a year. Some salivating parties want to move it up to, like, the next hour and a half. Leading the campaign is the relatively upstart 5 Star Movement, which wants to use the momentum from Sunday’s vote to move into power. They are in favor of breaking away from the European Union and even a possible return to the lire. Ask nearly any Italian how much good the 2002 switch to the euro has been for the country, and they roll their eyes, slap one hand on the other arm and shove their fist up into an imaginary body cavity. It has been a disaster.

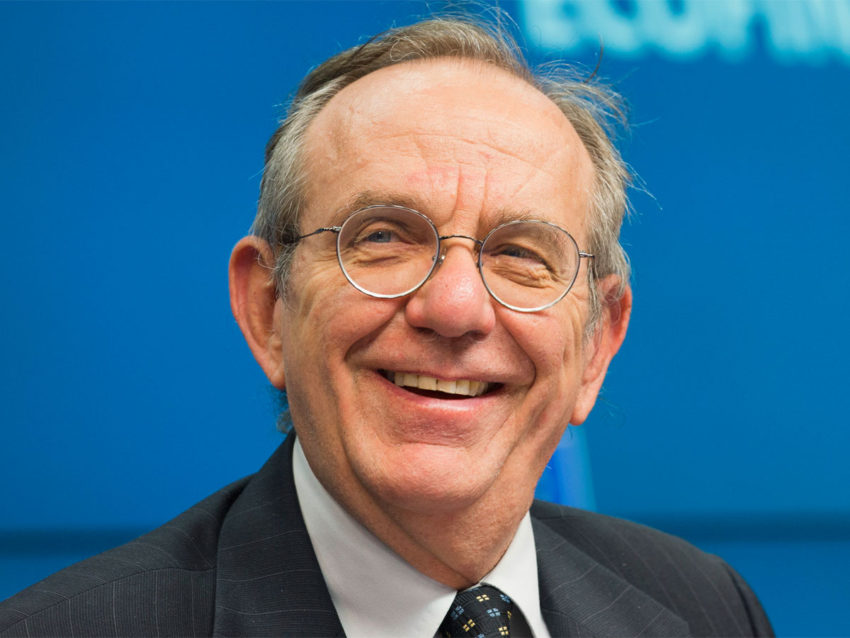

Italy’s mainstream parties want to stop the 5SM but don’t know how. According to bookmakers, the smart money is on finance minister Pier Carlo Padoan with anti-mafia prosecutor Pietro Grasso running second.

Leading the 5 Star Movement is Beppe Grillo, 68, a former comedian with wild, gray hair who pushes for leaving the EU in every one of his bombastic public, outdoor speeches. He won’t become prime minister. However, he may have a big say in who becomes the next one.

So I now live in a country that’s become more unstable than the one I left. After Nov. 8, I didn’t think that was possible. But in Italian politics, anything is possible. Italian is a difficult language. But everyone in the EU knows one Italian word.

Arrivederci.

December 7, 2016 @ 8:02 am

Interesting – been reading about this but only via American news publications. Interesting to read observations from someone on the inside.

December 7, 2016 @ 10:49 am

Craig: I’m not really on the inside of Parliament, just inside my Italian friends’ heads.

December 9, 2016 @ 8:51 am

I did a lot of research before I voted no. Even though I agreed with a lot of the things Renzi wanted to change, I wasn’t comfortable with a lot of the details. Mannaggia!

December 9, 2016 @ 9:35 pm

I don’t know how I would’ve voted. Italy is so screwed up, it needs change. But apparently the people in Rome didn’t have enough faith in Renzi to change them correctly.

December 10, 2016 @ 3:29 pm

The reforms were rejected simply because they were simply awful: power transfer from local entities to the central government, shorter time for parliament to vote on and amend government-proposed legislation, and the EU would have been mentioned 12 times in the Constitution. Surely the fact that Renzi promised to resign in case of loss added an incentive for all of his opponents, but that wasn’t necessarily the main reason of the victory of the No campaign.

I also think that the Italians showed spine in this referendum, because media, corporations, bankers, etc… tried to terrify them by saying that the economy would collapse if reforms didn’t pass, they would lose their savings, etc….

Well, guess what: Italians voted No anyways, and for some strange reason the Italian stock exchange has just had one of the best weeks in years (the FTSEMIB index increased by 7% this week).

As for government “stability”, Italy has never really had it since Fascism: more than 50 prime ministers in 71 years!

And this permanent “instability” has no correlation to economic growth at all, because Italian executive cabinets used to change very often also when the economy was booming, from the ’50s to the early ’90s.

All in all, the result was the best outcome for Italy and the Italian people. Not really for some politicians, bankers, lobbyists, and Bruxelles’ bureaucrats instead.

December 11, 2016 @ 3:14 am

Great analysis, Marcello. I agree with your points, some of which I didn’t know about. My girlfriend didn’t mention anything about scare tactics. Maybe it’s because, like the other Italians, she ignored them.

December 14, 2016 @ 12:58 pm

I voted No here from Chicago, for the same reasons mentioned above in the OP and replies.

As for Lire to Euro, my family in Italy said that move cost the people 2,000 Lire for 1 Euro, effectively impoverishing them, an event they never recovered from.

If Italy changes the money again, it could be another opportunity for further impoverishment!

December 14, 2016 @ 2:53 pm

Sandra, a proper reply to you should come from an economics, which I am not. So I’ll take your word for it.