Anzio: Nero’s birthplace and site of key WWII battle is a beachside paradise a short ride from Rome

ANZIO, Italy — You can’t tour Rome and Southern Italy without being in awe of the monstrous footprint this civilization laid down 2,000 years ago. Monuments and market places, mausoleums and temples, the most powerful civilization in man’s history stretched from what is now Great Britain to Persia. Peoples and armies in between cowered with the very rumor that the Roman military drew near. They feared Rome’s red and yellow colors like the pestilence and the Plague.

Yet visitors often forget that during World War II, Italy was less of a power than it was a punching bag. Invaded by the Germans, bombed by the Allies and led by a fascist, Italy was a pockmarked landscape in desperate need of a helping hand. In the European theater, Italy was Les Miserables.

Unlike the fall of the Roman Empire, however, Italy had a happy ending in World War II. While the two events are about 1,500 years apart, history buffs can walk through both eras, see the ecstasy and the agony, in one small city. The town of Anzio 30 miles south of Rome has a population of 54,000 hard on the Tyrrhenian Sea. It has a lovely harbor rimmed with lip-smacking seafood restaurants, no traffic, a clean sea, a sandy beach and a relaxed seaside vibe. Anzio looks airlifted from the Greek isles.

The history

But it’s Anzio’s history that attracts people. In the 3rd century A.D., on the same beach where people flock to sunbathe six months a year, stood a colossal villa that made Mar-o-Lago look like a youth hostel in Des Moines. And you know its chief inhabitant: Nero, Anzio’s star-crossed son and arguably the most controversial emperor in Roman history.

Near where he entertained guests in a grandiose palace is the site of the Allied forces’ invasion in 1944 that led to the liberation of Rome and, eventually, the end of World War II. Evidence is everywhere, from a fabulous war museum to photos of a famous rock star whose father died in those bloody six months 77 years ago.

In lieu of world travel, and with the probability of another national lockdown as the Covid pandemic in Italy worsens, Marina and I continued our exploration of Rome’s underrated Lazio region. Anzio is an easy reach from Rome. We drove 45 minutes down an uncrowded two-lane highway mostly lined with the tall, majestic Mediterranean pine trees. On a 60-degree day with the sun out and the windows down, we could smell the salty sea air as we entered the city. It has been mostly rebuilt since the war with a modern grid street system but the streets are clean, a pleasant revelation after the overflowing dumpsters we left in Rome.

Greeting us were Patrizio Colantuono and Mauro Agostini, two kind, elderly gentlemen who are Anzio’s de facto history experts. Patrizio runs the war museum and Mauro is a former air traffic controller who is an Ancient Roman history buff. Two bookends of 2,000 years of history.

Mauro took Marina and me down some steep steps to a beach that’s as sandy as any in the Caribbean if not as white. It’s the start of spring here and a half dozen people were scattered around, exploring the beach, catching some rays, killing time on a nearly empty, lovely corner of Italy. The sea looked remarkably clear.

“Anzio is the only blue banner of Rome province,” Mauro said. “Blue banner is the graduation of blue, in reference to the environment.”

Marina and I spend Rome’s hot summer months exploring the nearby beaches of Lazio: Sperlonga. Sabaudia. Fregene. Gaeta. We’ve been on most of them. Anzio, the site of one of the deadliest World War II battles in Italy, is the cleanest of them all.

Which is probably why Nero decided to expand a series of buildings started here in the 2nd century B.C. Imagine the water quality back then before the first cruise ship. Then again, Nero only wanted the best. It’s why he’s still considered Anzio’s favorite son, despite his name being a four-letter word to historians for more reasons than one. Above the beach stands Nero’s statue, pointing north up the coast.

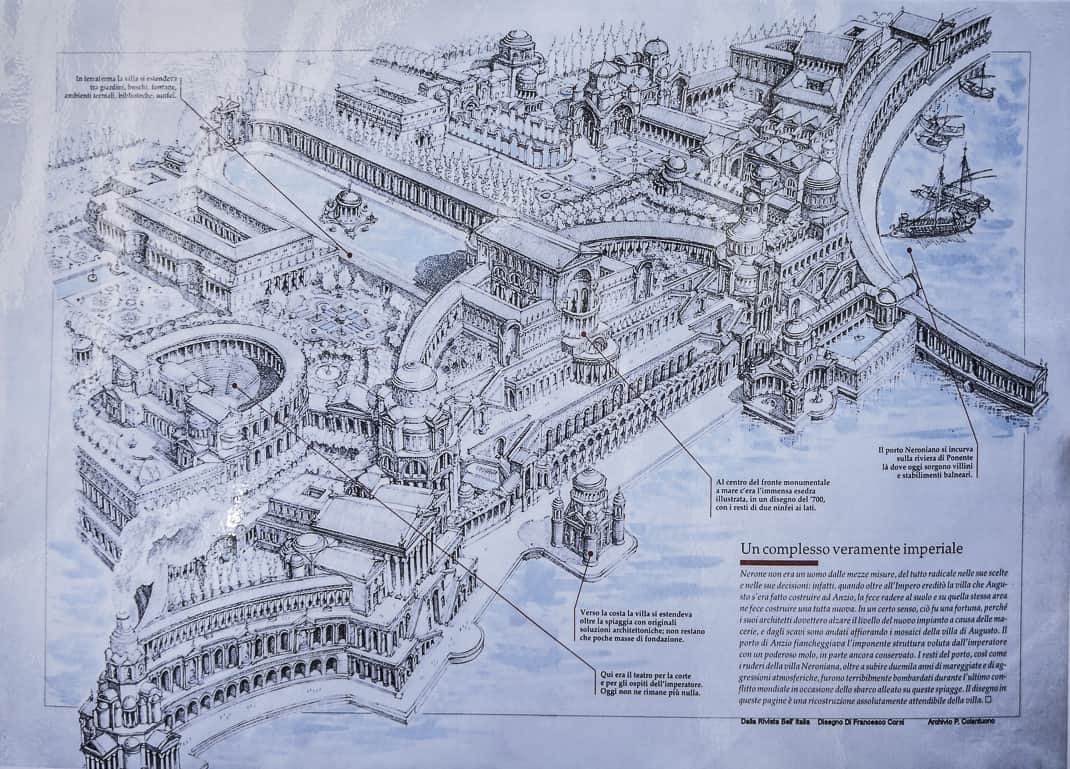

We walked up the beach and looked to our right and saw atop the cliffs the stone remains of Nero’s villa. A series of archways. A long wall. Brick remains of water heating conduits. Then Mauro handed us a highly detailed laminated drawing of what Nero turned the villa into 2,000 years ago.

Combine the Atlantis resort in the Bahamas with the King of Brunei’s palace and you have Nero’s villa. It stretched 800 meters along the sea and 300 meters inland. That’s 2.6 million square feet. That’s three times the size of Buckingham Palace.

It featured an endlessly long porticoed wall in the front where Nero entertained his guests. Flanking it atop the water were little villas where guests could fish or swim off their deck. Behind it on an upper level stood a tall, narrow building with a semi-circular balcony overlooking the sea. Farther inland was a large amphitheater and beyond it was a huge pool with a columned gazebo in the middle.

“It was full of gardens, statues, nymphs (statues),” Mauro said. “And it was all covered with white marble like the Colosseum. You see the skeleton of the Colosseum (today). Here it was about the same.”

The sea, 2,000 years ago, came 25 meters farther inland. It’s why Anzio’s beach is so wide today.

“Consider that once there were buildings like in Venice here,” Mauro said. “It was built very close to the sea.”

Nero didn’t spend most of his time here. He was too busy forming cracks in the Roman Empire and killing everyone in his way when he wasn’t shtoinking the local help. Nero was born into power in Anzio in 37 A.D. Emperors Caligula (37-41 A.D.), also born in Anzio, was his uncle and Claudius (41-54 A.D.) was his great uncle. Claudius adopted Nero as his heir apparent and Agrippina, Nero’s mother and Claudius’ niece, did what she could to reap the power from her eventual emperor son: She poisoned Claudius with mushrooms.

Nero was 16.

His mother appointed actual adults to handle the governing while Nero pursued his other interests: poetry, acting and girls. Taking on a greater role later, Nero became unhinged with power. He twice tried killing his mother for meddling into his personal affairs, succeeding the second time only after she swam safely to shore when her sabotaged ship broke down while crossing the Bay of Naples.

He executed one wife for adultery and kicked his pregnant second wife to death. However, he apparently was quite popular in his concubines. Meanwhile, the Roman Empire, which Nero had expanded with the exploration of the Nile, was beginning to falter as his megalomania expanded.

The great fire

Then the great fire broke out in 64 A.D. and most of Rome went up like a pile of stale fettuccine. He blamed it on a new religious sect called Christianity. He executed as many Christians as he could by crucifying them, burning them alive and covering them in animal skins and siccing wild dogs on them. Then he drank wine.

Becoming more paranoid, he tried executing everyone he suspected of conspiring against him which made meetings with his senate somewhat awkward. The Roman aristocracy declared him enemy of the state and he fled Rome, his toga flying in the wind. As the mob approached, he stabbed himself to death. He was 30.

History recalls him as one of Rome’s worst emperors, topped only by his randy uncle Caligula, whose idea of urban renewal was turning his palace into a brothel. But Massimiliano “Max” Francia, my favorite tour guide in Rome (guideromax@virgilio.it), has always said Nero wasn’t as bad as history claims. He said people still bring flowers to his tomb in Rome on June 9, the anniversary of his death.

“In the poor and common people’s view, Nero was a great emperor, for he spent large amounts of money on food and games to entertain the mob,” Max wrote me in an email. “Since he had this money taken away from senators with absurd excuses, senators did not like him.”

But shouldn’t he be at fault for Rome burning under his watch?

“When the great fire blasted, Nero was in Anzio,” he wrote. “The historian Tacito says that Nero rushed back to Rome to help firemen extinguish the fire. The point is the following: Who were the ones attacking the firefighters to prevent them from controlling the fire and have Rome destroyed? Jews, Christians, men of Nero?

“Nero cast the blame on the Christians and had the first persecution unleashed.”

Modern history

The villa fell into decay and during the Middle Ages many people left Anzio for Nettuno, another beach town two miles to the east. At the end of the 17th century, Pope Innocent XI and Clement XI restored Anzio’s harbor just to the east of the old one where it remains today.

In World War II Anzio made international history again. In February 1944, German soldiers surrounded American GIs in caves in Pozzoli. On Feb. 18, two German torpedoes sunk the British ship Penelope off Naples and 417 died. Among the dead during the Battle of Anzio was a British lieutenant named Eric Fletcher Waters whose son, Roger, would become a decent bassist of note for a rock band called Pink Floyd.

Allied forces needed a strategy. They wanted to outflank the Germans, who were occupying much of the area east of Anzio, and continue their march to Rome. The Allies had an amphibious landing on Anzio’s marchland and faced no opposition. German field marshal Albert Kesselring, in response, moved into a defensive ring around the beachhead. He stopped the gas pump and flooded the marsh with salt water hoping an epidemic would wipe out the Allies.

He asked Adolf Hitler for more troops and soon 300,000 were around Cassino 80 miles to the east of Anzio. Germans bombed Anzio for weeks. But major general Lucian Truscott got the Allied troops out in May and headed to Rome which it captured from the Germans on June 4.

I know that day well. Marina is a third-generation Roman whose father told me when he was 8 years old, he went into the city center and picked up chocolate bars the Allied soldiers threw from their tanks. The chocolate tasted especially good. The Nazis had imprisoned his father for 10 days for suspicion of communism.

Anzio’s cemetery

But the Allied victory’s cost was massive. In the Battle of Anzio from Jan. 22-June 5, 90,000 soldiers died. One of the biggest World War II cemeteries in the world is in Nettuno which houses the remains of 7,860 American soldiers. As we entered Anzio, we quickly came across the Beach Head War Cemetery. It has the graves of 1,056 soldiers, nearly all from the United Kingdom.

We passed through the gate and saw a beautiful plaque with a red wreath commemorating the dead. Engraved are the words “THEIR NAME LIVETH FOR EVERYONE.” Beyond a huge field of identical white gravestones stood a 20-foot cross.

I read inscriptions such as “P.C. Bowles, The Sherwood Foresters. March 20. Age 22.” “J. Roke. Age 20. May 23. The Green Howards” and the family’s inscription, “Too far away your grave to see. Not too far to think of thee. He did his duty.”

The Musei dello Sbarco di Anzio (The Museum of the Anzio Landing) built in 1995, is about 300 meters from Anzio’s train station. Patrizio greeted us and unlocked the doors which have been closed during this pandemic. Inside were big vases and mosaics from Ancient Rome but his proudest possessions are in his World War II room. Nearly every square centimeter is crammed with paraphernalia and news from the Battle of Anzio.

One portion of the wall is covered in war propaganda signs in Italian from both U.S. and German sides. One reads, “BUON SANGUE NON MENTE! (GOOD BLOOD DOES NOT LIE!)” Another shows a smiling Nazi soldier with the sign saying, “La Germania e’ Veramente Vostra Amica. (Germany is Truly Your Friend).”

There are photos of soldiers wading ashore on Jan. 22, of U.S. soldiers transporting the injured up brick steps to a naval hospital, photos of the bombed port. One case is filled with old bullets, many surrounding a used tube of Barbasol shave cream. One photo shows a Jeep rolling through a Rome street crowded with cheering Italians. The Jeep carries a makeshift wooden gravestone sporting a swastika and the words “FOR HITLER!”

There are mannequins in nurses uniforms and army uniforms and naval uniforms.

The museum has a modern touch, too. One section is reserved just for Roger Waters, the Pink Floyd bassist who visited in 2016. Dressed in a polo shirt, the 73-year-old Waters looks like a regular tourist. There’s a 2004 photo of former prime minister Silvio Berlusconi who visited.

Patrizio showed us a very good film, in Italian, of the Battle of Anzio. He proudly showed us books sporting more pictures of the visitors he’s received and the honors given to the museum.

These days the museum, Nero’s villa and beach aren’t Anzio’s lone attractions. Just go to eat. We ate lunch twice. Ristorante Turcotto has been at the same spot above the beach since 1816. Outside it even has a huge, grainy black and white photo from the 19th century.

It’s an elegant, airy restaurant with cream-colored tablecloths and big picture windows showing a balcony with three lone tables that are very difficult to reserve. Beyond was the navy blue Tyrrhenian Sea glistening in March sunlight.

I ordered something new: ravioli di spigola (ravioli filled with sea bass). Covered in rich tomato sauce and sprinkled with green onions, it was one of the best raviolis I’ve ever had.

Another day we went to Ristorante da Antonio al Porto, one of the many casual eateries ringing Anzio’s historic harbor. The wraparound windows show the port and a plant wraps its way around a column to the ceiling. We sat at blue and white checked tablecloths and I had the risotto alla crema di scampi (rice in a prawn sauce). It’s easy to screw up scampi, but the flavor of the prawns stayed on my tongue on every bite. With a Lazio Chardonnay, we couldn’t have ended a day in Anzio any better.

Anzio today

Like Nero, other Romans have discovered Anzio. In 30 years, the population has grown from 25,000 to 54,000. It grows to 200,000 in July and August when so many Romans come to their second homes which make up about 40 percent of the housing.

Antonio Terzuoli, the 50-year-old owner of Antonio al Porto, was raised in Anzio. He lived for 15 years in Sarasota, Fla., where he opened an Italian restaurant and returned to Anzio in 2008 when the financial crisis hit the U.S. He understands the appeal for Romans. He said comparing Rome and Anzio “is like comparing New York and Sarasota.”

“Basically if you live in Rome city, if you live on the south side of Rome and work on the north side, it takes you driving 45 minutes. Or if you take the train it’ll still take you 45 minutes. What do people do? They move from the city and live in Anzio, especially if you have a child. In Rome you have your house and have to drive 25 minutes to park your car. Here you have your parking in front of your house.

“Your wife has to bring your kids to school and must find a place to park, she has to fight traffic. One of the kids comes home in Rome they only play with the computer. Here they can go to the beach. You see they can walk around. When it’s a sunny day, kids can go play like in the old way, when we were kids 40 years ago. We’d play soccer and walk around without fear.”

Mauro, 72, moved to Anzio 10 years ago from Rome after exploring other towns around the city. Although he calls people in Anzio “a bit more rude” than Romans, he says the quality of life is better.

“The climate is a big difference in respect to Rome because of the influence of the sea,” he said. “Also, because I found here in Anzio other interesting activities linked to the archaeological museum and the BeachHead Museum. I’m able to pass the remains of my life with good activities.”

Hopefully, this pesky pandemic will leave us alone by summer and we can return to lay in the sand and dine in the sun. We can’t live like Nero but in Anzio, we feel like it.

If you plan to go …

Where are they: Nero’s Villa, Villa della Fanciulla D’Anzio, 39-06-984-99479. Museo dello Sbarco di Anzio, Via di Villa Adele 2, 39-06-984-8059, 39-349-455-6241, www.sbarcodianzio.it

How to get there: Trains leave for Anzio every hour from Rome’s Termini train station. Hour-long ride costs 3.60 euros one way. Exit terminal onto Viale Claudio Paolini and head downhill until you reach the water. Nero’s Villa is to your right. Museum is 300 meters from train station.

How much does it cost: Villa is free. Hours Sept. 15-May 30 10:30 a.m.-12:30 p.m. and 4-6 p.m., June 1-30 5:50-7:30 p.m., July 1-Aug. 20 4-8 p.m., Aug. 21-Sept. 19 5-7 p.m. Closed Monday. (Temporarily closed due to pandemic.) Best views are from beach year round. Museum is free, 10:30 a.m.-12:30 p.m. and 4-6 p.m., July and August 10:30 a.m.-12:30 p.m. and 5-7 p.m. (Temporarily closed due to pandemic.)

Where to eat: Ristorante da Antonio al Porto, Via Molo Innocenziano 38, 39-06-92-09-03-09, 39-333-54-02-933, Noon-3 p.m. and 7-10 p.m. (Hours shortened during pandemic). Ristorante Turcotto, Riviera Mallozzi 44, 39-06-984-6340, 39-06-984-5295, http://ristoranteturcotto.it. Sunday 12:30-3 p.m., Monday and Tuesday 12:30-2:30 p.m. and 7-10 p.m., Wednesday 12:30-2:30 p.m., Friday 12:30-2:30 p.m. and 7-11 p.m., Saturday 12:30-2:30 p.m. and 7-10 p.m. Closed Thursday. (Hours shortened due to pandemic.)

March 11, 2021 @ 6:28 am

well researched and written. Great job!

March 11, 2021 @ 12:20 pm

I so appreciate your history tour and review of the city of Anzio! There are so many places to visit near Rome but you have made this one a priority through the recount of your visit there!

March 11, 2021 @ 3:40 pm

Really interesting and well dove!

Excellent writing!!

Mauro

March 11, 2021 @ 3:40 pm

Well done..of corse!!

March 11, 2021 @ 3:42 pm

Terrible!!!…course

June 8, 2022 @ 9:20 pm

Nice article. My parents live in Anzio. Sadly, it is not what I would call a clean beach or town. You were there in March. In summer, as Romans flock to Anzio, their notorious mismanagement of trash and penchant for littering comes with them. The public sections of the beach, right by the Nero villa ruins, are often littered with trash. Broken glass usually litters the ground in those cool tunnels. Graffiti marks nearly every surface, just like Roma. I love the town, but cleanliness would not be its strong suit.

Sperlonga, which you mentioned, has banned all single use plastics in the town, does not condone graffiti, and is one of the cleanest beach towns I have seen in Italy. It is also “blue flag beach” certified, but honestly that is about water safety more than cleanliness and is a bit of a scam certification.

May 3, 2023 @ 9:58 am

HI. Just moved to anzio last year (2022). I see your comment valid problem, and also Sperlonga is amazing but as you said, it has much less people. Sperlonga is much further from Rome so people will go there for holidays but not easy to move/live there on long term. Rome provides a lot of services nearby you cant have in sperlonga. AGain all comes down what you want and prefer.