Belgian chocolate: Private tasting in Belgium a sweet introduction to greatest chocolate in the world

GHENT, Belgium – I firmly believe Belgium has more chocolate shops than Ireland has pubs and the U.S. has McDonalds. How many grains of rice are there in China? Belgium might have that many pralines.

Walking around Belgian streets is like a junkie walking around Southeast Asian opium fields. Who isn’t addicted to chocolate? I am. It’s almost everyone’s favorite food. And visiting Belgium is my sweet tooth Shangri-la. You can have France and its sauces and the U.S. and its barbecue. Hell, take Italy and its pasta.

I’ll take Belgium and its assortment of galetjes.

So imagine my delight two weeks ago when I attended a private chocolate tasting at one of the most exclusive chocolate shops in Ghent. I’d been to Belgium numerous times on magazine assignments and for pleasure. The only thing more pleasurable than standing in a chocolate shop surrounded by piles of Belgian chocolate in every shape, form and flavor is eating them.

I’ve done countless wine tastings in Italy. This was my first chocolate tasting. It was held at Chocolade Ambassade, a tiny shop in a 16th century building one block off the pretty River Leie. Unlike other chocolate shops dotting Ghent’s historical center, this one had very few chocolates on display.

“We focus on quality rather than quantity,” co-owner Dorien Jaenen said. “We really take the time to tell people to find the chocolate that fits their taste.”

Chocolade Ambassade, which opened four years ago, has sampled chocolate from 200 chocolate shops, the vast majority from some of Belgium’s 2,000 chocolate stores. What I was about to try was the creme dela cream filling of Belgian chocolate.

Belgian chocolate history

Chocolate symbolizes Belgium as much as its beer and cute, canal-covered cities. It first arrived from Mesoamerica (today’s Mexico and Central America) in 1635 when Belgium was under Spanish rule. It was a food for the elite and hot chocolate was their elixir. During its colonial period, Belgium shipped cocoa en masse from its Belgian Congo and by the 1900s chocolate became affordable to the masses.

After Belgian law started regulating chocolate in 1894, Belgium chocolate skyrocketed in 1912 when it invented the praline. That’s the rich, gooey filing of a hundred varieties inside a hard chocolate coating. Belgium began exporting in the 1960s and in 2007 the European Union introduced a voluntary quality standard to which 90 percent of Belgian chocolate companies adhere.

If you have tasted Belgian chocolate and tell yourself you’ll never eat a Hershey bar again, that’s why: standards, ingredients, pride. The formula works. According to the industry publication Confectionery Production, Belgium produces 584,000 tons of bulk chocolate and cocoa-based products every year, generating annual revenue of €5.5 billion.

Dorien took me to a basic back room and told me the story of the praline. Around 1900 a Brussels pharmacist named Jean Neuhaus wanted to remove some of the bitterness of his medicine by dipping his pills into chocolate. Suddenly, taking medicine at his pharmacy became very popular.

Then in 1912 his grandson had an idea. Why not remove the pill from the chocolate and replace it with yummy fillings? The classic praline recipe remains today.

The tastings

Dorien would spend two hours plying me with chocolates, explanations and food pairings. The first was from V-Chocolatier in Kortrijk started in 1933 and is so artisanal, they have almost no machines in their workshop. Everything is made by hand.

It was a galetje, two round pieces of hard chocolate with a soft filling inside, like a little chocolate cookie. The butter cream filling inside two hard handmade pieces of milk chocolate was absolutely decadent. It was so good, I sucked on it to let the chocolate goodness take its time oozing down my throat.

Belgian chocolate’s secret

I learned there’s a big difference between artisan chocolate and industrial chocolate. Belgium has between 300-500 (depending on criteria) artisanal chocolate companies. About 20-30 follow the formula known as “bean to bar.” That means they buy cacao beans and do all the roasting and grinding themselves. The others buy industrial chocolate and turn that into their own artisan chocolates.

Hardly any Belgian chocolate companies use the evil cheap ingredient many industrial companies in the U.S. use: palm oil. European law allows chocolate to contain up to 5 percent palm oil but Belgian companies rarely use it. Look at the fine print on any American piece of chocolate and you’ll usually read “palm oil.”

The key is in the roasting. Beans to bar are roasted at 30 celsius (86 Fahrenheit), about half the temperature used by industrial companies.

“One hundred percent cacao roasted is very good,” Dorien said. “It’s good for blood circulation.”

Belgium’s other secret is grinding the beans. Dorien said Belgian companies grind the beans to 18-20 microns, a measuring unit one-thousandth of a millimeter, as compared to 33 in the U.S.

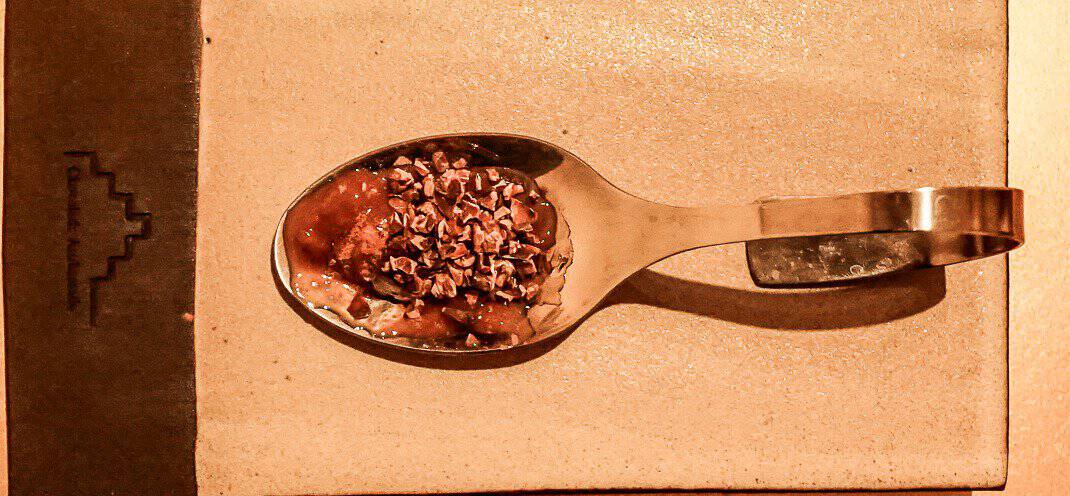

The end result was on a plastic tray in front of me. Dorien cut up some chocolate bits, called “nibs.” One was a bean-to-bar chocolate that was named the best chocolate in Europe a few years ago and made from a rare cacao variety from Peru. The other was industrial chocolate roasted at a higher temperature. I tried a handful of each. The prize chocolate had a richer, sweeter taste, one that lingered on my tongue. The other was boring, drier, kind of like eating a candy bar left over from the last Halloween.

My second sampling was from Callebaut, the biggest manufacturer in Belgium. It’s made with citric acid.

.Say what?

Yes, citric acid. It changes the fermentation and the color to an odd but inviting purple-maroon. Called “ruby chocolate,” it has a late taste of berries, kind of like a fine wine.

The third sample was from Legast Artisan, started by a husband and wife team. A Belgian named Thibaut Legast went to Colombia to learn more about making chocolate and met his wife, Patricia Forero, who was working with cocoa.

Later, Dorien made what I thought were food pairings based on a lost bet: dark chocolate with ketchup (actually, the bitterness of ketchup accents the sweetness of the chocolate), dark truffle with fried onions (not bad) and a bonbon with raspberries, black pepper, rose and balsamic vinegar topped with sea salt (an antipasto at my next balcony aperitivo in Rome.)

Price problems ahead

Unfortunately, Belgian chocolate has more swoons than just taste. Climate change crippled the last cacao crop (cacao is the name of the nut before it is roasted into cocoa) and the industry is bracing for price increases. The price of cocoa in Ghana and the Ivory Coast, which produce two-thirds of the world’s cocoa, went from $2,500 a metric ton to $11,000 last month. After bouncing around, it settled Thursday at just under $8,700.

It hadn’t been above $4,200 since the 1970s.

In an email, Dorien wrote that some bean-to-bar chocolate companies said they are spending three times their normal price for cocoa and customers will start seeing more expensive chocolate by fall.

Fortunately, I stocked up. By the time I left Belgium, I bought a box of galetjes from Chocolade Ambassade; a box of mixed dark chocolates from Leonides, one of Belgium’s biggest names; and a large assortment from Corne’ Port-Royal, started in 1932.

Next blog: My week in chocolate rehab,

If you are thinking of going …

How to get there: Trains leave about every hour from Brussels Airport to Ghent. The hour-long journey cost €18.80 one way.

Where to stay: Erasmus Hotel, Poel 25, Ghent, 32-09-224-2195, www.erasmushotel.be, info@erasmushotel.be. Great location just five minutes from the bustling Korenlei area of the Leie. Hotel is only about 20 years old but in a charming 16th century building with big rooms and a huge garden out back. I paid €244.40 for two nights, including an excellent buffet breakfast.

Where to try: Chocolade Ambassade, Kraanlei 3, 32-456-70-2736, https://chocoladeambassade.com/experience-chocolate/, chocoladeambassade@gmail.com, 11 a.m.-6 p.m. Friday-Tuesday, two-hour private tasting €79 per person.

Where to eat: ‘t Vosken, St-Baafsplein 19, 32-09-225-7361, https://www.tvosken.be/enm, Brasserie@tvosken.be, 9 a.m.-11 p.m. Beautiful location between St-Baafsplein and the towering 91-meter Belfort belfry. ‘t Vosken, Flemish for “The Fox,” has been around 134 years and is so picky about Belgium’s famed mussels it only sells them when they’re in season from the end of June through September. I had a fabulous thick chicken soup full of vegetables called Gentse Waterzooi. I paid €56.50 for two of us.

When to go: Spring. Flowers along the river are in full bloom and it’s the driest period. Our three days were in the high 50s to mid-60s with just an occasional drizzle. Avoid November and December when average low is 38 and each month gets 13 days of rain. July and August are relatively mild with average highs in mid-70s but it’s very crowded.

For more information: Visit Ghent, St-Veerleplein 5, 32-09-266-5660, www.visit.gent.be, 10 a.m.-5 p.m.