Bilbao: Guggenheim puts Basque capital on world stage

BILBAO, Spain – The giant curlycue sculptures stand like unraveled spools of steel fallen from a space station. I walked through the increasingly tight circular pathways inside the sculptures and lost my sense of space. The mazes, with the steel sheets more than twice my height, weren’t claustrophobic. On the contrary, they opened up my feelings of space and time.

American architect Richard Serra called his sculpture The Matter of Time because, he wrote, “… it is based on the idea of multiple or layered temporalities.”

I’ll put it in layman’s terms. The star permanent exhibit of the world renowned Guggenheim Museum is a symbol of the city that it helped make famous. Bilbao, Spain, the capital of the fierce Basque Country, is all about layered temporalities, of transformation, of losing yourself in space and time.

Outside the famed titanium architecture of the Guggen, as the locals call it, is a long, green, tree-lined walkway along a river, an old town that takes you back to a time of fierce independence, a city that has gone from a gray, industrial pit to one of the most vibrant destinations in Europe.

Picture Pittsburgh circa 1965 and you have Bilbao before the 1990s. Picture a city dripping with culture, of locals fishing in a cleaned-up river and award-winning architecture and you have Bilbao today. After only four days, it became my favorite city in Spain.

Why Bilbao?

I came here for the annual October meeting of my Mediterranean Chapter of the Travelers’ Century Club (TCC), an international group of travelers who’ve been to at least 100 countries and territories. These people have been everywhere. Some have been to every country in the Americas. Others have gone into Afghanistan. Sit in on discussions and they swap tales of border crossings in Sub-Saharan Africa.

But they haven’t been to many cities that have changed its public face as much as Bilbao. The world has noticed. To wit:

- In 2010 Bilbao won the Singapore-based Lee Kuan Yew World City Prize, the Nobel Prize of urbanism.

- In 2012, then-Mayor Inaki Azkouna received the World Mayor Prize awarded every two years by the City Mayors Foundation for urban transformation.

- In 2018, it was awarded Best European City at the Urbanism Awards run by the Academy of Urbanism.

Irala

I fell for Bilbao shortly after Marina and I checked into our hotel. The oddly named Hotel Bed4U, a Spanish chain, is in the Irala neighborhood. Out of the hotel we walked up the hill past a small playground to rows of streets lined with beautiful English-style houses sporting bay windows and rainbow colors. Red. Blue. Brown. Green. Yellow. Turquoise. White. Orange.

Juan Jose Irala grew up in the neighborhood in the early 20th century. He built a flour factory in the zone and it became so successful, the neighborhood became a city within a city with banks, schools, social centers, grocery stores and a tram line.

The neighborhood’s number of residents grew from 200 to 3,000 and was named after him. Today, it’s a magnet for world photographers and thirsty visitors who flock to Avenida Reyes Catolicos, a pedestrian street lined with rough-and-tumble bars and outdoor tables.

We took a seat at Estenaga’s horseshoe bar near a table where old men played cards under the green, red and white striped Basque flag emblazoned with the logo of Athletic Club, the famous local pro soccer team. I ordered a glass of a Basque red wine called Cune for all of €1.90 and basked in Basque culture that modern transformation will never forget.

Casco Viejo

You can also see it in Casco Viejo, the old town where its original seven streets date back to the 1400s. We strolled 20 minutes from the hotel and outside the 13th century Catedral de Santiago, with its beautiful Renaissance portico, we saw Bilbao’s modern transformation. The pedestrian streets were lined with modern retail shops that could be in any city in the western world.

But when I looked closer, I could see old Bilbao. Inside the ham shop called Viandes, I saw a dozen giant ham shanks hanging from the ceiling and a dark-complected woman standing nearby sharpening a knife that could fillet a brontosaurus.

We returned to the main drag by the river and entered a long boardwalk. We passed a long open-air vegetable and fruit market with mountains of lettuce and tomatoes. One entire table was covered with big apple pies. Another sported cheeses of various shapes and aromas.

Towering maple and palm trees covered the boardwalk. It looked like a romantic avenue in Paris. Joggers cruised by us. People sat on the plethora of benches and looked out at the river Nervion despite a cold, gray, drizzly day in the 50s.

We passed the Teatro Arriaga, built in 1890 with a beautiful gold and white Baroque facade and carved masks over the doors. Beyond that stood the 19th Bilbao City Hall with its big statues flanking the sweeping staircase.

Across the street stood statuesque brick apartment houses with planters full of flowers on balconies and sweeping views of the river and, also, the Guggenheim.

The Guggenheim

You can’t miss the Guggen.It’s as famous for its outside as it is the inside. Built in 1997 and designed by Canadian-American architect Frank Gehry at a cost of $97 million, the museum looks like a giant prehistoric sea creature from the outside. Titanium plates, looking like giant fish scales, stack on top of each other on the banks of the river.

Part of the motivation was to spruce up Bilbao’s decrepit port area. Mission accomplished. The Guggenheim attracts 1.3 million visitors a year, officially moving Bilbao into the forefront of the 21st century. Tourism has skyrocketed. Bilbao had 992,000 visitors in 2019. In 1995, it had only 25,000.

Consequently, metro Bilbao’s annual GDP is €30,860, higher than than the rest of the European Union and Spain.

Walking inside at Guggenheim’s ground floor, I looked up and saw three floors, curving around at odd angles. It definitely gave a dizzying illusion. Some critics, however, have said the Guggenheim is more famous for its architecture than its contents.

Let’s say it’s an acquired taste. Besides The Matter of Time, I went upstairs and saw what can only be described as a giant badminton bird. Called Soft Shuttlecock, it is splayed on the floor and made from canvas, latex paint and expanded polyurethane foam.

Then there’s the Atom Series, a group of op-art paintings of atoms that range from the image of pyramids to almost an exact aerial view of my University of Oregon’s football stadium.

The Guggenheim isn’t for everybody, but it’s definitely for the Basque people who have embraced it as their vehicle to the world stage.

“It’s like a symbol for us,” said Ricardo Hernani, one of the TCC members and a Bilbao native. “It has attracted tourism. We have something to show. It’s not an industrial city. It was turning into Poland or Slovakia 20-30 years ago.”

Basque pride

The 56-year-old Ricardo was talking in the Guggenheim’s spacious cafe. He has the compact, wiry frame of a mountain climber, which he is every weekend in the two small mountain ranges that frame Bilbao. He has climbed all over the world and leads numerous hiking and climbing expeditions.

More than a mountain climber or an engineer, he is Basque. According to the Bilbao city government, 51 percent of the city’s population of 356,000 speak some Basque language. Twenty-nine percent are classified as fluent. Basque is easy to identify. Every word seems to have an “x” in it.

Ricardo is fluent, and there is no subject he is more loquacious about than Basque culture. He proudly talks about his time on the board of Athletic Club, a team so Basque that every player must be Basque or have a strong connection to Basque Country. Despite a pool of only 2.2 million people, Athletic has won La Liga, one of the four top leagues in the world, eight times.

But the Basques have a tortured history. They have inhabited this section of northern Spain since Roman times. They remained independent from Spain and across the Pyrenees in France until the French Revolution in 1790 when they lost their institutions and laws.

Under Francisco Franco’s brutal rule from 1936-1975, he banned the Basque language and culture and political organizations. Any Basque who rose up he killed, tortured or imprisoned.

Ricardo said his father could not speak Spanish as a child and was hit in school when he spoke Basque. Basque names were forbidden. Tombstones with Basque names were destroyed.

The drive for independence still simmers. The Basque National Liberation Movement, known as the ETA and founded in 1959, had armed conflicts with Spanish and French authorities up until 2011. Ricardo is on the side of independence.

“It’s the best way to keep our culture,” he said. “Of course we had violence. People here want independence because in Spain, there are too many people who are far right. They don’t like that we can be different in the same country.

“Then in the end, if there’s an action, there’s a reaction.”

But the Basque culture seems to thrive in Bilbao. In fact, in the Basque Country’s last elections, 75 percent elected to Parliament were Basque nationals and 25 percent to Spanish parties. Basque Country is the only region in Europe that collects its own taxes and gives to the national government.

“We rule ourselves,” Ricardo said. “Politics in Madrid are even worse than here. I don’t know why. Politics everywhere in the world is getting worse, since (Donald) Trump and (Jair) Bolsonaro and all these guys are saying ‘You are stupid” and all this. Because we suffered through 40 years of violence, things are more stable here.”

If things are so stable, I asked, why do you need independence?

“Who will rule Spain in 30 years?” he asked. “Then it could happen again.”

San Juan de Gaztelugatxe

One day, Ricardo took me to the other area’s major attraction in the area. Since I’m the only person on the planet who never watched Game of Thrones, the 45-minute drive north to visit San Juan de Gaztelugatxe was not a pilgrimage. It is a stone hermitage dedicated to John the Baptist dating back to the 9th century atop an islet off the Bay of Biscay.

Game of Thrones used the islet for Dragonstone, whatever that is, with a digitally created castle replacing the medieval structure. We met the other TCC members at the large restaurant packed with tourists and trudged 200 meters down steep steps and 200 meters up 231 steps to the building.

At the top, we were rewarded with spectacular panoramic views of the rugged Biscay coast and the crashing waves that make swimming impossible, even in the heat of a Spanish summer. But we were lucky. It was cold. It was windy. It was October.

We didn’t have to wait in line to climb.

“Before Game of Thrones we could come up without tickets,” Ricardo said. “After Game of Thrones, we locals need tickets. So you know what we think of Game of Thrones.”

Yes, the world is discovering Bilbao. As the architect Richard Serra put it, it was only a “matter of time.”

If you’re thinking of going …

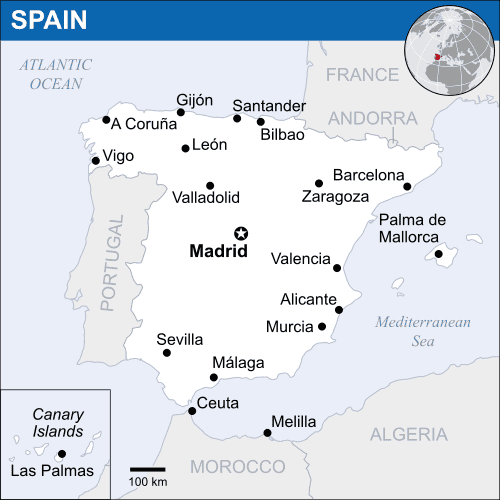

How to get there: Cheap as dirt. Numerous daily flights from Madrid start at €25 one way for the one-hour flight. The 1-hour, 15-minute trip from Barcelona starts at €30. But, of course, watch for the larcenous baggage fees. Train from Barcelona takes 6 hours, 50 minutes and costs €50-€75.

Where to stay: Hotel Bed4U, Avenida de Kirikino 1, 34-944-348-055, https://www.bed4uhotels.com/bed4u-bilbao.html, bilbao@bed4uhotels, 3-star hotel a 15-minute walk from Casco Viejo. I paid $415.57 for three nights.

Where to eat: Restaurante Agape, Hernani Kalea 13, 34-944-160-506, http://www.restauranteagape.com/, info@restauranteagape.com. Modern, gourmet restaurant has whipped up creative Basque dishes for 20 years. Excellent duck in rich brown gravy.

When to go: Avoid Bilbao, as well as the rest of Europe, in July and August. Crowded and humid. Average highs in low 70s in June and September. Winters are mild, rarely dipping in the 30s. During our visit in October it was 50s and 60s with some drizzle.

For more information: Bilbao tourist office, Plaza Circular 1, 34-944.795-760, https://www.bilbaoturismo.net/BilbaoTurismo/es/turistas, 9 a.m.-9 p.m.

Coming Friday: The txoko, the traditional Basque feast.