Abortion: Americans vote today with rights in the balance, Italians wonder what will happen to theirs

Americans go to the polls today and the outcome will likely send states’ abortion laws reeling back to 12th century Persia’s. Since the Supreme Court’s overturning of Roe vs. Wade in June, 13 states have already banned it. If the Republicans win most of the midterm elections as projected, more states will follow. The Center for Reproductive Rights predicts 25 states will ban abortion.

Since June I’ve thought how odd it is that I live in a country that’s the center of the Catholic Church yet women in Italy have more rights than many of their American sisters. Even Saudi Arabia’s have more.

However, many in Italy are wondering how long that will last.

September’s victory of the far-right Brothers of Italy party (FdI) has Italy’s sizable pro-choice faction on edge. New prime minister Giorgia Meloni, whose party won on an anti-immigration, pro-family ticket, swears she won’t change the abortion law established in 1978.

However, she said she wants to “enforce fully” the law by supporting an “alternative to abortion.”

The FdI intends to offer cash incentives for women to change their mind about abortion and give birth instead. The FdI already backed a €400,000 fund in the Piedmont region to give cash to 100 women who abandon their abortion plans.

It would allow pro-life advocates to enter family planning clinics. Some regional authorities in health care are increasing funding and providing space for anti-abortion organizations in family planning clinics and hospitals.

Said FdI senator Lucio Malan to Politico: “While of course they can’t be allowed to harass people, we should allow them to be present, to show that abortion is not the only solution.”

You could see this happening after the election when Italy slowly began teetering right. Far right. Ignazio La Russa, who collects fascist memorabilia, was elected speaker of the house. Lorenzo Fontana, also anti-abortion and anti-gay, was named speaker of the lower house.

Mario Adinolfi, head of the right-wing Popolo della Famiglia pro-life party, said his group is “ready to ride the wave from the USA in a fierce battle ground against the right to kill a baby in the womb.”

In less than five months, Italy’s new government has not only rattled women’s security but raised the conservative voices stifled until now.

“We are absolutely concerned,” said Loretta Bondi’, president of Archivia, an independent library of the women’s movement housed in Casa Internazionale Delle Donne where she has worked for years. “The reversal of Roe v. Wade sent waves all over the world. Italy has been affected as well, particularly because we have this new government whose core is composed of people who are really completely committed to undermining women’s rights that we have fought for for decades.”

Meloni had barely flashed her impish smile on the victory stand when an estimated 1,000 people marched in both Rome and Milan in protest of the feared changes.

Bondi’, who also worked for United Nations Human Rights, is particularly appalled by Meloni’s cash prizes to women who change their mind.

“It’s so patronizing,” she said. “It’s like women can not decide for themselves what’s best for them. Women arrive to this decision to have an abortion after a long soul searching. The process is not painless. So I really doubt that cash incentives would reduce women to forgo this option. What they mean, however, is the attitude toward women in this country who’ve shown a maturity and depth of thinking that is really respectable are still patronized.

“The thing that really bothers me is it’s a woman who’s patronizing other women.”

This all is happening on top of the overbearing presence of the Catholic Church. Its influence has resulted in nearly 70 percent of all doctors in Italy refusing to perform abortions by declaring themselves “conscientious objectors.”

Abortion history in Italy

First, a little history.

Before 1978, the crime for abortion in Italy was two to five years in prison except in cases of endangerment to the woman’s health. Still, illegal abortions were rampant.

Then the women’s movement hit Italy in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. Women loudly protested for changes, and in 1978 the government established Law 194 in which “the state guarantees the right to responsible and planned parenthood.”

Abortions are allowed the first 90 days for reasons of “health, economic or social circumstances when conception occurred.” They are allowed in the second trimester if the woman’s life is at risk or if the fetus has genetic or deformities which would put more psychological or physical strain on the mother.

A period of seven days is provided, but not required, to meet with medical authorities before the abortion. Women must be 18. Younger girls can ask a judge for permission without their parents’ consent. In 1981 a repeal was considered but rejected by 68 percent of the vote.

No repeal was needed. In 1983, abortions in Italy reached a peak at 390 per 1,000 live births and the number has dropped every year since. In 2018 it was 174 per 1,000 births.

Access still a concern

However, legalized abortion doesn’t mean problem solved. In Italy it’s different. The law doesn’t require doctors or clinics to perform abortions and 68 percent of Italy’s gynecologists have declared themselves conscientious objectors.

That’s overall.

Here in rural Southern Italy it’s worse. In the region of Molise it’s 96 percent. In Basilicata it’s 88 percent and Campania 77 percent. In Rome’s Lazio region it’s 74 percent. The only Italian region that’s under 50 percent is 18 percent in Val d’Aosta, Italy’s smallest region with only 123,000 people.

In other words, only three of 10 gynecologists in Italy will perform abortions.

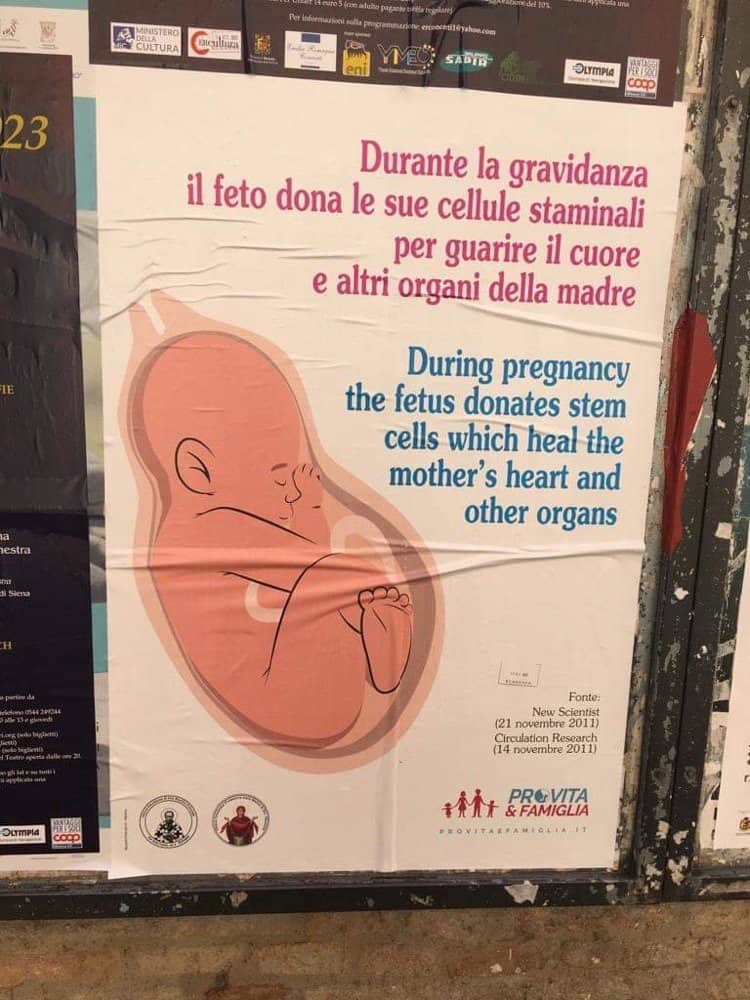

“Catholic organizations have a lot of money,” said Giovanna Scassellati, a gynecologist at Rome’s San Camillo Forlanini Hospital. “They start to show big images of a child in the street. It’s horrible. They pay to put these all over the town.”

While the Vatican can not change Italian law, it can influence its hospitals and public thinking. The Catholic Church has developed strong links with regional health authorities. It has diverted health funding from public hospitals to Catholic hospitals.

Many heads of hospitals and gynecology departments are influenced by the church and are pro-life. The hospitals’ doctors become conscientious objectors, not always because they’re against abortion but because performing abortions could hurt their career advancement.

Elisabetta Canitano, a gynecologist and president of Vita di Donna, an abortion-rights non-governmental organization, told Politico in May, “The church wants the poor to keep having children as it depends on state contracts to carry out charity work.”

So where does one get an abortion in Italy? Right around the corner from me.

The abortion hospital

As a staunch, lifelong pro-choice advocate, I find it ironic I live near arguably the biggest abortion hospital in Italy. San Camillo averages about 2,500 a year.

On Monday I walked the three blocks to the hospital. It’s been a well-worn path ever since I moved to the Monteverde neighborhood, reached my mid-60s and needed more medical care. I met Giovanna Scassellati at the hospital’s bustling coffee bar near the entrance. Still wearing her white gynecologist smock, she told me about her time years ago at Civita Castellana, a small hospital in Bracciano, about 30 miles (47 kilometers) north of Rome.

She was not allowed to perform abortions.

“It was a really bad situation,” she said. “It was a horrible chief. He was the chief of the hospital and gynecology. He tell us, ‘You have to know to be the doctor and then you have to be a gynecologist.’ Because in gynecology they don’t tell you much.”

Scassellati said almost no medical schools in Italy teach gynecologists how to perform abortions. She said one in Milan devotes only 10 hours of instruction over a five-year period. Many doctors come to San Camillo to learn the procedure. Scassellati learned in France in the early 1970s.

I asked her if she’s worried that the new government will change the law.

“I don’t think so,” she said. “They want to recognize the fetus as an individual person. This is the (risk). If the embryo is a person, the law stops.”

What would happen then?

“The women can go to the government to fight if they stop the law,” she said. “Like in America, it’s possible also in Italy. But the law is not very good for us if women have to go outside the country to do an abortion after 20 weeks.”

Almost on cue, a prime example walked by our table. Silvia, a doctor at San Camillo, overheard our conversation and told me her story. Four years ago, ultrasound revealed she had a perfectly healthy fetus. Then in three weeks, the ultrasound revealed the fetus had a cerebral hematoma, a fatal symptom within 45 days after birth. She was 35 weeks pregnant.

The Catholic hospital in Rome, Gemelli University Hospital, wanted to wait until 38 weeks, do a Cesarian and operate on the infant. Silvia, knowing her child’s fate, wanted an abortion.

“I felt abandoned,” she said. “And I was very angry.”

Instead, a week later she flew to Belgium where Brugmann University Hospital gave her an abortion free of charge.

“They were very clear,” she said. “They told me, ‘The baby is lost. We have to protect you. This is also the reason you don’t have to do a Cesarian section. You don’t have to have any mark on your body to remind you of the death of your baby.’

“I did not feel any pain because my psychological pain is too big.”

Babies and fascism

What’s the real reason Italy’s new government is applying pressure? Meloni bristles when her party’s fascist roots are mentioned, but changes in Italy’s abortion scene are similar to what another Italian politician did.

Benito Mussolini.

Italy of today and Italy of the 1920s have similar circumstances: A declining population. According to United Nations Population Division, Italy’s birth rate (the average number of children per woman of child-bearing age) this year is 1.3. That’s 189th in the world. Only Bosnia and Herzegovina, Singapore and Puerto Rico at 1.2 and South Korea, at 1.1 , average fewer. (The U.S. is 133rd at 1.8.)

There’s a good reason for this. Italy is still going through its worst recession since World War II. Many jobs are tied to temporary contracts and the lack of job security, as well as the lack of affordable child care, make parenthood a risky endeavor.

Also, Italian women have evolved. Being mothers is no longer everyone’s chief goal. They know they can have a good job and without children or a husband, they can have a good life and still have enough money to spend two weeks in Sardinia with their friends every summer.

The FdI won primarily on its anti-immigration stance. Many Italian conservatives fear the country is losing its population. Since 2002, the percentage of immigrants in Italy has quadrupled to 5.1 million or 8.7 percent of the population.

It is not lost on me that I am one of them.

This isn’t new. In 2003, during my first stint in Rome, Pope John Paul II became the first pope in history to address the Italian Parliament. His message: Have more children.

Mussolini said the same.

In his quest to return Italy to the dominating glory of Ancient Rome, he wanted to increase the population. Starting in 1927, he wanted to go from 40 million to 60 million by 1950.

In a campaign called Battle for Births, here were some of his measures:

- He banned contraceptives.

- He offered loans to married couples. Part of the loan was canceled with each child.

- Any man with more than six children paid no taxes.

- Bachelors’ taxes were increased.

- Starting in the late 1930s, civil services only recruited and promoted those who were fertile and married.

- The state railway fired all women employed since 1915 except war widows.

- Companies reserved promotions for married men.

It didn’t work. By 1950, the population had risen to only 47.5 million.

My stance

I was the last of three children and from what I gather, I was an accident. I’ve always joked that if abortion was around in 1955, I might not be here right now. I’ve actually had pro-lifers ask me, “Well, aren’t you glad your parents didn’t abort you?”

I respond, “Oh, you bet. If I’d been aborted, I’d be really pissed off right now.”

Come on!

If pro-lifers think abortion is killing a child, then an unwanted child can kill the mother’s life. The father suffers, too. I always imagine this: A high school honors student heading to an Ivy League college goes to her prom with her boyfriend. Afterward, the condom breaks and she gets pregnant.

She must derail her life, or even her college life, to give birth to a child she doesn’t want? The man must give up his dreams to get a job and support the child?

Pro-lifers’ fallback is adoption. It’s the answer for everything. But no one is lining up to get a crack baby or one born in a trailer park. Besides, I always ask …

… how many pro-lifers have adopted children?

I asked Bondi’ of Archivia what she tells pro-lifers who say abortion is murder.

“I’d say first of all they don’t know what they’re talking about,” she said. “Second, possibly these pro-lifers have never had an abortion themselves. Possibly these pro-lifers are not even women. I’d say, ‘You’re wrong. Get lost.’”

November 8, 2022 @ 3:02 pm

Great article, John. Thanks for covering this critically important issue. It’s depressing to see how the anti-woman political hacks who sit on the U.S. supreme court have influenced Italian politics, inspiring and emboldening the far right in Italy to deny women a fundamental right. I hope this new government in Italy lasts as long as most other governments have.

November 9, 2022 @ 2:56 pm

Interesting having the perception that Italian politics is influenced by the deliberations of the U.S. supreme court, that diminishes Italian politics to that of a puerile condition that needs a colonial master. Reminder the USofA is the politically immature new kid on the block.

November 8, 2022 @ 6:57 pm

I’m so glad you wrote this. However, I’m left wondering if most abortions in Italy are medical abortions, in other words obtained through prescription drugs rather than surgical procedures. That’s the case in the US and my understanding from what I’ve read in the NYT and WashPost is that a vast network is springing up underground to get the abortion-inducing drugs to those who need them in red states. Given the disparities in access that you describe in Italy today, it seems a similar solution might work here to circumvent the politicians.

November 9, 2022 @ 1:53 pm

An intrusive and patronising culture war article, reminiscent of a zealous advocacy incident that of all places played out on a hot and crowded Circumvesuviana train journey. Where an American family hubristically lectured the local juveniles on the virtues of their Silicon Valley tech – not so much bible bashing as tablet bashing – superiority evangelism all the same.

The sensationalism to post pics of Benito Mussolini and Giorgia Meloni must be overwhelming.

November 10, 2022 @ 3:14 am

On Italy’s demographic Armageddon, God forbid that a future visit to Rome will find it populated by WASPs whiling away their senior years.

November 20, 2022 @ 12:48 am

Oh you’ve got this right! I knew this pos in college and he was misogynistic way back then.