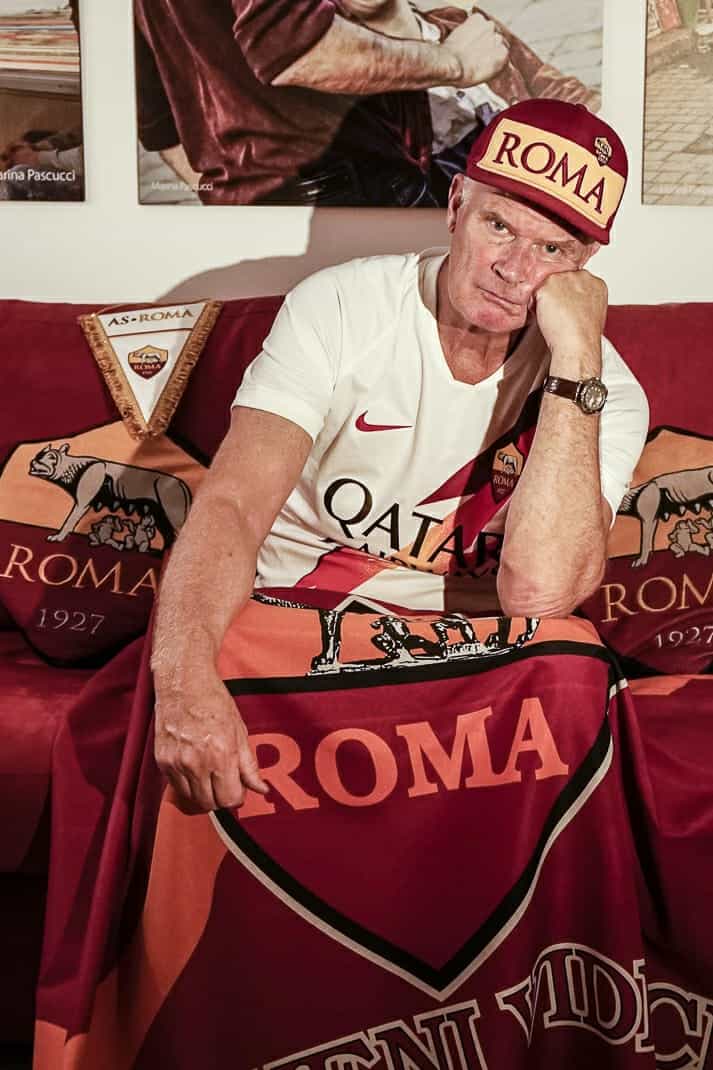

European soccer season begins with frustration for me and AS Roma fans

AS Roma’s season begins Saturday, and I’m approaching it with the resignation usually reserved for my tax return or tomato sauce. I’m always disappointed. Enduring Roma’s season is worse than an Internet date. At least with an Internet date you have hope. With AS Roma, hope is just something that gets broken quickly, like a plate glass window in the back of a net with a leaky defense which Roma very well could have.

This will be my eighth straight AS Roma season and 10th overall while living in Rome. In the past seven seasons since retiring here in January 2014, we have finished (starting last season) fifth, sixth, third, second, third, second and second.

For the last nine seasons, we, as well as the rest of Italy’s Serie A, have looked up at the King Kong of Italian soccer, straddling one of the Dolomites and swatting opponents like so many paper airplanes.

Rooting for Juventus in Italy is like rooting for Amazon. It has won 36 Serie A titles and in two of our three second-place finishes we finished 17 points back. In 2016-17 we finished four behind, primarily due to winning our last four and Juventus winning only two of its last five to make it close.

This is my lot in life. Since transforming from a sports writer to a sports fan upon retirement to Rome, I find myself doomed for an eternity looking up at others. I enter every year hoping we finish second, third or fourth and nab one of four Champions League spots for the following season. No one should dream of finishing fourth. Dreams shouldn’t have ceilings. My ceiling gets more suffocating every year.

European soccer’s imbalance

But I am not alone. Fans from Seville to Berlin face the same dilemma. It’s what separates American sports fans from European soccer fans. The NFL opened last weekend and any team not in Ohio thinks it has a shot. And it does. History proves it. But for us in Europe, our lots in life are stamped in the standings at the end of every season.

Look at European soccer’s big four: Besides Juventus going for a record 10th straight Serie A title, Bayern Munich seeks its ninth straight in Germany’s Bundesliga, Paris-St. Germain goes for its eighth in nine in France’s Ligue 1 and in Spain’s La Liga, Barcelona and Real Madrid have won 15 of the last 16. Only in England, where the Premiership has had four different champions in the last five years, is there much mystery.

It’s not just the traditional power nations. Celtic has also made the Scottish League moot, winning the last nine. It and crosstown-rival Rangers have won every title since 1984-85. Porto or Benfica have won every Primeira Liga in Portugal since 2001-02. Red Star Belgrade and crosstown rival Partizan have won every Serbian SuperLiga since 1997-98.

U.S. pro sports balance sheet

Is this really sport? As an American, I’ve struggled with the Groundhog Day atmosphere of European soccer. Compare it to the U.S:

- The NFL has had eight different Super Bowl champions in the last 10 years and 13 in the last 20.

- Major League Baseball has had a different World Series champion the last six years, 12 in the last 20 and 16 in the last 30.

- The NBA has had seven different champions in the last 10 years and nine in the last 20.

- The NHL has had six different Stanley Cup champions in the last 10 years, 13 in the last 20 and 16 in the last 30.

- MLS has had seven winners of the MLS Cup in the last 10 years and 12 in the last 20.

America is the land of opportunity? It sure is in pro sports. Compared to the U.S., most European soccer teams are like Oliver Twist asking for more gruel.

“The entire ruling class of management in European football is pretty old fashioned,” said Paddy Agnew, World Soccer magazine’s Rome-based correspondent for the last 30 years. “The idea of changing anything is difficult.”

U.S. sports and European soccer have two massive differences that explain much of the discrepancy. U.S. sports have a draft. The worst teams in each sport get the first picks of the best amateur players although MLS teams also are developing fledgling academies. European teams sign whomever they want at whatever age they want and place them in their youth academy. Juventus’ Cristiano Ronaldo signed with Sporting CP in Portugal at 12. Paris-St. Germain’s Kylian Mbappe signed with Monaco at 15. Bayern Munich’s Manuel Neuer started with his hometown Schalke at 15. They are then developed, featured and sold to the richest clubs, allowing the small clubs to keep afloat financially and the rich clubs to keep winning.

The hierarchy remains in place.

Role of TV money

An even bigger difference may be TV money. Take the NFL, which has the richest broadcasting rights of any sports league in the world at $5 billion a year. Every NFL team receives $255 million before the first ticket is sold.

Serie A’s contracts are worth 973 million euros ($1.15 billion), fifth highest in Europe. Through a complicated formula including overseas rights and on-field results, Juventus last season received 100 million euros ($118 million), and Brescia, from its town of 200,000 about 50 miles east of Milan, received 40.5 million euros ($48 million).

Welcome to the classic juxtaposition of political philosophies. In the United States, socialism is equated in many circles, including many NFL fan bases, with communism. Yet the NFL’s system is classic socialist equality. Even Karl Marx would approve. In Europe, where socialist systems creep into many societies ranging from education to public health, its soccer teams are classic capitalists.

And like the white jersey of Real Madrid, it’s not going to change.

“In countries like Spain and Italy it’s very difficult to do things that Juventus and Real Madrid, Barcelona, don’t want to do,” Agnew said. “It’s a huge control of power.”

What also motivates the power clubs to keep the status quo is European soccer’s relegation system. Unlike the NFL where the Detroit Lions can perform worse than the city’s auto industry for decades and never lose its franchise, the bottom three clubs in each European league drop to the second division every year. The top three in the second division get promoted to the first. It’s as if the Detroit Tigers, Baltimore Orioles and Miami Marlins last year dropped to Triple A and were replaced by Round Rock, Las Vegas and Columbus.

No major soccer club would agree to equal distribution of TV money and risk more equal competition. Not fair? Tell that to Spezia, from the town of La Spezia (pop. 93,000) on the Ligurian Sea, which will play in Serie A for the first time in its 114-year history. In Italy, in Spain, in Slovakia, every village team has a shot at the big leagues.

“You can have equality of opportunity but that means you won’t have equality of outcome,” said Stefan Szymanski, an Englishman and professor of sports management at the University of Michigan and who has written numerous books on sports economics, particularly in soccer. “Or you can have equality of outcome but you won’t have equality of opportunity. And you can’t mix these two. These are either or choices.

“The reason for that is what gives the equality of opportunity in soccer is promotion and relegation. Promotion and relegation can only really work if the big clubs are not required to engage in any redistribution of wealth. Redistribution of wealth means the big clubs become as susceptible to relegation as the small clubs.”

It helps explain why the Premiership, with its 1.67 billion pounds ($2.15 billion) broadcasting rights, has had more balance in recent years. This past season, each club received 31.8 million pounds for domestic TV rights, 5 million pounds from commercial revenue and 43.2 million pounds from overseas TV rights with bonuses depending on how high they finish. Liverpool made 174.6 million pounds, less than twice last-place Norwich City’s 94.5 million pounds.

Solutions anyone?

What can be done? Well, nothing. UEFA, the governing body of European soccer, installed Financial Fair Play in 2009. If any team goes over a certain amount, it must pay a fine, similar to Major League Baseball’s luxury tax. But rich soccer club owners treat it like a parking ticket.

“I’m a well-known critic of the system,” Szymanski said. “It’s not about fairness at all. It’s largely about trying to restrict the capacity of wealthy individuals to come in from outside the system and buy success as Chelsea and Manchester City did. They actually helped to promote more competition against these established dominant teams.

“One way to think about it is, how do you challenge more dominant teams? Largely the way that’s going to happen is the injection of capital.”

Why else could Leicester City come out of nowhere in 2015-16 to win its first Premiership crown? In 2010, the club was bought by a Thai-led Consortium fronted by King Power Group and its chairman, Vichai Srivaddhanaprabha, who, before his death two years ago, was worth nearly $5 billion.

“Soccernomics”

I don’t read sports books much. I read too much about sports during the day. But between my two Rome stints I read “Soccernomics,” which Szymansky co-wrote with British journalist Simon Kuper in 2009. It is the bible to explain the economics of a sport that, despite leagues with all the drama of Grade B sitcoms, is the most popular sport in the world.

You Americans? Forget the NFL. Last season’s Super Bowl had a TV audience of 102 million. The 2018 World Cup final had an audience of 1.1 billion. Manchester City claims to have 700 million fans worldwide.

How many jerseys do the Dallas Cowboys sell in Malaysia?

“Soccernomics” also explains why fans tolerate such a system. It’s Szymanski’s village mentality. Spezia knows it can’t win Serie A, but if it can pull an upset on one of the Milan or Rome teams or sober up Juventus for a half, its season is made.

“It’s true, absolutely true,” Agnew said. “Even for a big club like Roma or Lazio, half the time the main event of the year is beating the other team in the derby. In their heart of hearts, most Roma and Lazio fans are going to start off saying, ‘Well, we’re not going to win the title. Let’s at least beat Lazio. Let’s at least beat Roma.’

“For small provincial teams it’s fantastic. Years ago I was at the game in Pisa when Pisa beat Inter. They’ve been talking about it ever since. It was about 35 years ago.”

Szymanski grew up in Wimbledon where its occasional first-division club was boring and he latched onto his mother’s hometown team in Scunthorpe, in Northern England about 50 miles from the soccer hotbed of Leeds.

“It’s a small team that usually plays in the third or fourth tier,” Szymanski said. “They’ve never been in the top tier. A few times they’ve been in the second tier. They’re really an insignificant little club but always every season I’m hoping, Maybe this year they’re going to get promoted. And it’s all going to change.

“I could spend a lifetime with that hope even though it’s never happened in my lifetime.”

Roma hopes

What are my hopes for Roma this season? About the same as Pope Francis stopping by my place for a beer. The Houston-based Friedkin Group has taken over ownership from fellow American James Pallotta who tired of going nowhere on his 1.5-billion euro stadium plan and said “Fuck it!” Our set-piece specialist and solid defender, Aleksandar Kolarov, was sold to Inter Milan. Roma can’t agree to terms with Manchester United to keep our best defender, Chris Smalling, who starred on loan for Roma last season. We couldn’t get a bag of balls for our inconsistent goalkeeper, Pau Lopez.

Nicolo Zaniolo, our best young star and already a national team player at 21, blew out his second knee in two years and is likely out for the season. And if Arkadiusz Milik, a Polish national team player, reluctantly agrees to leave Napoli for Roma, we’ll sell our best striker who’s tied for fourth all-time on the club in goals, Edin Dzeko.

To Juventus.

September 16, 2020 @ 10:32 am

An American sports fan can never really prepare themselves for their first experience at an Italian soccer game. The only time I’ve EVER felt unsafe in Rome was at the stadium. https://rickzullo.com/soccer-in-italy/

September 17, 2020 @ 1:25 am

Great article!

September 27, 2020 @ 3:32 pm

Hi,

All perfect about the review on the situation of As Roma. One question: do you no longer speak of your passion for the Trastevere team, does the team still exist?

All the best,

Anton

November 26, 2020 @ 2:37 am

Anton: I just saw your comment. Sorry this is late. I had a falling out with Trastevere two seasons ago and have only been back once.