Belfast: The Troubles are over but a wary peace hangs over the most unique war zone on earth

(First of two parts)

BELFAST, Northern Ireland — I’m not a big guided tours guy, but I’ve taken enough during my travels to know that not many include this line from the tour guide:

“This is the most bombed hotel in Europe.”

We were passing the Europa Hotel, a 12-story monolith in downtown Belfast. It looks like many other four-star hotels in the world. Huge facade. Lots of glass. Big signage. It didn’t appear to show any damage from — get this — 36 bomb attacks. For nearly 50 years, from its construction in 1971, the Europa has been a 170-foot symbol of the Troubles, Northern Ireland’s 30-year civil war.

Marina and I like to get out of Rome for New Year’s Eve and what better place to party that night than Belfast? New Year’s Eve in Belfast just sounds drunk, doesn’t it? It’s the perfect formula: a city at peace enjoying a tourism-infused economic renaissance (See Part II later this week) — and an Italian girlfriend who’d never been drunk in her life.

However, my goal of preventing her from nursing a Guinness for an entire weekend was overwhelmed by the mind-numbing sights of the Troubles and the people who lived through it.

Our tour guide was one of those people. Patrick O’Byrne is a friend. We met in Rome last year while he was working with the European Union and started dating one of my language scambio partners.

O’Byrne, 53, was born and raised in Belfast and home for the holidays. He’s as Irish as a four-leaf clover on a leprechaun’s hurling stick. He refers to Northern Ireland as “the North of Ireland.” Londonderry, Northern Ireland’s second-biggest city, is “Derry.” Tattooed on his arm is the shamrock logo of Celtic FC, Glasgow’s Catholic-based soccer power in the Scottish League. He despises Rangers, Celtic’s Protestant cross-town rival. (“I’m a 90-minute bigot,” he says.) His name couldn’t be more Irish if you wrote it in green. Patrick O’Byrne sounds like a guy who could drink six pints of Guinness and sing “Molly Malone” on a St. Patrick’s Day float.

He lived through the Troubles and his memory hasn’t faded through 20 years of peace. A bomb blew out his family’s window. He suffered two broken noses in brawls with Protestants. He saw riots nearly every weekend. He knew guys who were kneecapped three times.

“It was just a dirty, dirty war,” he said.

Belfast, a city of about 500,000, was always on my bucket list. Like Albania, North Korea and Paraguay, Belfast was one of those places I wanted to visit because I never knew anyone who had. I just remember seeing black-and-white photos showing ratty-attired men hurling objects at other ratty-attired men and heavily armed soldiers hovering over fallen youths in hooded masks. In the background was always what looked like a tenement building. Rubble seemed everywhere. I read 300,000 military troops served in a city the size of Colorado Springs.

Tourism was not high on Belfast’s priority list. When your best hotel in town is bombed 36 times, Rick Steves isn’t showing up anytime soon.

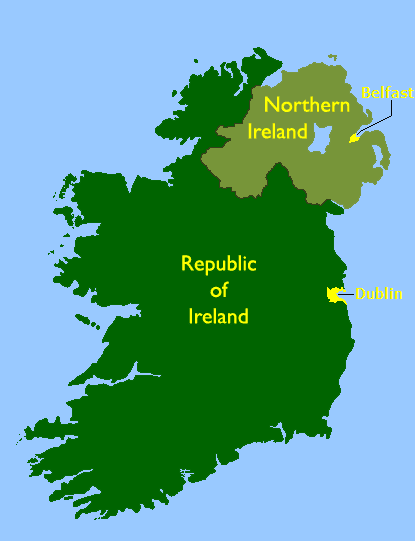

The basis of this conflict goes back 800 years and putting it in one paragraph is like tweeting the evolution of man. Suffice it to say Northern Ireland, populated a great deal by Scots who had also lost independence, was kept by Great Britain when it granted Ireland independence in 1921. While Northern Ireland is part of Great Britain, nearly half the people are Catholics who view themselves as Irish. They claimed they suffered discrimination and wanted a united Ireland; the Protestants view themselves as British and wanted to maintain that connection.

More than 3,500 murdered souls later, Northern Ireland is back where it started. The Catholics and Protestants have learned to maintain a relatively peaceful co-existence. Mixing is more common. Still, tension simmers beneath the surface. Tuesday’s Belfast Telegraph reported 71 victims of paramilitary-style assaults and shootings, including 20 deaths, in the 12 months leading to December. That’s more than one a week. The city’s problem is prosecution.

They can’t get survivors or witnesses to come forward.

The first thing I learned about the Troubles is to stop calling it Catholics vs. Protestants. This isn’t Notre Dame vs. Penn State. It has little to do with religion. It’s all about nationalism. It’s more accurate to call it nationalists or republicans (who consider themselves Irish) vs. loyalists or unionists (who consider themselves Brits).

During the Troubles, within those groups were:

The Irish Republican Army, the nationalists’ violent republican army.

The Ulster Defence Association, the loyalists’ paramilitary arm.

As we say in America, you can’t tell the players without a scorecard. In Belfast, you can’t tell the type of neighborhood without a really good map — or a good guide like O’Byrne. I’ve been to 100 countries. No city in the world is like Belfast. No city has party lines mapped out in such a quilt. You can be in a nationalists’ neighborhood, cross a street and be in a unionists’ ‘hood, go a couple more streets and you’ll be back among nationalists. During the Troubles it was like a white South Central L.A. Falls Road and Shankill Road made international headlines in the ‘70s, ‘80s and ‘90s as the nationalists’ and unionists’ strongholds, respectively.

They are less than a mile apart.

“That’s why sectarian murder was so easy,” O’Byrne said. “It was easy to pick off the opposition. If they were walking down a certain pavement, they were Catholic or Protestant. Sometimes they got it wrong.”

O’Byrne picked us up at our Clayton Hotel, one of the glittery high-rise hotels that have popped up in Belfast the last 10 years. It’s two blocks from the Europa, a good place for O’Byrne to tell his tale. He was born in a mixed neighborhood in North Belfast, the son of a bar manager and housewife. He went to sea and is semi-retired.

He took us by a building with a giant mural of a man in the kind of white wig you see on British courts. It was King William of Orange, the king of England and Scotland from 1689-1702 and who fought against the Catholic king of France, Louis XIV. This was Sandy Row, a small enclave and the most unionist part of downtown. Like all Northern Irish Catholic students during the Troubles, O’Byrne went to an all-Catholic school. But he went to a mixed college near here.

“I’ve drunk once on this road with a Protestant friend, a student,” he said. “He took me into a bar somewhere. I said, ‘Don’t call me ‘Patrick’ in here.’”

I noticed the lampposts sported red, white and blue striping. Near my hotel is a fenced-in construction area for the proposed George Best Hotel. Best is considered one of the best soccer players who ever lived and the most famous athlete Northern Ireland ever produced. He’s from East Belfast, near the docks. That’s 100 percent unionist territory.

Memorials are everywhere. One showed a fresh-faced young man smiling as if watching a soccer match.

“He’d been shot or blown up,” O’Byrne said. “He’s a local lad, probably from the street, who was killed by the IRA or UDA or shot by the British. The loyalists fought the British on occasion. The army and police were against both sides.”

We drove down Sandy Row and saw a man standing outside a pub. He looked like any other Belfast citizen. O’Byrne didn’t need to know what street he was on to know who he was.

“He’s got Northern Ireland shorts on and he just came out of a Sandy Row bar so he’s definitely a loyalist,” he said. “If you see a Northern Ireland shirt, it’s a loyalist. If you see a Republic of Ireland, it’s 100 percent Catholic.”

We continued around downtown and passed a bar called Lavery’s.

“One of my favorite bars as a kid,” O’Byrne said. “It’s right here by Sandy Row but it was a Catholic bar. A few times we got raided by these boys who’d come in and start fights. It’s a student bar. But these guys on Sandy Row took all students to be Catholics.”

I asked how he got along with the unionist students after growing up in segregated public schools.

“It took us a while,” he said. “We were standoffish then we said, ‘Fuck it. Let’s just go to the student union and get drunk.’”

We left downtown heading west and I noticed something. The signs on buildings and walls were bilingual: English and Gaelic, the Irish language taught in Republic of Ireland schools and Catholic schools in the North. We were on Falls Road, as synonymous with Belfast during the Troubles as hunger strikes and pub bombs.

Gaelic was the second language on the walls. O’Byrne is far from fluent but knew this translation: “Tiochfaiah Ar’ La’” (“Our Day Will Come”). Another in English read, “You can kill a revolutionary, but you can never kill the revolution.”

“Nationalists were second-class citizens for the first 50 years of the Northern Irish state,” he said. “Violence erupted in 1969 because of the suppression of the civil rights movement. That suppression led to the resurgence of the IRA and the Troubles.”

At the end of the block is a huge iron gate, swung open for cars to pass. During the Troubles it was often locked.

Further down the road, near a Sinn Fein office, is a giant mural of the face of the revolution. Covering the entire side of a building is a bright color mural of Bobby Sands. If you didn’t know his name, you’d look at his long, flowing hair parted in the middle and his huge smile and think he was a fifth Beatle. He wasn’t. He was the republicans’ leader who died in prison in 1981 during a hunger strike in which he didn’t eat for 66 days. He was 27. He inspired other hunger strikes that cost the lives of nine other nationalists.

While O’Byrne said, in retrospect, the hunger strikes didn’t work, he said, “At the time I supported them. As a 16-year-old I absolutely supported them.”

We got back in the car and drove past Royal Victoria Hospital, the biggest hospital in the city and home to what O’Byrne says are “the best knee surgeons in the world.” Why here? They were needed. The IRA distributed punishment for petty crimes.

“If you were seen talking to the police, you were viewed as an informer and were shot,” O’Byrne said. “Back of the knee.”

We headed north through his old neighborhood and east where the shipyards made the biggest ships in the world, including the Titanic in 1911. The shipyards provide 100 years of bitter memories for Catholics who were never hired. It’s not funny but some of the jokes that emerged from the discrimination were.

“The dock workers were 100 percent Protestant workers,” O’Byrne said. “What were they doing in West Belfast when the Protestants were in East Belfast building the Titanic?

“They were building an iceberg.”

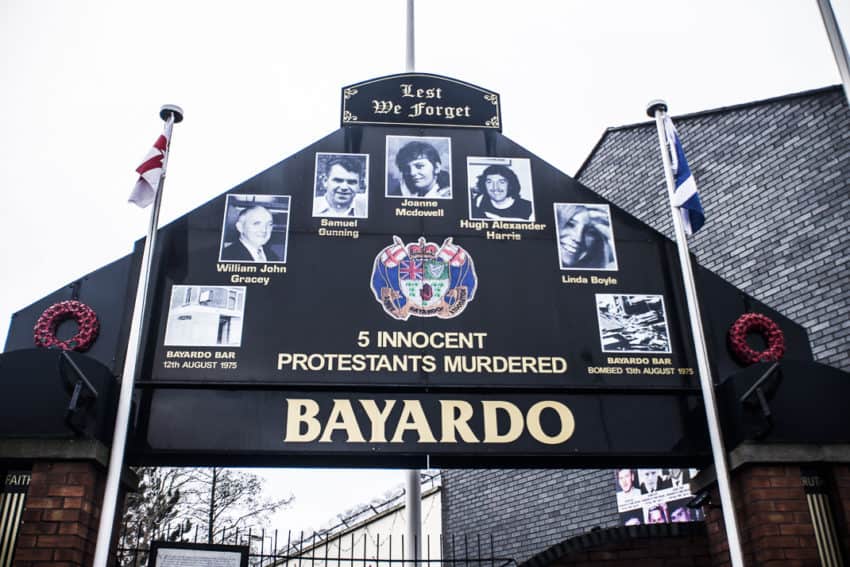

Time, however, has somewhat softened O’Byrne. Jokes aside, he no longer waves the IRA flag. He knows the destruction it once wrought. He drove us down Shankill Road, the unionists’ epicenter. One corner is an open-air memorial to Bayardo, a pub the IRA blew up in 1975. On the memorial arch are the words, “5 INNOCENT PROTESTANTS MURDERED” with their pictures above. Behind it are gruesome photos of the carnage IRA bombs left in London and Paris among other cities. Under one reads: “IRA — Sinn Fein — ISIS no difference.”

I ask O’Byrne what would you say to a loyalist who said, “You were shit and terrorized the community”?

“I’d say, ‘We did,’” he said. “But you did the same to us.’ No community suffered more than the other.”

Every tale has two sides, however. In Belfast you don’t have to go very far to get it. It’s not much farther than going to a visiting team’s locker room. One Saturday morning all I had to do was walk three blocks from my hotel to City Hall. Belfast’s City Hall is one of the most magnificent buildings in Great Britain (or Ireland). Built in 1906, it covers 1 ½ acres and features four towers and a 173-foot copper dome. It dominates Belfast’s modest landscape like a castle over a vineyard.

Standing in front of it were a small group of people carrying the UK’s Union Jack flag. I asked one of them, Billy Dickson, 71, a Belfast native, what the peaceful demonstration was about. In 2012, the Belfast City Council ruled that the flag that had flown over City Hall would only be flown on statutory days such as the Queen’s birthday and national holidays.

It’s no coincidence that Sinn Fein is now in Parliament and Belfast last year elected a Sinn Fein mayor, Deirdre Hargey.

“They alleged that some people found it offensive to have the flag of our country to be flying,” he said. “It’ll fly about 15 days a year, 20 at most.”

For the last seven years, a group of unionists have come here every Saturday, from 1-2 p.m., to wave the Union Jack. It isn’t organized. It has no group name. It’s just random people from around Northern Ireland.

“Imagine in the U.S.,” he said. “The stars and stripes have been flying over their town hall for 100 years and the town council decides to take the stars and stripes down and only fly it during statutory days. Now I can just imagine what would happen in America.”

To Dickson, the unionists feel very British despite deep Irish brogues that are no different than their nationalists’ counterparts. The Northern Irish Protestants fought in World War II and while many Northern Irish Catholics also did, the Republic of Ireland remained neutral.

They say the nationalists’ desire for a united Ireland is a shot at the unionists’ Britishness.

“The cultural war against the unionist people has continued, and it has continued up to this day,” Dickson said. “I think most people just want to get along with their lives. There’s always a minority who keep things going. Like Sinn Fein want to continue this cultural war. It’s why they’re using the Irish language. There’s nothing wrong with the Irish language but they’re using the Irish language as a weapon and beat the unionists.

“The vast majority of people here aren’t worrying about who’s a Catholic and who’s a Protestant. They go into the shops and go into the cafes and when the flag was flying there, I don’t think the vast majority of people noticed there was a flag there. So they made an issue of the flag when there wasn’t an issue.”

I asked what what would happen to Northern Ireland if it became part of Ireland.

“The greatest fear if there was a united Ireland tomorrow, we’d cease to be British,” he said. “We’d be British in our hearts still but constitutionally no. There are too many minorities in the world. We only have to be beaten once. We don’t intend to be beaten again.

“We’re the Ulster Scots. We’re the people who made the United States of America. We’re the frontiersmen of the United States of America. If it wasn’t for the Ulster Scots, you’d be singing ‘God Save the Queen.’”

I started my New Year’s Eve early. I made a beeline that afternoon to Shankill Road, which had no establishment O’Byrne felt safe to enter. He even lowered his voice as he talked near the Bayardo memorial.

It brought up a question I’ve had all my life about Belfast: How does one tell Catholics from Protestants? They look the same. They talk the same. They have the same blood.

It’s all about the pub and what street it’s on.

“The bars are regular bars,” O’Byrne said. “If you walk in and you’re not one of them, they’ll spot you like that. They’ll just start talking to you: What are you doing here, lad?”

Then came the key questions: What school do you go to? With Belfast’s educational segregation, you might as well hand over a birth certificate. What’s your name? Patrick? James? Conor? Catholic. William? Harry? Jack? Protestant.

As John, I could pass for both. I’m also a quarter Irish, a quarter English, a quarter Scottish and a quarter Swiss. I’m 100 percent WASP. I’m as ethnically boring as Wonder bread. I was raised Presbyterian in Eugene, Oregon, and went to Sunday school until my father bristled at it eating away at NFL games on TV. I’ve never been back.

So I had no fear walking into The Stadium Bar, a dive bar on Shankill featuring a pool table, two poker machines and cheap pints of Guinness at 3.50 pounds (about $4.35). I sat on a barstool and ordered a Guinness. My accent, as American as a Chevrolet commercial, made the question about where I’m from superfluous.

“Oregon but I live in Rome now,” I said.

“What brings you here?” said the friendly female bartender.

“What better place to spend New Year’s Eve than Belfast?” I said. “Plus I’ve never been here before.”

Next to me was a diminutive old man who talked to me for 10 minutes in a brogue so thick I didn’t understand a single word he said. I may as well have been in a bar in Bhutan. Next to him sat a much younger man who’d only give his name as Jim and wasn’t shy when I said I write a travel blog and pulled out my tape recorder. He told me about the riots he’d been in, about growing up hating people the same as himself.

I asked what’s the worst thing he ever saw. He thought for a moment. The man on the other side of him said, “His mother was blown up.”

Jim interjected, “No, my ma’s still living. My grandfather was blown up. In the Four Stop Inn. He was one of the first in the Troubles in 1971. I was 8.”

“Your grandfather was blown up?” I said. “You had to think about that as the worst? You’re not bitter?”

“I wasn’t bitter,” he said. “I just couldn’t understand what was going on. You live with it. Then you hate each other because you’re told by other people, This is the way you have to be. You were just brought up like that your whole life.”

Jim bought me a beer and I asked, “But how do you get over your bitterness? I’d still like to see some ex-bosses under a bus.”

“Because they’re the same as us,” he said. “They lost people the same way we lost people.”

I went next door to a pub O’Byrne warned me about. The Northern Ireland Supporters Club is a watering hole base for fans of the Northern Ireland soccer team. The Union Jack as well as the flags of Scotland and Northern Ireland fly over the front door. Inside are framed jerseys of a Northern Ireland side that has made the World Cup three times, the last in 1986. It even made the quarterfinals in 1958.

It’s a beautiful bar, polished and clean. Despite being built in 1980, it looks new. I ordered a Guinness and took a seat next to a table of five. I was introduced to Mark Neill, 48, a Belfast cab driver for 25 years who now runs a taxi tour of the Troubles areas called Black Taxi Tours (www.niblacktaxitours.com). Like the tour O’Byrne gave me, Neill’s is neutral. He said he shows both sides. But it’s clear on what side he sits.

“There was a lot of negativity in the Protestant community as if the Catholic community was always being downtrodden,” he said. “It was never the case. They view themselves as second-class citizens and Protestants as first class. But when you look back to history, we’ll see ourselves always as third-class citizens. We’re all third class, Protestants and Catholics.

“But politicians made the divide, that one was better than the other. That was never the case.”

Like all Northern Irish, he’s seen his share of horror. He’s seen people shot, seen them take their last breaths just a few streets away from where we sat.

“If you listen to the IRA over the years, they tried to justify it as a war,” he said. “The British Army didn’t hide behind planting bombs. The British Army was right there in uniform. The IRA was raising a terror campaign. They were a counter offensive. A lot of the Protestant counter measures were because of attacks on their homes.”

I asked the million-dollar question: How do you feel about the Catholics here feeling Britain took over Ireland and they want their country back?

“Protestants came here 400 years ago as this part of Ireland was sparsely populated,” he said. “We came and made it our home. We started building roads. We started building towns. This became the more developed part of Ireland. They feel they came and built it. They populated it. They made it their home. They’re not going back.”

Despite all he’s seen, all he’s read, Neill said he’d have no problem if my friend walked in — as long as he didn’t promote the IRA. It has been 20 years since the Troubles ended. Northern Ireland is more prosperous economically. Visitors, like me and Marina, are discovering it.

I asked him through all this if he’s still bitter.

“No,” he said. “Before, growing up in these areas I wouldn’t have any interaction with anyone on the other side of the wall. Now I work with Catholics. I wouldn’t feel safe on Falls Road but we work together and it stays at work.

“I just see people for what they are. Those people are just like me. I realize we’re all the same. We’ve all had the same social problems. We all live on the same streets. We all work together. One man’s loss is no worse than mine; my loss is no worse than his.”

I later joined O’Byrne and his family for an early New Year’s Eve celebration. We laughed. We drank. We toasted. We drank some more. I went into 2019 thinking that Northern Ireland could teach a lot to the world, including me. I remain bitter at people for a lot less. No one ever blew up my grandfather. I was never denied employment because of my roots. Still, I have two ex-bosses I’ll never speak to again. I could never share a beer with a Trump supporter. No way.

I wish I came here during the Troubles, to feel and see true hatred from people who live across the streets from each other. But better late than never and Northern Ireland has become a safe haven with a haunting history. The people are sharing equality, jobs, lives and pints of Guinness, if not pubs and schools.

Maybe they all realize what I always have: Spilling Guinness is better than spilling blood.

Next: Belfast is a new tourist hotbed.

January 7, 2019 @ 8:38 am

Amazing article John – all your articles provoke a great deal of thought. Arm chair travel has never been so great!

January 7, 2019 @ 10:46 am

Thanks, Yvonne. That means a lot coming from you. Hope to find new places to go in the world before Trump blows it up.

January 6, 2021 @ 7:32 am

Thank you for this! One of the few articles that does our country justice