Growing old and blind in Rome: My venture into Italy’s No. 2-ranked public health care system

As the United States free falls into Donald Trump’s Let-Them-Eat-Cake health care plan, I am learning first hand the benefits of the health care American progressives dream about. It’s not by choice. It’s not by journalistic research. Instead, for the past two months I have had an inside look at Italy’s public health care through my own misfortune.

I am now half blind.

My right eye has gone from near 20-20 to non functioning. If I close my left eye, it’s like a steel door covers my right eye with slits to let in some light. I’m a prisoner in my own skull. My depth perception is shot. Most everything is blurry as if scuba diving without a mask. This didn’t happen gradually. It happened nearly overnight. And it’s frightening.

It’s frightening, at 61 years old, for the first time in my life, to feel old.

The bad news is my Indianapolis-based insurance company doesn’t cover vision; the good news is I live in what is ranked as the healthiest country in the world with public health care ranked No. 2 in the world. That has allowed me to get excellent treatment at a low cost. If this had happened in the U.S. without insurance, I’d be homeless.

It all began the first week in May. I went to a sports event and couldn’t tell the players’ numbers apart. I was a sportswriter for 40 years. I’ve been in stadium press boxes stuck so high seagulls looked up at me. I only needed binoculars to see coaches’ facial expressions during crunch time.

I figured I had an eyebrow hair in my eye. I’ve been accused of having bushier eyebrows than Groucho Marx. I went home and washed my face. Nope. The upper half of my right eye remained blurry.

I didn’t panic. I could still see well enough. But curiosity hit me. What the hell happened? I told Marina, my angelic Roman girlfriend, who directed me to Ospedale Monospecialistico Oftalmico, a public clinic in Prati, my old neighborhood near the Vatican. They quickly saw me, examined my eyes and ruled out the dangerous detached retina. They diagnosed it as a disease of the optic nerve and that it wouldn’t get worse. I asked the clinic how much the visit and exam would cost. I braced for the answer.

“Nothing,” the doctor said with a chuckle. “This is Italy.”

Just to make sure the diagnosis was correct, they sent me to a neurologist at Azienda Ospedaliera San Camillo Forlanini, a massive public hospital across the Tiber River from me. San Camillo was built in 1929 and shows every year inside its yellow walls. Its hallways are dark. Its lower floors are dingy. Plastic chairs line the long hallway where I waited in its optic center with a crowd of people wearing eye patches, carrying canes, rolling in wheelchairs. We were all seen within 30 minutes. They put me through a series of tests. I read an eye chart. They dilated my eyes. I looked into a machine where I hit a clicker every time I saw a light flash.

They also diagnosed it as an optic nerve problem and handed me a prescription for some medicine. They did not hand me a bill. I was in and out of there in less than an hour. Total cost: zero. In the U.S., I’d have a sign reading, “I’LL WRITE FOR FOOD.”

I took the medicine and went on with my life. They were right. My eye didn’t get worse. My sight adjusted. After a couple weeks, I forgot I had the problem. I flew to Iceland and drove around the country for eight days, negotiating some uphill gravel roads in the rain and mud that required steel nerves not to mention keen eyesight. The only problem I had with my eyesight was I saw Iceland’s larcenous prices all too well.

After returning, I took Marina to Berlin for her birthday early last month and the following weekend we went to Paris on assignment. I woke up that Sunday in our lovely room in the Latin Quarter with the four-poster bed and the croissants waiting for us at our corner cafe. One problem.

I couldn’t see out of my right eye.

The lower half of my eye had joined the protest. My whole eye was blurry. It did get worse. What is happening? I’m going blind. This can’t be happening. I haven’t seen the Maldives Islands yet.

Marina laid out a few options for me and we completed our assignment without problem then enjoyed Paris the rest of the day. My good left eye allowed me to negotiate the streets without getting hit by a cab.

After returning to Rome that night, I returned to San Camillo the next day. I gave the neurologist an update. She threw up her hands and said, “I don’t know what happened. Somehow it got worse.”

Gee. Thanks.

I walked out thinking, Well, maybe in public health care you get what you pay for.

Clearly, I needed help. I couldn’t see and my depth perception had become problematic. In the gym, I totally whiffed at the weight rack and dropped a 26-kilo dumbbell on the floor. I tried putting a scoop of protein powder in my blender and poured it on my wrist instead.

I can’t live like this.

I called my dentist, a U.S.-trained Italian with connections in Rome’s medical scene. He hooked me up with a learned optometrist who works with expats at the Food & Agricultural Organization. He told me to go to Policlinico, another citadel-like public hospital associated with the University of Sapienza Roma. After one eye test, the doctor had a new diagnosis.

Congenital cataracts.

The good news is they can be corrected with laser surgery, and it’s free in Italy; the bad news is the wait can be up to eight months. I can’t wait that long. If I go to a private clinic, I can do it earlier but it’ll cost about 1,000 euros. I called my insurance company in Indianapolis, International Medical Group, if they cover laser surgery.

Sorry, they said. We don’t cover visual or dental.

“What? I’m half blind!”

“Sorry.”

“Well, what do you cover for the $1,800 a year I pay? Partial decapitation and Stage 5 cancer?”

He didn’t laugh. Then again, neither did I.

I took the Policlinico report back to San Camillo and that’s when I saw a flaw in more than just the Italian public health care’s decor. One arm doesn’t know what the other arm is doing. Either that or doctors enjoy finding folly in others’ analyses. Another neurologist looked at the report about cataracts and laughed.

“Yes, you have cataracts,” he said, shaking his head. “But he didn’t mention the optic nerve problem. That’s your big problem.”

He explained that cataract surgery will only help a little, not enough to make much of a difference. We did new tests and I flunked everything. He covered my good left eye and asked me to read the top line of the eye chart, the line with letters the size you see on STOP signs.

“What chart?” I said.

“How many fingers am I holding up?” he asked.

“I can’t even see your arm.”

They eventually told me I had something called Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy (AION). It’s congenital. It’s irreversible. It’s incurable. I went home and read up on the Internet. It’s all true.

I’m blind in my right eye for life.

However, I had one hope left. During my many tests, they once placed a lens in front of my “good” left eye. I say “good” only in relative terms. The last time I had it checked about 10 years ago it was about 20-100. However, with the lens, I saw much better. I not only could I read the top line of the eye chart, I could read the line second from the bottom. I could practically read the fine print on a pill bottle from across the room. I saw an optometrist at San Camillo who gave me a prescription for — God forbid — glasses.

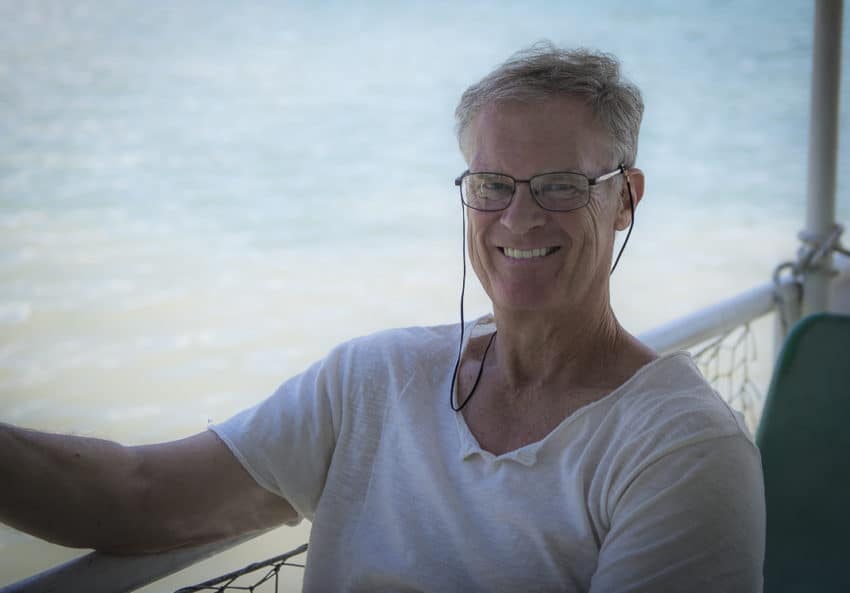

So on July 1, 2017, at 61 years of age, I put on glasses for the first time. I barely recognized myself. The lens I carefully chose made me look like the geeky dad in “American Pie.” Marina said I look more distinguished. She wins. I read somewhere that women like “a hot guy reading a book.” Unfortunately, I’ve only got the glasses and the book.

Still, the glasses re-opened my world. Most of my depth perception is back. I can drive. I can hike. I can see faces clearly. However, they’re designed for distances. Everything up close is blurrier than before. Thus, I have a black string on the back so I can take them on and off without misplacing them. It just ratcheted me up on the nerd meter.

Thanks to Marina, I still may have another chance. She did some research and found a private hospital that specializes in optic nerve disease research. She scheduled an appointment at Universita’ Campus Bio-Medico. Built in 1993, it’s what a private hospital in the U.S. would look like. Big glass windows,, huge lobbies, modern stairwells, comfy furniture. Stepping off the public dole, I had to pay 132 euros for the visit, still a bargain for an educated second opinion from a research hospital.

The doctor looked at my paperwork and was astonished that no one gave me a magnetic resonance imagery test. He gave me a prescription for something called Neukron Ofta Fiace which he says “should” help my right eye.

So I’m scheduling an MRI. I’m scheduling cataract surgery. I’m taking the medicine.

And I’m spending little. After two months of hospital visits, here is my cost list:

7 eye tests and hospital/clinic visits: 223.06 euros

Medicine: 102.26

Glasses: 99.00

TOTAL: 424.32 euros

Based on average prices found on medical websites, here are the projected costs if done in the U.S:

7 eye tests: $1,908

Medicine: $306

Glasses: $60

TOTAL: $2,274

I also just recently scheduled an MRI at San Raffaele Pisana, another public hospital, for Monday. Cost: 227 euros. The current cost of an MRI in the U.S., according to VOX Media, is $1,119. While I pay nothing for cataract surgery in Rome, it costs a staggering $3,530 in the U.S.

It all points to the absurdity of the American medical system. According to the World Health Organization, Italy has the No. 2 public health care in the world behind France. The U.S. is ranked 37th. According to the Bloomberg Global Health Index, which takes in life expectancy, causes of death, health risks and clean water, Italy is the healthiest country in the world, just ahead of Iceland. The U.S. is 34th. This is despite the U.S., through Obamacare, spending 17 percent of its Gross Domestic Product on health care, by far the most in the industrialized world.

Italy does have private insurance, which cuts wait time on surgeries and includes other benefits. However, only a minority of the population has it as the public health care is so good. Prescriptions are heavily subsidized and many consultations and exams, as I saw first hand, are free.

The million-dollar question, however, is something I can’t answer. Has Italy’s public health care helped me more than medical care in the U.S. would? I’m still blind in my right eye. I have no idea if it’ll get better. With the current medicine and future procedures, I’m told my eyesight will improve.

I don’t know if U.S. doctors would’ve diagnosed anything different. Despite the high costs, American medical care isn’t always what Hippocrates had in mind when he wrote that oath under the tree in Greece. At Kaiser, the huge hospital chain where I went with my company’s insurance in Denver, they twice mid-diagnosed injuries. Doctors said I needed knee surgery after hurting it jogging and surgery to repair a hernia after too much stress in the gym. I went out to get second opinions. Two physical therapy sessions with Mark Plaatjes, the former South African world marathon champion in Boulder, made my knee 100 percent. A surgeon, also at Kaiser, said my hernia wasn’t big enough to require surgery and it will work its way out. Which it did.

(A funny side note. When the surgeon, a female, examined my hernia, I dropped my pants. She looked at it and said, “Too small.” I said, “I BEG your pardon?” She said, “Your hernia. IT’S too small.” She wasn’t laughing, either. People in the medical field never do.)

From afar I’m watching my home country fight over the seemingly obvious dilemma of helping people who can’t help themselves. The rest of the world looks at Donald Trump, who is calling health care a product and not a basic right, whose proposal will eliminate health insurance for 20 million people, and rightfully see us as the most selfish country on the planet. The U.S. is a nation with the world’s strongest economy yet we can’t help our sick. It’s a shameful legacy and no one should be proud of it.

Even I can see that.

July 7, 2017 @ 9:22 am

We had terrific experiences with healthcare in Italy. It is one of the positive aspects of our life there that I miss. We were not on the national health plan since we weren’t on a permesso that long (several years as US embassy employees), but our private U.S. insurance kicked in and covered most everything we needed. No doubt the insurer was delighted since Italian doctors’ fees are so modest by comparison. Although our insurance still serves us well in the U.S., we can see the fees for services are insane here. What a racket! And in Italy we had quality time with doctors, not the 15-minut bites one gets in the U.S. We have joked about setting up annual appointments with our doctors in Italy and just making an annual trip for medical purposes.

Interestingly dental services were more expensive in Italy. No deals there.

July 15, 2017 @ 8:20 am

good luck with your eye

July 7, 2017 @ 9:38 am

Getting older sucks…but look on the bright side, you can still see and your hernia is “too small.” Good luck with everything!!

July 7, 2017 @ 9:53 am

“Insightful” article, thank you for sharing. I too have had varied healthcare experiences while living in Italy….however the same is true relative to my experiences in the US…at an exceptionally higher cost. As is true everywhere, we must research extensively and be educated consumers, especially with our healthcare!

Wishing you much luck in the search for the right team of professionals to aid you with your vision.

in bocca al lupo~

nml

July 7, 2017 @ 12:57 pm

Ciao John,

I had heart palpitations just reading about the scare with your eye! I’m happy to hear you are getting some answers. It’s not surprising your U.S.-based insurance doesn’t cover what you need. (Curious, after being a resident for the past few years, why do you carry U.S. based insurance?) I think that MRI estimate is conservative – about 1/2 of what I’ve seen. Your glasses look great!

July 9, 2017 @ 12:38 pm

From 2004 to 2014 we lived in Malta, Sicily and then Portugal. We are moving back to Portugal to retire as soon as our house in Virginia sells. I could write a book about my experiences in the healthcare systems of the above as well as Germany. I had a spinal cord injury that could’ve/maybe should’ve made me quadriplegic in 1983. It was misdiagnosed here in the US for 15 years despite seeing a small army of specialists over that time who regularly insulted me, ignored me or gave me the brush off. No one ever took an x-ray or did an MRI in those 15 years. I ended up having 2 spinal surgeries, one in Virginia in 1998 and one in Munich in 2007. Because of the delay I have serious, permanent neurological damage. The experience was like night and day. In my opinion the US system is a thinly disguised form of racketeering. I will be 60 this year. There is only one participating insurance company in the area. 90% of the medical care in central Virginia is through the university of Virginia system. Our insurer informed me that they will no longer cover ANYTHING that is through the U VA system and that next year our policy, (for 2), will cost somewhere in the neighborhood of $24,000 a year with a $10,000 deductible each. In 2014 I had 2 MRI’s in Evora, Portugal. 1 for my spine and one for my brain. I had private insurance through AXA, London that paid for both and the private hospital that I went to gave me a discount for getting 2! 175 Euros each. A regular blood test at the same private hospital, a complete metabolic panel with lipid and hormone screening is 60 euros. Last year here in the US the same exact test was billed to my insurance company for $2,000. It’s criminal. (Your glasses are awesome).

July 10, 2017 @ 1:37 am

Racketeering? Great comparison. I always wondered why so many people have so many of the same surgeries on the same body part. Don’t they ever get it right the first time? Or, as you suggest, they just leave a little left undone so they can go back in again? Your anecdotes were fantastic. Thanks. I hope a lot of people read them.

July 15, 2017 @ 8:55 am

I’m just curious: Are you officially an Italian citizen? Can any American simply move to Italy and get access to the Italian health care system?

July 15, 2017 @ 10:57 am

I’m not an Italian citizen. I don’t even have an official resident’s card. All I have is a Permesso di Soggiorno, which is permission to stay in Italy. I have to renew it every one or two years. I was as surprised as you are that I had access to the system. However, Italians with family doctors pay less for medicine and other services. I plan on getting my own family doctor Jan. 1.

July 10, 2017 @ 5:13 am

Thanks John,

The surgery in 1998 was indeed not complete. I made some calls to the University of Virginia hospital administration office and the neurosurgeon’s office and pushed for answers. Among my questions were why after a difficult 5 hour surgery that ended at 10PM they tried to throw me out of the hospital at 6 AM the next morning. (I managed to hold them off until 9 AM) I had to push hard but I finally spoke, off the record, with a billing nurse who told me that the insurance company insisted they do a “quick and dirty” and get me out of the hospital before the bill went up. In 2007 I was fortunate to have a referral from a very good Maltese surgeon, who looked at my MRI which showed my spinal canal in my neck was at that point 90% compressed and the cerebral spinal fluid was not able to pass the block, and he called Munich and set me up with one of the finest neurosurgeons in the world. In Munich I was in the private hospital wing, they were extremely thorough, the room was like a 5 star hotel, and it was a suite so my wife could stay next door in a beautiful room with a stocked mini fridge and, essentially room service. The surgeons operating equipment was made for him personally by the medical division at Carl Zeiss optics. It allowed him to operate down to 1/10,000th of an inch accuracy. They kept me for a week after the operation. They wanted to keep me for 3 weeks but it was olive harvest in Sicily and we needed to get back to our farm. The entire cost was paid by AXA insurance, London. The cost was 19,000 Euros. I have been told that here in the USA it would have been more than 100,000 dollars.

July 10, 2017 @ 6:10 am

Amazing recovery story, Christopher! The Munich hospital sounds remarkable. How’d you find out about AXA insurance in London and how much is it a year? I may not re-up with International Medical Group. Also, how much good did the operation do? You said you still have pain?

July 10, 2017 @ 8:04 am

John,

When we were living in Malta we needed private insurance and the best fit for us was Atlas Insurance. When we moved to Sicily we needed to replace that coverage and it turned out that Atlas was a part of AXA so I looked up AXA online and found their PPP International cover. It was great insurance and because we had not lapsed in coverage they did not hit me with a pre-existing clause. In fact the operation in Munich was only about 6 months after we started with AXA. Back then you could choose the Europe only cover and for the 2 of us it started out at around $1,500 each, no deductibles, very little co-pay and for most things 100% cover. When we came back to the US in 2014 it had increased to about $3,000 each. I would look them up online and then give them a call.

The surgery in Munich saved my life. There are still a lot of muscle spasms and the last 10 years or so it’s obvious that there is also autonomic damage which is frankly quite challenging to live with. It’s kind of an ambulatory quadriplegia which has a lot of overlaps with the shock wave damage that football players suffer from. One appears quite healthy and fit but the truth is something else.

September 16, 2017 @ 11:15 pm

hi…enjoyed the post on the young pope as an extra. just watched the whole thing. beautiful.

re: your eyes. there is an herb. Triphala…actually 3 herbs in one. can get it online at http://vadikherbs.com/?s=triphala&lang=en. take a teaspoon or less, soak in water overnight. then rinse eyes w it in am (some strain the liquid, or just spoon it out – may want to use one of those eye cups). also useful, yoga or whatever to invert oneself – have blood run to the head. it gets the blood to the eyes. even one week of inverted for 13 min….building up to that amount over a few days will make a marked improvement in the eyes.

September 16, 2017 @ 11:17 pm

eyes: https://lifespa.com/home-ayurvedic-eye-treatment-ghee-netra-tarpana/ – another option. May you see better very soon. Pray for eye healing-the attention on the eyes will help.

June 25, 2024 @ 11:32 am

Have been there. I became totally blind in my right eye after a misdiagnosis in a Rome clinic ( was sent there with a ” raccomandazione” not always the best outcome) I researched eye surgeons in Rome and found one in the Gemelli Hospital that inspired confidence. He diagnosed a severe cataract that had calcified and was removable. Programmed free surgery, in 2 months all done, sight restored and as my other eye was also showing opacity he decided to programme that surgery as well as my cataracts were induced by medication of cortisone over a long period of time. Second eye done, again at no cost. They have discovered macular degeneration which is still under control and he was positive about the way we will face it when the time comes. I only paid for the initial consultation as I wanted to see him specifically so paid the ” intrameonia cost in the Gemelli of €150 and of course the various optical drops after surgery. Have lived in Italy for 50 years and have always had excellent medical care. Best of luck with your eye journey

June 25, 2024 @ 11:07 pm

What a great, inspiring story, Helen. Thank you. I hope all opponents of Obamacare read it, too.