Sahara Desert: Camping in endless sand brings out the beauty and beast of Earth’s intimidating landscape

(Director’s note: This is the second of a series of blogs on Algeria.)

SAHARA DESERT, Algeria – Nothingness.

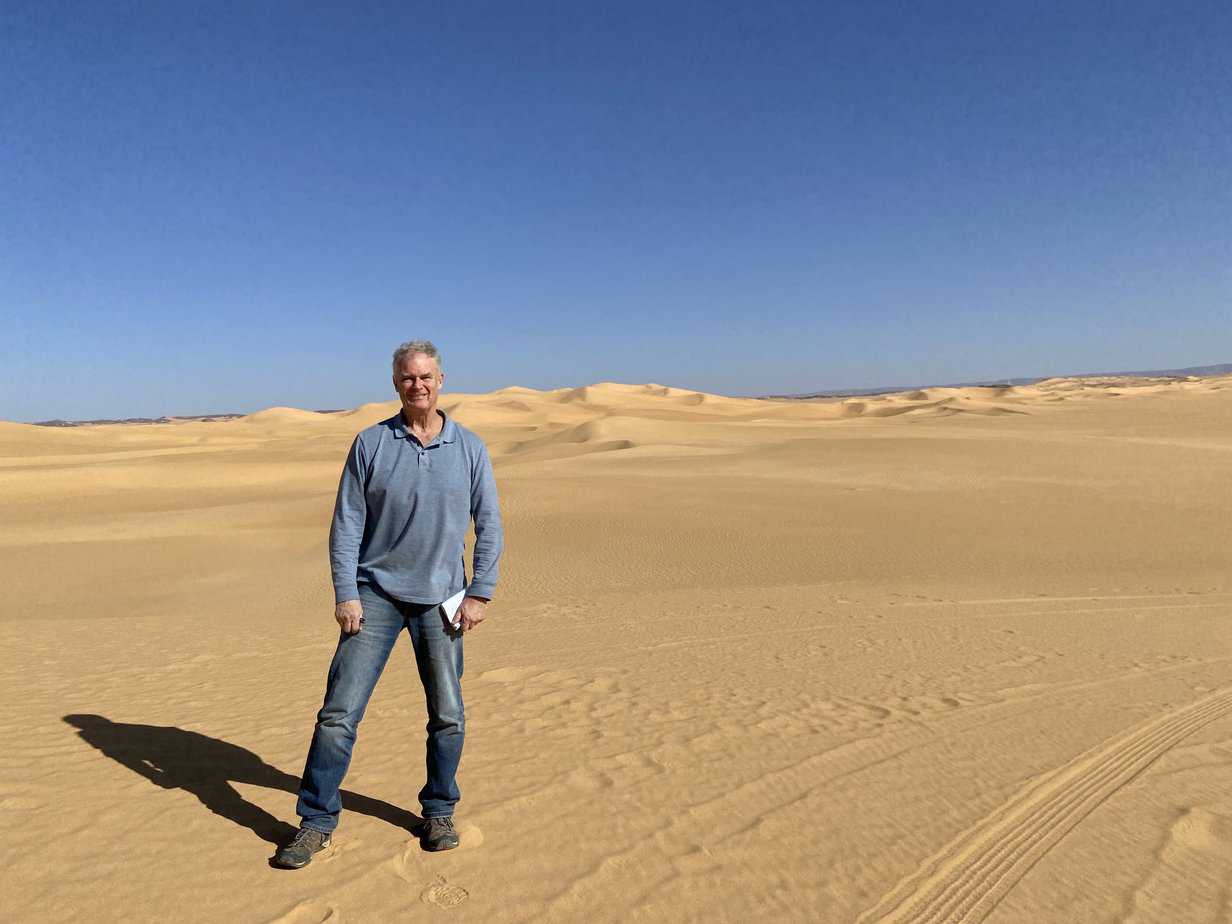

Nothingness to the north. Nothingness to the south. Nothingingness to the east. Nothingness to the west. I stood in a sand bowl that could hold a small city. Everywhere I looked I could see nothing. Except for a tiny line of distant mountains thousands of miles away, I saw sand. That’s it. After a day deep in Algeria’s Sahara Desert, sand felt like nothingness.

It’s truly intimidating the Sahara. I was 40 miles (70 kilometers) from the nearest town. Left alone here, I would not survive any better than if you dumped me in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea. The Sahara is 3.6 million square miles (9.2 million square kilometers). That’s almost the size of China.

Algeria, the 10th largest country in the world, is 90 percent desert. The Sahara covers about 735,000 square miles (1.9 million square kilometers) of it. That’s a couple of Augusta National sand traps smaller than Mexico.

Sahara’s numbers

If the Sahara was a body, I’d be standing close to the belly button. I was near Algeria’s southeast corner, 920 miles (1,485 kilometers) south of the coastal capital of Algiers. I was 50 miles (80 kilometers) from the Libyan border where the Sahara continues covering the driest swath on earth all the way through Egypt.

According to the International Organization of Migration, 5,600 people have died trying to cross the Sahara since 2014. That includes approximately 150 last year.

I don’t believe it. The number must be more. If I died of thirst, starvation, dehydration or heat stroke out here, no one would find me until my bones were dust mixed in with the desert sands. If only these sands could talk.

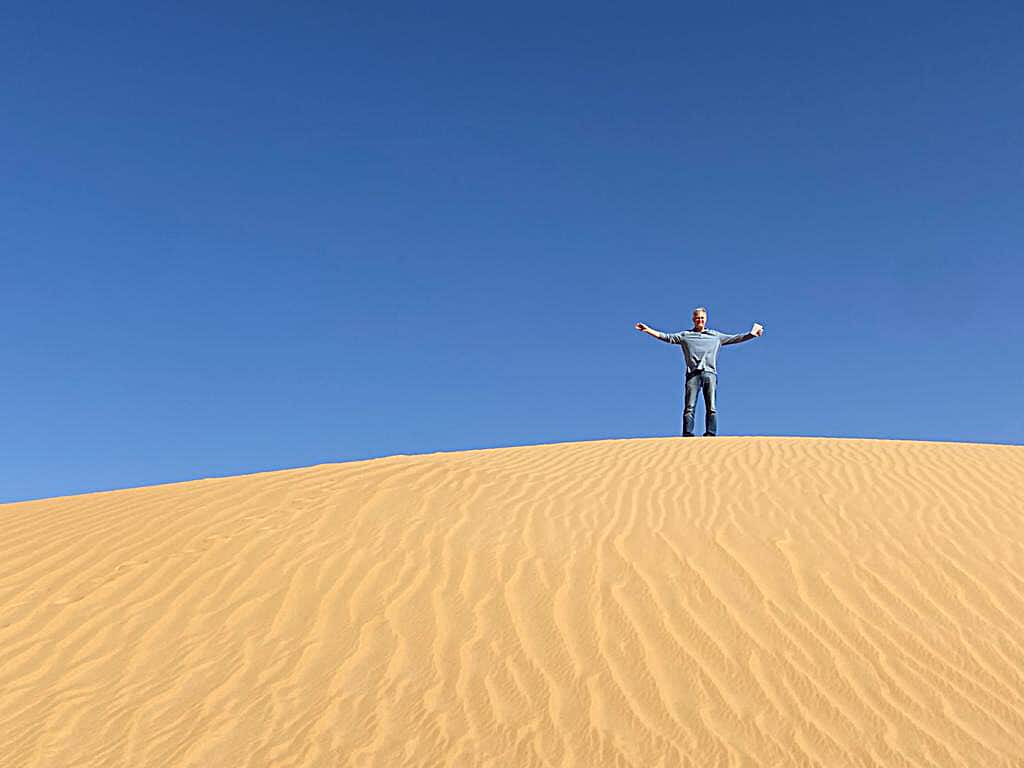

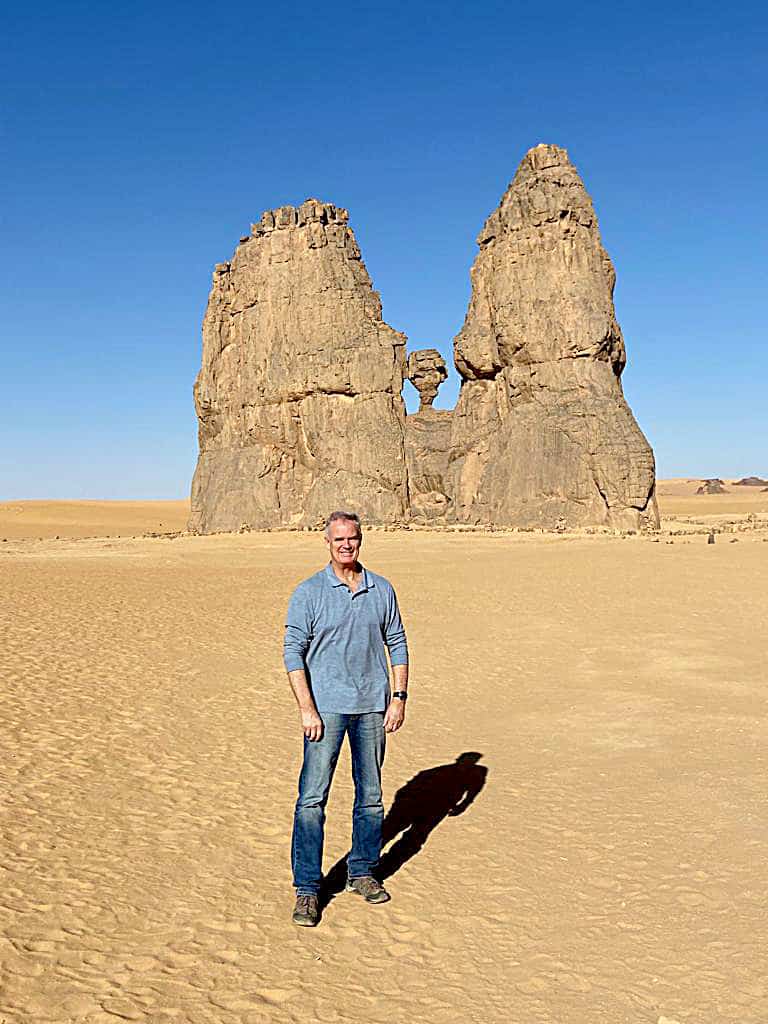

But just like the deadly oceans, the Sahara matches its intimidation with raw beauty. Sand dunes, wind whipped for centuries, have the contours of gold meringue. Sand stretching to the horizon has a symmetry about it, like earth’s original canvas. Black cliffs, carved by a long-gone river that flowed through here millions of years ago, stand at attention like sentries.

And rock carvings that are 8,000 years old but clear enough as if drawn last week, hammer you with the knowledge that people once actually lived here.

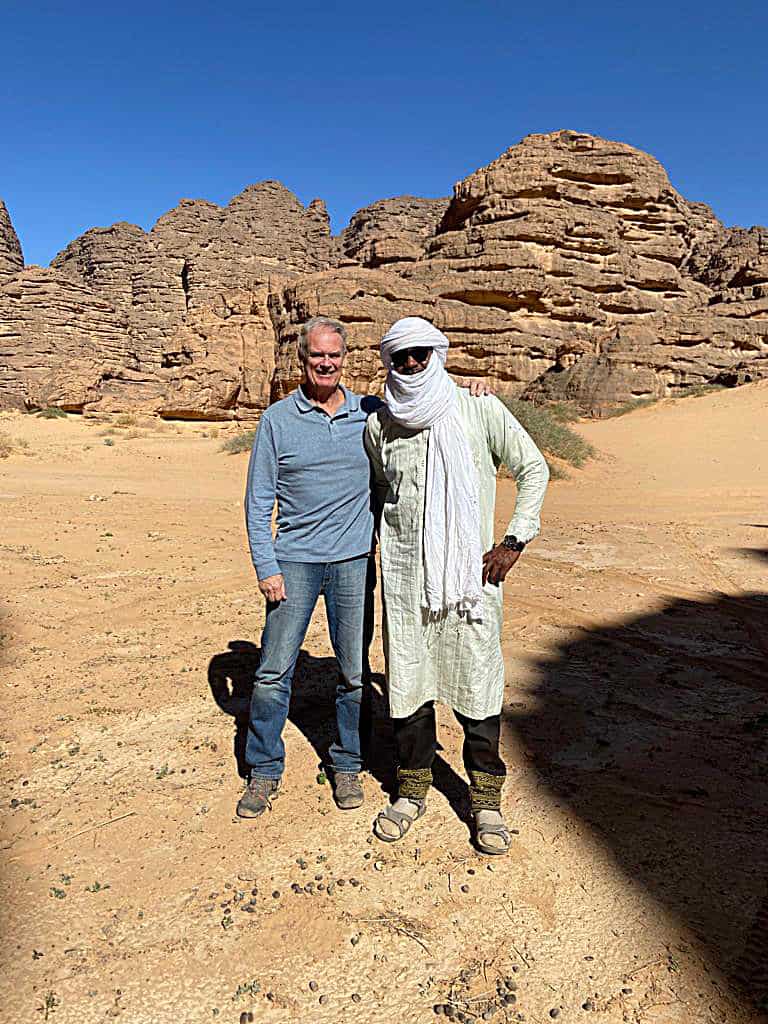

Few places on earth can make you feel more alone than the Sahara. Fortunately, I was with a trusted guide named Ibrahim and my fellow travelers from the Travelers’ Century Club (TCC). Earlier this month I spent nine days crisscrossing Algeria with TCC, reserved for travelers who’ve been to at least 100 countries and territories.

We are all hardened adventurers. This group has done everything from snorkeling with man-eating sharks to traveling in North Korea. This was my third trip into the Sahara.

But I had never gone this deep into it or covered 100 miles (170 kilometers) of it. In Egypt in 1978, I rode a camel for 30 miles round trip from the Great Pyramids to Saqqara, the world’s oldest pyramid – and subsequently could not sit down for a week. In Tunisia in 2002 I rode a camel for three days and two nights inside the northern lip of the Sahara just south of Douz. While I wasn’t in the middle of nowhere, I felt like it on the first day when I saw the rotting carcass of a dead donkey.

Getting there

Where we were going in Algeria, camels would take weeks. We flew. This gave us our introduction to the timetable from hell that is Air Algerie. Our flight was scheduled to leave at 11 p.m. and we would land in the town of Djanet at 1:15 a.m.

This would be the first of three flights we took between 10:35 p.m-1 a.m. Air Algerie is by definition a fly-by-night airline. The airline has a shortage of planes. Most of them are used for more popular routes during the day. The less-traveled routes are given the night skies. That includes Algiers-Djanet, a desert oasis of 17,000 people who receive about half an inch of rain per year.

Also, Air Algerie has a nasty habit of changing time schedules. Two weeks before my trip, they threw in a stopover in Houari Boumediene, in eastern Algeria and whose namesake, Algeria’s president from 1976-78, certainly would’ve been just as perturbed as we were not arriving in Djanet until 3 a.m.

But TCC is low-maintenance. No one complained. I didn’t. Camping in the Sahara does not call for Lear jets and four-poster beds.

The plane was filled with Algerians heading home, all wearing the desert uniform: full-length brown robes with elaborate head scarves wrapped a dozen times. Piercing eyes stared out of faces as black as coal. I felt like I was on the set of Dune.

Djanet’s baggage claim area buzzed with excited tour groups and their guides. We met Ibrahim, standing about 6-foot-4 with a yellow headdress. He spoke fluent English, learned through school, movies, music and years of intrepid travelers.

“Welcome to Algeria!” he said.

He broke us up into various vans for separate destinations. Some TCC members chose a hotel in Djanet over a tent in the desert. While the others were tucked into their comfy beds, we were flying like bats through the pitch black night. Not a single light illuminated our path. The overcast sky didn’t even have a star. We were driving into a void, a wrinkle in the atmosphere into another world.

Ibrahim, fortunately, didn’t hear my cynical question about 300-meter worms.

After an hour, we came to a clearing between some of the few shrubs we saw. Some small, two-man tents waited for us. It was 4 a.m.

I crawled into the tent’s sleeping bag. I heard someone ask about scorpions. I don’t think anything could survive out here. I told myself that as the feet on my 6-foot-3 frame stuck out of the little tent.

I finally fell asleep at 5.

Sahara tour

The desert is best seen in the morning. The heat of the day is a long way off and it’s relatively cool when you wake up. What’s surprising is the Sahara’s blinding light. We woke at 8 a.m. Despite only three hours sleep, the sun bouncing off the gold sand like a meteor shower jolted me into full alertness.

People don’t know how cold the desert can get. It gets into the 40s at night and we woke to 52 degrees (11 celsius). I asked Ibrahim what’s the hottest he experienced here. He said he felt 45 (113 Fahrenheit). In 2018 it hit 51 (124) in Ouargla Province between here and Algiers.

“But it’s dry,” said Jose, a Spaniard. “Not like in Madrid.”

Tell that to my scorched hands. I lived in Las Vegas for 10 years. When it hit 115 every summer, I had to wear gloves just to handle a steering wheel. Dry heat is as dangerous as an open oven. But this was December. We spent most of the day in perfect sunny 70-degree conditions with it warming by early afternoon. I didn’t even drink much water.

The mild weather turned the desert from a deathscape to a playground. I piled into one of three Land Cruisers and we charged across the sand. Our first stop was a 50-foot rock wall. On the bottom of the wall were rock carvings dating back to 8,000 B.C. An accompanying archaeological guide pointed to the outlines that, if you connect the dots, clearly depict five cows, complete with horns.

There isn’t much vegetation in the Sahara, obviously. What is there can kill you or cure you. Ibrahim pointed out a leafy green plant that wouldn’t look out of place in a spinach salad. Called a calotropis, if you get it in your eyes, you will go blind in nine minutes. Not eight. Not 10.

Nine. Yes, I guess they have seen it happen.

Later we stopped at a bush full of ugly, prickly branches with small green leaves. This l’armoise plant bears medicine that is so good for the stomach, the Algerian medical community used it on Covid patients. Ibrahim told us to take a deep breath over it. It smelled like Vicks Vaporub and I could feel it all the way into my lungs.

Mostly, we enjoyed just driving around on the endless expanse of sand. We were the only three vehicles we saw all day, and we’d stop at various points of interest where we climbed around towering sand dunes like kids at the beach.

No souvenir shops. No tour buses. No … people. The only camels we saw weren’t for photo ops. They were eight wild camels making their daily rounds.

You can’t visit Algeria’s desert without a permit, a guide and police escort. A guide is essential. Who else could find the little pieces of ancient pottery and cutting tools that can still be found in the desert? Or explain that the half buried car tires we stumbled upon mark pieces of land that Algerians actually purchased?

Nearby Ibrahim got out to pray. One of the drivers drew a line in the sand. What was this? It was the Tropic of Cancer. That spot is the most northerly circle of latitude where the sun can be directly overhead.

I’ve been on the Equator in Ecuador which built an entire visitor’s center and elaborate marking for photo ops. Yes, I have a photo of me with feet in both hemispheres.

Algeria’s Tropic of Cancer is marked by deflated, half-buried car tires.

The Sahara here has not always been desolate and empty. For centuries, camel caravans ridden by Berber tribes have come across these sands. Lately, however, Libya’s government has demanded more documents at its Algerian border, discouraging movement.

Also, Ibrahim said in the 1970s the Libyan government built a small village near the border. The village didn’t last long. They all left.

“This is a desert,” Ibrahim said.

Lunch

The Sahara isn’t completely flat. At about midday our cars came across a series of towering black cliffs, called the Tikabawin Rocky area, ranging from 30-100 feet high. Millions of years ago, a river covered this area and formed the cliffs that still remain. We sped between them like they were skyscrapers in a cityscape.

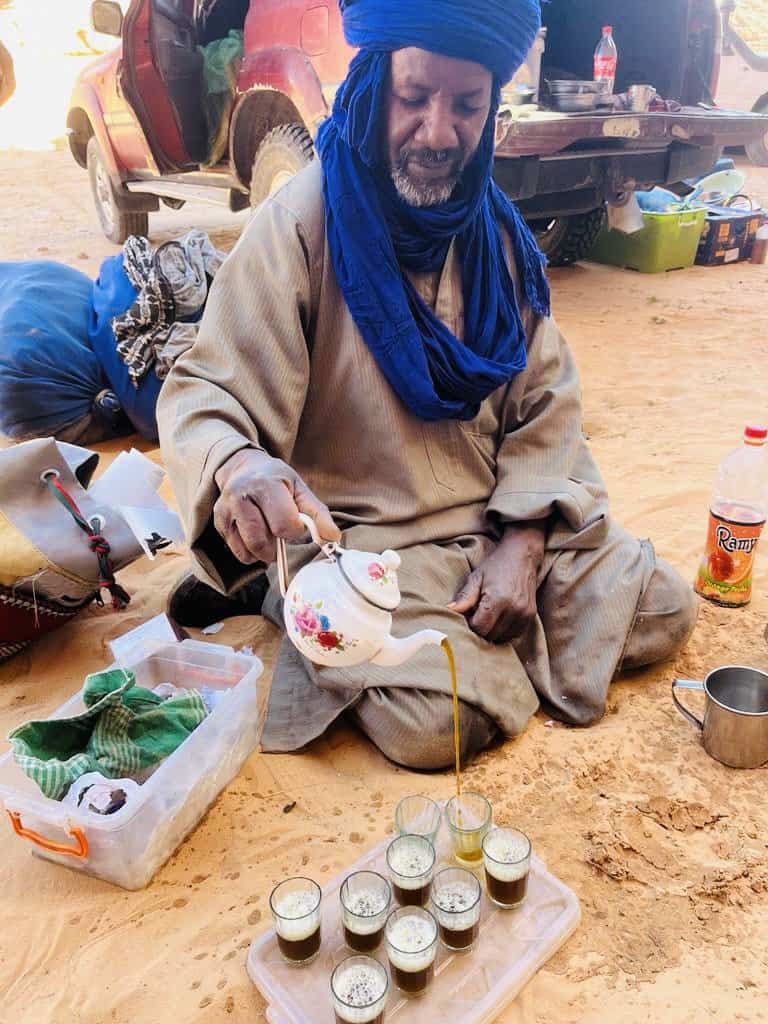

They provided nice shade for a lunch break. Ibrahim and his crew laid out quite a spread: Lamb balls with tomatoes, peas and bay leaves, salad, bread and tangerines, still chilled from the night air.

Afterward, Vasilis, the solitary Greek, stood up and turned to Ibrahim.

“We have some time?” he said. “I go for a walk.”

“The desert is like a maze,” Ibrahim said. “Don’t go far.”

“You don’t trust me?”

“I don’t trust the desert.”

I wandered around, getting a closer look at this global mass. I saw a cactus-like plant that looked quasi dangerous. I noticed a bird’s footprints on the sand. I had yet to see a bird anywhere. I noticed the cliffs had natural hand holds. I wondered if rock climbers would be a rich market for Algerian tourism if it cared.

We piled back in the vans and veered in and out of the cliffs before they faded in the rear view mirror and we saw nothing but sand. Sand everywhere. It was a gold canvas all the way to the horizon everywhere we looked.

By about 3:30, the three hours of sleep over two days and the heat that rose to 75 degrees (24 celsius) started to hit me. I began to fade. I was jarred awake with a stop at an arch where we saw rock drawings of dancers. Ibrahim dated it to 4,000 B.C.

We headed back at about 4:30 p.m. The sun started to burn the distant sands into a light red. After a 45-minute drive, I thought I saw a mirage. The vision jiggled as the Land Cruiser bounced along the sand. It wasn’t a mirage.

It was a road. Looking newly paved with jet-black asphalt, the lone road in the vast desert looked like a pencil line on a gym floor. We got on the road and saw a sign in Arabic and Roman letters.

“Djanet.”

We all went to a guesthouse for a big meal of vegetable stew and tea. Then before our 12:45 a.m. flight back to Algiers, in a big room lined with cushions and elaborately decorated rugs. we all crashed for a couple hours.

Nothingness.

(Next: Ghardaia, Algeria’s most traditional city.)

If you’re thinking of going …

How to get there: Air Algerie has one direct flight to Djanet at 10:30 p.m. The 2-hour, 15-minute round-trip flight is $185.

How to get around: The Algerian government requires permits, guides and a police escort to tour the Sahara. It is best to organize a tour. TCC used Algeria Tours 16, https://www.facebook.com/Algeriatours16/?_rdc=1&_rdr, algeria.tours16@gmail.com, 213-773-62-0805. Owner Wassim Allache, is well traveled and is fluent in six languages. He handled everything for us with nary a wrinkle. The overnight trip was part of a nine-day Algerian tour.

When to go: October-April. Highs range from 67 in January to 77 in April with a low of 53 in January. From June-August highs average over 100 and often hitting 115.

For more information: Tourism Algeria, https://www.tourismalgeria.com/index.html, info@tourismalgeria.com.

December 19, 2023 @ 1:50 pm

Impressive indeed. Great article John.

December 19, 2023 @ 3:39 pm

This is one leg of your trip I’m pleased to be living vicariously, with no thought of retracing your steps.

Still: Thanks for taking us there. Too, too cool.

December 19, 2023 @ 4:41 pm

Thanks, Neal. So it didn’t remind you of Vegas?

December 20, 2023 @ 4:31 am

Excellent article. My secretary in Rome has been to Algeria or Chad or somewhere with a lot of sand. Her photo of their campsite, taken from a high dune, made the entire desert look like a golden ocean complete with swells. Most impressive. Putting this on my list.

December 20, 2023 @ 10:47 am

Thanks, Jeff. I do love the desert but bring a car. A camel is slow going. And after too many days in the desert, that camel starts looking pretty good. Where’s your next adventure? We go to Azerbaijan for five days end of January then to Tbilisi for a travel bloggers conference. Then we must schedule Kyoto over my birthday in March, Cyprus over Marina’s birthday in June and Oregon and California for a high school reunion and nephew’s wedding on the same CAZZO day. We’re just going to the reunion’s meet and greet in a tavern that Friday the 19th then fly down to San Luis Obispo for the wedding the next morning. Wanted to stop over in Colorado to or from but it’s a bit complicated. This morning, Marina is dreading another Christmas at her parents. So we decided: 2024 in Budapest. We’re going soak in spas.

December 20, 2023 @ 6:30 am

What an invigorating read, thank you so much for sharing.

December 20, 2023 @ 10:43 am

Thanks, Arabella. Ever been to North Africa? It’s actually quite safe for women.

December 20, 2023 @ 1:58 pm

This comes article comes right on schedule for us. I’ve always wanted to visit North Africa. My husband and I are planning a trip to Morocco but we just might change to, or add, Algeria! We both love deserts. Ever since we visited a national park of drifting dunes (a mini desert) in Paraguana, the northern peninsula of Venezuela, many years ago, we fell in love with that landscape. Five years ago we traveled to Patagonia and visited its desert, and most recently he went to Death Valley. We don’t exactly have a bucket list for deserts (I still love forests) but the ocean of sand and vast nothingness puts our existence in perspective. Thanks again for another great read.

Tanti Auguri e Buon Natale!

December 20, 2023 @ 10:16 pm

Thanks, Cristina. I highly recommend Algeria Tours 16. Don’t try to organize this on your own or even get a visa on your own. As I wrote in my first blog, a Canadian tried for two or three years and just said, “Screw it!” and joined a tour. Wassim who runs Algeria Tours 16 is really good at getting everything organized.

John Henderson

December 27, 2023 @ 6:22 pm

Thank-you, I really enjoyed this article. It brought up a lot of memories. I had the pleasure to stay in Egypt for a month in the 80’s. The desert, as the sun was setting was one of the most amazing sights I’ve ever seen. Next, I would love to go to Morocco but have some trepidation as going with another female. I would like to start in Marrakesh I believe.

December 28, 2023 @ 7:17 am

Thanks, Venus. I’ve been to Morocco twice but never in the desert. You can’t miss the Atlas Mountains. Try to combine the two. And yes, be careful of the men there, especially in Tangier.

January 10, 2024 @ 7:01 pm

Might want to check your superlative statement in your 1st paragraph…..

In the real atmosphere, other factors limit the visibility of distant objects. From a tall building on a clear day, you can see mountains as far away as about 100 miles.Mar 25, 1996

How Far Can You See? – PUMAS – NASA

January 16, 2024 @ 5:55 am

OK, I admit, it was a hard estimate. Let’s just say I could see a long way.