Moldova wine: National Wine Day and world’s largest wine cellar plenty to drown my Italian-trained palate

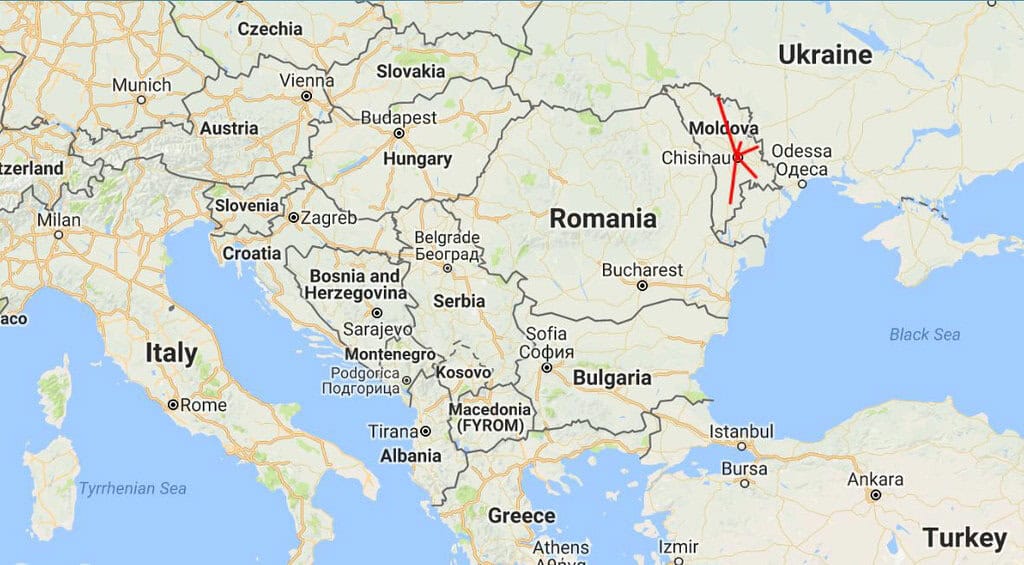

(This is the first of a series of blogs on Moldova, Romania and Transnistria.)

CHISINAU, Moldova – Great National Assembly Square is a giant slab of concrete that has anchored this capital of the poor, small nation of Moldova since the early 19th century. Its highlight, the Arc de Triomphe, a smaller version of the one in Paris, drips with former ties to Mother Russia. It was built in 1841 to commemorate the Russian Empire’s victory over the Ottomans. A marble tablet from 1944 honors Russia freeing Moldova from the Nazis.

The square has been the site of working demonstrations in the early 20th century and strikes between the two World Wars. It harks back to a time when Moldova was in the crosshairs of the Ottomans, Nazis and Soviets.

But on a gray, drizzly morning earlier this month, anger and threats were replaced by smiles and toasts. For two days, Moldova was the center of the international wine scene. The 23rd annual National Wine Day of Moldova attracted me and more than 100,000 others to discover and celebrate one of the fastest growing and underrated wine nations in the world.

Booths from Moldova’s three wine regions encircled the square. Pretty Moldovan women in traditional embroidered vests and flower-laden blouses made generous pours from more than 100 wineries. Bands ranging from Moldovan folk to pop to hard rock played on a big stage while wine producers boasted of their wine and their industry.

I had booked an apartment not far from the square. The entrance to the building was in the rear which looked like it hadn’t been touched since the collapsed USSR let go of Moldova in 1991. A gray brick apartment block with exposed wires hovered over a bright red door.

But the living room was huge, the bedroom cozy and the bathroom spotless. Besides, I was in Moldova to drink wine, not to analyze Soviet architecture.

I had tried Moldovan wine occasionally in Italy where my tastes have advanced me to the point of being spoiled. I liked Moldovan wines enough to make me curious. Turns out, I was one of millions who are now discovering them.

Moldova wine fun facts

Some facts I didn’t know about Moldovan wine:

- Moldova, just a bit larger than Maryland, has the highest percentage of landmass devoted to vineyards in the world at 4 percent over 316,000 acres (128,000 hectares).

- In the last five years, Moldova wines have won 6,500 international medals.

- It exports to 75 countries – not including Russia which once made up 95 percent of its exports but its war with Ukraine has made exporting expensive and problematic.

- It boasts the largest wine cellar in the world with the winery Milestii Mici holding 2 million bottles in 200 kilometers of tunnels, five kilometers of which I traveled and three wines of which I drank. (More on that below.)

After two days diving into as many wineries as I could and traversing the country for a week, I learned something more important besides the word Noroc!, Moldova’s Romanian word for “Cheers!”: Moldovan wines are excellent, and they’re cheap. Best of all?

No headaches. Eat that American winemakers.

The fair

Not to say I was thirsty, but I believe I was the first of 100,000 visitors to enter the festival. I walked to an info point where a pretty Moldovan woman sold me a pass for 250 leu. For the equivalent of about €13, I got 12 glasses of wine. Not tastings.

Glasses.

She gave me a small plastic glass with a nerdy string to hang it around my neck. It made me look like a drunk uncle but became necessary while holding a notebook and tape recorder.

I arrived with as much knowledge of Moldovan wine as I did Amazon vegetation. I had never heard of any of these grapes, let alone the wineries. My first stop was at Castel Mimi winery, started in 1893, where I had something called a Sanzienele. It was wonderful, a little sweet with tastes of apricot, grapefruit and gooseberry. (I shamelessly plagiarized that from the literature. I can’t separate tastes with a chainsaw.)

I do, however, know prices. The Sanzienele retails for €10. I thought, I think I’m going to like this country.

Then at Domeniile Davidescu, I had one of Moldova’s signature grapes: the Neagra. The winery’s Cabernet Sauvignon-Neagra was terrific with touches of black cherry, currant and cinnamon. It sells for €16.

At the Kamber booth, I met Mihail Druta, the tall, distinguished head of the Moldova Sommelier Association. I threw him a softball: What makes Moldovan wine special? He smiled.

“That’s a very nice question,” he said in perfect English. “First of all, you need to understand the history of winemaking in the world.”

Moldova wine history

He proceeded to spew some fighting words. He said winemaking didn’t begin in the Republic of Georgia, which I’ve chronicled. He says it began in Moldova. According to History of Moldovan Wine, evidence of grapes being grown in the area date back 25 million years ago. They were cultivated as early as 2800 B.C. and winemaking began about 2000 B.C.

They traded with the Greeks in the 3rd century B.C. and the Romans in the 2nd century A.D. The Moldova state began in the 14th century, and grape growing flourished in the 15th century when Stephen the Great, one of Moldova’s greatest leaders, became one of its most famous guzzlers.

In 1812 when Moldova became part of the Russian Empire, it grew more and in 1837 the Russian government began supporting the industry financially. At one point, the area produced 12 million liters of wine a year.

Two world wars damaged millions of vines but under Soviet rule in the 1950s, 370,000 acres (150,000 hectares) of vineyards were planted over 10 years. In the ‘80s, Soviet president Mikhail Gorbachev tried curbing the USSR’s growing alcoholism by prohibiting the sale or possession of booze and had 30 percent of Moldova’s vineyards destroyed.

The prohibition didn’t last nearly as long as a Russian winter. What did last was Russia’s 2006 ban on Moldovan and Georgian wine over diplomatic issues. At the time, Moldova exported 80 percent of its stock to Russia.

That lasted two years but then Moldova pissed off Russia again in 2013 by announcing it would join the European Union. In came another ban and more economic stress.

The Moldovan wine industry needed a drink. Then it came up with a plan.

“We found other markets in Northern Europe, Asia, the U.S.,” said Cristina Pavlov of the Domemiile Davidescu winery. “It’s hard to sell to Russia. They like sweet and semi-sweet wines. We’re developing high-quality dry wines.”

Moldova began emphasizing quality over quantity. Turns out, folks in Beijing had a more discernible palate than those in Moscow. Taste went up and so did price. The Moldovan wine industry was saved.

Revenue from Moldovan wine this year is expected to bring to the country, the poorest in Europe, more than $1 billion and represents 5 percent of its total exports. Yet it’s so inexpensive. I never tried a wine that was more than €25 a bottle.

“It’s cheap now,” said Druta, the sommelier. “But when Moldavian wines are more popular, prices will go up.”

Milestii Mici

It’s not like Moldovan wine has been hiding underground all this time. Well, actually it has been. That is exactly its claim to fame. Way back in 2005 it made the Guinness Book of World Records for having the largest wine cellar in the world.

At the time of the recognition, Milestii Mici had 1.5 million bottles of wine. Since then, it has added 500,000 more. That’s 2 million bottles from the same winery. And no, they’re not stored in your basic wooden wine rack.

They’re stored in tunnels that snake 120 miles (200 kilometers) from 50-80 meters underground.

“This is the pride of our company and the pride of our country,” said Emil Racovita, the winery tour guide.

In Chisinau, I hopped in a marshrutka, a large van seating about 40 people that serves as Moldova’s main mode of public transportation around the country. For about €2.50, I got a 45-minute ride into rural Moldova and a kaleidoscope of fall colors.

The driver dropped me off in front of a huge Milestii Mici sign and told me to walk down the narrow side road. After 1,000 meters of forest I came across this makeshift stone fortress. Water poured from a huge fountain into wine glasses circling the base.

I joined two young Japanese women with Emil. We went through a door and into a tunnel that looked like a set for a slasher film. Dark and foreboding, it was lit by lanterns hanging from the stone walls.

The tunnel tour

We got in a little train that you see carrying tourists through amusement parks and began descending into the bowels of the wine cellar. We turned a corner and were surrounded by wine bottles. Stacked in large cases in three tiers from floor to ceiling, they stretched for about 100 yards until the tunnel curved.

It was like being inside a river of wine.

“We’re 45 meters below the ground,” Emil said, “and we’re going deeper.”

How does one winery store 2 million bottles of wine? Easy. You build the winery in a mine.

For nearly 200 years, this space was a limestone mine for Russia and the USSR. You can still see the lines on the walls left from the extraction machinery. They extend 200 kilometers all the way to Chisinau. About 65 kilometers are filled with wine filling 1,300 cases.

Picture that. You could drive for 40 minutes and see nothing but wine bottles. Two million of them. Stacked end to end, the bottles would stretch from Rome to Sicily.

“If you don’t believe me, you can count them,” Emil said.

The tunnels remained a mine until 1969 when the Soviet Union thought 200 kilometers may be enough – may be enough – to quench the massive country’s thirst for wine. Milestii Mici, named for the nearby community, opened that year.

We descended farther into the cellar and turned into an area where all the cabinets were numbered. Each one was stacked to the brim with bottles.

“These are our private cabinets,” Emil said. “Each cabinet has an owner. Even you can be the owner of a cabinet but you have to follow three rules: First rule being that you must pay €500. Second rule that in every cabinet you have to have at least 50 bottles of wine, and the wine needs to be from our company. And the third rule is we are not making any deliveries.

“You have to come here personally and take the bottle or trust the person who’ll do it with you.”

We drove farther down and stopped at a door. The tunnels have their own seismic station which attracts scientists after every earthquake. But the limestone has properties to absorb the vibrations.

“So if there are earthquakes, you can come here,” Emil said. “We have wine. We just need to bring food.”

The wine tasting

The 90-minute tour ended in Milestii Mici’s beautiful tasting room. While two men dressed in traditional clothes serenaded us with an accordion and violin, we tasted three wines: a 2023 Riesling, a very easy drink tasting of apple; a 2021 Merlot, explosive flavors of cherries and plums; a Muscat dessert wine which tasted like a honey caramel milkshake, way too sweet for me.

Later that night, I returned to the Great National Assembly Square. I finished my 12 glasses and watched a Moldovan hard rock band named Zdob si Zdub bounce around with the crowd of thousands swaying to the beat.

I couldn’t understand the lyrics but the violent music made me think of destruction, sex, revolts, typical heavy metal themes. Asked a young Moldovan what they sang about.

“Our culture, our heritage,” he said.

I raised my plastic wine glass for the last time.

Noroc!

If you’re thinking of going …

How to get there: Numerous airlines fly direct to Chisinau. WizzAir flies from London-Luton for €38 one way. I paid $95 one way from Rome.

Where to stay: Apartment on Street Stefan cel Mare, Bulevardul Stefan cel Mare 132, 372-787-78878. Spacious three-room apartment in the heart of Chisinau. I paid €84 for two nights.

Where to eat: La Placinte, Dacia Blvd. 30/1, 373-222-11211, https://laplacinte.md/, 10 a.m-10 p.m. It’s a chain but the place to go for an introduction to Moldovan cuisine. Every national dish is on the expansive menu, including excellent salads and soups. Try the signature cireasa placinte, a layered pie filled with cherries and poppies. Price: €3.50.

Where to go: Milestii Mici winery, Milestii Mici village, 373-671-21-121, https://www.milestii-mici.md/ro/, turism@milestii-mici.md, 10 a.m.-6 p.m. Monday-Thursday, 10 a.m.-7 p.m. Friday-Sunday, €45 guided tour (not including transportation from Chisinau).

When to go: Summers aren’t terribly hot, averaging a high in the low 80s. January is cold, 24-34. When I visited this month it was in the 50s with one major rainstorm and some drizzle.

For more information: Moldova Tourist Information Center, N. Iorga 21, https://moldova.travel/, office@turism.gov.md., 10 a.m.-7 p.m. Monday-Friday, 10 a.m.-3 p.m. Saturday.

Next: Life in rural Moldova

October 23, 2024 @ 10:45 am

Thanks for another entertaining and informative article, John! I doubt I’ll ever make it to Moldova, but I’m glad you were able to go and report back the good news. I’ll definitely have to prod the local wine stores near where I live in Japan to import some of these wines.

Please keep up the good work!

October 23, 2024 @ 11:04 am

Thanks, Tom. You may have to go to China. They’re one of Moldova’s top export customers. How’s life in Japan?