Uplistsikhe: Hard to pronounce but Republic of Georgia’s 3,000-year-old Cave City is hard to miss

KVAKHVRELI, Georgia – Imagine you’re an archaeologist, and it’s 1957 Soviet Union. You’re digging around on a hill next to a river. The beautiful view of the valley is almost distracting you from your dig.

Suddenly you hit a rock. Dig some more and you find it’s the roof of a cave. It’s not just a cave. It’s a cave big enough for a family of five. Dig some more and you find another cave. Then another. And another. And another.

Soon, you have uncovered what is essentially a cave city covering 40,000 square meters. It’s 12 years after the end of World War II and the USSR has brought along a new war. But the Cold War seems a long way from this massive unveiling, in the foothills of the Caucasus mountains in the small republic of Georgia.

The first caves were created at the beginning of the 1st mellenium B.C. 3,000 years ago. About 2,000 years ago, this hill was one of the major political and pre-Christian religious centers in the area that has traces of inhabitants from the 2nd millennium B.C. It once had a population of 20,000 living in 700 caves. As I walked around the archaeological site earlier this month, I could tell they had a nice life.

A theater. A temple. A pharmacy. Meeting halls. And this being Georgia, the birthplace of wine, it had a huge wine cellar for relaxing after said theater, temple and meeting. The next morning, the pharmacy was probably pretty handy.

The site was named Uplistsikhe. I tried pronouncing it and my face nearly exploded. It’s Georgian for “Castle of the Lord.” It’s also known simply as Cave City.

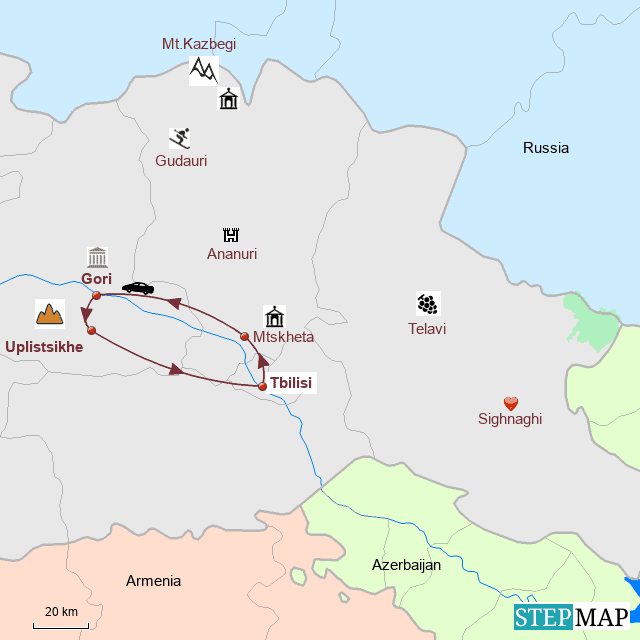

I came on a day trip with other travel bloggers attending the Traverse travel bloggers conference in Tbilisi, Georgia’s capital. Uplistsikhe is 40 miles (76 kilometers) northwest of Tbilisi and the drive through the Georgian countryside was nearly as entertaining as the site itself.

The journey from Tbilisi

Lela Giorgadze, sporting a Ph. D in tourism, sprinkled the rides with tidbits about Georgia’s situation two generations after archaeologists put Uplistsikhe on the international map. We crawled out of the capital in traffic that has become a growing problem. But once we escaped the city limits, rural Georgia became a kaleidoscope of history covering two millennia.

We passed a small monastery of yellow stone with an octagonal shaped dome. Jvari Monastery, built in the 6th century, was the only monastery the Soviets didn’t destroy when they ruled Georgia for 70 years. It’s located in Mtskheta, Georgia’s original capital from 6th century B.C.-5th century A.D. and where Christianity was declared the country’s official language in 337 A.D.

Lela said Mtskheta is called the Jerusalem of Georgia and “If you go there three times to pray, you’ve been to Jerusalem once.”

We rode along rough roads with the Caucuses’ snow-sprinkled foothills off in the distance. Villages of red-roofed houses came upon us. These housed the refugees from South Ossetia, the breakaway Soviet region on the Georgia-Russian border now guarded by Russian soldiers. More than 300,000 Georgians were run out of South Ossetia and have not been allowed back in.

Neither can anyone else. You can’t get in; you certainly can’t get out. I was at the border on my first trip to Georgia in 2018, reporter’s notepad in hand. I came face to face with a Russian guard. If looks could kill, I’d be writing this posthumously.

Lela talked about modern Russian refugees who came into Georgia after Vladimir Putin invaded Ukraine two years ago. It has caused tension among the locals.

“They cross the border and say, ‘Oh, Putin is awful,’” Lela said. “But here (they) say Russia should grant (them) more territory and they start arguing, ‘Putin’s a cool guy.’”

Joseph Stalin

Then we learned about arguably the most awful Russian. We passed through a pleasant town with trees lining wide boulevards and homes that weren’t quite as awful as ones we’ve passed. This was Gori, home to Joseph Stalin, Georgia’s native son.

He was born in this town six miles (10 kilometers) from Uplistsikhe. While he moved to Tbilisi when he was 15, Gori still claims him, albeit somewhat uncomfortably. How do you honor a local who murdered 6 million of his own people? You turn his modest wood-and-brick childhood home into a museum and put the personal railway car he traveled around the Soviet Union in front of it.

We didn’t stop to tour the Stalin Museum but it charts his climb from the Gori church school he attended through his rise in the USSR to the end of World War II. Built in 1957, the museum had the good taste not to erect a statue of the man called “The Father of Nations” and it does refer to the purges, the gulags and the 1939 pact he formed with Adolf Hitler.

“We’re not proud of Stalin,” Lela said.

Ten facts about Stalin

Ten not-so-fun facts you probably didn’t know about Stalin, a man who from 1924-53 ruled one-sixth of the planet:

- Stalin was a nickname. He was born Loseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili. He was given the name “Stalin,” the Russian word for “steel,” at 34 in 1912 during his three-year exile for various offenses.

- His father, Besarion Jughashvili, was a cobbler whose shop in Gori failed. He became an alcoholic and beat his wife and son, the lone child to live past infancy. At age 5, Stalin’s mother took him and left Besarion. They lived in nine different homes over the next decade.

- He showed early skill in the arts. At the Orthodox Gori Church school, he excelled at singing, poetry, painting and drama.

- At 16, he enrolled in seminary school in Tbilisi and published poems that became “Georgian classics.”

- At the seminary, he eventually declared himself an atheist and stormed out of prayer groups.

- At 21 he began work at an observatory and on the side taught socialist theory to a growing number of followers.

- At 27, Georgia’s Bolsheviks elected him to the Bolshevik conference in Saint Petersburg where he clashed with his predecessor, Vladimir Lenin.

- In July 1937, 13 years after he took power, Stalin arrested 268,950 “anti-Soviet elements,” 75,950 of whom were executed.

- During World War II, Stalin ordered all soldiers to fight to the death or be labeled as traitors if captured. The Germans captured his son, Yakov, who died in custody.

- When he died in 1953, the New York Times reported that his own Politburo poisoned him. His embalmed body was placed in Moscow’s House of Unions for three days. So many people viewed his body, many were killed in the crush.

A fun parlor game I sometimes play is debating this question: Who was worse, Lenin or Stalin? I asked Lela.

“Who knows?” she said. “One started and the other finished.”

Uplistsikhe

In about 10 minutes we came through the village of Kvakhreli to the outskirts where we saw a huge limestone hill, strangely carved by nature. We were met by Tamar, another guide who led us up modern steps to a plain.

Before us was a tall sandstone cliff. Carved out of it like two-car garages were caves bigger than my living room in Rome. These housed people for centuries. Writing in Georgia’s beautiful loopy alphabet decorated walls, like early graffiti.

Outside were giant holes used to store grain until the 6th century. Another large surface was used to sacrifice animals. Some of the caves were built during the Middle Ages starting in the 5th century and many were later destroyed when the Mongols overran this territory during the 13th and 14th century. The Mongols used some of them for shelter as raping, pillaging and plundering required a lot of rest.

Walking in and out of the caves, I noticed modern wooden beams holding up some, signs of obvious reconstruction. But these caves are what the inhabitants lived in more than 2,000 years ago. It’s a honeycomb city of limestone.

Some homes were quite elaborate. I saw one with a big opening for a fireplace. One had a long row of double shelves. The archaeologists found 58 jars of wine from the Middle Ages, three wine cellars and seven wine presses. They also found six kilos of gold.

Yes, before communism, before the Mongols, folks in Uplistsikhe lived well.

When Christianity spread in the area in the 4th century, one giant cave was turned into a basilica in the 6th century. A church atop the complex still exists. Built in the 10th century, St. George was destroyed by many earthquakes and rebuilt to its present condition in the 18th century.

Inside it’s small but features beautiful leaf relief paintings and the ubiquitous St. George, Georgia’s patron saint, sticking a spear down a dragon’s throat.

We went to Mtskheta and poured into Kera, a big restaurant on a pleasant lake. We gorged on an endless stream of cucumber salad, breadsticks, cheese plates with honey, fish, the Georgian trademark khachapuri cheese pie, sour rice, potatoes and sausage. The restaurant kitten crawled on my lap trying to seduce me into giving it scraps.

Rural Georgia

As an admitted nerd of communist culture, I found the drive back to Tbilisi riveting. We passed huge farms of apples and pears but the farms were dead, tired, run down. Lela explained that the fall of the Soviet Union took away the Georgian farmers’ safety net. As long as they reached their quotas, the communist state took care of them.

When the Soviet Union fell in 1991, the farmers were on their own. With costs rising in the new democracy, it became cheaper to import produce than produce it. Lela said 90 percent of the families have at least one member living abroad. They all return to the farm on vacation.

The homes looked as if they hadn’t been lived in for years. Bars covered broken windows. Balcony railings rusted over. Fences laid on the ground as if felled by a strong wind and no one bothered to replace them.

As in so many ex-communist countries, the cities are thriving while the countryside is dying. Meanwhile, Uplistsikhe lasted for 70 years. Georgians still drink to that.

If you’re thinking of going …

How to get there: Take a marshrutka minibus from Tbilisi’s Didube bus station to Gori. The 90-minute ride is about €2. A marshrutka from Gori to Kvakhvreli is about 30 cents and takes 20 minutes then it’s a two-kilometer walk to the site. A taxi (prepare for a wait) to Uplistsikhe from Gori is about €10.

Price: About €5, about €16 with guide. 9 a.m.-6 p.m.

Where to stay: Citrus Hotel, 39 April Street, Tbilisi, 995-32-255-9300, https://sites.google.com/view/citrus-hotel/. Great location short walk up hill from the historic Parliament building and a seven-minute walk from bustling Freedom Square. Helpful, English-speaking staff. Big rooms. I paid €280 for four nights, including a good buffet breakfast.

Where to eat: Kera, 3 Sanapiro, Mtskheta, 995-557-37-1970, https://www.facebook.com/KeraRestaurants, 1-11 p.m. Monday-Friday, noon-11 p.m. Saturday-Sunday. Many traditional Georgian dishes specializing in fish. Located on a pretty river 30 miles (57 kilometers) southeast of Uplistsikhe.

Barbarestan, D 132 Davit Aghmashenebeli Ave., Tbilisi, 995-551-121-176, 2-11 p.m. A must stop. All the traditional Georgian dishes made from recipes found in a cookbook from 1914. I was disappointed in my last visit that they removed khachapuri from the menu as it’s viewed as too mainstream. I paid €58 including wine.

When to go: Tbilisis is cold in winter and hot in summer. It has regular lows in low 30s and highs in mid-40s in winter. Summer it gets in the 90s with high humidity. Snow is in the Caucuses year round. In the Mestia area, winters get down to the mid-teens. Ideal hiking weather is summer when highs are mid-60s.

For more information: Tourism Information Centre, 4 Kutaisi, Gori, 995-370-270-776, ticgori@gmail.com, 10 a.m.-6 p.m.

February 27, 2024 @ 11:56 am

Great expose as always John. Definitely on the bucket list.

February 27, 2024 @ 1:34 pm

Thanks, buddy. Stop at the Stalin Museum. It looked great, er, sort of.