Calabria: Italy’s poorest region rich in so many other ways

TROPEA, Italy – Mark Twain, an intrepid traveler and writer of note, once wrote, “Travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry and narrow-mindedness.” It’s why I never criticize a country until I’ve been there first. (Sorry, folks. I loved Saudi Arabia. The people aren’t the government.) I never judge a foreign dish unless I’ve tasted it. (Egypt’s water buffalo brains sandwich is really pretty good.) I won’t scoff at a custom unless it hurts people. (A woman in Malaysia told me Hindu couples learn to love each other in arranged marriages.)

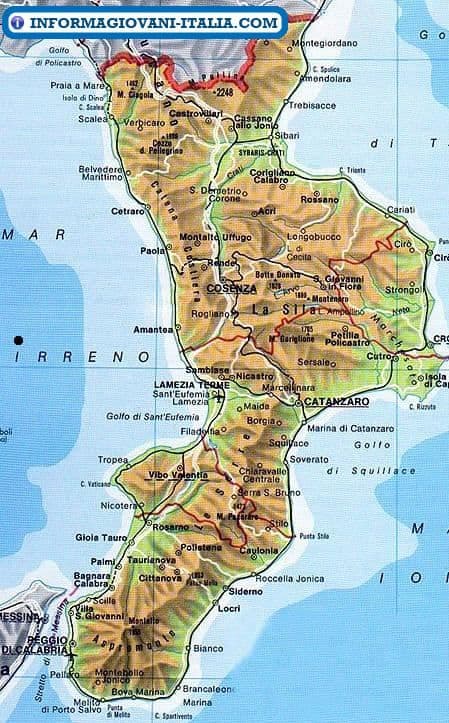

I took this attitude into the Fiat 500 I rented for a two-day drive around Calabria. This region is Italy’s paddling board. It is the toe of Italy’s boot, appropriate in that Italians kick it around a lot. It’s considered the most backward, most underdeveloped and least industrialized region in the country.

I had images of abandoned factories, squalid plains, filthy beggars and scraggly animals. I found nothing close. I found gorgeous coastline, lush national parks, cute villages and one of the coolest beach towns I’ve seen in Europe. Oh, and how do you like your octopus?

I came to Calabria for two reasons: One, for a picturesque locale to knock out some chapters in my pending book about an expat’s life in Rome; two, scratch off one of the two remaining Italian regions I hadn’t visited. (Val d’Aosta? You’re next.)

While writing on my spa’s balcony in Tropea, I kept staring out at the Tyrrhenian Sea, so blue it reminded me how far south I was. After four days of writing, I had to explore a region Italians call “an industrial graveyard.”

Calabria numbers

My research uncovered some true depressing nuggets. In 2021, Calabria had Italy’s highest unemployment rate at 19.3 percent, the lowest median income at €16,300 compared to the national average of €22,540 and the highest illiteracy rate of ages 65 and over at 19.3 percent. Every piece of material I read on Calabria included the ‘Ndrangheta, Calabria’s notorious mafia organization which has become the most ferocious in Italy.

But I don’t do business in Calabria, particularly not drug trafficking and extortion, the ‘Ndrangheta’s main MO. I was more interested in Calabria’s 155 miles (250 kilometers) of coastline, countryside that is 42 percent mountains and its three national parks.

Calabria is squeezed between the Tyrrhenian and Ionian seas and the climate is perfect for agriculture if not industry. It has the second-highest number of organic farmers and produces one-quarter of Italy’s citrus fruit. The Tropea Onions, on which I’d already developed a nasty dependency, have the coveted PGI label of Protected Geographical Indicator.

Once I got behind the wheel and headed north up the coast, I worried more if I’d make it anywhere alive. Calabria’s back roads looked like the Allied Forces bombed them during World War II and were never repaired. I swerved around potholes like they were live animals. Roads were cracked down the middle of lanes.

Its freeway, the A2 autostrada which connects the capital of Reggio Calabria at the toe’s tip with Salerno in Campania, wasn’t completed until 2016, 20 years after it started.

But when I wasn’t praying to a god I wanted to believe in, I looked left and saw a sea as turquoise as the south seas. I passed through quaint villages with nice trattorias offering outdoor seating. People strolled the grounds. Lycra-clad cyclists pedaled up the highway.

Pizzo

My first stop is the closest thing Calabria has to a tourist trap. But the Chiesetta di Piedigrotta is worth seeing, if for no other reason than to take a coffee overlooking the sea. It’s in the town of Pizzo, about 25 miles (40 kilometers) north of Tropea.

The Piedigrotta is a cave carved into the tufa rock wall and filled with stone statues depicting religious scenes. According to legend, a vicious storm endangered a ship off this coast in the mid-17th century. The Neapolitan sailors, fearing for their lives, went into the captain’s cabin where he kept a painting of the Madonna of Piedigrotta, the protector of fishermen and sailors. The sailors prayed and vowed that if they survived the storm, they’d build a chapel and dedicate it to her.

The ship sank but the sailors swam to shore. Keeping their vow, they built a small chapel in the rock. Whatever the truth is, in 1880, local artist Angelo Barone expanded the cave and carved statues of saints and Jesus. In 1917, his son spent 40 years working on the cave. After vandals damaged it to almost rubble, Angelo’s nephew, Giorgio, came from Canada at the end of the 1960s and restored it to its present condition.

I walked in and saw too many statues to count. They depicted nativity scenes, a holy mass, angels resting on lions. Cast in a yellow glow, it felt eerie and holy at the same time. The turquoise water and perfect swath of sand outside its entrance made the whole scene surreal.

I climbed back up to the street and ordered an espresso at the aptly named bar, Bella Vista, with a beautiful view of the sea. Inside, owner Rocco Burgisano was telling me how he returned to his hometown of Pizzo after years cruising the world working as the hotel maintenance manager for Royal Caribbean Cruises. I told him how Calabria surprised me, that the Calabresi seem awfully happy for being the poorest region in Italy.

“We love our families,” he said in perfect English. “Not that you don’t. But we care about our family no matter what age the kids are. Everybody’s looking after each other. It’s not like, for example, in the North. You’re 18 years old and you’re told to go to work or get out of the house. The same in America. Here your kids can stay at home until their 30s or 40s. They remain always kids.”

“So is Calabria poor?” I asked.

“It is poor. You can not tell. We say poverty but everybody has two cars, four mobiles and whatever scooter. Everybody has everything. I don’t know where this poverty comes from. Maybe from the state. Maybe it’s black work.”

That brought up the subject I advise people never to do and I did anyway. Don’t ask Italians about the mafia. It’s like asking Russians if they drink vodka. It’s a tired stereotype. They don’t find it insulting. It’s just silly. However, the ‘Ndrangheta (pronounced in-DRAWN-get-ta) has been in the national news lately.

In one of the most high-profile mafia arrests in months, police in late April arrested Pasquale Bonavota. after five years on the run. Then 100 suspected members of the ‘Ndrangheta were arrested in 10 countries and police seized €25 million. Last month police arrested 61 suspected members on raids in seven regions around Italy.

This is massive news. In the last 30 years, the ‘Ndrangheta has replaced Sicily’s Cosa Nostra and Campania’s Camorra as the most powerful mafia in Italy. The ‘Ndrangheta is an organization of families that have sovereignty over their zones. It began in the 1860s by Sicilian outlaws banished from their island by the Italian government. Due to Calabria’s lack of strong regional government, they managed to flourish and grow.

It’s believed it operates in 50 countries with 400 gangs and 60,000 affiliates, most of them in Calabria. It generates an estimated €53 billion a year.

Its laundry list of charges in these latest arrests include drug trafficking, kidnapping, fraud, infiltration of government and extorting local farmers. That doesn’t include murder although it’s reported that 15 have been killed in the last two years. That includes Antonella Lopardo, 49, who on May 2 was riddled with 18 bullets from an AK-47 and 14 from 9mm. They were actually after her husband who escaped.

A strong arm in the process is Nicola Gratteri, a prosecutor in the town of Catanzaro. In May, the newspaper Il Fatto Quotidiano reported that a foreign secret service had tipped off authorities that the ‘Ndrangheta plan to “blow up” Gratteri.

Until then he has become somewhat of a local hero.

“Now the ‘Ndrangheta is getting smashed by Gratteri,” Rocco said. “The arrests, there are hundreds and hundreds. They say now we’ll reach thousands of arrests. He’s on top of everything which is good. We’re cleaning up a little bit here.”

I asked him what’s the biggest problem a poor region like Calabria has.

“I don’t know what problems we can have once we have ‘Ndrangheta here,” he said.

Rocco is happy to be back in Calabria. The world is beautiful to see but he never saw anything he loved more than his home. After a week here, I can see why he’s not ready to set sail again.

“It’s beautiful, Calabria,” he said. “We have places we don’t even know, really.”

I went in search of a place few outside Calabria know.

Parco Nazionale di Sila

Back in the car, I continued north along the coast, curving around the Gulf di Sant’Eufemia and cut inland. The road wove up through thick forests high into the trees. I passed beautiful green pastures that could pass for golf course fairways. Yellow wildflowers were everywhere.

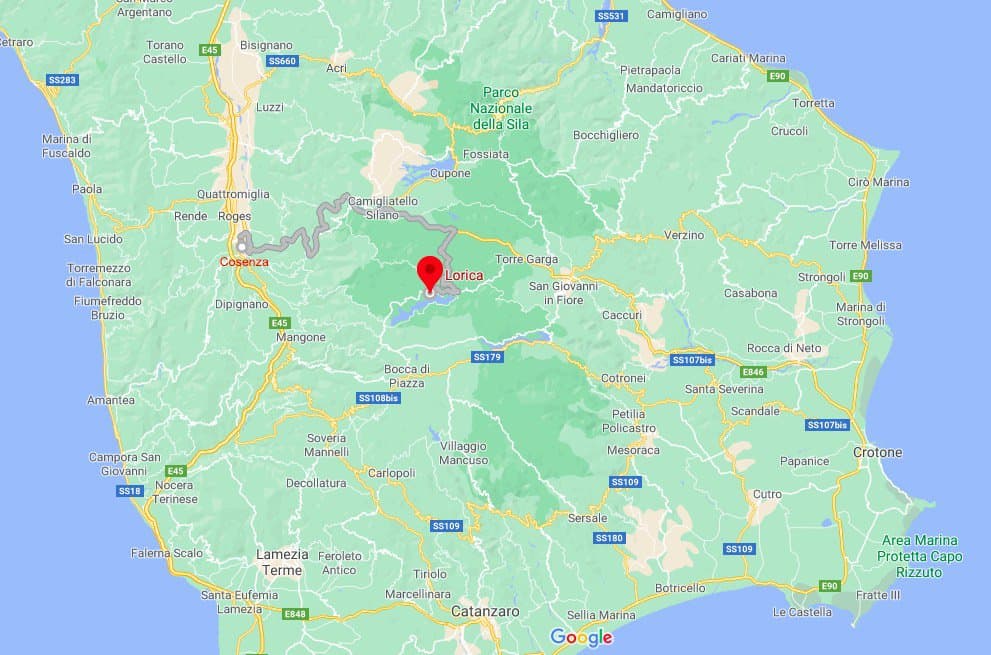

Parco Nazionale di Sila, a popular destination for Calabrians to escape the searing summer heat, is part of the southern stretch of the Apennines mountain range. Established only in 1997, La Sila covers 50 square miles (130 square kilometers) and half its mountains reach almost 5,000 feet.

Not that I saw any of them. When I reached Lago Cecita, the rain that had been threatened all week but never appeared made up for it all in one dump. I could barely see out the window on the thankfully empty road as I reached the village of Lorica.

On the edge of the lake, Lorica had the trappings of a ghost town. Two healthy-looking but perturbed, soaking-wet dogs ran down the road looking for shelter. I looked even more desperate trying to find any place open to eat. Running out of hope and wondering if I packed a protein bar, I saw a sign simply reading “Trattoria” with an arrow pointing up a gravel road.

Driving a few feet up I saw a restaurant, closed like the others. I got out to check the door. It was locked. Then I heard a voice from the story above.

“Mangi? (You want to eat?)” a man said.

“Si! Aperto? (Yes! You open?)” I said, not hiding my relief or hunger.

Aquino Mauro, the owner in blue jeans and a blue Champions brand sweatshirt, came down and opened the door. I walked into a simple but sparkling clean restaurant, as silent as a cave. He asked what I wanted to eat.

“Avete qualsiasi cosa calabrese (Do you have anything local?),” I asked.

“Si. Salsiccia e caciocavallo. (Yes. Sausage and caciocavallo cheese.)”

He brought out a big, heaping plate of steaming rigatoni with big hunks of the spicy Calabrese ‘Nduja sausage mixed with white caciocavallo cheese native to Calabria and neighboring Puglia. Afterward he brought me a big slice of frutti di bosco crostata (pie with mixed red berry filling).

Welcome to Calabria where hospitality doesn’t take weather breaks.

Through my two days in the countryside, I kept waiting to see signs of the undeveloped backward Italy I’d read about. I never did. I drove back to Tropea through the village of Taverna, typical of what I saw. It’s a quaint town of 2,900 people hugging the side of a foothill.

The streets were spotless. The homes all had red-tile roofs with brass railings on balconies spewing over with blooming flowers. Similar villages dotted the countryside beyond like hill towns without the fortified walls. Europe’s idea of poverty is a lot different than in the third world or even in the U.S.

In Calabria, I never saw one homeless person.

Scilla

The next morning I left early for another must see in Calabria. Scilla doesn’t get the national attention as Tropea, but savvy travelers put it atop the list. It’s 50 miles (80 kilometers) south of Tropea and this stretch of road goes inland up and down hills that made my ears pop. Radio stations quickly went in and out.

Villages were spread far apart. So were farms. Southern Calabria is a vast, green hilly meadow. It was a beautiful drive and Scilla capped it like popping a bottle of champagne.

The road to Scilla winds down the cliff overlooking the sea. At the last turn, I could see the long beach about a kilometer in length lined with palm trees and a few clusters of lounge chairs. It looked like a secluded beach in the Caribbean.

I parked on a side street and took a coffee at an open-air bar. Off in the distance I could see the tip of Sicily across the Strait of Messina. Few people were on the beach despite the sunny, 73-degree day. I asked the waiter if Calabria was poor. He smiled. I think he’d heard the question before.

“When you have the mountains, the sea, are you poor?” he said. “You have trees of lemons and limes. Are you poor? It’s a lie.”

Scilla is famous for something besides this lovely beach. It’s named for Scylla, a vicious monster with six dog heads that drowned sailors trying to navigate the strait. Legend has it that Scylla was a nymph who kept shooting down the advances of a young fisherman named Glauco. Heartbroken, he went to sorceress Circe and asked for help. However, Circe wanted Glauco to herself. So instead of turning Scylla’s heart toward Glauco, she turned her into a six-headed dog.

I hate it when that happens.

Scylla’s mythical lair was a rock on the other side of Ruffo Castle, the first fortification of which dates back to the 5th century B.C., and overlooks the town. Behind where Scylla once wreaked havoc is Scilla’s pretty harbor and a warren of narrow alleys going past cute gift stores, chalk-white homes with sky blue window sills and plants adorning balconies.

I took a seat at Il Pirata, one of the many seaside restaurants. Purple tablecloths covered the tables so close to the sea any wave would drench the seafood pasta. A sailboat floated by headed toward Sicily, ever so slowly on a windless, sunny day. Seagulls swirled overhead, settling on rocks to soak up the sun.

My fresh polpo (octopus) was grilled to a golden brown and adorned with soft potatoes covered in basil.

I drove back to Tropea wondering about Calabria’s bad rap. It is rural. But it hides any apparent poverty behind a positive outlook and breathtaking scenery. You don’t need money to be happy. You don’t need money to be clean. What you need is a respect for nature and a sense of regional pride.

The toe of Italy’s boot is definitely tapping to the right beat.

If you’re thinking of going …

How to get there: Trenitalia has numerous daily trains from Rome to Tropea starting at €58 one way. The 5 1/2-7 hour trip connects at Lamezia Terme. ITA Airways has three direct flights a day from Rome-Fiumicino. The 70-minute flight starts at €167 round trip and goes to Lamezia Terme, 35 miles (60 kilometers) north of Tropea. Some hotels have free airport shuttles. ITA also has three flights a day from Rome to the regional capital of Reggio Calabria on the southern tip starting at $164.

Where to stay: Hotel Tropis, Contrada Fontana Via Nuova, Tropea, 39-09-63-607-162, www.tropis.it, info@tropis.it. A four-star wellness center a 10-minute downhill walk to Centro Storico. Features a swimming pool, spa and full buffet breakfast. I paid €95 a night in May. Price jumped to €153 in June.

Piedigrotta B&B, Via Riviera Prangi 80, Pizzo, 39-09-6306-0079/39-377-08-44-792, piedigrottebnb@libero.it. Directly above Chiesetta di Piedigrotta. Jacuzzis in rooms that start at €144 for a double.

Where to eat: Il Pirata, Via Grotte 22, Scilla, 39-09-65-704-292, https://www.ubais.it/ristorante-il-pirata/, peter@ubais.it, 12:30-3 p.m., 7:30-11 p.m. Thursday-Tuesday, 9 a.m.-11 p.m. Wednesday. With tables over the sea in the fishing district of Chianalea, it has seafood pasta dishes starting at €12.

La Trattoria di Aquino Mauro, Via Cesare Curcio, Lorica, 39-09-84-533-015, noon-3:30 p.m., 7-10 p.m. Monday-Tuesday, 9 a.m.-3:30 p.m., 7-10 p.m. Wednesday-Friday, 9 a.m.-4 p.m., 7-11 p.m. Saturday-Sunday. Home-cooked Calabrese dishes on a secluded alley, a great place for lunch after exploring Sila National Park.

How to get around: Rent a car. Le Torre Motors delivered a car to my hotel in Tropea. I paid €105 for two days including insurance and not counting gas.

When to go: Avoid July and August when it’s packed and temperatures are in mid-80s. My last week in May was 72 and sunny nearly every day with lows in mid-50s. In January lows are low 40s with highs in high 50s.

For more information: Tourism Reggio Calabria, Via S. Anna 11, tr. 2, 39-09-65-362-2835/39-09-65-362-2570, https://turismo.reggiocal.it/, turismo@reggiocal.it.

ProLoco Tropea, Piazza Ercole, Tropea, 39-09-63-61475, https://www.prolocotropea.eu/, info@prolocotropea.eu, 10 a.m.-1 p.m., 6-9 p.m.

June 13, 2023 @ 1:45 pm

What a wonderful part of Italy, I knew nothing about. Love your descriptions. I could not find the towns you mention on the map, Google it is.

June 13, 2023 @ 4:14 pm

Thanks, Virginia. Scilla is on the first map just above Reggio Calabria. Lorica is on the Sila map below it. I couldn’t find one that included Taverna.

September 13, 2023 @ 5:44 pm

Would you live in Scilla?

September 25, 2023 @ 8:41 pm

I could, yes. There aren’t many places in Italy I couldn’t live.

June 13, 2023 @ 3:00 pm

Great stuff John! Love these hidden gems….thank you

June 13, 2023 @ 4:11 pm

Thanks, Mike. I can’t wait to return.

September 26, 2023 @ 12:43 pm

Hi John, greetings from Australia. What a wonderful series of articles on Calabria, thank you. As you know, I love Tropea, but can’t wait to visit Scilla and other places on the Calabrian coast after reading about your travels. And also to have a few more beers with you in Rome some day soon…regards, Giuseppe

September 27, 2023 @ 9:30 am

Thanks, Giuseppe. Marina and I want to spend a long weekend in Scilla. Give me a head’s up when you return to Italy. How’s everything in Australia? You can Whatsapp me: 39-347-898-3667.

John

June 13, 2023 @ 6:14 pm

Great write up John! Thanks for shedding light on such interesting region of Italy.

June 13, 2023 @ 9:58 pm

Thanks, Paul. I was lucky to go when I did. I wouldn’t want to try it this summer.

June 14, 2023 @ 5:21 am

I enjoy your reports from Italy. If you’re still there, next up in Calabria should be East, hugging the Ionian Sea. Check out Catanzaro Lido…it’s a Cool beach town (or suburb of Catanzaro) along the the Ionia Sea. It’s a Real Cool place. Then drive East to Le Castella….and then further east along the Ionian Sea to Capo Colonna and the nearby sanctuary of Santa Maria di Capo Colonna. Wow! Then East to Crotone…Enjoy!

June 15, 2023 @ 10:41 am

Thanks for the tips, Perry. I almost went to Gerace after Schilla but didn’t think I’d have enough time to explore. I will on my next visit and visit your recommendations.

June 14, 2023 @ 12:48 pm

Loved your article John. It brought back many fond memories of our two weeks of travel in Calabria in 2019. We visited coastal, valley and mountain towns and enjoyed all of them! Calabria has a lot to offer to visitors in the way of its history, its culture, its food and its people. The young driver we hired to take us from town to town made us feel like we were a part of his family, so much so that he insisted we had to return the following year to be his guests and to attend his wedding. You have to love and admire the Calabrians for the way they live their lives, despite the fact they are considered to be among the poorest regions of Italy. Calabria is rich in so many other ways!

June 15, 2023 @ 10:40 am

Thanks, Constantine. Calabria is also off the beaten path once you get out of Tropea. I want to return to Scilla for a very long weekend in September.

June 14, 2023 @ 9:00 pm

I have an Italian friend here(now living in Mexico) whose last name is Calabria. Nice to see where his ancestors came from. I’ll forward him this lovely tribute to his homeland. Thanks.

June 15, 2023 @ 10:39 am

Thanks. Tell me what he thinks. Is he from Calabria or just his ancestors?

June 15, 2023 @ 10:20 am

Thank you for sharing a positive perspective of Calabria. It is beautiful. The people are warm and caring. No one thinks they’re “poor.” No one thinks they’re missing anything outside of Calabria. There are many beautiful coastal and mountain villages. There are large supermarkets, mall, stores, crafts, fantastic restaurants … in beautiful towns. Many fantastic farm to table restaurants. From other expats, some retired American RNs , I heard good reports on healthcare.

Oh. Now I miss Calabria. Will go in September.

June 15, 2023 @ 10:38 am

I got the impression that the locals were tired of the stereotype. Honest, I saw no signs of anything poor. Thanks for the kind comments.

November 30, 2023 @ 9:37 pm

John. I Thank you for your great story. About Calabria well done

My friend.

Trust statement.♂️

December 15, 2023 @ 7:09 pm

Thanks, Joseph. I will make a return trip this spring.

June 13, 2024 @ 9:56 pm

the region is not well connected (twisty tiny roads looked bombed). there is almoast no flat surface. only hills and mountains making it very hard to bring industry or any kind of bussines there. even if italy had the resources to invest, there is no place where you coukd put a big town. not to mention a gas pipe, water and so on. in august they turn of the water for most of the day. not even electricity is a given. in sommer the power goes of almoast everyday in places like tropea. sometimes for 5 minutes sometimes for hours. They are “condemned” to this faith first of all because of the terrain. like every place hard to reach by truck prices go up so overall calabria is more expensive than rest of italy except for local products that are normally priced. in tropea the place you talked about a pastabdish is around 14 euros and a beer around 4-5 euros. during the day the whole place looks like falling appart as you rarely see a house with no broken windows or walls falling or holes in the walls as big as your head. i give you that the water there is just incredible. a very clear turquoise, part of it because there is not really sand but stones in water and on the beaches. so it looks good but when you try to go in the water it s not without pain. at sunset when the light becomes dim the whole ruined look starts to have a charm around city center tropea but leave the center and you get really depressed. people are very nice and friendly and the views from the coast looking the the sea are incredible. you can see the stromboli vulcano in front of you while on the beach of tropea. some island far on the left and huge mountains on the right. in this regard the view is really unique.

June 17, 2024 @ 2:27 pm

Interesting perspective. Maybe being an American who has traveled throughout the third world, I was surprised at how little poverty I did see. Interesting points about the terrain being a hindrance to public services. What’s Rome’s excuse?