Normandy and July 4th: A riveting walk through the bloody World War II battle that changed the world

(This is the first of a three-blog series on Normandy.)

BAYEUX, France – Celebrating the Fourth of July as an American expat overseas can be an isolating experience. I live in Rome. My girlfriend’s father was 8 years old in 1944 when he ran to Rome’s Historical Center and picked up chocolate bars American soldiers threw from their vehicles as they rolled through town after liberating the city.

Still, Italy doesn’t do anything special for us. No fireworks. No parades. Some July Fourths I’d go up the hill to the American University of Rome which would have a celebration, complete with American hotdogs and burgers. But what Italians do lasts 365 days a year. They have a never-ending appreciation for the U,S. and the Allied Forces saving Italy from Mussolini and the Nazis.

That’s enough. I have never been much into the Fourth of July. I loved the backyard BBQs back in the U.S. But fireworks bore me. So does the flag waving. I grew up with the Vietnam War and lived through the Iraqi War, two of the biggest atrocities in U.S. history. Forgive me if I don’t hang a U.S. flag out my window in Rome.

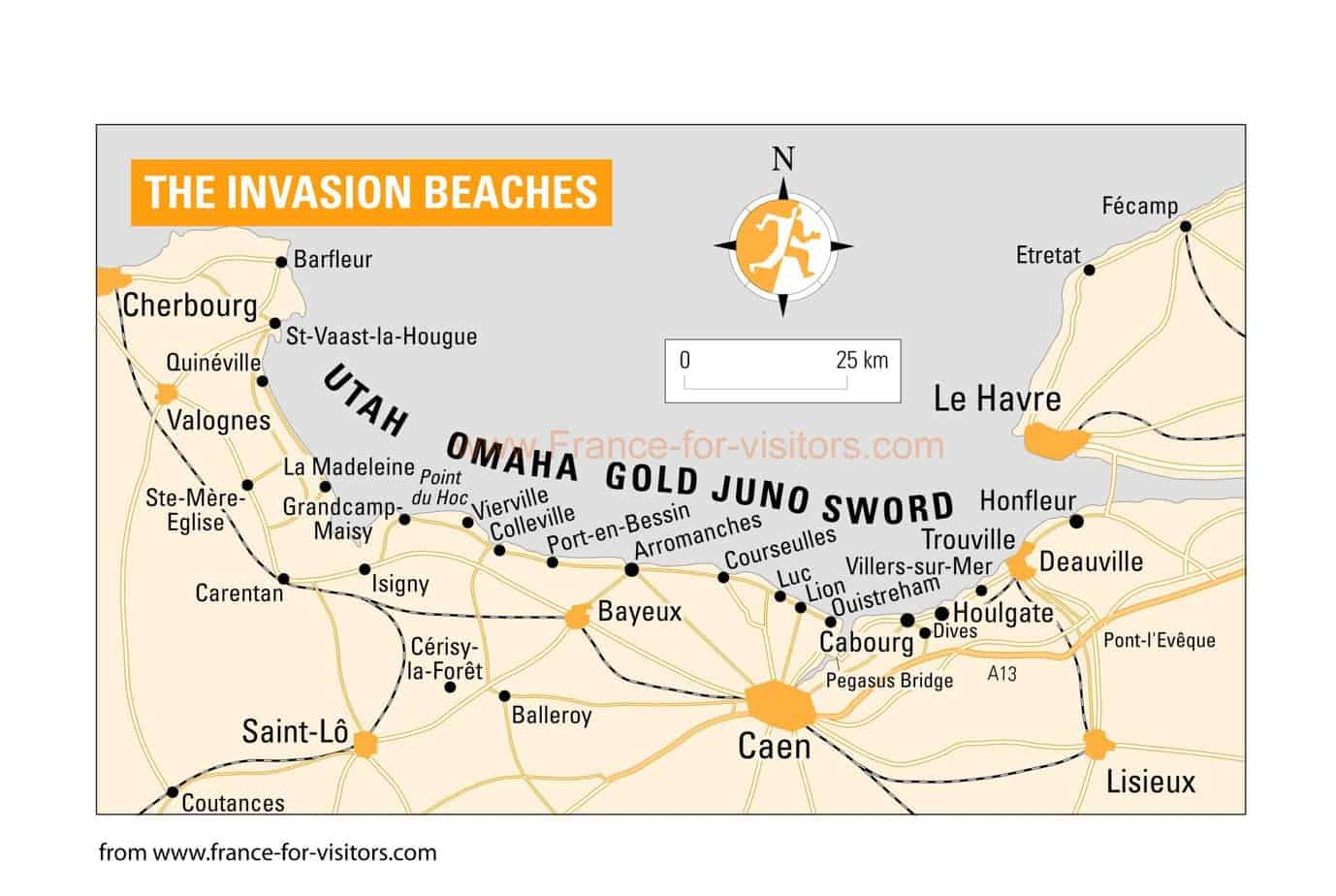

However, two weeks ago I visited the site of arguably the most important day in American military history. I toured the D-Day beaches in Normandy, where on June 6, 1944, Allied troops stormed onto Northern France and turned around World War II in their favor, leaving a trail of their blood and guts and bodies along the way.

I took Marina to Normandy for her birthday. She had a dream to visit Mont Saint-Michel, the Disneyland-like church that rises up from the English Channel on an island off the coast. (Blog coming next Tuesday.) During our sunny week in beautiful Normandy, we took a D-Day tour. It went all afternoon, from the D-Day Museum to the American Cemetery to the five beaches that live in infamy to this day.

So on this July 4th, as you put relish on your hotdog and decide where to watch the fireworks, let me take you through the period in history that must never be forgotten. It was the 100 days of the Normandy Invasion that turned back the greatest threat to Western Civilization in the 20th century.

Here’s RIP to 200,000 Allied casualties.

D-Day Museum

The tour met in Bayeux, a pretty, leafy town of 13,500 people whose ancestors had an up-close-and-personal experience with two major wars. In 1066, the Normans led by William the Conqueror launched their conquest of England from these shores. In the Bayeux Museum, the details can be seen through 58 panels of the Bayeux Tapestry, the world’s most famous embroidery. Bayeux became the capital of liberated France and General Charles De Gaulle came to town for his first speech after liberation.

At a hotel near Bayeux’s train station, we met our guide. Francois was a tall, trim ex-France Army man whose father worked for the French Resistance in World War II. He worked espionage, discovering the number of German troops, weapons and locations to pass on to French command.

I told Francois that I’d been here before. I visited on a cold, gray day in December 1999 when I walked Omaha Beach just below where the Nazis fired away at Allied troops coming on shore. Saving Private Ryan had come out the year before and it sent chills through every blood vein looking up on the dune and seeing what 4,000 men saw before they died.

“It hasn’t changed,” Francois said.

Before this trip, I saw again the riveting opening scene from Private Ryan. Men getting blown away as soon as their amphibious door opened. A man searches around and finally picks up his blown-off arm on the ground. Another holding his intestines overflowing from his open wound. Bodies and blood and dismemberment everywhere.

With this vision on a continual loop in my brain I joined Marina and Francois at the site where it happened. No one else had signed up for the tour that day. We had our own private guide, a personal history lesson. We lucked out. The D-Day Beaches get more than 1 million visitors a year.

We started at the D-Day Museum, in Arromanches-les-Bains, right near Juno Beach where Canadian troops landed that day. In the water we could still see the remains of the artificial harbor the Allies built after the victorious D-Day to land 3,500 vehicles and 24,000 soldiers a day.

The museum, built in 1954 only nine years after the war ended and modernized in April, takes you from the beginning of World War II and Adolf Hitler’s quest to return Germany to the glory it lost in World War I, right to D-Day, known then as Operation Overlord.

We sat through an informative film in English and French then examined thousands of photos with bilingual descriptions. Also on display were weapons, uniforms of Allied forces and Nazis and maps showing the strategy and progress of the winning side. It had screaming front pages from the war including one, ironically, from The Denver Post, where I worked for 23 years.

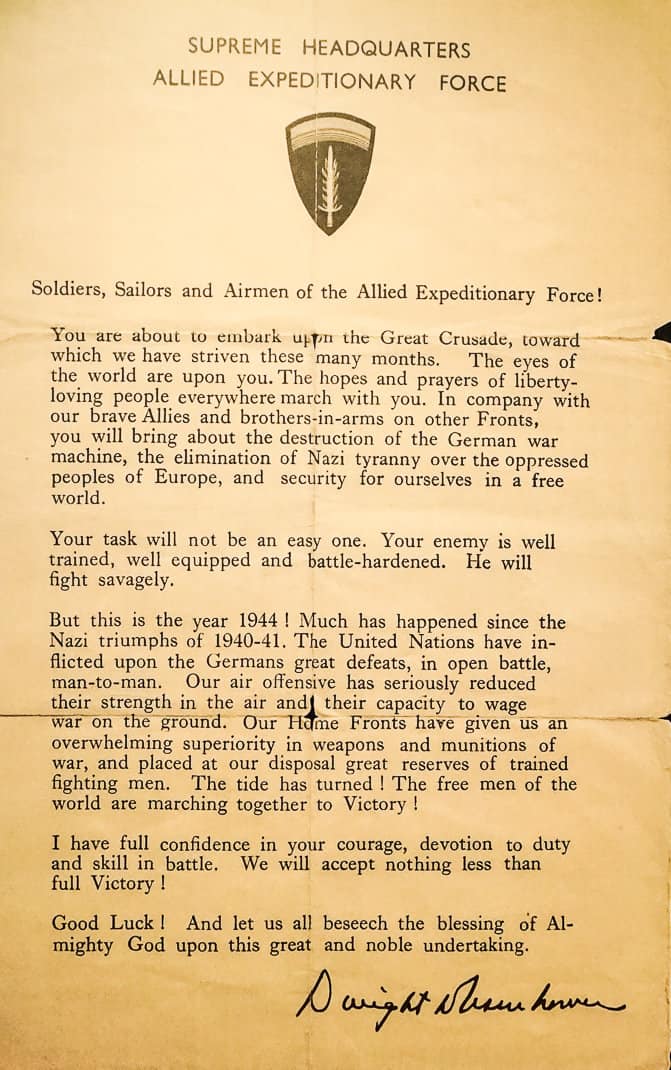

The museum also included a letter, a pep talk, from U.S. President Eisenhower to American troops, saying, “The eyes of the world are upon you.” It was sent June 5, 1944, the day before the invasion.

Interesting facts you probably don’t know:

- During Germany’s occupation of France from 1940-44, it enforced an 8 p.m. curfew, radios were confiscated and beaches were forbidden.

- The invasion was actually planned for June 5, but a storm postponed it a day. Even on the morning of the 6th, the boats had to battle five-foot waves. Some tanks toppled over in the seas, drowning the trapped soldiers inside.

- Two days before the attack, Germans intercepted fake American radio messages that they would attack Calais, 225 miles (375 kilometers) to the northeast and closer to England where the Allies were based. The Germans didn’t think the Allied forces would attack the 50-mile (90-kilometer) beach in Normandy, thinking it was too obvious.

American Cemetery

A short drive led us to the Normandy American Cemetery & Memorial in Colleville-sur-Mer. If the museum’s detailed history of the bloody invasion doesn’t hit you, seeing an endless landscape of tombstones will. In a field of green grass that looks like Augusta fairways are 9,387 graves. They are lined up seemingly all the way to the horizon.

I walked around them and each one had a name, a battalion, a home state and date of death. From Maine to Hawaii and every state in between, the war didn’t discriminate. The Jewish soldiers had Stars of David over their tombs. Others whose identities couldn’t be found said simply, “Here rests in honored glory A COMRADE IN ARMS known but to God.”

I saw the cemetery in ‘99. What I hadn’t seen was the Memorial to the Missing Soldier. It’s a huge white wall listing 1,557 names of soldiers missing from the battle. A blue star is placed next to names of soldiers whose corpses were found after the wall was built in 1954.

Francois pointed out a metal plate in the ground of the memorial which features two huge maps of the invasion’s course. It’s a time capsule containing news articles placed underground on June 6, 1944. It won’t be opened until June 6, 2044 on the 100-year anniversary.

Interesting facts you probably dodn’t know:

- The five beaches suffered 10,000 casualties on June 6. That included 4,000 dead, 3,000 missing and 3,000 injured. Omaha Beach made up 40 percent of all casualties.

- June 6 changed the course of the war but it did not end it. By the end of Operation Overload on Aug. 30 when the Germans retreated, Allied Forces had 209,000 casualties. The Germans suffered 290,000.

- To thwart the invasion by sea, the Germans placed dozens of large iron crosses in the sea to prevent boats from getting close to the beach. The U.S. first sent engineers in on the night of June 5 to destroy them.

The beaches

I’m not a big weather guy. Unless I’m on a beach, it could rain and hail all day and I won’t care. But the weather during our week in Normandy was right out of a tourist brochure: 72 degrees with a cool breeze coming off the sea.

On Gold Beach, we saw a young couple holding a paddleboard and a youth with a kayak. They were walking the same sand that 79 years ago the British 50th Infantry landed shortly after the Americans hit Omaha. Today Normandy’s beaches have the fine gold sand of the Mediterranean if the sea is still only 66 degrees Fahrenheit (19 Celcius).

People sunbathed. Others jogged. All the while hovering above them were German anti-aircraft guns and bunkers left from their losing battle. Francois led us around the cliffs high above the beaches. Every couple of minutes we’d pass huge steel-reinforced concrete machine gun bunkers, complete with leftover artillery.

The bunkers were complete with storage areas and ventilation to let out the smoke that filled the room after every shot. I asked Francois how they hoped to hit ships in the sea from so far away. He said if they shot enough times, eventually they hit targets.

In between bunkers were giant holes in the grass. They could pass for unfilled sandtraps on a golf course – except ones that were 20 feet deep. These are where bombs hit, indenting the earth forever. Some were big enough to park a boat.

“If you want a swimming pool in your garden, just order a bomb,” Francois said in a bit of gallows humor much appreciated on this dark day of ghoulish reflection.

We eventually made it to Omaha Beach where the strip of sand is narrower and the cliffs are closer. I remember my trip in ‘99 when standing on the beach and looking up, it appeared exactly as the cameras depicted what soldiers saw in Private Ryan.

“Forget it,” Francois corrected me. “It was filmed in Ireland.”

The beach has magnificent sculptures such as one of a soldier dragging an injured comrade to safety. Another built in 2004 is a series of tall pieces of steel in various shapes and angles. It’s entitled “Braves” and on the accompanying plaque, French sculptor Anilore Banon wrote it represents the wings of hope, rise and freedom and the wings of fraternity.

“On June 6th, 1944, these men were more than soldiers. They were our brothers,” she wrote.

Interesting facts you probably don’t know:

- Before the war, this area had a beautiful resort overlooking the sea called La Plage D’or. The Germans had it leveled so they had an unobstructed view of incoming boats. The area has a few hotels and seafood restaurants today.

- The Allied Forces sailed from England to Normandy. The journey took seven hours in rough seas. Imagine the seasickness. Imagine the tension. Imagine thinking this will be the last day of your life.

- The invasion of the five beaches consisted of six amphibious divisions, 6,000 boats,13,000 airplanes and 45,000 troops.

Cliffs of Pointe du Hoc

Francois drove us farther down the coast where the cliff seemed higher and the beach seemed narrower. Pointe du Hoc, just west of Omaha Beach, has a long strip of pebbly beach backed by a tall, horizontal limestone cliff covered with green shrubs and bushes.

In 1944, atop the cliff was a German military camp. It included a huge bunker with a machine gun turret, barracks and a tunnel that snaked its way down the coast. It is where 225 Army Rangers hit the beach, threw grappling hooks to the top of the cliff and climbed up 115 feet (35 meters) to shock the Germans.

Francois said of the 225 who tried, 150 managed to reach the top. Of those 150, only 90 were healthy enough to fight. However, a couple broke into the bunker and charbroiled Nazis with flamethrowers and grenades. They shot many more.

The bunker is still there although only a concrete slab is where the machine gun turret stood. The Americans were outnumbered but the only bigger weapon in war than guns is surprise.

“The Germans sat there watching for three years,” Francois said. “Suddenly there were 1,000 ships.”

So enjoy your hotdogs, beer and fireworks, my fellow Americans. Without Normandy, who knows what you’d be eating today.

If you’re thinking of going …

How to get there: The closest airport to Bayeux is Caen, 12 miles (20 kilometers) to the east. However, the connection from Paris to Caen is expensive. It’s cheaper to fly to Paris’ Charles De Gaulle Airport and take the train 2 ½ hours to Bayeux for $30-$60. The bus from Caen is 15 minutes and $6-$13.

How to go there: Normandy Tours, 33-31-92-1070, www.normandy-landing-tours.com, info@normandy-landing-tour.com, 27 Place de la Gare, Bayeux. Excellent tours offered in morning and afternoon for about five hours. I paid €174 for two.

When to go: Except for Scandinavia, I advise everyone to avoid anywhere in Europe in July and August due to the heat and crowds. But on Normandy’s beaches summers are not hot. Average highs are 69 although it topped 70 on our visit. January temperatures range from 38-46 with lots of rain.

For more information: Bayeux Bessin Tourisme, 33-02-31-51-2828, Pont St-Jean, Bayeux, www.bayeux-bessin-tourisme.com, 9 a.m.-7 p.m. Monday-Saturday, 10 a.m.-1 p.m., 2-6 p.m. Sunday July-August.

July 4, 2023 @ 12:26 pm

My son graduated from West Point in 2012. We celebrated with a trip to Italy. We had a guided tour of Florence/Pisa. The guide brought us to the Florence American Cemetery just south of Florence to visit. It was a solemn and moving experience.

July 7, 2023 @ 2:31 pm

Thanks, Tom. The graveyard in Anzio is pretty moving, too. And Nettuno and …

July 4, 2023 @ 9:52 pm

l’m a Brit living in SoCal – been here since 1980. Married an LA boy. Divorced. Didn’t have any roots left in England so l stayed in SoCal.

l don’t celebrate July 4th (we lost, right. ). That said you’re July 4th piece gave me something to reflect on today.

On a lighter note, l’m going back to Rome in October – this time l’m staying in Ostia and will skip Rome. Flight to Lamezia and down to Tropea. Then a slow meander back up the coast with a week in Ischia – the volcanic pools sound awesome.

Keep your travel blogs coming!

All the best.

July 7, 2023 @ 2:31 pm

Thanks, Linda. You’ll love Ischia. Much better than Capri if not as beautiful. By the way, I made a point to mention the Brits’ and Canadians’ contributions to the Allied Forces.

July 5, 2023 @ 9:10 am

Nice post. Let’s also not forget, in addition to the action on the beaches, the airborne forces of parachute and glider troops that were dropped behind enemy lines while the amphibious assault was occurring. Thank you and RIP.

July 7, 2023 @ 2:26 pm

You’re right, Michael. My guide told me about them. They also sent fake parachutes to confuse the Germans.

July 5, 2023 @ 9:07 pm

Thanks, John. We should never forget the sacrifices made by others for the freedoms we enjoy today.

September 5, 2023 @ 8:55 am

Excellent article John !! Great job on your research and the photos were wonderful. Nothing like a private tour.

Yeah, I have to say, watching the D-Day landings in Saving Private Ryan are difficult to watch. I couldn’t even imagine storming a beach with German MG-42 Machine Guns cutting men to pieces. That kind of bravery Should be remembered.

September 7, 2023 @ 3:52 pm

Thanks, Curtis. It really hits home when you’re standing on the beach and looking up at the cliffs. You can’t see anyone but then, never could the troops when hit the sand.