Pasta with grandma: NonnaLive gives tourists a taste of dying art of cooking pasta by hand

PALOMBARA SABINA, Italy – Chiara Leone and Chiara Nicolanti are two 38-year-old Italians who grew up with the aromas and tastes few Italian children will ever know. Fresh tomato sauce. Roasted garlic. Floured pasta sheets covering the kitchen table.

Their grandmothers, rolling pins in hand and covered with flour, would let them watch the art of pasta making with wide eyes and growling stomachs.

“Handmade pasta is the symbol of a Sunday lunch with the family,” Leone said. “Now people go to restaurants.”

The changing role of the Italian woman in a country riddled with recession has made making pasta by hand a dying art in Italy, like buskers playing the mandolin on street corners.

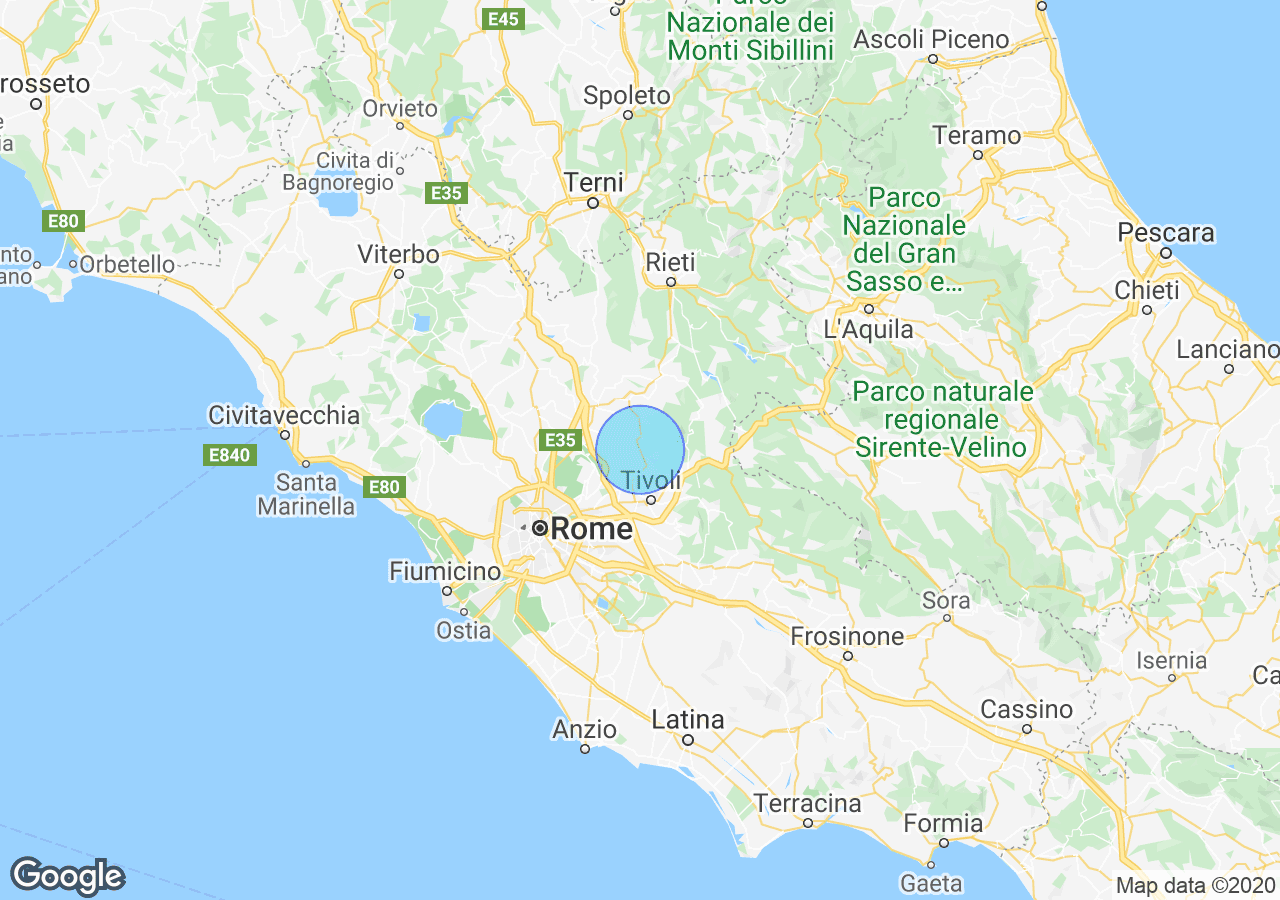

The two Chiaras did something about it. Eight years ago they started NonnaLive, a company that employs 15 grandmothers, mostly from the village of Palombara Sabina 30 miles (55 kilometers) northeast of Rome, to teach tourists how to make pasta by hand.

The business has exploded. Twice daily classes are teaching 5,000 guests a year. Classes have expanded to Paris, the United States and three cruise lines. They were featured in the New York Times and Good Morning America.

I discovered it two years ago when Marina and I went to Palombara Sabina to chronicle the picturesque hilltown for TraveLazio, our blog dedicated to day trips from Rome. What we found was a group of nine village grandmothers overjoyed that people from Sydney to San Diego wanted to learn how to make pasta instead of buying a box of Barilla.

Full disclosure: I wound up taking a class and writing the story in the New York Times.

“The woman is the figure that leads the family and brings the family together,” said Angela Curci, one of the grandmothers. “Without the woman, it is difficult. How do women do it? By making food. When I see that women don’t have time anymore – they’re always going to supermarkets – something is missing.”

Changing Italian woman

Pasta in Italy can be traced back to the 4th century B.C. But it wasn’t until the 17th century when mechanical presses arrived that pasta became part of Italians’ common diet. In 1906 an Italian immigrant in Cleveland named Angelo Vitantonio invented a machine that rolled and cut pasta much faster by the turn of a handle.

Today Italians eat an average of about 50 pounds of pasta per person per year, the most in the world. Pasta sales in Italy last year totalled more than €4 billion ($4.6 billion).

“Everything changed,” said Angela De Paolis from Team Grandmother. “No one cooks (by hand) anymore. Every woman has long nails.”

Women’s role in the Italian home changed. The modern Italian woman has moved from the kitchen to the office. Even though Italy’s employment rate for women is the lowest in the European Union at 52.5 percent, it was only 35.1 percent in 1980.

In fact, women could not work public jobs until 1963. Then came more rights: divorce in 1970, birth control in 1971 and abortion in 1978.

Meanwhile, Italy’s birth rate dropped from 18.6 births per thousand people in 1950 to 6.3 this year. Many Italian women began realizing they could afford a good life without a family.

“There’s no more staying at home with kids,” said Leone, who joined Nicolanti’s company after her own grandmother died four years ago. “You can’t afford to have one person working at home. It’s not like before. You don’t have time to cook for your family. So it’s really difficult to find someone who makes homemade pasta during the week. The generation of my parents is when it changed, the 1960s. My mom stopped making pasta.

“They missed one generation – our parents’ generation – and if we don’t take back our grandmothers’ generation, then it’s too late.”

How Pasta With Grandma started

Nicolanti, raised in Palombara Sabina, got the idea nine years ago when she was pregnant. She spent time at her grandmother’s home in town and remembered her younger days when she’d visit while her Grandma Nerina made pasta. Nerina talked about her mother and her grandmother.

“She made me feel like my story wasn’t just about me,” Nicolanti said. “I was part of a chain. And I didn’t want to be the weak one. I wanted to be strong like my grandma.”

During her pregnancy she began making pasta with her. One day she posted a photo on Facebook with the caption, “Hey, who wants to cook with grandma today?”

It went viral.

She received a ton of requests from people around the world and Italy wanting to make pasta with her. Turns out, Nerina wasn’t the only grandmother in town who wanted to pass down the art. Eight others said they’d be happy to do it and, with the promotion backing from AirBnB, they formed a company with the name Handmade Pasta With Grandma.

“They feel special,” Leone said. “They feel they’re in contact with people every day. They’re never alone. It completely changed their life.”

Grandmothers’ views

De Paolis was also a working woman. She and her husband owned a furniture shop in Palombara Sabina for 30 years. But she still found time to make pasta by hand. She kept the Italian tradition of the massive Sunday lunch alive while it faded elsewhere as the art of handmade pasta faded.

“It keeps me company,” she said. “I start making pasta when I’m alone at home. I put some music on and just work, work, work the dough. It relaxes me.

“When the grandkids arrive, they arrive running because they can’t wait to have my pasta: ‘Grandma! Is there pasta for me?’ It makes me feel valuable. I feel like the grandkids need us.”

Homemade pasta is dying in Italy primarily due to time consumption. It is labor intensive. However, Curci disputes it – if you’re good.

“For us, it became so natural to make it by hand that actually it takes more time to get out of the house, go to the supermarket and buy it rather than make it at home,” she said. “Especially the supermarket pasta takes 15 minutes to cook. This takes three minutes so you recuperate the time.

“It’s just a matter of laziness.”

The class

For us 10 rank amateurs and hack cooks from the U.S. and Spain, it took us longer than 15 minutes. It took us two hours. But I learned a lot, such as the less flour you have on your dough the less dough you have all over your hands and arms.

We started with a brief tour of the town. With a population of 13,000, Palombara Sabina sits atop a foothill of the Apennine Mountains. Its narrow, windy cobblestone streets lead up to the 11th century Castello Savelli, now used for weddings and a great view of Rome from its watchtower. Along the way, we saw Grandma Nerina’s famous house where it all began.

They led us to Curci’s spacious home where we sat around a long dining room table.

“They call this Grandma’s gym,” Leone said.

Each person had a rolling board, a long rolling pin, a dough cutter, flour and eggs. We were going to make farfalle, the butterfly shaped pasta; ravioli; and with the leftover dough, fettuccine with fresh tomato sauce.

Curci’s first instructions: 100 grams of flour per egg, enough for one person. If you have a dinner party for eight, you use 800 grams and eight eggs. Sounded simple enough.

We mixed all the ingredients into a big doughy ball and Curci showed how to do the ancient technique. We folded the pasta around the rolling pin to allow the dough to have a thickness and consistency. I mixed it, kneaded it, filled it, smoothed it, wrapped it around the rolling pin and rolled it some more.

I cut the dough into squares and pinched each piece to form the butterfly shape. However, I had more dough on my hands than I did on the rolling board. Some of my pasta looked like butterflies. Others looked like vampires.

“Mamma mia!” Curci said. “Watch me.”

Soon I had a whole collection of farfalle pasta which I topped with a sauce of olive oil, almonds and crushed garlic. She popped it in the oven and in, yes, three minutes, it came out piping hot and oh, so good.

The constant chatter among us amateurs turned to silence as we ate fresh, homemade pasta as good as any trattoria we’d find in Rome.

I then cut long strips of dough and placed a mixture of ricotta and spinach, then folded the dough over the fillings, sealed the edges and cut the strip into squares. Instant ravioli. Fresh. Homemade. Even if you don’t like spinach, as I do not, it was delicious.

“Even in Palombara people stopped making pasta,” Curci said. “With Pasta With Grandma, we are recreating the beauty of it.”

Ships ahoy with grandma

Palombara Sabina is easy to reach from Rome. From Rome’s Trastevere station, regular trains take 50 minutes to reach the nearest train station at Painabella di Montelibretti where the Chiaras pick up customers and drive them 10 minutes to the center.

However, many potential customers come from cruise ships that dock at Civitavecchia, Rome’s main cruise ship port 90 minutes from Palombara. The women had an idea.

Instead of bringing cruise ship passengers to grandma, take grandma to the cruise ships. This summer they just finished runs on the Equinox, Constellation and Ascent cruise lines which came to Italy and Greece from Miami, Fort Lauderdale and Tampa.

Each ship had two grandmothers and a translator.

“I didn’t know if a grandmother could stay for 18 days on an ocean,” Nicolanti said. “It’s too much. I asked the nonne if it’s something they’re willing to do. They said, ‘Yeah, let’s go! I want to see the world!ì’”

The lessons on board and in the grandmothers’ home run about €100. The ships run between the beginning of June to mid-August and it will return by popular demand.

The grandmothers’.

“It was too much fun to see the world through their eyes,” Nicolanti said. “Some had never left their village before. Oh, my God, it was so much fun! Trying different food. American vessels. See them try sushi, paella.”

Nicolanti hasn’t stopped. In December she published a book about her grandmother, including recipes, entitled Behind Her Hands. In it, she describes how the first meal Grandma Nerina gave her as a child was pastina al formaggino, a creamy dish made with small pasta pieces, vegetable broth and crushed sweet cheese.

Her grandmother died two years ago. She became too ill to feed herself, so Nicolanti fed her instead. The last meal she gave her?

Pastina al formaggino.

It’s that kind of up-close-and-personal touch that is driving NonnaLive. My patience and total lack of cooking skill prevented me from trying the recipe from home. But I get the appeal. It’s a way for people to step away from their computer and do something with their hands.

Plus, it tastes pretty good.

“So wherever you go in the world,” Nicolanti said, “there’s a grandma waiting for you, feeding you until you explode.”

If you’re thinking of going …

Contact: www.nonnalive.com, chiara@nonnalive.com

Class schedule: 9:30 a.m., 2:30 p.m. Monday-Friday, 12:30 p.m., 2:30 p.m. Saturday-Sunday.

Price: €100 per person, children €50.