Romania and Ceausescu: Dictatorship left scars on a bustling nation and a warning to the U.S.

(This is the fourth in a series on Moldova, Romania and Transnistria.)

BUCHAREST, Romania – By the end of today, the United States may elect a dictator.

As Donald Trump ramped up his rhetoric this fall, vowing he would jail political prisoners, deport millions of immigrants and use the military against disloyal Americans, I found myself in a country that experienced a similar dystopian existence.

Romania.

While traveling the country and hearing Romanians’ stories about legendary henchman Nicolae Ceausescu, I couldn’t help but draw the parallel. Yes, Ceausescu was left wing; Trump is right wing. But communist and democratic dictators have similar autocratic traits. To wit, they …

- Trust no one.

- Suppress the media.

- Use the military for their own personal needs.

- Stack the courts.

- Incite fear.

In Romania, where Ceausescu rose from a rural, elementary school dropout to a semi-literate communist leader from 1967-89, his legacy remains today. I lost count of how many Romanians, from taxi drivers to bartenders, told me the exact same thing.

“We had nothing.”

Ceausescu’s legacy

Ceausescu’s legacy is one of inconceivable oppression. He:

- Nearly starved the people while paying off a foreign debt.

- Ordered the military to shoot protesting citizens.

- Had spies in every corner of society, from workplaces to classrooms.

- Made abortion punishable by imprisonment, leading to squalid orphanages, horrific images of which were transmitted around the world.

- Forced citizens to attend public events in his honor, inspired by his visits to North Korea and the leader he admired most, Kim Il-sung.

When I visited Hungary in 1978, oppressed Hungarians told me of all the countries behind the Iron Curtain, Romania was considered the worst. When I finally visited Romania last month, it was hard to fathom the country’s advances.

Bucharest today

I sat at an outside table at the tony Hotel Capitol, built in 1901, eating a piece of cheesecake with berry topping and whipped cream while sipping a nice Romanian Chardonnay. The street, Calea Victoriei, was closed to traffic. Smiling couples rolled baby strollers past a man playing a piano. A light show played on a massive wall across the street.

Down Victoriei, past the huge statue of Carol I, Romania’s first king and national hero, I strolled down Strada Episcopiei. Cute French-style cafes lined the street with decorative chairs and tables outside. French aristocrats set up shop here in the early 1900s in Romania’s golden age, giving Bucharest the nickname “Little Paris. The city spiffed it up after communism fell in 1989. At Cafe’ Chocolat, I sat down for a praline with crunchy nougat and a cappuccino.

Then I saw the price of a cappuccino was 39 leu, about €8, and left, thinking, Yes, Romania has learned all about capitalism.

The country has embraced tourism as much as Ceausescu embraced secrecy. Last year a record 13.7 million people visited Romania, more than doubling the total of 6.1 in 2009.

They’re coming to see more than just Bran Castle. Singhisoara, Transylvania’s “other” site, is so beautiful it was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1999. Iasi, a cute, quaint city full of culture and parks in northern Romania, opened a riveting Iasi Pogrom Museum three years ago. Timisoara and its magnificent historical center was named European Capital of Culture last year. Romania joined the European Union in 2007.

Bucharest itself has gone from a drab, closed East European capital as gray as a gulag to a thriving city full of bustling nightlife, lively street culture and yummy restaurants. Add Romania’s underrated wines, affordable prices and friendly, open people and you have a destination that’s on the bucket list of Europhiles tired of the beaten paths in France, Italy and Spain.

Sure, Bucharest tourism has gone over the top a bit. Its Old Town is a series of touristy bars with barkers outside trying to lure me into places with names like Big Ben Pub where the menu is bigger than the one at Denny’s. A man in a change booth, obviously tired of tourists, responded to my question of how many leu would €100 get me with “Go to the next station!” and walked off. Cab drivers tried charging me €20 for a five-minute ride because they said, “It’s night” or “Private taxi.”

But Bucharest still rocks. It has a different vibe than other European capitals, still growing into its role as a tourist destination. Its restaurants alone are worth visiting. An American friend who lived in both Rome and Bucharest told me, “Italian food is overrated; Romanian food is underrated.”

I won’t go that far, but Bucharest’s restaurants were excellent in their scenery and food quality. Romanian cuisine is heavy. Lots of sausages, meats, stews, soups. For the most authentic Romanian food, I went to Bacania Veche in the Plata Romana neighborhood on the northern edge of the city center. With a romantically lit garden and country decor inside, it’s where my first Romanian meal was pulpa de rata conflata si sos de trufe negre, (candied duck leg in black truffle sauce.)

The next night I went to Caru’ cu Bere, a Bucharest mainstay since 1879 but now packed every night. Once a jazz club, the sprawling restaurant has Neo-Gothic stained glass windows and lamps hanging from brass ceiling chains. Its legendary beer, made in house, was way too light but its “Master’s delight,” glazed pork ribs in beer sauce, featured luscious meat that fell right off the bone.

Afterward I strolled down Vittoriei past bars full of laughter and soccer games on TV, outdoor tables of people sipping wine and eating dessert, lovers holding hands past tastefully lit monuments.

And people were friendly, always willing to talk about the bad old times and the improved new times – with some whining about modern democrat corruption. They were as open as my Lonely Planet Romania & Bulgaria guidebook. Why me?

“You are a foreigner. You may not return in their lives.”

Romania historian weighs in

Speaking was Daniela Popescu, history professor at the University of Bucharest. Communist Romania is one of her specialties. Even though she was born after the Romanian Revolution that toppled communism in 1989, she said her parents took the aftereffects of life under communism and passed them on to her.

“The constant fear that you would be judged and punished for your opinion,” she said. “I remember when I was in school my mother always told me, ‘Please be careful what you are saying in school about our family. Don’t tell anything to anyone. Don’t talk to people you don’t know. Keep it between us.’

“It’s this perception that you are never safe. I grew up with this mentality, to always be careful what I am saying. Who is the person I am meeting? Is he or her intending to punish me in some way?”

This was true in other communist countries I’ve visited. Cubans and Hungarians spilled their guts to me as a foreigner. They trusted me. I apparently would’ve made a good communist spy.

Daniela painted a vivid and disturbing picture of life under communism even though she grew up nearly as Western as a girl in Santa Monica. But girls in Santa Monica don’t hear their parents talk about the “old days” like life in Hades.

“Someone like my parents, they were members of the Communist Party but only because they were forced,” she said. “They didn’t have any position. They were ordinary workers. Their living was very hard because they were constantly supervised, even by their colleagues, because each workplace had a representative of the Securitate (Romanian secret police) and they never revealed themselves.”

I asked her of all of Ceausescu’s crimes, what was his worst.

“Each age group, each city, has a different perspective,” she said. “If you ask those people who lived in the ‘60s and ‘70s, some of them will have the impression that communism wasn’t that bad. But if you look at the generation in the ‘80s, most of them hated Ceausescu.

“The peak of Ceausescu’s regime was in the ‘80s and the hardest. There was an economic crisis. You had a card and were limited to buy, say, one bottle of oil or one bread. You had a limit. So many people remember the ‘80s with hatred.”

Ceausesco Mansion

Ceausescu’s old home is at the end of a long tree-lined street in the ritzy north Bucharest neighborhood of Primaverii. The zone is sandwiched between two lakes and filled with stately homes and huge trees. Forty years ago, however, this neighborhood was fenced off and guarded 24-7 by the Securitate. The zone had only six houses.

“And no one knew which house belonged to Ceausescu,” said Victorio, the tour guide. “It was a very well-kept state secret.”

Victorio is only 24. Communism had been dead 11 years by the time he was born. But he is a voracious student of Romanian history and sprinkled his tour with interesting tidbits of one of mankind’s most ruthless leaders of the 20th century. Such as:

- While semi-illiterate, Ceausescu loved chess. He often played his prime minister and foreign minister in his chess room with hand-carved chess pieces. “It was said he was the best chess player in the country,” Victorio said. “But we’ll never know because no one dared to defeat him.”

- He loved peacocks. On a 1975 visit to Japan, he fell for the peacocks that strolled the courtyard of Japan emperor Hirohito. Ceausescu returned to Romania with three pairs. Peacocks still stroll the grounds today.

- In 1979 he developed diabetes and despite his wealth and being one of the few Romanians allowed to travel abroad, his strict diet limited him to only boiled vegetables and fish.

Victorio also mentioned some positive things Ceausescu did. He created housing. He built Bucharest’s subway. When the USSR invaded Czechoslovakia to quell protests in 1968, he would not back the Soviets. Suddenly, the West felt it found an ally in Eastern Europe. Ceausescu was someone it could work with, someone who stood up to Mother Russia.

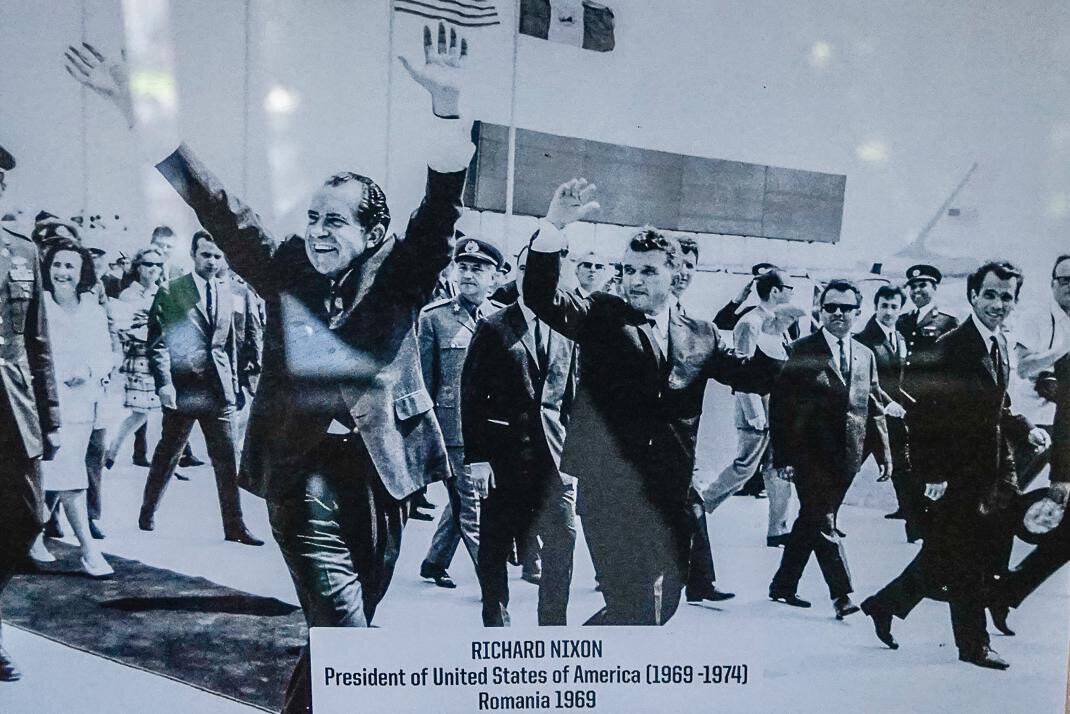

Romania at the time had a massive agricultural industry, a top-ranked aeronautics program and reserves of oil and gas. This place had potential. A corridor running alongside the house show black and white photos of Ceausescu with U.S. presidents Richard Nixon and Jimmy Carter, Israel’s Golda Meir and France’s Charles De Gaulle.

But there are also photos of Ceausescu with the likes of Saddam Hussein, Fidel Castro and Mao Zedong. Also, the most important, is one from 1978 with Kim Il-sung. Ceausescu was so impressed with North Korea’s heavy handed government, he returned to Romania vowing to transform his country from an agricultural power to an industrial giant.

He blew it.

By the 1980s, Ceausescu found his country saddled with massive debt and he exported nearly all of Romania’s produce. Thirty years after being the second-leading food producer in Europe behind France, Romania had people starving in the streets.

All this time he lived in the house that I found myself touring on a sunny October day. Called the Spring Palace when he lived and now simply the Ceausescu Mansion, its entry has a wide staircase under a marble canopy supported by eight marble columns.

The house, built in the mid-60s, is 4,500 square meters covering 80 rooms for him, his three children and his wife Elena, whom he made third in command in the government. Walking through it (no photos allowed) is like touring a royal gift store. There’s the Persian rug from the Shah of Iran, porcelain plates from England’s Queen Elizabeth, Chinese vases from Chairman Mao.

The Winter Garden is a giant window-encased room filled with towering exotic plants watered every Monday. The heated indoor swimming pool is 14 meters long, three meters deep with 1 million pieces of mosaic on the wall featuring images of exotic birds including, yes, peacocks.

Then there’s the “Golden Bathroom.” The couple’s bathroom from the sink to the floor is made of gold.

“The information, of course, is completely false,” Victorio said, “because on the ceiling and in the shower is mosaic and the floor was not gold plated but gold dusted of 7 carats, the cheapest gold available on the market.”

But as one Romanian said when I mentioned it, “It sounds kind of apologetic. Come on, dude. It’s still gold. People were having a hard time. I would wear 7-carat gold.”

By the late ‘80s, starving Romanians had enough. Protests erupted in cities all over the country. Ceausescu, going mad and desperate, ordered his military to fire. More than 1,000 died. On Christmas Day 1989, he and his wife were captured and convicted in a quickie trial. They were then flown via helicopter off the roof of the Central Committee of the Communist Party headquarters.

They were taken to Targoviste, a town 80 miles northwest of Bucharest, and executed by firing squad.

“As Orwell said, ‘Under communism, everyone is equal but some are more equal than others,’” Victorio said. “This house is the best example.”

Palace of Parliament

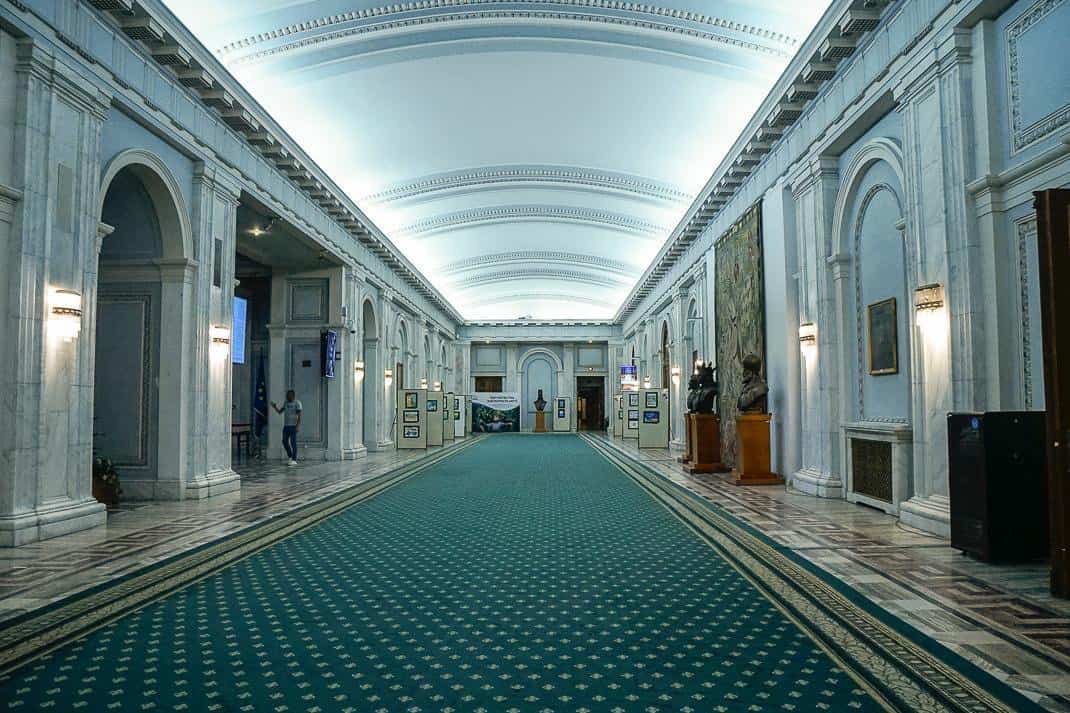

Ceausescu had another palace built but he never got to really enjoy it. In 1983 he wanted an office building as powerful as his own self image. He cleared out dozens of houses on the other side of the Dambovita River from the city center and built a massive complex that dominates the landscape like a castle in the sky.

The Palace of Parliament covers 360,000 square meters, consists of 1,100 rooms over 10 floors and 2,800 chandeliers. It took 700 architects and 4,500 workers to build the Neoclassical structure with 550,000 pounds of concrete, 700,000 pounds of steel and 1 million cubic meters of marble. The cost was $3.2 billion. It’s the second biggest office building in the world after the Pentagon.

However, it wasn’t completed until 1997 and wasn’t really functional until 1994. Ceausescu only used a couple rooms to make some public speeches and write a few letters.

Waiting for our tour to start, I met Francisc Leopold, a 36-year-old waiting to guide his own tour. He hails from Iasi and is living the good life in Romania. It remains relatively cheap. He said you can buy a one-bedroom apartment for €8,000. Rent one for €300 a month.

“Statistically, it’s never been better,” he said.

I told him my visit to the U.S. in July made me believe the U.S. may be the most expensive country in the world.

“That doesn’t mean you have to go to some dictatorship because of that,” he said.

The irony was not lost on me.

I asked him what the biggest advancement Romania has made in his lifetime.

“Joining the EU,” he said. “We have live projects, education, business. It’s all going up.”

The 90-minute tour covered only 5 percent of the building. The first floor alone is 66,000 square meters. We walked down the main hallway that’s as long as two football fields. Connecting to the hallway were 500-square-meter conferences with 14-carat gold leaf chandeliers and oak wood panels. An auditorium seats 600.

When communism fell, so did censorship. Protests over the building erupted.

“People were very upset,” said Dragos, our guide. “The bigger concern in the 1990s was the big inflation transition from a communist economy to an open economy. The loss of jobs. Factories were closing down. It was the biggest inflation we’ve ever had. They were still building this humongous structure which, again, was not demanded by us. We didn’t want it.

“But we got it anyway.”

Some attempts were made to buy it by outsiders, including, he said, “some very prominent billionaires in the United States. Perhaps even a former president of the United States but we don’t have confirmation of that.”

The election

While Romanians continue sipping wine on Victoriei and hiking through the fall colors of Transylvania Tuesday, I will be huddled in my hotel room in London watching the election returns through my fingers like it’s a slasher film. I don’t want to look.

I am not confident. I have little faith in the American people. And after spending more than a week in what was one of the most oppressed societies in the late 20th century, one other emotion has taken over my soul.

Fear.

Next: Transylvania

If you are thinking of going …

How to get there: Many European capitals fly directly to Bucharest. I paid €100 on WizzAir one way from Rome.

Where to stay: Visionapartments, Calea Victorei 38-40, 44-249-3434, https://visionapartments.com/en/locations/bucharest/, info@visionapartments.com. Transformed from an apartment house to a hotel in September 2023, Visionapartments is in the heart of Bucharest with spacious rooms and a nice spa. I paid €254 for three nights.

Where to go: Ceausescu Mansion, Bulevardul Primăverii 50, 40-21-318-0989, https://casaceausescu.ro/en/rezervati-3/, office@palatulprimaverii.ro, 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Tuesday-Sunday, €13 guided tour. Book ahead.

Palace of Parliament, Strada Izvor 2-4, 40-733-558-102, https://cic.cdep.ro/, 9 a.m.-5 p.m. €12 guided tour. Book ahead.

Where to eat: Bacania Veche, Bulevardul Dacia 25, 40-31-229-6672, https://bacaniaveche.ro/bacania-veche-romana, bacaniadinromana@bacaniaveche.ro, noon-10 p.m. Monday-Sunday, 5-10 p.m. Traditional Romanian dishes with mains from €10-€18.

When to go: Like everywhere else in Europe, Bucharest gets crowded in summer where temperatures reach the high 80s. Winter it drops to the mid-20s. In October it was pleasant in the 50s and 60s with little rain.

For more information: Romania Tourism, https://www.romaniatourism.com/.

November 11, 2024 @ 10:46 am

I truly enjoy reading about your travel adventures. You are an excellent writer which makes the stories you pen come alive in my imagination. Your fear regarding the way the USA was going to go regarding the election unfortunately proved to be accurate. As an American I am scared shitless about what is happening to the USA. Count yourself fortunate that you don’t live here anymore. I look forward to your next travel adventure, stay safe:).

November 11, 2024 @ 12:11 pm

Thanks, Victoria. Read tomorrow’s blog. I write about people similar to you trying to move to Italy. The CEO of Expats Living in Rome said her traffic tripled the day after the election.