Kyoto good and bad: From tourist traps to a quiet garden and a room with a view

(This is the fourth of a series of blogs on Japan and Shanghai.)

KYOTO, Japan – The vermilion torii stretched in a graceful arc up the mountain slope as far as I could see. Torii are those beautiful Japanese arches with two vertical pillars connected by a black beam, slightly curved at the ends. They serve as gates to Buddhist temples and one of the international symbols of Japanese architecture.

At the Fushimi Inari-Taisha shrine, 10,000 torii snake below, above and around five huge temples. On the first sunny day of our recent week-long trip to Japan, walking through the torii could’ve been our highlight. It would be very tranquil to walk around a mountain slope under such a beautiful symbol of Japan recognized the world over ….

… if it wasn’t for about 10,000 others who had packed the narrow pathway like it’s 5 p.m. in Tokyo.

Kyoto is arguably the most beautiful city in Japan. It is its symbol of history, culture, religion and architectural splendor. It is home to 2,000 temples and shrines and 17 UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Kyoto is a must see, a site that’s atop even the most hardened backpacker’s checklist.

But Kyoto also has some horrid tourist traps that are as off putting as any I’ve ever experienced. Then again, this is Kyoto. For every temple overrun by selfie-clicking tourists there is a quiet sanctuary nearby where you can sit in a garden and look at green forests, birds chirping in the crisp air and koi swimming in lily covered ponds.

I know tourist traps. I live in Rome. I still shake my head at the long lines waiting to put their arm in the Bocca della Verita, this giant marble disc where if you put your arm through it and tell a lie it’ll be allegedly cut off.

Some places are touristy for a reason. Rome’s Colosseum is an architectural marvel. It’s why tourists visit.

But when the amount of tourists destroys the atmosphere that a site intended to create, it qualifies as a tourist trap. Kyoto has two vivid examples. While we suffered through crowds that would turn a claustrophobe screaming into the wind, we also found escapes that made us sigh and smile, experiencing the authentic Japan that we came to see.

Here was our two-day journey into the worst and best Kyoto has to offer:

Kyoto’s Fushimi Inari-Taisha

I knew we were in trouble mid-morning when the local train out of Kyoto Station was as packed as a third world bus. Asians, Westerners and half a dozen languages filled the train car that disgorged us in a forested area on the southern outskirts of the city.

Lonely Planet listed Fushimi first among all sites, calling it “quite simply, one of the most impressive and memorable sights in Kyoto.”

Religiously, it is impressive. Built in the 8th century, the Hata family clan, the most prominent residents of Kyoto, dedicated it to the gods of rice and sake. Today it is the head shrine for 40,000 Inari shrines scattered around Japan. The Inari are popular deities associated with a variety of Japanese life, ranging from household wellbeing to rice.

The problem is a lot of Japanese follow the Inari god. According to Nippon,com, the shrine attracts 2.7 million tourists a year.

We walked up a short hill to the first torii, a huge gate standing at least 20 feet high with the first temple just beyond another staircase. Filing through were not Buddhist pilgrims but travelers snapping selfies so fast they drowned out the birds singing overhead. Blonde Scandiunavians with backpacks. Japanese tourists with masks. Parents dragging children.

Past the first temple we entered the tunnel of torii. This stretches for four kilometers up the mountain. The torii are built so close together, the sun barely sneaks through. So many people jammed the pathway that is no more than five feet wide, I could barely see the lovely forest beyond the arches.

We found it a bit monotonous. We cut out after about 200 meters onto a more open path that returned us to the entrance. What we also found were statues of hundreds of foxes. The Inari considered the fox as their messenger and the god of cereals. Some of the foxes had in their mouths a rice stalk.

In Japanese culture, the fox is considered sacred with the ability to possess humans by entering under your fingernails. (I am not making this up.)

Marina and I looked at each other, shrugged and went in search of a sanctuary. We found it.

Tofuku-ji

We got back on the jam-packed train headed to Kyoto but got off on the next stop. We walked through the quiet neighborhood, past a police station and down an empty street. We crossed a wooden bridge and passed under a huge gate, called San-mon, the oldest Zen main gate in Japan.

Tofuku-ji is what we imagined Japan would look like. Quiet. Beautiful. Peaceful. The renowned Buddhist priest Enni, believed to have introduced noodles to Japan from China, founded the temple in 1236 and to this day it hosts Zen meditation. It gives four lessons a month for beginners but it’s no tourist trap. It’s all in Japanese and you’re advised to get a translator if you want to know what the hell you’re chanting about.

We didn’t want to meditate. We wanted to sit and look in peace. You can do that at Tofuku-ji. It’s a series of brown and white pagodas set around a giant Bonsai tree.

Gardens were constructed in 1938. After paying 800 yen (€5), we walked past a beautiful sand garden raked in a circular pattern and a rock garden neatly arranged with moss in a chequerboard formation.

A long structure ran alongside the garden where a young couple posed in traditional garb: him in a long gray robe and her in a white and gold kimono. Marina and I took a seat and looked at the garden. We heard a creek gurgling nearby. Birds chirped above. If I had a chair and laptop I could write there all day – and much more eloquently than I am right now.

Instead, I opened my cellphone translator and learned a new Japanese word: shizukana.

(Tranquil.)

Arashiyama Bamboo Grove

The following morning, on a brilliant 70-degree day, we went to another “must see” on the Kyoto checklist. It’s what’s commonly called the Bamboo Forest. It’s a narrow path through a towering forest of bamboo stretching more than 120 feet in the air. It’s beautiful in its simplicity, I read. So majestic in person, you’ll be disappointed with the photos.

It’s in Arashiyama, a town of 50,000 six miles (10 kilometers) west of Kyoto. We boarded a city bus that wound its way through the Kyoto that tourists don’t see: Corrugated fences. Drab houses. Charmless Honda dealerships.

After 30 minutes the bus stopped by a river where Arashiyama was abuzz with scurrying tourists. Lining the main drag were souvenir shops selling everything from bamboo wall hangings to, admittedly, addicting pecan cookies.

We followed the mob up the street until we saw the entrance. Two massive, thick walls of green bamboo flanked a narrow path. We squeezed in between thousands of people. So touristy, part of the path was widened into the forest in order for tourists to snap selfies.

Any tranquility from the majestic tower of bamboo was lost in the caliphony of chatter and snapping cell phones. The lone highlight was an old Japanese man selling beautiful, handmade postcards featuring Mt. Fuji. The man smiled and chatted with everyone, having a pointed comment about everyone’s country. Marina told him we were from Rome.

“BuonGIORNO!” the man said with a big smile. I bought four postcards for my wall and re-entered the human wave.

After 15 minutes, it spit us out above the forest where we saw an entrance to a villa. Feeling let down by a site that was more eye sore than iconic, I had no enthusiasm to pay to see someone’s old home.

I reluctantly paid 2,000 yen (€12) for two tickets. Just as Tofuku-ji saved us from Fushimi, the villa saved us from the Bamboo Forest.

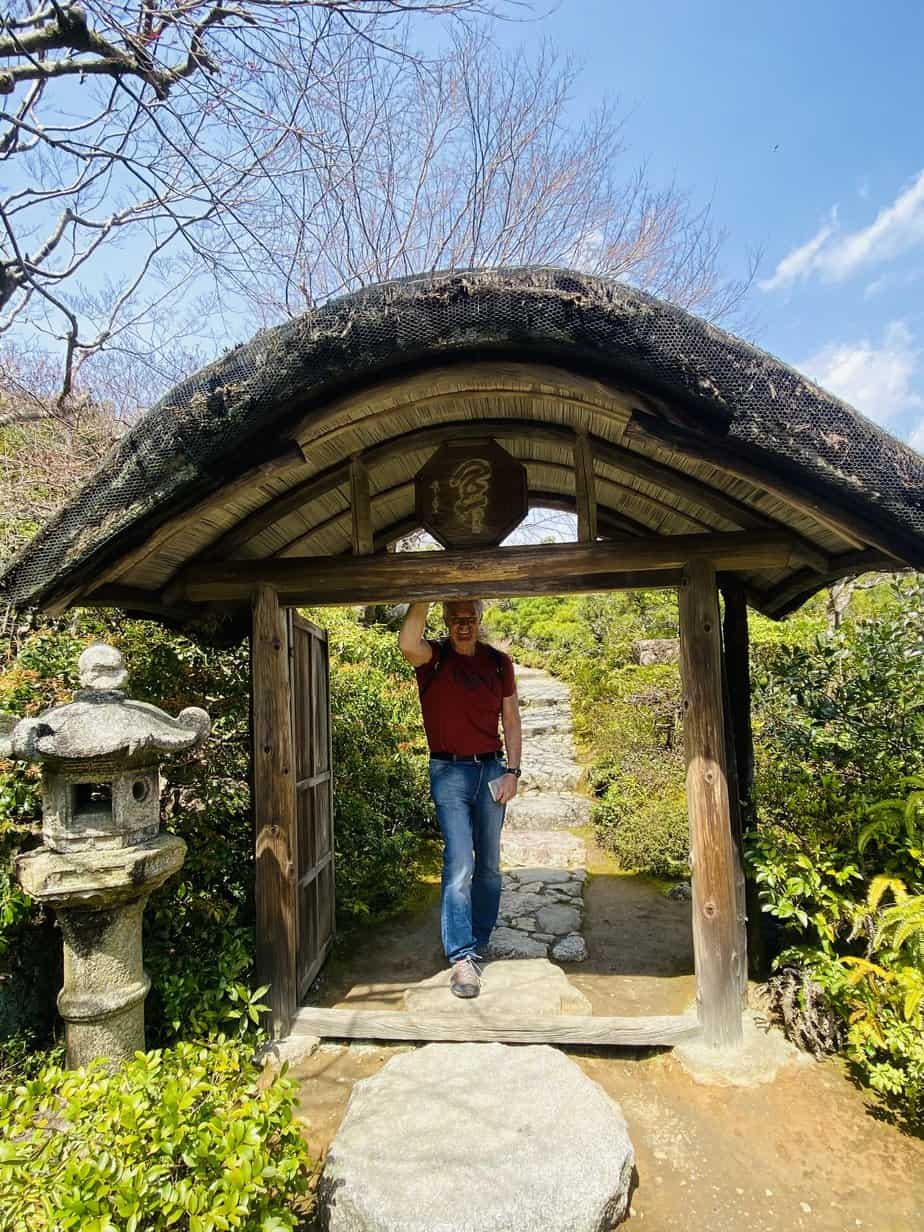

Okochi Sanso Garden

Denjio Okochi was a famous actor in Japanese films from the 1920s through the ‘50s. He became famous for his roles as a swashbuckling sword fighter and in World War II films during the war.

After surviving the Tokyo earthquake of 1923 that killed 142,800 people, Okochi had a dream of building a shrine in a quiet part of the country. During the ‘30s and ‘40s at the height of his fame, he built a huge villa above the forest on the slopes of Mt. Ogura. He often came here for inspiration through meditation and prayer.

It opened to the public after his death in 1962 and is maintained as if he would come back any day.

As we passed the ticket booth, we sat in a big tea house with just a few people. The bitter tea seemed apropos for the lousy day I was having. However, as we toured the grounds, the day became very sweet.

A stone pathway meandered up the hill. With each turn we saw a new view of the gardens and Kyoto below. We soon came to his main house. Built on stilts, it sports a big wraparound balcony looking out over Kyoto and Mt. Hiei-zan and Mt. Dainon-ji beyond.

If the weather had cooperated and more cherry blossoms were out and if snow remained on the mountains, this wouldn’t be a villa. It would be a priceless tapestry in a Tokyo museum.

Continuing up we passed a stone pagoda and a little stone opening where two Japanese women ate lunch out of a bowl with chopsticks. Birds chirped

Farther up, we saw a guest house with tatami rugs in the bedrooms.

During our hour meandering among the gardens, houses and views, we saw maybe 10 people.

We then made our long walk down to town. The bus we took had just disgorged another mob toward the Bamboo Forest.

In two days I felt cheated. But both days our wanderings were rewarded. Welcome to Kyoto.

(Coming Tuesday: Japanese cuisine.)

If you’re thinking of going …

How to get there: The Shinkansen leaves from Tokyo every 10 minutes and costs €85 one way. Kyoto has Kansai International Airport but is more expensive than flying to Tokyo and often requires two connections. Tokyo takes more direct flights.

Where to stay: APA Hotel Kyoto Ekihigashi, 552-1 Higashi Shiokoji Cho, Shimogyo Ward, 81-075-354-4111. Modern, 10-story, three-star hotel a five-minute walk from Kyoto Station. Near good, local restaurants. I paid €663 euros for four nights, including a good buffet breakfast.

Where to eat: Will cover in Tuesday’s blog.

When to go: Spring and summer. March through May highs average between 56-77. September-November it’s 63-84. Avoid July and August where highs are low 90s and more than 70 percent humidity.

For more information: Kyoto Tourist Information Center, 2nd Floor Kyoto Station Building, 81-075-343-0548, 8:30 a.m.-7 p.m. Another is on 2nd Floor of Kyoto Tower.

April 12, 2024 @ 11:36 pm

Sorry you ran into crowds! We visited Kyoto & Tokyo on spring break 2018, and lucked into peak cherry blossoms. The locals make quite the party out of the event, staking out a spot in the park for the day and drinking a LOT. We avoided the bamboo forest based on other reports like yours. However, we experienced a smaller but still beautiful and tranquil version at Kōdaiji Tenmangū Shrine. We also visited Fushimi Inari-Taisha but arrived around 5:30pm on our return from Nara and it was not crowded at that time. We certainly weren’t alone, but were fortunate to get some photos of the Tori without tourists. If you go again, perhaps those tips will help. It sounds like you made lemonade out of lemons in each case though.

April 14, 2024 @ 8:41 am

Thanks for the note, Jim. We didn’t experience the hanami party, unfortunately. That would’ve been fun. Fushimi was truly awful, one of the worst travel experiences I’ve ever had.

April 13, 2024 @ 1:40 am

I first stepped through the large torii at the entrance to Fushimi Inari Shrine over three decades ago on a beautiful spring morning. Walking through the hundreds and hundreds of gates undulating over the hillsides, warm sunshine dappling the fresh green leaves, I was wrapped only in quiet nature and encountered few other people. At one point I became aware of incense wafting through the trees, and venturing further up a hill began to hear someone chanting at one of the small shrines. After passing passed by quietly I made my way back down the hillside and exited the shrine, blessed with an experience I have always remembered as magical.

I haven’t returned in recent years, having read how mass tourism and the ego-driven need to rush to crowded “must-see” venues and snap ever more selfies have destroyed the atmosphere that once defined the place. Really sorry to read you had such a dismal visit, but happy you at least managed to salvage your Kyoto visit by venturing off the trail to see things others are so intent on overlooking.

April 14, 2024 @ 8:38 am

Great story, Tom. And I’m truly jealousy you experienced Fushimi the way it was intended. Maybe I’ll take the first morning train there next time.

April 13, 2024 @ 9:18 pm

Great article John. I did Japan for 21 days last May and was impressed with the general state of orderliness and cleanliness, certainly a rules based society. A suggestion for seeing the Fushimi Inari is to take the first morning train out of Kyoto and then double back to the Tofuku-ji on the way back. Understandably an early day, but the only way to see Fushimi without massive crowds. Would also highly recommend the Nishiki food market. Thanks again!

May

April 14, 2024 @ 8:35 am

Thanks, Tony. Next trip will be spent more in Tokyo then the north. “Abroad in Japan” made the north seem pretty cool, if you can avoid the earthquakes and tsunamis.