100 books: Retirement is a reading paradise, making life in the virus less like a living hell

So how do you like your company now?

I see divorce filings are up all over the United States. Domestic violence is up in Asia. Netflix stock must look like Apple 20 years ago. In this time of international lockdown, people from San Diego to Shanghai are searching in the far corners of the Internet and the closet for something to do. You’ve played Monopoly so often you now refer to your home as Park Place. You found some redeeming entertainment in a documentary on blood clots. And with a little scotch tape, you really can make decent origami out of toilet paper.

I feel sorry for anyone during this coronavirus crisis who doesn’t like to drink or read or can’t afford a Netflix subscription. Wednesday marked my 31st day in lockdown in Italy, the first to place draconian measures on an entire country. Tuesday I saw my girlfriend, Marina, for the first time in 30 days. She lives four miles away.

However, I’m lucky. Besides living alone and being a bit of a loner, I’m also a readaholic. This “mostro invisibile (invisible monster),” as it’s often called in the Italian press, has been a blessing — if I can find the tiniest of optimistic slivers in a virus that has killed more than 17,000 people in my adopted country.

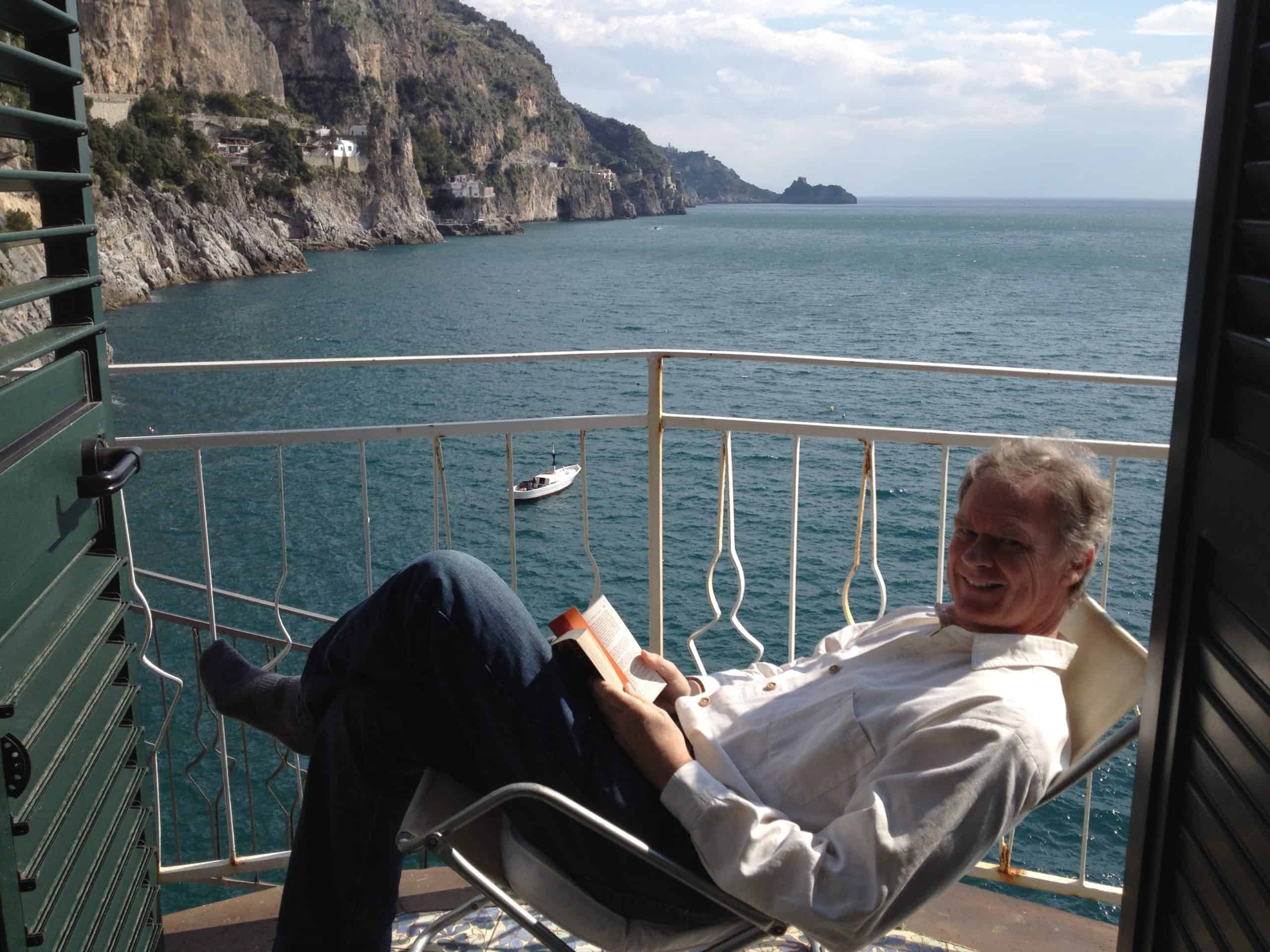

I can read. I can read all day if I like. In fact, that part hasn’t changed much from my last six years in Rome. If any of you find no more simple pleasure than sitting in a chair with a good book and wondering what retirement would be like, picture heaven in a library. I retired to Rome in January 2014.

Last week I read my 100th book in retirement.

I don’t favor a particular genre. I alternate fiction and non-fiction. I read books published as far back as Charles Dickens’ “Pictures from Italy” in 1846 and Robert Ludlum’s 2019 novel “The Guardians,” which, ironically, was book No. 100. I’ve read books in Italian and English, good and bad, funny and sad. I’ve read books about Laos and Iceland and North Korea and Ecuador. I’ve read lots of books about Italy, from the emperors of Ancient Rome to the various interpretations of Italian hand gestures.

My escape during this lockdown is my bookcase. My bottom shelf is lined with books I haven’t read, ranging from a biography of Leonardo Da Vinci to a murder mystery about a British jockey disappearing in Norway. Every time I begin a new book, my apartment is like Christmas Day. I can’t wait to pick it up, unwrap it by opening the cover and dive into a world apart from the one I’m living.

Retirement in Rome is heaven. Today the world is going through hell. I’ve blogged about the virus for five straight weeks. I want to escape. If you do, too, below are my recommendations for the best books I’ve read in the last six years. They’re broken up into alphabetical-ordered genres. They may sound familiar, if any of you follow the mini-reviews I post on Facebook. Regardless of when I read them, the thoughts and feelings are still fresh.

Here’s hoping one or two help you get through long days inside, during good weather and bad, through isolation, fighting children or a nagging spouse.

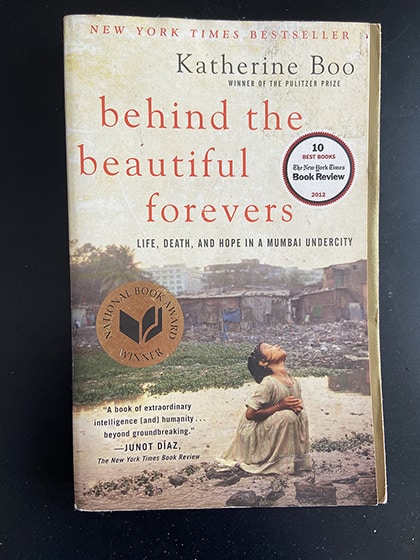

Armchair travel: Behind the Beautiful Forevers, Katherine Boo, 2012.

As a travel writer, this is my favorite genre. The only drawbacks are they make me jealous for the places the writers have been and how well they write. I’ve done some crazy things in travel writing (scuba diving with sharks, a 24-hour Amazon Jungle survival course, eaten ox penis), but Katherine Boo outdid me.

The New Yorker writer spent years off and on in the heart of Mumbai’s teeming ghetto. In the shadow of luxury hotels and the international airport, the slums of Annawadi are a stinking cauldron of desperate humanity. Its kids roam in packs taking discarded plastic home to make household items.

It’s where the houses are so filthy, children wake up with rat bites on their ass. It’s also where the annual monsoons wash away their homes and they must start over again. Boo spent months inside the ghetto, getting to know the characters whose hope is as low as their life expectancy. Theft. Tragedy. Jealousy. Prejudice. It’s all jumbled together in a world few of us ever see.

I laugh at Indiaphiles, those backpackers who love India so much because of its mosaic of cultures, food and, more than anything to be honest, prices. They scoff at Indian states like my beloved Kerala, the cleanest, safest and least poor of them all.

“It’s not really India,” one woman in ugly cornrows told me. But they never go to the real India. They never go to Annawadi. That’s the real India.

Classic: Journey to the Center of the Earth, Jules Verne, 1864

Travel makes you want to read. When I started traveling at 22, I wished I’d paid more attention to my Western Civ classes. So I started reading about the artists whose art I saw in Italy and about wars after I crossed the battlefields in France. Nearly 40 years later, my reading and traveling still come together. Take one adventure from 2017: Iceland.

In my last few days on that two-week trip in May, I toured West Iceland’s Snaefellsnes Peninsula. I remember circumnavigating mighty Snaefellsjokull, the massive 4,475-foot volcano whose snow-rimmed crater dominates the entire landscape. It was this mountain that inspired Jules Verne’s 1864 epic science fiction novel, “Journey to the Center of the Earth.” When I left Iceland, I couldn’t wait to order the book and read what the French author described under the mountain that took my breath away.

It’s about a German mineralist named Liedenbrock who discovers a parchment from Arne Saknussemm, a 16th century Icelandic alchemist who mentions a passage to the center of the earth through Snaefellsjokull. Liedenbrock deliriously follows Saknussemm’s footsteps and prepares a journey to Iceland.

The story is told through the words of Axel, Liedenbrock’s skeptical but loyal nephew who figures the crater will be a dead end and they’ll both return safe and sound. Not true. They find an opening. What ensues is a two-month journey that became arguably the best science fiction book I ever read.

They have no map. They face dinosaurs. Their lone lights are sketchy lamps. Claustrophobes should NOT read this. I’m not terribly claustrophobic but I visibly shuddered when Axel gets separated from Liedenbrock and their quiet Icelandic guide and his light goes out. Lost. In the dark. Under 200 miles of solid rock above him.

Yet what happens to the trio is a testament to man’s courage, curiosity, adventure and discovery. Kind of like traveling.

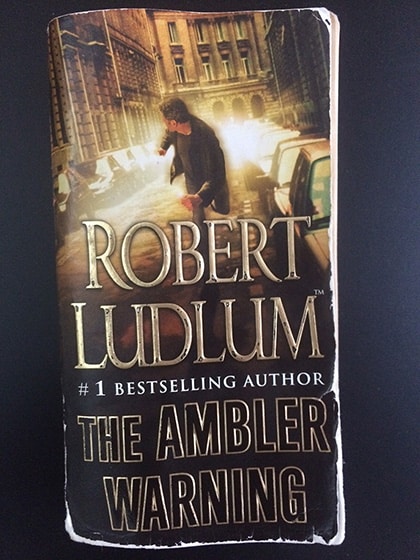

Fiction: The Ambler Warning, Robert Ludlum, 2005

My idea of paradise? A good beach, a good book and a good woman. I had all three one week on the Greek isle of Skiathos where Marina and I returned after three years away. Our four-star Esperides Hotel had a gorgeous beach with lounge chairs, perfect for a page-turning novel.

I brought one of the best page turners of them all: Robert Ludlum. He cranked out spy mysteries from the 1970s through the ’90s, including the hyped “Bourne Identity” series.

I brought “The Ambler Warning,” published in 2005 curiously four years after his death. A writer and editor chosen by his estate put the novel together. Still, it had Ludlum’s fingerprints all over it. It’s the story of Hal Ambler. At least, that’s what he thinks his name is. He’s a government operative (read: spy) who finds himself in a government mental hospital. Turns out, he knows too much and the government is trying to “deprogram” him.

With the help of a beautiful nurse, he escapes and realizes he doesn’t recognize the face in the mirror, nor does he know anything about his past. The rest of the 632-page novel has him gathering information about his past while preventing others from killing him for a reason he doesn’t know. The nurse catches up to him, adding a carrot to the end of his stick, pardon the expression, if he ever survives.

China becoming the world’s new 21st century power plays a heavy role as do the sneaky, filthy doings deep inside the U.S. government.

Ludlum — or his ghost writers — go so heavy into detail it bogs down chapters and Ambler’s ability to disable groups of attackers gets old. But the ending … my, my … the ending was the best of any Ludlum novel I read. It’s WAY out there.

Maybe I liked it because I sniffed it out early but I never sniffed out the “Why?” Until the end. American literature misses Robert Ludlum.

Historical Italy (Art Division): Caravaggio: A Life Sacred and Profane, Andrew Graham-Dixon, 2010.

I only had two heroes as a kid in the 1960s: Wilt Chamberlain and Bill Cosby, both flawed but brilliant men.

So it’s probably no surprise that I followed that trend to Rome where I found another flawed hero scattered around various churches and museums: Michelangelo Merisi, aka Caravaggio. He was Italy’s greatest painter from the Baroque period and arguably its greatest in history.

It’s why I loved “Caravaggio: A Life Sacred and Profane,” an exhaustive 414-page tome it took me three months to read. Written by British art historian Andrew Graham-Dixon in 2010, it took me through Caravaggio’s life from his tragic beginnings in plague-stricken Lombardy as a child to his tragic death, alone and sick in Porto Allegre, the Tuscan town I’ve visited twice on personal pilgrimages.

Graham-Dixon mixes his life story with in-depth descriptions of every Caravaggio painting, describing each character pictured and the story behind each piece.

Graham-Dixon confirms everything I love about Caravaggio. He was a rebel, someone who showed religious figures as normal people. He took the veil off Mary, the halo off Jesus. The powerful and ruthless Catholic Church at the turn of the 17th century shunned much of his work but couldn’t deny his brilliance.

He collected rich commissions despite the violent, almost sacrilege, nature of his work. He used real prostitutes as models for Mary Magdalene. Unlike every other artist in his time, he never drew sketches first. He just painted free hand, using light, shadow and context better than anyone before him or since.

He was also a carouser and brawler, and the murder he committed not far from where I once lived sent him on a rollicking run from the authorities that took him to Naples, Sicily, Malta and back again. Along the way, he kept himself afloat by selling paintings as his growing fame outweighed his tragic deed.

In the end, his past caught up with him. Graham-Dixon goes into detail about his death, how he got jumped and disfigured on one port landing. His painting and his life never recovered. His later paintings looked like the work of an amateur and he died alone, possibly from heat exhaustion or heart attack. The exact cause remains a mystery to this day.

He was 38 years old.

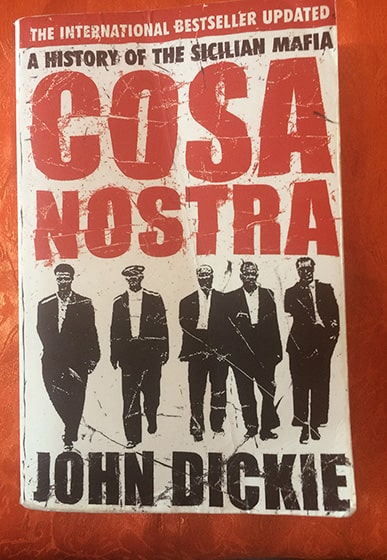

Historical Italy (Modern Division): Cosa Nostra: A History of the Sicilian Mafia, John Dickie, 2004

Being retired in Rome is paradise but the city does have its problems. Litter. Lousy public services. Third world finances.

The biggest one is corruption. It even has a name. Called “Mafia Capitale,” organized crime syndicates have misappropriated funds targeted for public services. It’s one reason the highways on the outskirts of Rome are filthier than most I saw in India.

I get asked a lot about the mafia in Italy. They aren’t as visible as they once were. In fact, their hands are hidden deep in the pockets of politicians. They always have been — when they weren’t holding a gun or the neck of an informant.

I learned how the corruption of today has roots dating to the 1860s in John Dickie’s exhaustive 2004 book, “Costa Nostra: A History of the Sicilian Mafia.”

The mafia actually began in Sicily’s cattle and citrus fruit industries during a time when Sicily was a land of rural outlaws. To this day, the outskirts of Palermo are sprinkled with orange and lemon trees.

Dickie traces the mafia’s path into politics in the 1880s to its role in fascism and communism in the early 20th century to its move to the U.S. to its jump into the heroin trade in the 1950s to the two mafia wars and to the bomb that changed everything in 1992. That’s when the car carrying Giovanni Falcone, an anti-mafia investigative magistrate, blew up near the small town of Capaci.

Since then, the public assassinations have been fewer but the mafia’s hands are still out for its public to scratch.

After the 2006 Winter Olympics in Turin, I took a week off and flew to Palermo. I wrote a food column about Sicilian cuisine (http://www.denverpost.com/…/a-calmer-sicily-sits-down-to-e…/) and went to Mercato Ballaro, Palermo’s sprawling public food market. I asked a meat vendor if the mafia still demands pizzo, the Sicilian name for protection money.

His answer was the most revealing “No comment” of my career.

Humor: Bloodsucking Fiends: A Love Story, Christopher Moore, 1995.

Nothing is harder than writing comedy. Don’t believe me? Go to a comedy club’s open-mike night. The difference between professional comics and wannabes is like the difference between, well, Caravaggio and Sherwin-Williams.

Making people laugh is the hardest genre, particularly without the facial expressions, voice and body motions of a comic. Christopher Moore is my favorite (live) humor writer, now that Hunter Thompson is dead. He takes impossibly ridiculous, childlike plots and turns them into the theater of the absurd.

His satire is out there but his raw writing ability is so strong you laugh at passages you’d think are stupid if told by your neighbor. Take “Bloodsucking Fiends: A Love Story.”

Jody is a smoking-hot, single redhead in San Francisco who gets bit by a vampire and turns into one. During her nocturnal rages she meets C. Thomas Flood, a small-town Indiana boy who works in a Safeway to support himself as a struggling writer.

When Thomas is not turkey bowling in the Safeway aisle with his pack of fellow stockers he calls “The Animals,” Jody recruits him to perform her many daily tasks. While they slowly fall into a very weird love affair (picture foreplay with a vampire), San Francisco finds itself plagued by a series of grisly murders.

The couple think it’s the work of the vampire who bit her. They go to the streets to fight the crime with the enlistment of The Animals and a semi-psycho street person they call The Emperor. This is the first of a trilogy with the next two entitled “You Suck” and “Bite Me.” See? You’re smiling already.

Science Fiction: Earth Abides, George Stewart, 1949

If books are an escape, science fiction is escaping to a higher level. It uses science to project us into a life that you never considered possible but, if you think about it, could actually happen. Even “The Time Machine” is more believable than religion.

Not all the fantasies are pleasant, however. Take a plague that wipes out the world. Imagine yourself in a post-apocalyptic United States. It’s not so tough now. Just walk outside. That’s what George Stewart’s 1949 epic, “Earth Abides” explores.

It’s about a young man named Ish who wakes up one morning to realize he is about the only person alive in the Bay Area. The rest of the book is about his life of survival and what Mother Nature does when there’s no man to control her. An ant plague. A rat plague. You get the idea.

The book is basically in two parts: His exploration of America where he finds a car and drives with no need for money. Think about it. There is no police. No one is manning supermarkets or gas stations. He is a little kid exploring a destroyed playground that is America.

The second part is meeting an older woman who becomes his wife. They resettle back in the Bay Area where a few survivors form a tribe. The rest of the book describes the life of a very small community in a world with no structure.

What is the life like? In a word … boring. But the book is not. The interactions of the community come across as a combination Swiss Family Robinson and Little House on the Prairie. It’s not just life in small town America.

It’s life in no town America. Ish becomes the de facto leader of this tribe and tries grooming an undersized but intelligent offspring to replace him. Then it becomes the relationships between the old, those alive before The Great Disaster, and the new, the children who know no other world but this vanquished landscape.

Personally, I would rather die in the plague — or coronavirus.

Sports: Boys in the Boat, Daniel James Brown, 2012

I don’t often read sports books. I was a sportswriter for 40 years. I read sports for a living. But I read a book I received as a Christmas gift and I absolutely adored “The Boys in the Boat” by Daniel James Brown. This isn’t “The Roger Staubach Story.”

It’s about the United States’ Olympic gold-medal 8-man crew from the 1936 Olympics. A bunch of small-town blue-collar kids from the state of Washington spent three years together at the University of Washington then went to Berlin and beat the Germans in front of Adolf Hitler.

It focuses on Joe Rantz, who bounced around the state of Washington as a kid before settling in the tiny northern peninsula town of Sequim where his father and stepmom abandoned him. It’s a great story of overcoming family crap, the Depression and the rest of the world just before the U.S. entered World War II.

The details Brown put in the book made me think I was right in the boat with them. There are more details in the book, “How Seattle Became a Big-League Town: From George Wilson to Russell Wilson,” by my old partner in crime in Seattle, Dan Raley.

World History: In Order to Live, Yeonmi Park, 2015

I’ve always been fascinated with places no one else has been. I went to Albania in 1994 the year after its communist government fell. I went hiking in Borneo’s Kelabit Highlands, called one of the most remote places on earth.

This is why North Korea was always on my bucket list. I watched every video and documentary I could find on it. However, nothing I’ve seen places such an illuminating and frightening magnifying glass on this isolated culture as Yeonmi Park’s “In Order to Live.”

Park was a North Korean 13-year-old girl who didn’t live in the capital of Pyongyang, the site of the documentaries I saw. She lived in Hyasen, a small, starving town on the Yalu River bordering China.

Her story of survival in her own country, escape to China which wasn’t much better and final sanctuary in South Korea, also a major adjustment, isn’t just a testament to the human spirit. There are many of those.

“In Order to Live” is arguably the most brutally honest account of life in North Korea ever written. She wrote of surviving on nothing but leaves and bugs she and her sister gathered in the surrounding forest. “Most girls my age caught dragonflies,” she wrote. “I ate them.”

A drought caused crops to fail and for fertizilzer the government told its citizens to use human dung, forcing rural North Koreans to collect their own and even steal from others.

North Korea, she wrote, actually was livable until 1990 when the Soviet Union collapsed and North Korea lost its trade partner. Instead of forming trade partnerships with other nations, North Korea told its 25 million people to get behind their Dear Leader and survive. Also, ahem, only eat once a day.

Fearful of starving to death, she and her mother escaped to China where they fell victim to human trafficking by the ruthless Chinese agents praying on desperate refugees. One agent raped her mother in front of her.

They managed to escape to Mongolia and eventually reach South Korea where Park has emerged as the face of the North Korean tragedy.

The book was riveting. My compliments to the translator. If she wrote this in English, she’s more brilliant than Kim Jong-un gives her credit as he and his thugs denounce her on North Korean media.

I’d still like to visit North Korea. But after this posting admiring Yeonmi Park so much, I doubt they’ll ever let me out.

April 8, 2020 @ 10:00 am

Very nice, John! I’ll share this. Stay safe!

April 8, 2020 @ 10:12 am

I am just about to re-read “Behind the Beautiful Forevers” because I own it and it made such an impression on me the first time. After quarantine the Caravaggio will be next. This is a really good list.

April 8, 2020 @ 10:33 am

OK, I’m gonna have to read Earth Abides again.

Great list!

April 11, 2020 @ 4:41 am

Thank you John for all those wonderful recommendations. I look forward to looking at several after your very informative descriptions.

Keep safe and well in your beloved adoptive country.. my heart goes out to all.

April 14, 2020 @ 3:01 pm

Thanks for the book reviews. You made me hungry thinking of the food in Sicily!

Be safe.