Northern Turkmenistan: A high cliff, a deep lake and a dry seabed is the full Turkmenistan desert experience

(This is the last of a three-part blog on Turkmenistan.)

TURKMENBASHI, Turkmenistan – For a country that doesn’t care much about tourism, Turkmenistan has natural wonders that would make it a sleeping giant on the world scene.

Of course, they have nothing to do with anything Turkmenistan did. They’re natural wonders. This mysterious, isolated desert country just sat back in the tight grip of Soviet communism and Ma Nature did her thing, dotting the country with beautiful – albeit dangerous – scenery.

Besides the Gates of Hell, the fireball flaming up from a 100-foot pit I chronicled two weeks ago, Turkmenistan has two other natural phenomenons that I experienced during my week exploring last month.

I descended 362 steps and swam in the warm, thermal waters of an underground lake. I also braved vicious winds to stand atop a ledge overlooking a canyon that is only second in vastness and beauty to one I saw in Arizona.

Then again, when Turkmenistan tries to do something tourism related, it screws up. Take this town of Turkmenbashi, the port city former dictator Saparmurat Niyavoz renamed after his nickname and is now a derelict of its former self. Not far away is the ill-conceived tourist island of Avaza, an overblown beach resort that crumbled before and during Covid and has just started to come back.

Let’s just say when it comes to tourism, some of Turkmenistan resembles the USSR circa 1964.

We spent one of our last days driving from the capital of Ashgabat 300 miles (575 kilometers) north toward the Caspian Sea. We went past the city of Arkadag, which Turkmenbashi’s successor, Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow (nicknamed Arkadag, meaning “Protector”), named after himself in 2019.

While Turkmenistan’s Karakum Desert is only slightly larger than the ex-dictators egos, Arkadag looks like a mini Ashgabat. Huge white palaces, gleaming white towers, wide spotless boulevards with little traffic. The biggest difference is the local soccer team, FK Arkadag, which Arkadag formed with the nation’s best players in 2023 and went, ahem, unbeaten and untied its first two league seasons.

Kow-Ata Underground Lake

We finally came across a clearing in the desert. About 200 feet below us, sits an underground thermal lake 235 feet long. The Soviets discovered Kow-Ata Underground Lake in the 1970s and built a long, steep eerily-lit staircase. The sign above the entry had some silly rules, such as the lake is not recommended for people who are “In a drunken state,” “Brokenhearted” or “Entering the cave with explosives.”

I descended precariously into the gaping maw of darkness. The faint light made it look like the entrance to a carnival ride. A ledge near the water allowed us to change into our swimsuits – out in the open as we all couldn’t fit in the four tiny, crude changing rooms.

Our guides warned us that the lake, 8-12 meters deep, isn’t nearly as dangerous as the final rocks down. They’re big, jagged and as slippery as ice. But once in the water, the warm, thermal waters enveloped my bones, feeling the effects of six days of walking in a spacious desert country. The putrid sulphur smell usually associated with thermal baths was at a minimum.

However, Kow-Ata is also known for housing the largest collection of bats in Central Asia. We all scampered back up the stairs before it got dark.

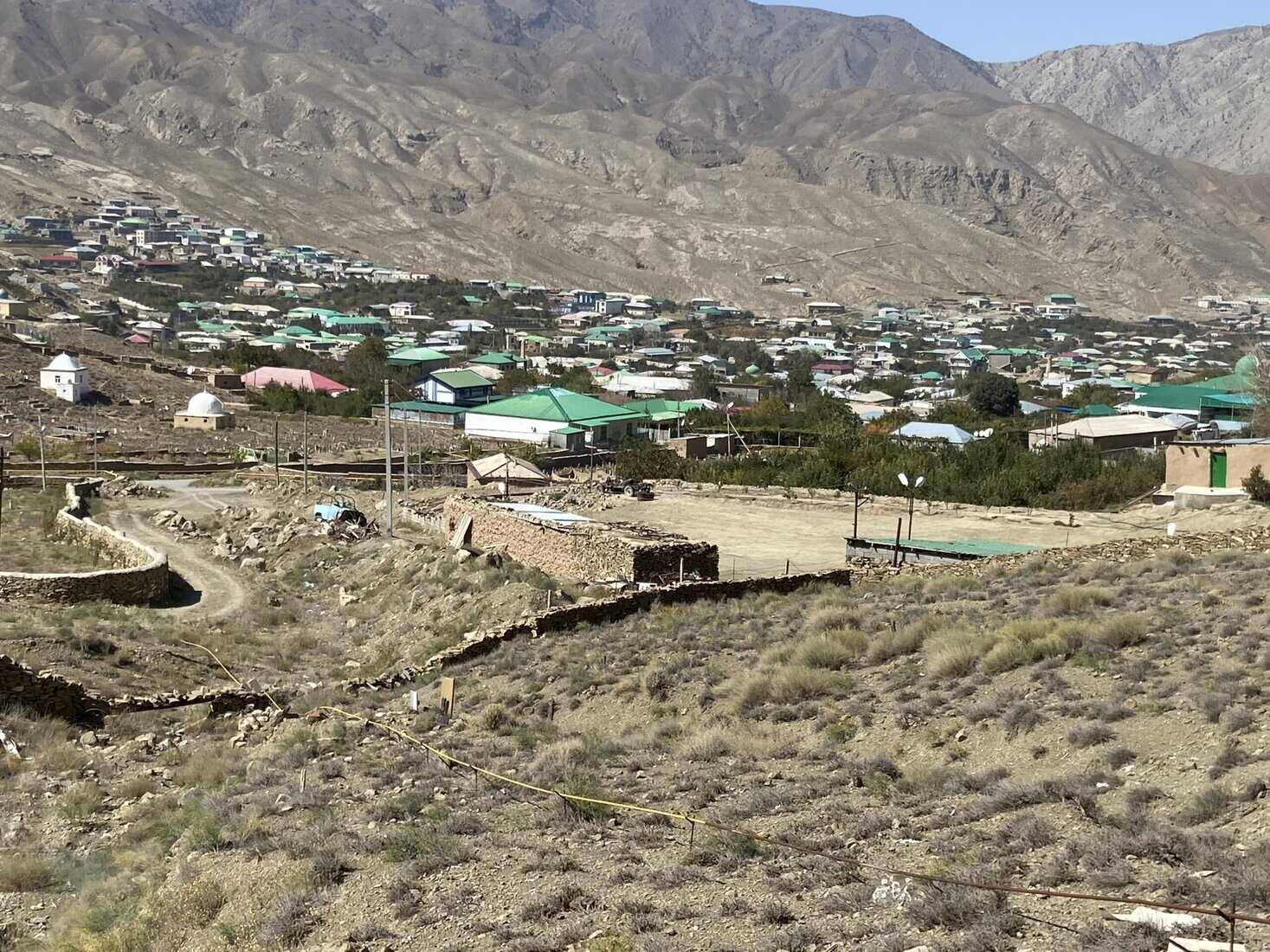

Nokhur

So far, the villages we’ve seen in Turkmenistan have been nothing more than speed bumps on the road. They have one convenience store and children running around on the dusty streets between ramshackle houses.

The town of Nokhur, however, hard on the Iranian border, had a legitimate community feel and a bit of a spooky one. Turkmenistan’s official religion is Islam but it’s unofficially known as an atheist state, a hard carryover from the hardline Soviet days.

But Nokhur is Turkmenistan’s Mecca. It’s the most Islamic town in the country and a pilgrimmage site for Muslims from all over the country.

Each gravestone was adorned with animal horns. Ram was the animal of choice but I also saw antelope horns, all resting atop small stone graves like odd, little hats.

According to Eilidh Crowley, our learned guide with Saiga Tours, each Turkmen has a spirit animal. Many chose a ram which run wild in the surrounding hills. Placing its horns on your grave helps ensure your spirit will go to paradise.

Nokhur’s main feature is a massive sycamore tree that dates to the 10th century. So huge, you can walk inside and stare up at the towering skylight. This town of 9,000 was about the only one in Turkmenistan allowed to practice Islam during Soviet times. Today, alcohol is still banned.

What Nokhur does have is spices. Turkmenistan has 1,000 different herbs used for medicinal purposes and many are displayed in multicolor rows next to the sacred tree. Lavender. Yandak. Ramasko. Various teas. It all smelled like walking through the middle of an open spice rack.

Yangykala Crater

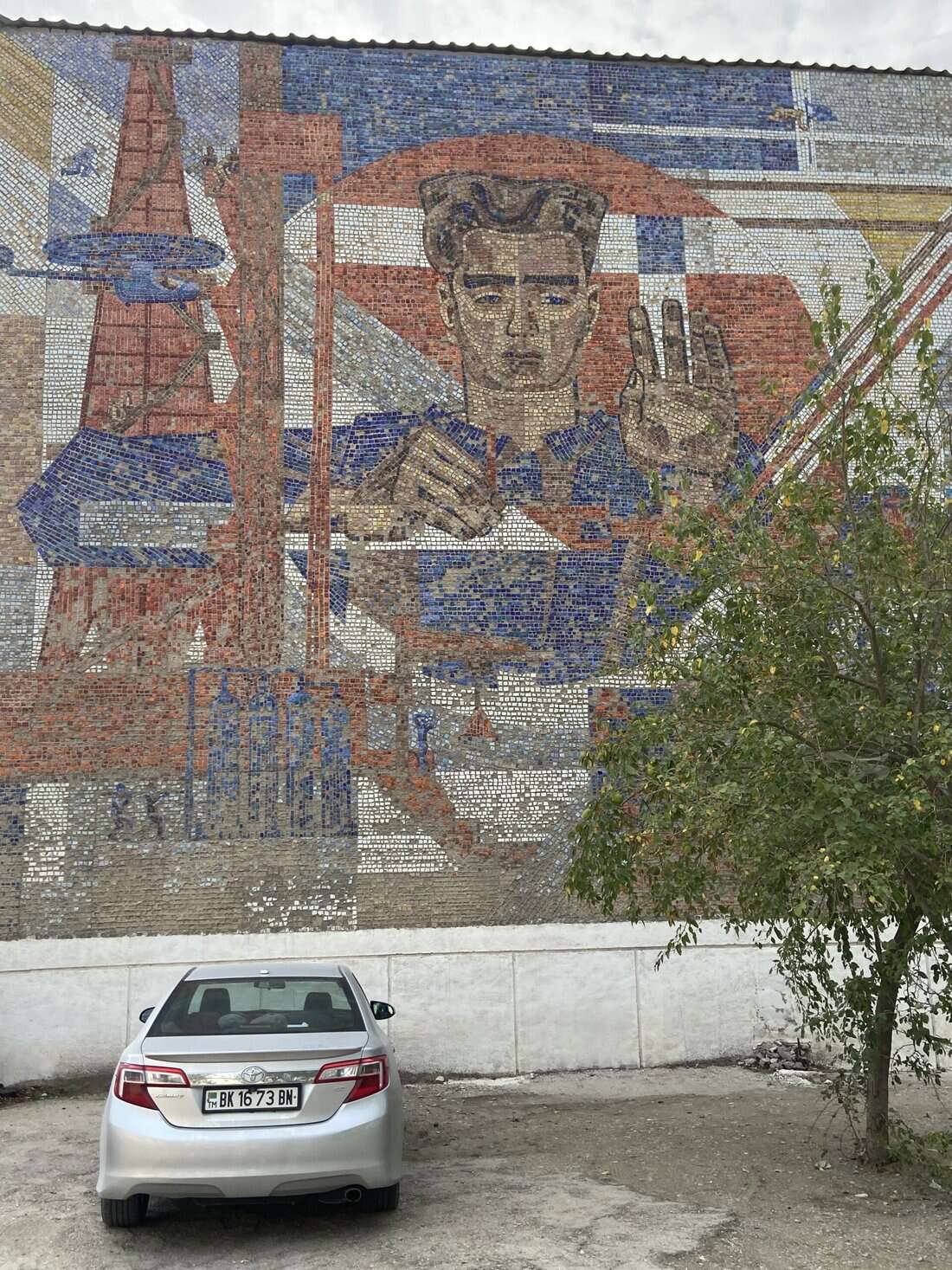

We crashed for the night in Balkanabat, a dreary city of about 140,000 lined with Soviet-style block apartment buildings (some featuring remarkable artwork on the walls) and anchored by a huge gold statue of Turkmenbashi, holding his ubiquitous autobiography and coat over his shoulder, like a Roman emperor.

We stayed in the fairly luxurious Hotel Nebitci, built in the 1940s for oil and gas workers.. Despite a modernized, round lobby and artsy fountain, I thought we were the only ones in the hotel.

This is where Turkmenistan tightens its control. Ashgabat is the only place in the country where you can walk without an accompanying guide. We’re told not to stray from ours as we did an evening stroll to a supermarket brimming with spices and posse of young, eager workers.

The next morning we continued north through a deep, barren desert. We drove for an hour on a straight one-lane road that turned into a scary two lane when a rare car approached. We saw nothing but wild camels and sand. Lots of sand. A ratty miniature basketball court had crooked rims and no nets with a backdrop of sand dunes.

We stopped at a rundown snack shop where two young boys and a girl played on cement steps. A dog pulled a piece of chocolate from a garbage bucket and ate it. We’re told not to pet him. He has fleas.

After another 90-minute drive, we came up to the top of a ridge. There, laying out for us like a beautiful Turkmen carpet, was Yangykala Canyon. It was a deep, deep canyon hundreds of meters down with pinkish cliffs that stretched to the horizon. Tall ridges lined the bottom like playing cards. An orange tint covered the floor.

It was a beautiful panoramic view with dramatic dropoffs on all sides. We were at a spot called Crocodile Mouth, named for a long outdrop of rock over another one about five meters below. If you fell, you could survive if you landed on that ledge but your momentum could send you tumbling into the rocks thousands of meters below.

So with a wicked wind that made it difficult to stand, what a wonderful idea would it be to take turns standing at the edge of the rock for photo ops?

The shot of me looking out at the canyon with it all laid out forever will be on my wall some day. I did not take a photo of me with my legs hanging over the edge or doing yoga poses as some did.

What we were looking at was once the ocean floor. About 100 million years ago this whole area was covered with ocean, said our Turkmen guide, Serdar Varlamov. The tectonic plates moved and the oceans were disturbed. They receded, leaving what we saw below us. The grounds were covered with fossilized seashells.

The wind made me cold for the first time all week. It also kept me from getting too close to the edge. I asked one guy who had his feet hanging off how far was it to the canyon floor.

“I don’t know,” he said. “I didn’t look down.”

Turkmenbashi

TurkmenbashI is an example of a tourist experiment that went south. It used to be called Kasvavos, “Red City” in Russian. It was believed that when the sun sets, the water turns red. That’s when it had water.

We checked into our Yyldyz Hotel, a blue and white tower built in 2012 that you can see from all over town. It was once a seaside hotel. No more. Over the years, the Caspian Sea has receded about a kilometer. After checking in, we all walked across the highway to the sea.

And kept walking and walking.

Across a cracked, hardened seabed we passed through tufts of tall grass until we reached some mudflats that caked my Merrell shoes. This port, opened to much fanfare in 2018, is now too shallow to do the expected annual commerce of 17 million tons of cargo. Ships are now being diverted to the old port two kilometers away.

Down the beach 16 kilometers (10 miles) across the sea on a peninsula we saw the faint light of blue neon. This is Avaza, the beach town resort Turkmenistan tried to create and what we were supposed to visit.

It was built in 2009 and adorned with the ubiquitous Turkmenbashi photo that formed a total eclipse of one hotel. In Turkmen fashion, they built a string of hotels ostentatious in their shape. Two were built in the shape of ships, another like a flag, another like a star. According to Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, each hotel cost an estimated $40 million-$50 million. The hotels had a capacity, Eilidh said, of 1 million visitors.

The government felt Turkmen would go there for holiday. Saida Tours tried.

“It was disastrous,° Eilidh said. °They look nice from the outside but inside nothing worked. Stained carpets. Toilet seats falling off. No restaurant options. No shops.”

Then Covid hit. The country closed for three years.

“When they came back, the first guests were us in April 2023,” she said. “They realized we’d be there not to enjoy the facilities but to laugh at the absurdity of it all.”

Suddenly they closed it to foreign tourists saying it was for renovation. They hoped it would open for peak season, May to October, and that it would open last year. It didn’t. At the end of 2024, the Ministry of Tourism folded and went under the Ministry of Culture. The tourism department had a new head and Saiga hoped it would change.

It hasn’t. We were denied entry. Now they’re annually getting about 150,000 guests who wonder why it’s called a beach resort. The receding sea is 30 meters away. In between it’s just sand and stone.

In a way, standing on a barren sea bed looking at the faint light of a struggling tourist zone was a highlight of Turkmenistan. It represents the dichotomy of a country resisting 21st century emphasis on tourism. I came away with the feeling of being one of the few in the world to see such dramatic sights, to experience a culture that experiences few others.

Is Turkmenistan worth the hassle, worth the group travel, worth the scrutiny and paranoia? Absolutely. It’s what makes Turkmenistan what it is. It’s a country modernizing for the future but stuck in the past, like that weird uncle who buys a fancy car but still yells at neighbors to get off his lawn.

Let’s see how long their pressure gas reserves last. If they don’t and tourism remains in the fetal position, the desert I just rode through will seem even drier.

If you’re thinking of going …

How to go there: Independent travel is not allowed. You must go with a Turkmen-sponsored tour company. I used Saiga Tours, www.saigatours.com. The Australian-based company specializes in Central Asia but also runs tours to the Middle East, Afghanistan, Pakistan and North Korea. They handle everything from the visa to the sightseeing.They are excellent. The Gates of Hell were part of Saiga’s Turkmenistan Independence Day Tour. I paid $1,715 for seven days including airport transfers, accommodations and knowledgeable, frank guides.

How to get there: Flights go to Ashgabat direct from Istanbul, Moscow, Dubai, Frankfurt and Almaty, Kazakhstan, among others in Asia. The four-hour, round-trip flight from Istanbul starts at €580.

Where to eat: Tuncha Cafe, on Oguzhan Kocesi road near Ashgabat’s hippodrome. I paid about $4 for a big plate of plov, Turkmenistan’s signature dish of rice, meat, carrots and onions, a Turkish salad and a soft drink.

When to go: Saiga runs various tours to Turkmenistan all year round. The weather during my last week in September and first week in October was the best I’ve ever experienced overseas: high 70s-low 80s, dry with a cool breeze. I was never hot; I was never cold. In summer it can reach 120 degrees (50 celsius).

For more information: Turkmenistan Ministry of Culture, 993-12-44-2222.

November 4, 2025 @ 7:12 pm

Thank you, John. What an interesting series! This is truly armchair travel as it’s a country few people will see and experience.

November 4, 2025 @ 10:30 pm

Thank you, Kathy. Armchair travel is also dying, succumbing to quick hits and travel tips. I’m glad you enjoyed it. I’m glad there still is an audience out there.

November 5, 2025 @ 4:56 am

John,

I wanted to express my gratitude for the opportunity to learn about a country I previously knew nothing about. Your observations and insights provided me with a deeper understanding of Turkmenistan and its rich history.

Even though I may never have the chance to visit, your vivid descriptions have left a lasting impression on me. I truly appreciate you sharing your experiences with all of us.

November 5, 2025 @ 9:41 am

Thanks, Marc. You’re very kind. I hope I can promote the value of travel, especially to places few people know. I always judge countries by their people and the Turkmen make up for all the atrocities their leaders have done.