Drinking in Bulgaria: Rakia, Zagorka and a Sofia pub crawl

(This is the fourth of a five-part series on Bulgaria.)

SOFIA, Bulgaria — A bartender who looks like the Grim Reaper’s mistress hands me my first shot of Jagermeister since college in the ‘70s. She’s wearing a black turban, a nose ring and a full-length black cloak. Her oddly uncharacteristic warm smile makes her black lipstick resemble two snakes searching for prey.

I’m on the ground floor of Terminal 1, one of Sofia’s alternative music clubs that’s slowly filling at 12:15 a.m. It’s a cross section of Sofia’s young adults who are too young to remember when these clubs didn’t exist in Bulgaria and too self absorbed to care what people think they look like.

Standing by the bar, I see a pixie woman with black lipstick and eye makeup that makes her look like she modeled for a Picasso painting dancing alone, her eyes dreamily closed. Another tiny woman in tight jeans and sneakers gyrates wildly at the bar across the way.

Besides being old enough to be the grandfather of every person here, I feel conspicuously overdressed in just white pants and a black T-shirt. Then again, at least I’m dressed.

Sprinkled in the crowd is a group of about a dozen men in their early 20s dancing, drinking and laughing — in bathrobes. I asked one, um, “Why?”

“Special party!” he screams as his head continues to bob to a house rock tune I’ve never heard and hope to never hear again.

Bulgaria’s drinking habits

I’m at the tail end of the Sofia Pub Crawl, a one-night dip into the Bulgarian capital’s party scene. I was curious about the nocturnal habits of Bulgarians. East Europeans were always up for a night out. Even when I visited Budapest in 1978, it was party central for all East Europeans trapped behind the Iron Curtain. I met Romanians, Poles and, yes, Bulgarians all toasting with Egri Bikaver, Hungary’s trademark wine meaning Bull’s Blood, and palinka, the country’s brandy popular with European navies as it also doubles as boat fuel.

It’s 31 years since communism fell in Bulgaria and they have the essentials for a great party scene. A once-floundering wine industry has rebounded, clubs and open-air drinking venues are popping up all over the country. One product that has transcended generations is rakia, Bulgaria’s 40-proof plum brandy. Oh, and bottled beer doesn’t come in anything less than half-liter bottles.

Nazdrave!

That’s “Cheers!” in Bulgarian. It’s the most essential word you should learn in a country where Bulgarians are famous for putting strangers under their wing for a fun night out before you can alert authorities.

“Bulgarians are tough drinkers,” said Valentin Nikolov, 27, a sales and support agent who took me out on the town in the Black Sea port city of Varna with his girlfriend. “They can drink quite a lot. Drinking is kind of a culture. You don’t sit with a salad without rakia.”

Sofia Pub Crawl

The Sofia Pub Crawl, one of the city’s many tremendous guided tours, is a good place to start. Meeting at Crystal Garden are two Frenchmen, a Romanian and two other Americans, one in Bulgaria to teach English to gypsy children and the other an Air Force man stationed in Germany with a weekend off. Crystal Garden is one of Sofia’s top gathering nighttime gathering places. It’s a huge block in Sofia’s lively center filled with trees, open space and park benches. All around us are small groups of Bulgarians with big bottles of beer. One strums a small, odd-looking guitar.

It’s Friday night. It’s 8 p.m. The June temperature is about 75. It’s a perfect night for drinking in any country.

Guiding us is Giovanni, a transplanted Italian who moved to Sofia about three years ago for a change. We are a few meters from the first stop of the night. Giovanni says this bar has anchored Crystal Garden for more than 50 years and I can tell it’s a product of the dull, utilitarian communist times just by its name.

Bar Bar

Bar Bar.

The bar is as basic as the name. Bar Bar is small and dark and as eerily lit as an adult haunted house. A couple of small overhead lamps illuminate two long shelves of booze bottles and a crude wooden counter. Giovanni explains that there was a move to close it but it got enough signatures to not only keep it but also make it a National Heritage Site.

A pretty woman in a halter top and Covid mask hands me a tall, ice-cold bottle of Zagorka, one of Bulgaria’s three most popular beers and has been around since 1902. I take it outside with the group where most of the Bar Bar patrons have gathered. It’s a wide age group from 20s to 40s, all casually dressed in shorts, jeans and comfortable shoes.

Maybe it’s early but it’s a laid-back atmosphere. I see no signs of binge drinking or early drunkenness, unlike in Northern Europe or Great Britain.

“What’s getting more regular in Sofia is two ways of drinking,” says Yoan Dimov, 22, also a Sofia Pub Crawl tour guide. “Obviously you saw the bar drinking culture, people drinking in a public space. During the warmer months this is pretty dominant. People going in a park or in front of their living space if they live in one of those Soviet blocks. You have some benches in front of that and with friends you can grab a few beers. You have central areas where people go out for a few beers. Then they can head for a bar.”

Bar Friday

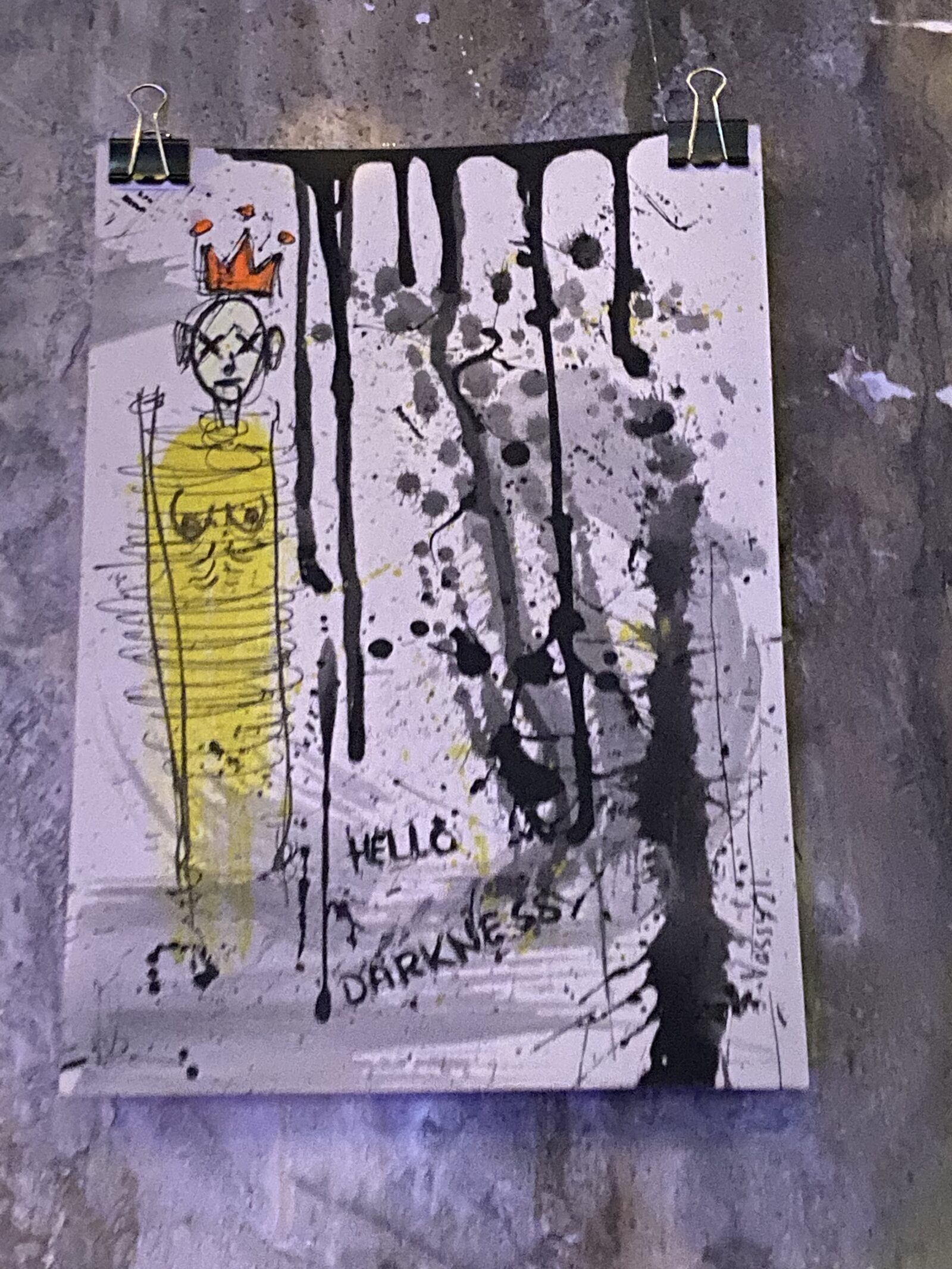

Our second stop was just down the street in Bar Friday. It’s a large, wide-open space held up by scruffy black columns featuring weird paintings from an obviously tortured artist. The five-year-old bar used to be the office of a military newspaper during communist times.

A small, skinny, middle-aged bartender with a tired look and two-day-old stubble hands me another Zagorka. I notice one wall is oddly lined with rubber duckies. A Jameson Black Barrel sign hangs with the paintings which are a mixture of violence and angst.

We all take turns ordering group shots of vodka and lime juice which has a hauntingly similar taste to kamikazes. I get savage flashbacks to 1981 in Las Vegas where I insanely took part in a kamikaze shots contest with a guy who weighed 250. I had 13 shots in an hour — and lost.

This is going to be a long night.

I ask Giovanni what he likes about Sofia more than Italy, where in the South everyone is a teetotaler.

“It’s Saturday night every night!” he says with a laugh.

Club Stroeja

Our third stop is Club Stroeja. it’s tucked innocently in a building with dentist offices. But inside and down a flight of stairs is a long room with brick walls and concrete floors. Lanterns that look like rooster cages hang over the long wooden bar. Faded photos of live concerts hang on the walls.

We all congregate on a small elevated area with a Foosball table. I set up camp at the bar when I see they sell Russian Standard, one of the best vodkas in Russia. I order the group shots and am crestfallen when I learn the bar has no ice. Unchilled vodka shots are way too Marxist. I drank them once in Moscow and woke up wanting to invade Ukraine.

With Hall & Oates’ “You’re Out of Touch” playing on the loudspeaker, Giovanni tells me Stroeja was one of Sofia’s top clubs in the ‘90s and 2000s. As he says this, an old drunk possibly left over from those decades stumbles toward us. His crooked smile gives off the air of someone who wants money for a drink but not even nearby Bulgarians know what he’s saying. Don, the American Air Force guy, befriends him and takes him to the bar to keep him company.

Don becomes the group hero.

We have about a 15-minute walk to our final stop of the night. We pass numerous restaurants with dozens of outdoor tables filled with people. Bars with drinkers spilling out into open spaces. No one seems drunk. No one is loud. It’s as comfortable a drinking environment as I’ve experienced.

Terminal 1

Terminal 1 is down a flight of stairs where we descend onto a balcony looking out over a vast dance floor. The music is the same mind-numbing, head-pounding claptrap that’s the same in every club from Barstow to Bangkok. I drain my Jagermeister hoping enough different shots will make me pass out and I can’t face the music.

I loathe dancing and instead stand by the bar and observe the drinking capacity of the young Bulgarians. They seem sober. But it’s early. It’s only 1:30 a.m. I feel like a wildlife observer at the Serengeti.

I ask Yoan about youth drinking in Bulgaria.

“We have a very early age in terms of your first example with alcohol,” he says. “For example mine was around 14 years old. And I don’t mean just having a sip from my dad’s beer. I mean getting out with older guys and girls and they have some beer and vodka and so on. For good and bad — mostly bad — it has some good aspects. We get used to alcohol pretty early.

“The bad aspects are obvious. It leads to addiction and generally accepting this way is the only way of having fun. But the good aspect is we know our limits when we are 18 or 19 so we don’t get absolutely crazy and make trouble.”

The sexual dance

The interaction between men and women in Bulgaria intrigues me. Even with half the men in bathrobes, Terminal 1 doesn’t have the feel of a meat market. Neither does any other place I visit. I didn’t hit any high-end disco. I never heard of any divorcee bars as you see in suburban U.S. But the sexual dance is more of a slow square dance than a sexy tango.

“A lot of people do meet in bars,” Yoan says. “There is a flirting culture. In my experience it’s different in Western Europe: Spain, Netherlands, even Italy, the partying is a little bit faster. It’s almost non-existent the one-night stand culture here. Here most girls, even if you do meet them in a bar, you just take their number and go on a few dates, maybe dinner, maybe go to a bar. It’s not that fast here. We don’t have the hook-up culture.”

Later in the week, I find myself in Varna on a necessary one-night layover before my flight back to Sofia. I’m not expecting much. I’d spent three glorious days on a near empty, sandy beach at famed Sunny Beach, and want a couple drinks, dinner, bed and flight.

On the corner of my hotel at the end of a narrow street are a craft beer shop and wine store adjacent to each other. Averi Beers has more than 200 different bottles of beer and eight on top. They serve me a Sessions IPA in a long plastic bottle that looks like a giant urine sample and I take it to a big barrel they use as tables.

Bulgarian wine

Bulgaria’s beer scene takes a back seat to its wine and rakia but it’s slowly growing. The country has about 20 craft breweries, oddly few considering the average Bulgarian drinks 73 liters of beer a year, 15th in the world.

But you don’t go to Bulgaria for beer. You go for wine and rakia. Next door at Wine Not Wine Shop (Get it?), wine bottles from around Bulgaria fill two 7-foot-tall wine racks in the tiny store. The young, fit wine patron with a neat beard hands me a nice Moscato from the Struma River Valley in southwest Bulgaria.

The wine scene in Bulgaria is making a slow comeback. Bulgaria’s wine industry dates back 8,000 years when the Thracian warrior tribe settled the area and produced some wine. In the 1980s, Bulgaria was the fourth leading wine producer in the world. But when communism ended, so did state funding. The wine industry flopped in the ‘90s. But in 2017, Bulgaria sold 1.2 million hectoliters (31.7 million gallons) of wine.

Traveling around Bulgaria by bus, I see vineyards everywhere. The Black Sea coast has 30 percent of the vines and produces a nice Riesling and a native wine called Dimyat, one of the most widely produced white grapes in Bulgaria. South of the Balkan Mountains produces Muscatel and Rkatsiteli, popular in the old USSR. Movrud, probably Bulgaria’s most famous wine, is produced in southern Bulgaria and the Struma River Valley also makes a wine called Shiroka Melnishka loza, or Melnik, the favorite Bulgarian poison of Winston Churchill.

At Wine Not, I meet Valentin and his German girlfriend, Sonja Michels. They are educated professionals in their late 20s who met while working at the same hotel in the Italian Dolomites. We had a lot in common — namely Italy and drinking — and they take me to a restaurant I’d planned to hit all along.

Stariya Chinar is a sprawling indoor-outdoor restaurant right on Varna’s huge port. We sit outside on a beautiful 75-degree evening and order Bulgarian salads, spreads and BBQ ribs.

Rakia

But first comes the rakia.

“Rakia is the choice of every generation in Bulgaria,” Valentin says. “It’s like a sacred thing. It’s so deep in the culture, you can’t live without it anymore.”

Anyone who travels around the Balkans and points nearby is familiar with it. Also known as rakija in Serbia, raki in Albania and rachiu in Romania, rakia in Bulgaria goes back to at least the 14th century when a piece of pottery was found with rakiya inscribed on it. Archaeologists later discover fragments of distilling equipment used to make rakia. They dated the fragment to the 11th century, leading historians to determine rakia was invented in Bulgaria.

Traditionally, it is served with salads for which Bulgaria is famous. Every menu has at least six different salads. I had shots at my first dinner in Sofia and with Valentin and Sonja. High-end rakia really is quite smooth and you can taste the plums. Just stop at one. Bulgaria isn’t a college campus.

“The proper way of drinking it is not to get drunk with it,” Valentin says. “Bulgarians don’t get drunk with it. It’s not happening.”

We end our evening at Cubo, a huge outdoor bar on the port where we take drinks to a table and stare out at the Black Sea. I had started the evening with beer, went to wine, switched to rakia and end it nursing more wine in a plastic cup. The sea is as calm as I am.

In Bulgaria, every hour is happy hour.

If you want to go …

Guided tour: Sofia Pub Crawl, www.thenewsofiapubcrawl.com, 359-89-223-7780, meets Thursday through Sunday at 9 p.m. at Crystal Garden on the corner of Ulitza Rakovski and Boulevard Tsar Osvoboditel. 15 euros per person. Tour went every night of the year before pandemic.

Where to drink in Sofia:

Bar Bar, ul. 6-ti Septemvri 7, Crystal Garden, 359-88-345-2312, 11 a.m.-3 a.m.

Bar Friday, ul. General Yosif V. Gourko 21, https://barfriday.bg, 359-89-362-4062, 6 p.m.-6 a.m. Monday-Friday, 7 p.m.-6 a.m. Saturday, Sunday.

Club Stroeja, ul. Lege 10, Stroeja – Home (facebook.com), 359-88-597-4666, 8 p.m.-6 a.m. Monday-Saturday, 8 p.m.-midnight Sunday.

Club Terminal 1, ul. Angel Kanchev 1, (2) Club Terminal 1 | Facebook, 359-88-921-9001. 9 p.m.-6 a.m.

Where to drink in Varna:

Cubo, 9000 Primorski, (2) Cubo | Facebook, 359-89-842-5232, 8 a.m.-4 a.m. Monday-Saturday, 8 a.m.-midnight Sunday.

Averi Beers, ul. Arhimandrit Filaret 9, https://averibeers.com, 359-88-785-6207, 10 a.m.-10 p.m. A bottle shop with outdoor seating.

Wine Not Wine Shop, ul. Arhimandrit Filaret 9, (2) Wine Not? | Facebook, 359-89-932-2525, 11 a.m.-9 p.m. Tuesday-Saturday, 2-9 p.m. Sunday.

July 10, 2021 @ 8:31 am

Not now John!

At the start of the Covid19 pandemic you were a tad authoritarian, now you appear to be war weary and have thrown caution to the wind. The vaccine does not totally stop the possibility of contagion or infection it appears only to moderate the symptoms. Stay smart, play safe.

January 28, 2022 @ 4:09 pm

“For complete happiness, man needs,

Sovereign and Glorious homeland ”

Simonides Keoskey / V century BC /

“And the Canadians to become happy,

they must know and follow,

theirs historic destination”

Enchev, I. / XX century AC /

January 28, 2022 @ 4:13 pm

“For complete happiness man needs,

Sovereign and Glorious homeland ”

Simonides Keoskey / V century BC /

“And the Mankind to become happy,

they must know and follow,

their historic destination”

Enchev, I. / XX century AC /

August 23, 2023 @ 6:07 pm

excellent article. I shall be visiting Sofia next month and shall look for some of these watering holes.

how does Bulgarian beer stack up with other beers in eastern Europe?