Budapest: Coming in from the cold one thermal bath at a time

BUDAPEST — We walked into the lobby at about 5 p.m. and it looked like 5 a.m. Men and women sat at modern cocktail tables wearing terrycloth bathrobes as white as new-fallen snow. Sexy glasses filled with burgundy red wine sat in front of them. We boarded an elevator with a couple wearing bathrobes and towels around their necks, their hair still dripping wet.

When we checked into our fourth-floor room, the first things we saw when we opened the closet door were two matching bathrobes, the regal Danubias Spa Hotel Helia crest on the chests. We didn’t bother unpacking. We pulled out our swimsuits, donned the bathrobes and joined the procession in the lobby.

We passed through the lobby bar and a glass door into a long white hallway. Walking by rooms with signs reading “THAI MASSAGE,” “WELLNESS CENTRE” and “DIAGNOSTICS,” we entered a hall that looked like an updated version of the Ancient Roman baths. Three large pools, all of increasingly heated water, sat side-by-side amongst sweeping ferns and lounge chairs. We could see the mighty Danube River outside the big picture windows.

Welcome to life in Budapest. It’s where thermal baths are part of the lifestyle, not just a luxury taken on weekend getaways as Marina and I recently took. Budapest has had a brutal, violent past. However, it is lucky in one regard. It sits atop a geological fault where nearly 8 million gallons of water, in varying degrees of sensually warm temperatures, pour from 123 thermal and 400 mineral springs. Thermal spas dot Budapest like trattorias dot Rome.

This was my third trip to Budapest. I first came while backpacking around the world in 1978 when it was in tight clutch of the communist fist. I returned in 1993 when democracy was as new as a fresh coat of paint. Twenty-three years later I came back to find Budapest as one of Europe’s top destinations. Its bridges are nearly as lit as the partiers in the new trendy “ruin” bars. Its coffee shops are as posh as any I’ve seen in Paris. I felt like I’ve seen Budapest grow up, from a broken, squalid, tortured little girl to the sexy, bright goddess that everyone wants to meet.

Nothing seems more opulent and capitalistic than Budapest’s thermal bath culture. Actually, it has been around as long as the land. The Ancient Romans took thermal baths here when Hungary, then called Pannonia, was part of the Roman Empire more than 2,000 years ago. The Turks made public bathing part of daily life during the Ottoman Empire in the 16th and 17th centuries. By the 1930s, Budapest had become a spa resort, although the languid atmosphere was somewhat stained by the presence of Nazi henchmen and Russian tanks.

With Budapest at peace, we slipped out of our robes and joined a group of Russian and Italian tourists sitting along the rim of the hottest pool, a giant round Jacuzzi with artsy wave decorations on the wall. Every 10 minutes or so the 97-degree water would explode under our bottoms, shooting bubbles everywhere and onto our smiling faces.

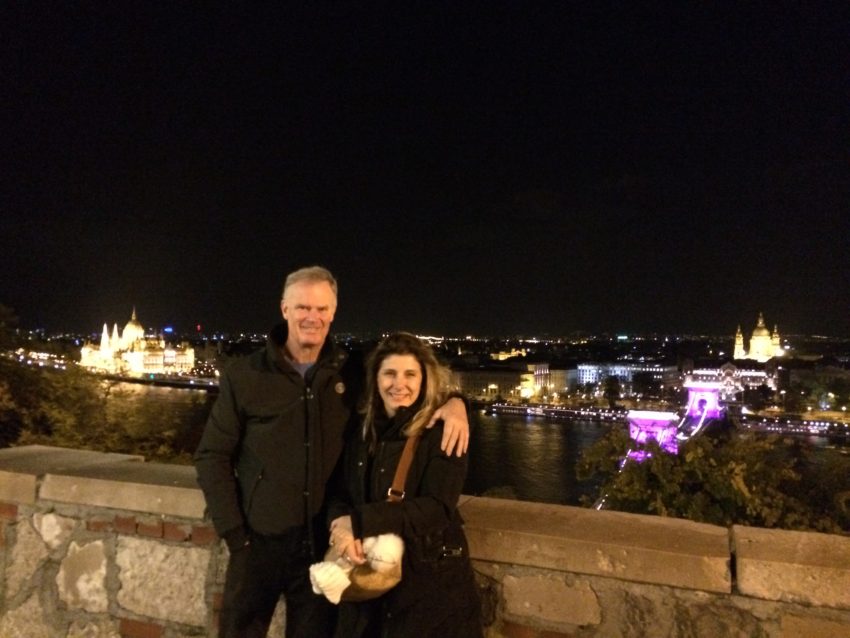

I wanted to show Marina, on her first visit, how much Budapest had changed. I took her to where I spent my first days here in ‘78 as a scruffy 22-year-old getting in touch with my inner Marxist. I took her up the steep fernacular train ride to atop Castle Hill. We stood at an overlook next to the massive Royal Palace, one of the great symbols of Hungary. Like its people, it has been torn down and rebuilt six times in the last 700 years. It hasn’t been used as a residence since the late 17th century. Today it remains a monument of a more glorious time and to the Hungarian National Gallery.

While I’d stood on this same spot nearly 30 years before, I hadn’t seen this view. Under communism, the landscape below was as gray and black as a prison in winter. The Chain Bridge, built in 1849, had a few necessary lights. Some drab office buildings had windows lit. On this night, however, Chain Bridge was lit up in purple, like a stage in Las Vegas. It was in honor or Breast Cancer Awareness Month. Across the river the Parliament Building, 18,000 square meters boasting 142 statues with spires and a dome that make it look more religious than federal, glowed in bright gold. It looked like Prague with a wider river. In fact, the Danube was so wide, the Roman army didn’t bother crossing it. They merely made hilly Buda on the west side of the river part of the empire and left the flat Pest on the east side to the barbarians.

We walked along the quiet, dimly lit narrow streets of the castle and settled into one of Budapest’s newest, trendy restaurants. Magyar Vendeglo has an old wood floor and brick walls with white tablecloths and candles. Classical jazz played on the loudspeaker. It felt warm, like your Hungarian aunt’s house.

Hungarian food is the most underrated in Europe. It’s full of flavor and no grease. Chicken. Pork. Lots potatoes and cheese. And the signature spice is paprika. One of my favorite dishes in the world is chicken paprikash: chicken breasts, spiced with paprika and sour cream served with a heaping helping of potato dumplings. Accompanied by a glass of Egri Bikaver, Hungary’s national wine that translates to “Bull’s Blood,” it was the classic Hungarian meal.

Budapest isn’t the bargain it was under communism. But at least now you have something to buy. Our bill, including service charge and wine, was still a reasonable $57.

The beauty of the old Eastern Europe is it combines the luxuries of the West — good food, posh hotels, gorgeous lighting — with the depraved history of World War II and communism. The combination has attracted me to nearly every country in the old Soviet bloc.

In Hungary, Budapest’s Jewish Quarter sits in the heart of the city. Marina and I knew we’d stumbled upon it when we saw a huge stone wall with a giant bronze tablet urging visitors to read Psalm 23, “The Lord’s Song,” in memory of the 600,000 Hungarian Jews who died in the Holocaust. Behind the wall, 70,000 Jews lived in an area of .12 square miles with up to 14 to a room. Between Dec. 2, 1944-Jan. 18, 1945, a span of six weeks, Nazis and the Hungarian Arrow Cross, the savage Nazi sympathizers, murdered 10,000 Jews. The Danube was a good torture chamber and graveyard. The Arrow Cross would tie three Jews together, throw them in the water and shoot one, forcing the others to sink to the river’s floor.

Today, the same area is the head-pounding pulse of Budapest’s wild nightlife. Amidst all the heavy rock clubs where heavily tattooed youths gyrate to European rock groups and stodgy cafes where young intellectuals gather for long smokes and conversation are what they call “ruin” bars. This new phenomenon from the early 2000s began when businessmen took abandoned buildings and turned them into bars with lots of space. Some have no roofs and are packed in the summer tourist season. On a crisp fall Saturday night, Marina and I ventured into Szimpla Kert, the first ruin bar in town. We walked into a multi-room, multi-floor cave where people from all walks of life sat in neon-lit niches. I walked into one and ordered a szilva palinka, plum brandy that is popular with sailors as in a pinch it can be used as boat fuel.

Marina, her head starting to cave from the kaleidoscope of neon, and me, wondering what those drunk men were doing riding this cast-iron dinosaur, walked out before we started feeling at home.

Most of the drunk youth in the bar probably can’t spell “Marx” let alone know who he is. My Hungarian friends, Ferenc and Rita, sure do. I met Ferenc at a bus stop in 1978. He was a soldier who became my eternal symbol of communism’s major fault: It’s a system that strives for mediocrity and it’s human nature not to want to be mediocre. Under communism, the Hungarians all worked, had roofs over their heads and ate every day. That’s it. Meanwhile, the government opened letters and tapped phones. And people like Ferenc, 23 at the time, lived in a one-room apartment with his mother — and her ex-husband. (You got one free apartment per household, not two.)

Ferenc didn’t like his life. He wanted to open his own flower shop. In 1978, that wasn’t a modest goal. It was a fantasy. When I left him to continue my journey, he handed me his address. He wanted me to place an ad in my old college newspaper to find him an American wife so he can get the hell out of Hungary. The look of desperation in his eyes when I walked away has remained with me forever.

We met Ferenc and Rita, his lifelong friend whom I’d met in 1993, near Rita’s home in South Buda. Ferenc never owned a flower shop. He now works for an agency driving tourists around Budapest and Central Europe. He has a wife and two kids and still has the same healthy physique, round face and dark brown hair I remembered. He just smiles more now.

They took us for lunch to a classic Hungarian restaurant. Negy Mustekas Etterem has no tourists, no English menus and no pretense. It’s just good basic, hearty traditional Hungarian fare and cheap Hungarian wine. Over a big bowl of Hungarian goulash, I asked them about life in Hungary today. Democracy has been a difficult road. Not one political party won re-election in 1994, ‘98 or 2002. However, the right wing Fidesz party won in 2010 and 2014. Today, prime minister Viktor Orban is considered one of the most right wing leaders in Europe. However, unemployment has dropped from 11 percent in 2008 to 4.9 today. His no-entry immigration policies are popular with many right-wing Hungarians. They even built a wire fence on its southern border with Serbia and Croatia. In June they passed a law allowing police to send any illegal immigrants back to Serbia if found within five miles of the border.

Today, Budapest remains incredibly white.

“I like what the Hungarian government is doing here in Hungary,” said Ferenc, a self-described conservative. “Not everybody is satisfied with the activities of the government. There is a development. Recently the economy is going. More than 4 million people have jobs. There are different foreign companies. The car industry is very good in Hungary. Mercedes, Audi, Suzuki, they are here. In Hungary.”

Today’s Hungarians do have more bounce in their step. It’s not just on the dance floor of ruin bars. On our last day, Marina and I joined joggers and families and lovers cruising through Margaret Island, a 2.5 kilometer-by-500-meter-long island in the middle of the Danube. We strolled through the forest of 10,000 trees, a collage of red, gold and green fall colors. Birds sang. People laughed. We passed 13th century ruins and fountains that danced to music, such as at the Bellagio in Las Vegas. During the Ottoman Empire, the Turks used this island as their harem from which all “infidels” were barred.

No one is barred in Budapest anymore. In 30 years it has gone from prison to pristine. The reminders are never far away. Not far from the Jewish Quarter is a museum documenting Hungary’s Nazi and Soviet regimes. It goes by the not-so-subtle name of … House of Terror. It’s in the former headquarters of the AVH secret police who took activists here for interrogation and torture. The walls remain double thick to bury the screams.

An hour later, I was back in the hotel spa with Marina. Our heads tilted back. Our eyes closed. We thought of chicken paprikash and views of mighty palaces and sparkling bridges.

Like Budapest, we came in from the cold.