Iasi Pogrom: A little-known dark period in WWII revealed in riveting museum in charming Romanian town

(This is part of a series of blogs on Moldova, Romania and Transnistria.)

IASI, Romania – Traveling around Eastern Europe is like a World War II ghoul tour.

Let’s see, in Riga I visited the Latvian War Museum where I saw a photo of a weeping mother crying at the infant in her arms moments before a Russian soldier shot her in the head. In Vilnius, Lithuania, inside the old KGB building is the Lukiskes Prison where I entered the torture room heavily padded to muffle the prisoners’ screams. Then in Berlin I toured the old Stasi prison where 3,000-4,000 prisoners died.

I could go on. Reminders of mankind’s unthinkable cruelty are everywhere. Last month I even stumbled onto one in Iasi, a pleasant, park-laden Romanian town just inside the Moldovan border. The Iasi Pogrom Museum is a slice of World War II history I didn’t know. No wonder. The museum is only three years old and I never even knew how to pronounce the town it’s in until after I arrived.

It’s pronounced EE-ahsh and behind its pretty parks and statuesque Palace of Culture is an unassuming building with memories of one of the darkest episodes in World War II.

On June 29, 1941, Romanian troops ordered by prime minister Ion Antonesco, a major Nazi ally, began a massacre that slaughtered a third of Iasi’s Jewish population and ordered hundreds onto death trains for concentration camps.

The museum’s modest two-story building has riveting photos of bodies in piles, descriptions of train conditions that killed prisoners before they even reached the camps and a documentary where survivors talked of the horrific atrocities they experienced.

Entering off the street, I passed through a clearing where firing squads gunned down thousands of people. Entering the front door a friendly, knowledgeable young historian named Ana Maria guided me through the museum.

Iasi Pogrom history

First, some background: The building was built in the late 19th century in Iasi’s Jewish neighborhood one block off Bulevardul Carol 1, the main drag that cuts through the center of Iasi. In 1914 the building was given to the Romania Literary Society and the education board used it until 1934. That’s when the Ministry of Foreign Affairs turned it into a police station.

The dark period had begun.

Five years later, World War II began and Antonescu, a former career military officer and lifelong anti semitic, became prime minister. He aligned Romania with Nazi Germany and named himself foreign minister and defense minister.

Jews had inhabited Iasi since the 1500s yet not being Romanian Orthodox, they were not considered citizens of Romania. At the time of Antonescu’s appointment, out of Iasi’s population of 111,669, 33,135 were Jewish. They were not allowed to marry Romanians. They were not allowed to hold office.

With Iasi only 75 miles (125 kilometers) from the Soviet border, Jews were also feared to be Soviet allies and a security threat. Antonescu billed the war with USSR as a war against “Judeo-Bolshevism.”

In 1941, Russia heavily bombed Eastern Europe and word got back to Antonescu that the Jews were hiding weapons and tipping off Russians on where to drop the bombs. On June 24 and 26 Russia bombed Iasi – everywhere but the Jewish neighborhood.

The massacre

Antonescu wanted revenge. In the last week of June, he ordered a mass grave dug on the outskirts of Iasi. On June 29, he called all Jews, most of whom had been in hiding, to the police station under the cover that they could receive a pass allowing them to roam the city freely. It was a ruse. He just wanted to identify all the Jews.

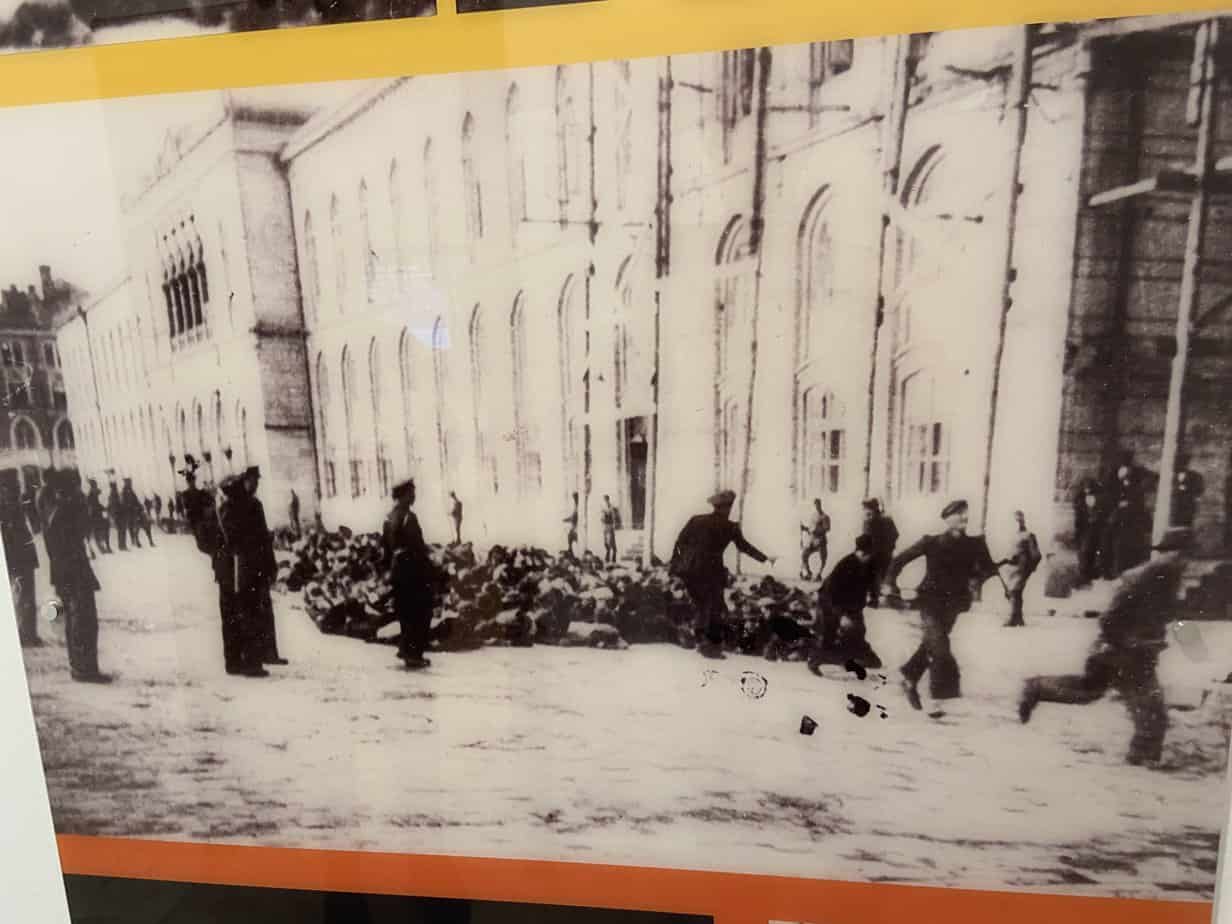

They were immediately arrested and brought into the same building where I roamed. Thousands were hauled in the side courtyard and gunned down. From June 29-July 6, according to Romanian authorities, an estimated 13,266 died.

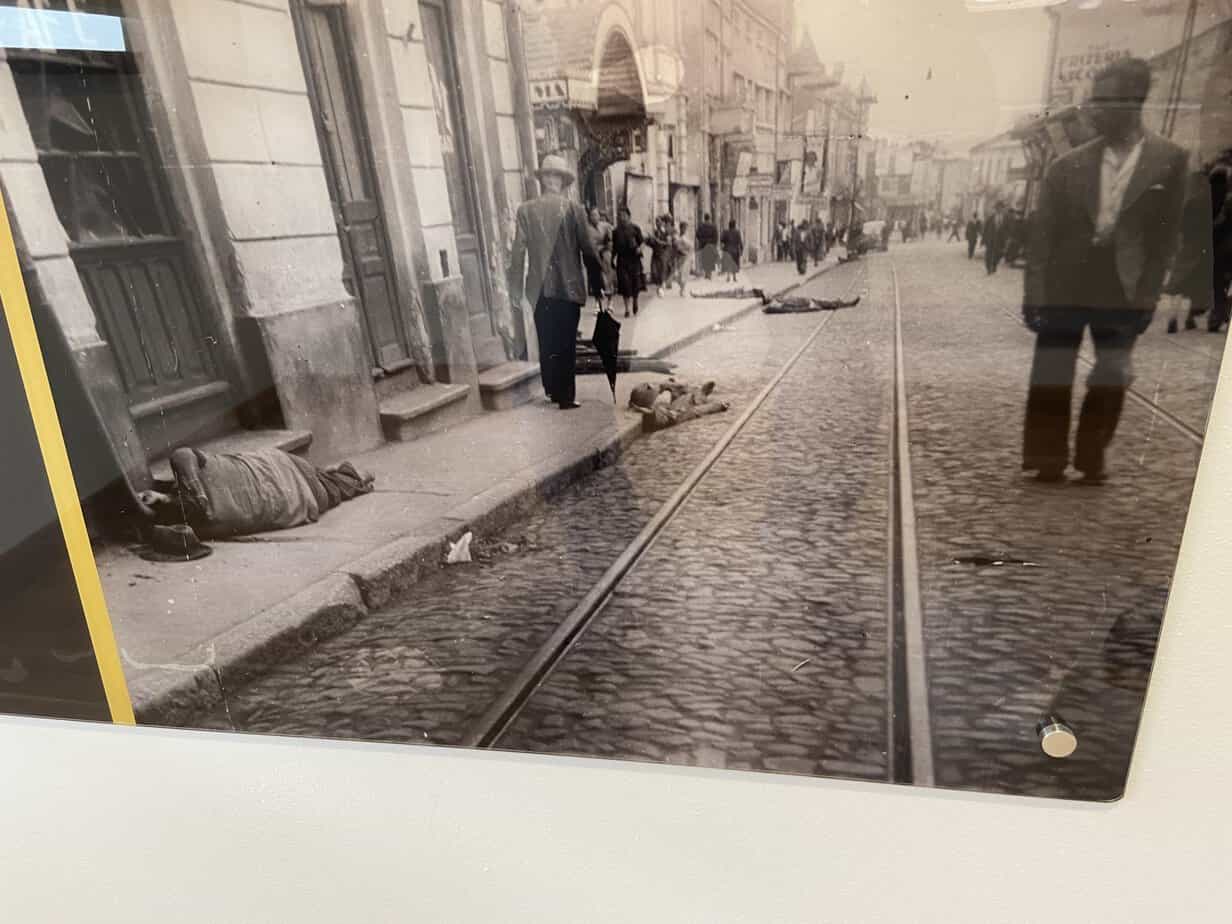

On June 30, survivors were taken to two trains. They were ordered to lay on the ground before they boarded. According to one survivor, when locals walked through the prisoners in front of the station, a guard yelled, “You can step on them. They are only Jews.”

One train went to Calarasi, 230 miles (387 kilometers) to the south; the second went to Podu Iloaiei, 12 miles (20 kilometers) to the north. The first train took 6 ½ days to reach Calarasi; the second train took 10 hours. The trains didn’t suffer mechanical problems. It was Romania’s own way of torturing prisoners.

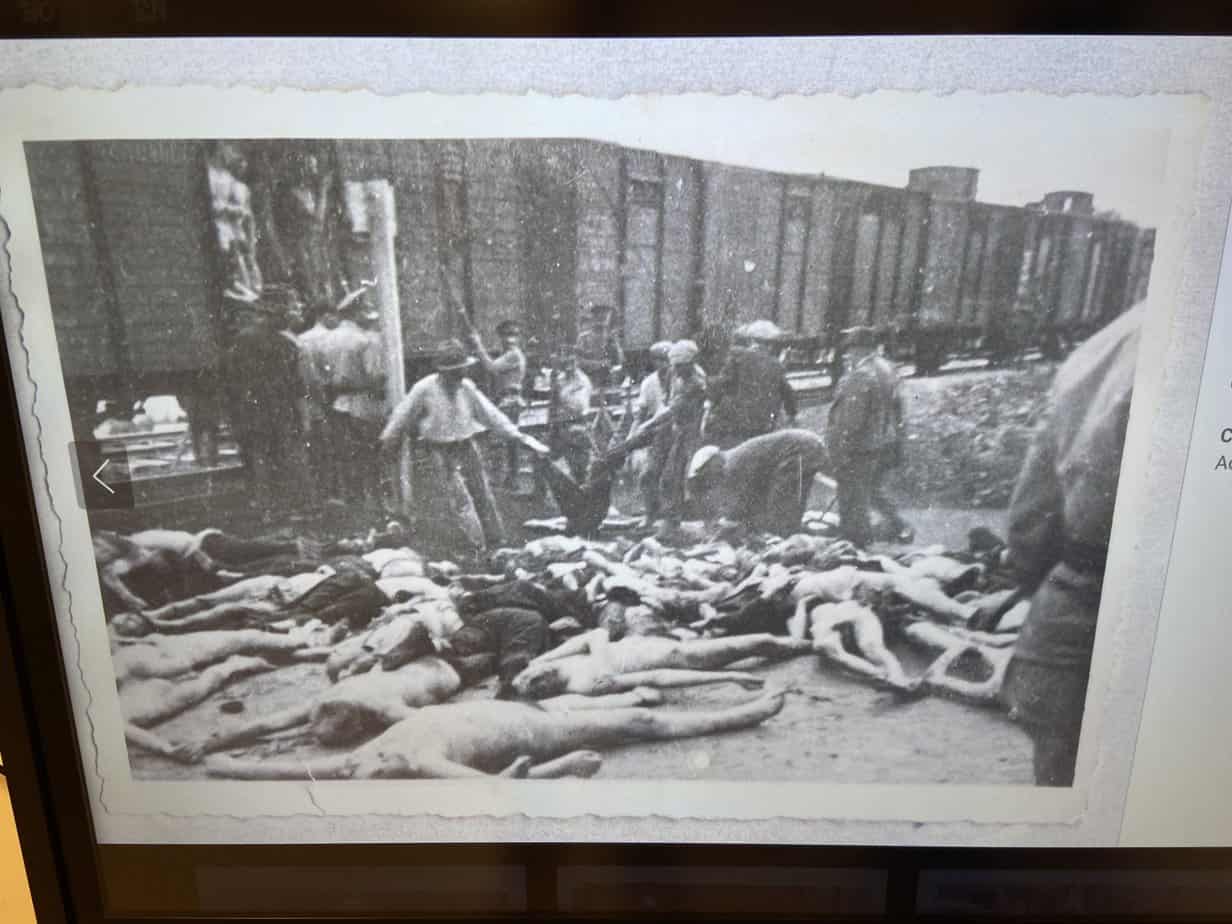

They crammed 120 men into boxcars meant to hold only four horses. Trains were so packed, prisoners couldn’t sit. In the middle of summer, the trains were steaming beyond imagination. Romanian officials covered even the slits between the train cars’ wooden boards. Prisoners died of dehydration.

Of the 2,500 prisoners who left Iasi, only 1,100 survived. The rest were thrown out of the train as they died or were used as benches.

In the labor camps, survivors in the documentary talked of an entire diet consisting of bread made from flour, water and soil.

The museum

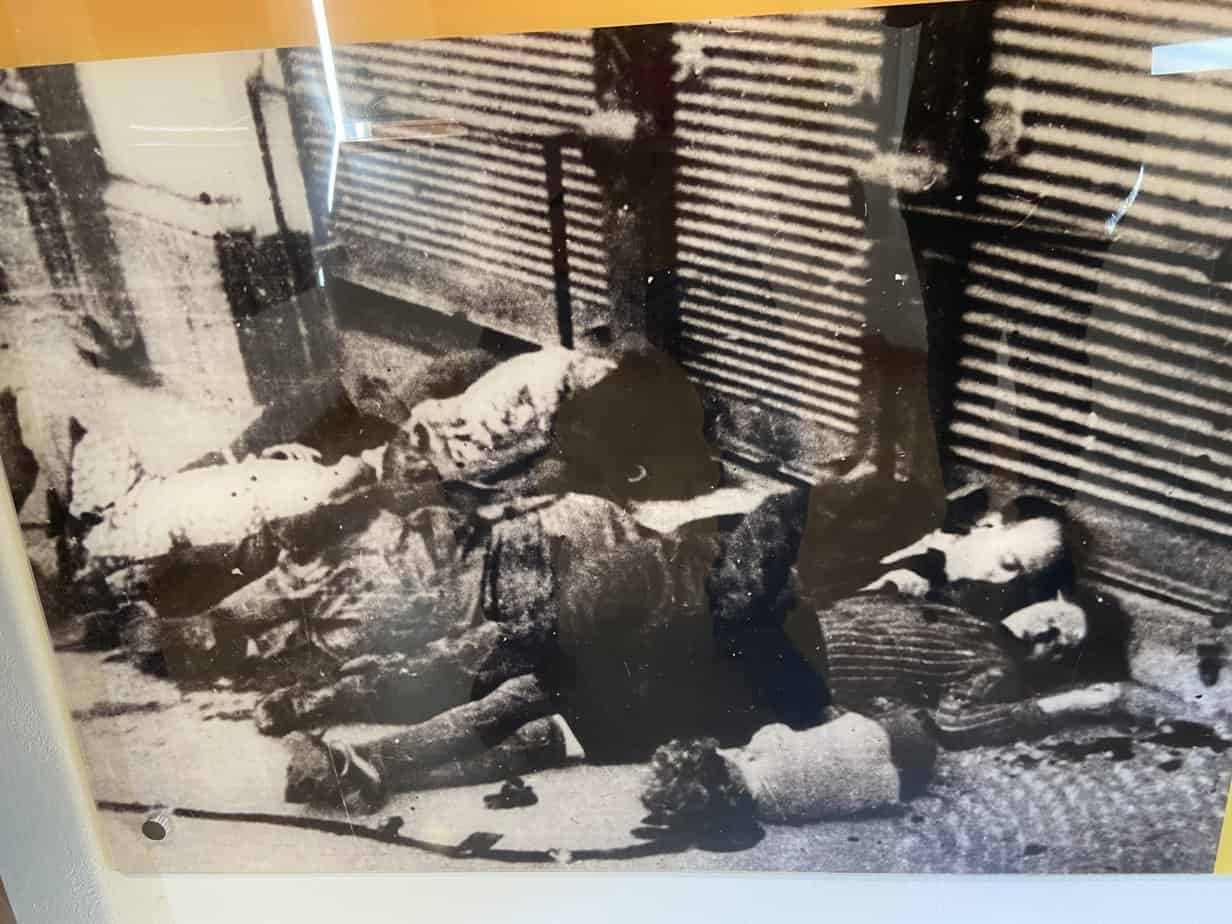

The museum’s plain white walls are covered with horrifying photos and descriptions. One shows a pile of executed bodies. One couple is even in an awkward embrace as if they were shot at the same time. Another shows a man walking by a body laying in a street gutter. One more shows the ground outside one of the sweltering train cars covered with bodies.

The grotesque images were endless: Naked men herded into camp. Other naked bodies lay face down, dead.

In the museum’s small theater, I watched a documentary where three survivors were interviewed in 2010. One talked about walking across scattered brains in the streets and how they stuffed 10,000 Jews inside the courtyard where I entered.

Although in their 80s and 90s and having full mental capacity, they talked through tears.

After the Nazis lost, Antonescu, reportedly responsible for the deaths of 400,000 people, was arrested and put on trial in May 1946. He was found guilty on charges of war crimes and treason and on June 1 was executed by firing squad near a prison fort in Jilava.

He left a letter to his wife telling her to join a convent and that some day his deeds will be reconsidered in a positive way. He called the Romanians “ungrateful.”

After the tour, I walked to Bulevardul Carol I and at Gist, a hip coffee bar, I ordered a banana-chocolate smoothie. I sat at an outdoor table in sunny 72 degrees with tattooed students chatting over steaming mugs of joe, with sharply dressed women pouring over their laptops and cellphones.

In the 21st century, all ghoul tours in Eastern Europe have happy endings.

If you’re thinking of visiting

Getting there: Numerous direct flights leave from Bucharest. Flights on Tarom, Romania’s national airline, start at €96 one way. The flight is 1 hour, 10 minutes. Trains leave three times a day. The six-hour ride is €34.

Where to go: Iasi Pogrom Museum, Strada Vasile Alecsandri 6, 40-747-499-400, https://www.muzeulliteraturiiiasi.ro/muzeul-pogromului-de-la-iasi/, muzeul.literaturii@gmail.com, 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Tuesday-Sunday, €2.

Where to stay: Grand Hotel Traian, Plata Unirii 1, 40-232-266-666, https://grandhoteltraian.ro/ro/, receptie@grandhoteltraian.ro. Elegant four-star hotel on a major plaza in the middle of the city. I paid €160 for two nights including breakfast.

Where to eat: Carciuma Veche, Strada Ion C. Bratianu 30, 40-727-255-288, https://carciumaveche.ro/, restaurant@carciumaveche.ro, 8 a.m.-10 p.m. Romanian comfort food. My Romanian meatballs with mashed potatoes, sauerkraut and a beer was €17.

When to go: Fall is best, My days in October were in the 60s. Summers are hot and humid. January it’s in the 20s and 30s. The spring has the most rain.

For more information: Tourist Information Center, Plata Unirii 12, 40-232-261-990, www.turism-iasi.ro, turism.iasi@gmail.com.

Next Tuesday: Transylvania.