Derby Day in Rome: a vicious rivalry that can still bring opposites together

(Editor’s note: I was planning on posting this Monday but yesterday was meant for remembering Kobe Bryant and not a relatively meaningless soccer game in Rome.Riposa in pace, Kobe.)

It was a terrific idea to celebrate a birthday. Alessandro Castellani, my best Italian friend in Rome and veteran sportswriter, had gathered seven of his male friends to an arranged dinner. We were all huge soccer fans who loved to watch, read and, most of all, talk about soccer. Wives and girlfriends were left at home. It was eight men at a table with a lot of wine and a lot of antipasti and a lot of pasta. What made this dinner was the makeup of the guests.

It was four fans of AS Roma and four of Lazio, two of the bitterest rivals in world soccer.

The history of this rivalry goes back to 1927, when AS Roma formed from the confluence of three teams, much to the annoyance of Lazio which formed in 1900. For the last 90-plus years the rivalry has divided this city of 2.8 million. It has defined people, neighborhoods, political parties.

The games have been marked by vicious words, distasteful signs, some violence and one death.

As a Roma fanatic since 2002, I have occasionally replaced war, animal abuse and cancer with Lazio on my hate list. They were the vile racists, the fascists, the uncouth outliers who helped give Italian soccer — and Italy itself — a racist reputation.

Since moving to Rome a second time in 2014, my stance has softened. Beating Lazio has become more of a goal than an obsession. It’s no longer personal. It’s like two enemy soldiers who find themselves trapped in a cave and, forced to get to know each other, slowly see good in each other.

Alessandro’s dinner captured it beautifully. And it came at the perfect time. It was 11 days before the derby, the rivalry game called theDerby della Capitale:Sunday’s massive Roma-Lazio game.

We met at the new restaurant in Trastevere Stadium, a purely neutral site as it’s home to Rome’s 111-year-old Serie D team, ASD Trastevere. Modest in both atmosphere and price, the restaurant had only us and one couple with two annoying, screaming kids running around.

The eight of us had so much in common. In fact, having opposing colors was about the only thing we didn’t have in common. The whole stereotype of Lazio fans, known asLaziali,are all fascists from the suburbs, didn’t even reach the edge of our table.

I talked to one Laziiale who didn’t want his name mentioned but went on a Hendersonesque tangent on his hatred for Donald Trump and Matteo Silvini. He is Italy’s version of Trump whom Salvini admires and, in his brief time in power here for 15 months until September, steered Italy so far right it brought back memories of the man who inspired one of my favorite Trump nicknames: Mango Mussolini.

Also holding court was Andrea Colacione, a prominent local TV soccer commentator and Lazio fan who went on a rampage against Claudio Lotito, Lazio’s myopic owner who’s as unpopular with Lazio fans as Roma owner James Palotta is with ours.

We wound up closing the place down past midnight, walked out into the cold, dark stadium, exchanged one last laugh, shook hands, man hugged and wished each other good luck on Jan. 26.

But to understand the heavy symbolism of this benign evening, one must understand the meaning of this rivalry. Alabama-Auburn? You aren’t even close.

***

Who’s behind it all? The man who promised Italy glory and gave it misery instead.

Benito Mussolini.

When he took power in the 1920s, he wanted a unified Rome club to challenge the Northern Italian soccer powers. Backed by the fascist general Giorgio Vaccaro, Lazio’s vice-president, Lazio wanted nothing to do with other local clubs. So in 1927 in a small brick building in the working-class neighborhood of Testaccio, my home from 2014-18 south of the historical center, the clubs of Roman FC, Alba-Audace and Fortitudo-Pro Roma formed A.S. Roma.

Nearly three decades earlier, Lazio, taken for the name of the region, was formed in Prati, the Vatican’s neighborhood, and played in Parioli, in the north and to this day the ritziest ‘hood in Rome. Thus, Lazio was considered the wealthy, classy team. Roma was the poor, working-class club. It is why the Lazio ultras are in the north end of Olympic Stadium and Roma’s are in the south.

The two teams co-existed peacefully for decades with Lazio tasting its first success in 1958 when it won its first of seven Italian Cups. But then came 30 years of heavens and hells. From 1961-86 Lazio was relegated to Serie B four times and had to win a playoff in 1986 to escape Serie C. In the middle of all this, it won its first of two Serie A titles, called thescudetto, in 1974.

But as politics in Italy changed, so did the fans. The 1970s were tumultuous with fascists and communists squaring off in Parliament, in bars, in the streets. In fact, on my first trip to Italy in 1978, fascists blew up the train tracks on my ride from Rome to Milan. (As a side note, it had nothing to do with me today being just to the left of Gandhi.) Many fans were identified politically by their soccer affiliation: Laziali were right wing;; Romanisti were left wing.

The good-natured office ribbing began getting heated. In a derby in 1979, Lazio fans held up a banner reading,“Rocca bavoso, i morto non resuscitano.(Slobbering Rocca, the dead are not resurrected).” It was an uncouth shot at Francesco Rocca, Roma’s star young player whose career had just been cut down by a terrible knee injury.

A Roma fan in Curva Sud responded by firing a flare across Olympic Stadium into Curva Nord. It punctured the eye and into the brain of Vincenzo Paparelli, killing the 33-year-old mechanic in front of his wife. Years later during a derby, Roma fans sang,“Tu Laziali, testa di cazzo, in Curva Nord spareremo un altro razzo.(Ugly Lazio, dickhead, in Curva Nord we’ll shoot another rocket.)”

Roma went on to win its second of three Serie A titles in 1984. Its third title came in the 2000-01 season. On Dec. 17, 2000, Lazio’s Paolo Negro scored an own goal in Roma’s 1-0 victory. Negro, who played for Lazio from 1993-2005 and helped Lazio win the scudetto the season before, is still taunted to this day.

In the 2001-02 season, when I lived in Rome the first time, Roma wallopped Lazio 5-1, with Vincenzo Montella scoring four goals and Roma legend Francesco Totti assisting on two of them and scoring another. Montella celebrated each goal by running around the pitch with his arms stretched out, reflecting his nickname “Aeroplano.”The next day I remember seeing news clips of smiling Roma fans riding their motor scooters with their arms stretched out in glorious imitation.

On March 21, 2004, four minutes into the second half of a scoreless tie, fans of both teams stormed the pitch and ordered the game stopped. Fans at the top of the stadium had peered down and saw a young boy covered in a white tarp. Word spread that an overzealous policeman, who are abundant on derby day, had killed the child.

The game stopped and a full-scale riot unfolded outside the stadium. It was one of the few times Roma and Lazio fans agreed on something. However, the child was not dead. In fact, he wasn’t hurt. Police were protecting him from the fumes of flares but the riot resulted in 18 arrests and 170 injured.

Then came a series of one upmanships: In 2013 Lazio beat Roma 1-0 in the first Rome derby Italian Cup final. On Jan. 15, 2015, Totti scored twice in his 40th derby and celebrated with an in-your-face-Lazio selfie with fans in Curva Sud. On Dec. 4, 2016, Roma won its fourth straight over Lazio. The game was marred by a brawl when Lazio’s Davilo Cataldi grabbed Roma’s Kevin Strootman after the first goal and Strootman responded by throwing water in Cataldi’s face. Also, Lazio’s Senad Lulic received a 20-day ban for racist remarks in a post-game interview about Antonio Rudiger, Roma’s black player from Germany, saying, “Two years ago he was selling socks and belts in Stuttgart, now he acts like he’s a phenomenon.”

As the Roma-Lazio rivalry grew more heated, so did Lazio’s fascist side. A number of Laziali had swastikas and fascist symbols in their stadium banners. One banner during the 1998-99 derby read, “Auschwitz is your town, the ovens are your houses.” In 2017 Lazio fans put anti-Semitic stickers of Anne Frank in a Roma jersey and anti-Semitic graffiti at the stadium.

What being Jewish has to do with Roma, I can’t answer. As a club, Roma is no more Jewish than Lazio. Rome’s Jewish Ghetto is in the center of the city, Roma territory, but it long ago transformed into a tourist destination and Lazio claims the whole city anyway.

Just for kicks, after Lazio won 3-1 on April 30, 2017, Lazio hung dummies in Roma jerseys along the sidewalk near the Colosseum with a banner reading, “A warning without offense … sleep with the lights on!”

As a knee-jerk, liberal, left-wing Democrat who lists among the fringe benefits of living in Rome as never having to meet racist Trump supporters, these actions fried my keyboard. Then again, the journalist in me kept seeking the other side of the coin. Roma’s recent history isn’t clean. To wit:

- On May 12, 2013, Roma fans yelled monkey chants at AC Milan’s Mario Balotelli, Italian born to Ghanian parents and a member of the Italian national team.

- On Oct. 20, 2017, Roma fans did the same to Chelsea’s Antonio Rudiger, who left Roma the previous summer, partially because of the club’s failed attempts at curbing racist behavior.

- On Oct. 20, 2019, Roma fans made monkey chants at Sampdoria midfielder Ronaldo Vieira from Guinea-Bissau.

- In September, Roma banned for life a fan who made racist remarks on Instagram about Juan Jesus, Roma’s occasionally struggling defender from Brazil.

After all this, who am I to criticize Laziali for fascism?

Romans for Roma

The ultras of both clubs hate the media, primarily for having the audacity to print their actions. So I decided to sit down with men from opposite sides of our dinner table that one night.

I met Alessandro Castellani and his brother Paolo at Sora Pia, about a 150-year-old trattoria across the street from Alessandro’s apartment in Cornelia, a busy neighborhood in northwest Rome. It’s not so ironic that Sora Pia, not far from where Fortitudo-Pro Roma played, often fed Roma teams in the 1930s. It now feeds its supporters, mainly us.

Alessandro has been a sportswriter for 42 years and has been at ANSA since 1988. He has covered Roma and some Lazio on equal terms and has forgotten more about soccer in Rome than I’ll ever learn.

His brother Paolo may be the top Roma historian alive. He wrote two books, “La Maglia Che Ci Unisce (The Shirt That Unites us),” a history of A.S. roma, and “55 Secondi,” about Roma’s loss to Liverpool in the 1984 European Cup final. Unlike most Romans, they didn’t adopt their affiliation from their father.

“Our father was a Lazio fan,” Alessandro said. “He lived in Flaminio very close to the stadium. He told me he used to see lots of Lazio players, including (Silvio) Piola who was his idol and he became a Lazio fan. Players were available to people. Not like now.”

However, the two boys had an uncle from Perugia who became a Roma fan while serving here for a year with the Army. He used to take Alessandro to the stadium for Roma games. In 1969, the entire Roma team and coach visited Alessandro’s grade school. He has been attached ever since.

I told him about a 2014 British documentary about the derby. It called it “one of the most violent in the world.” Alessandro chuckled.

“There is no violence in the derby,” he said. “Never. In the ‘70s was the only time I saw violence. No, I saw violence twice: That time when Paparelli was killed and a few years ago at the derby they were fighting the police.”

He has also seen Lazio’s fascist side up close and personal. The club’s rap has attracted Europe’s growing neo-Nazi population. During Lazio’s Europa League match on Nov. 8 with Celtic of Glasgow, a group of East European fascists, all dressed in black, attended the game. They threateningly approached Castellani.

“It was four against me,” he said. “They said, ‘You are a Celtic fan?’ No, I’m from Brazil. I started speaking Portuguese. I was lucky they believed me.”

I asked what he thought of Lazio’s fascist image.

“It’s a small group,” he said. “I don’t think it’s a big group. Lotito, I don’t like very much. But did you read in the newspaper? Lazio can’t take this anymore.”

True. Last week, Lotito announced he would use video cameras with face recognition capabilities to identify fans who make racist gestures during games. Each fan would be fined 50,000 euros.

I asked Alessandro if he hated Lazio. No. He hates Juventus, Serie A’s 500-pound gorilla which is again in first place and aiming for its unprecedented ninth straight title. He hated Lazio once. With three games left in the 2010 season, Roma was two points behind first-place Inter Milan. Inter played Lazio, going nowhere that season, at Olympic Stadium. Lazio fans desperately wanted Roma not to finish first.

“I was there for work,” he said. “In all my career I’ve never seen a game like that where you can feel, you can see, one team doing everything possible to lose. Lazio made Inter win.”

Inter did, 2-0, and won the scudetto by two points.

A left-wing Laziali

Franco, who didn’t want his last name used, is a tour guide and met me at Il Colonnato, a hopping, coffee bar and cafeteria just outside the Vatican walls. His father came from Le Marche, a region on the Adriatic, and moved to Rome where he befriended kids who took him to Lazio games. As an adult, he settled in the Vigna Clara neighborhood above Ponte Milvio, a Lazio stronghold near the stadium. This is where Franco grew up.

Like his fellow Laziale I met at Alessandro’s dinner, Franco is politically liberal, belying the prejudgment I had about Lazio fans years before. Over coffee before he led a tour group through Rome, we got along famously. I asked how he’d describe the rivalry.

“The rivalry of Lazio-Roma is maybe interpreted in 100 ways,” he said. “Usually in the past it was characterized by happiness, jokes and fun. The world changed, not in a very good way, and the rivalry became in a few cases characterized by anger and even violence.”

We talked about the changes in society and how it affected Italian soccer.

“Ninety percent of the ultras in Italy are close to the extreme right,” he said. “Even the Roma fans. At the beginning they were close to the division of left-right. Now everything changed. Perugia. Atalanta. Ancona. Livorno, almost all the others are extremely on the right side.”

He talked about fights he’s seen between teams’ own ultras where there exists a division between left and right. For example, Franco’s grandfather was a partizan who fought against Italy’s fascists during World War II. Franco’s father was closely aligned to the communist way of life.

“So it’s kind of crazy I love Lazio and I think Lazio from the beginning of the day until I go to sleep,” Franco said. “Because I am a romantic lover so even now when I go to the stadium, I listen to people sing songs and remember the fascism and they sing things that have nothing to do with football or the Lazio story.

“It’s very, very hard to live in this situation.”

He said 90 percent of the Lazio fans love Lazio “for the history, the colors and don’t have any kind of relation with politics with the right.” However, 10 percent is a lot. If Roma or Lazio have 2,000 away supporters and 200 make monkey sounds, that is a large representation of a club. Any fan base accused of racist chants, no matter how many are chanting, deserves its racist reputation.

The game would be in two days. I asked him if he had any advice for me.

“Don’t show you are for Lazio or Roma,” he said. “Sometimes going to the stadium, you go near a group of 20-30 people from the other side and they can attack you, hurt you, while 50,000 people are just happy to go see the game.

“But if you don’t know how to go there, where to walk, it’s better to avoid it.”

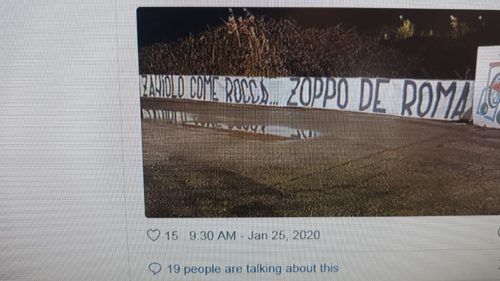

On Friday, two days before the game, Lazio fans struck again. They placed a huge banner on Roma’s training ground reading,“ZANIOLO COME ROCCA … ZOPPO DE ROMA.(ZANIOLO IS LIKE ROCCA … LAME OF ROMA).” It’s a cheap shot at Nicolo Zaniolo, Roma’s star 20-year-old striker and one of the best young players in Europe who blew out his knee Jan. 12.

Accompanying the banner was a giant drawing of a wheelchair.

The next day, thousands of Roma fans came to Roma’s practice and chanted support, lit flairs and held up banners like,“VINCENTE PER ZANIOLO(WIN FOR ZANIOLO).”

No violence in the derby? We’ll see the next day.

Coverage huge

On game day, Corriere dello Sport, the Rome-based national sports daily, went beyond its usual soccer hysteria. It had 11 pages previewing the game PLUS a 24-page pullout special section on the rivalry’s history. Rome’s new slogan: It’s the city where sportswriters do not sleep.

Loren De Feo, who fell in love with Roma in 1999 while discovering her Italian roots and lived here from 2013-18, was meeting me at a bus stop in Largo Argentina. It seemed like an appropriate place to meet on derby day. The bus stop isn’t far from where Julius Caesars was murdered. Loren flew in from Zurich, where she moved to teach, just for the game and, like me, wrapped herself in a Roma scarf on a mild day in the 50s.

Getting to the stadium on derby day is a major undertaking not unlike the Roman army marching to the Adriatic. The bus wouldn’t arrive for 30 minutes and we could not hail a vacant cab from the main drag along the river, Lungotevere. We met two Austrian tourists who were in the same dilemma. One couldn’t reach Uber; I called a taxi twice and got hung up on. We finally reversed into Centro Storico and stood in line at a taxi stand.

The cab driver was a Romanista who went on a diatribe against Salvini whom I mildly argued wasn’t as bad as Trump. Salvini didn’t cut taxes for the rich, I said. He doesn’t believe in guns. He didn’t pull Italy from the Paris Accord. “No!” the driver said. “It’s much easier to buy guns now. He doesn’t believe in Global Warming. He just didn’t have the power to do anything.” As we drove to a game between two teams defined by right and left, it was a small victory for the left that day when Salvini’s right-wing Lega party lost its election in Emilia-Romagna, a traditional leftist stronghold.

I left the cab, telling the driver,“Forza Roma!(Go Roma!”) and joined a mob walking to the front gate. Curiously, it was all Roma red and yellow. I didn’t see a sky blue scarf or sweatshirt in sight. I knew we were in good company when we joined the scrum at security and, with marijuana smoke filling the air, a huge chorus broke out.

“LAZIO MERDA!

LAZIO MERDA!

LAZIO MERDA!

LA FOGNA DI QUESTA CITTA!”

(LAZIO SHIT!

LAZIO SHIT!

LAZIO SHIT!

THE SEWER OF THIS CITY!)

I asked for a translation and fans began chuckling. I high fived a female fan and two or three asked us where we were from. Romanisti love fans from other countries. They’re jealous of Juventus’ international appeal and want to expand Roma’s footprint.

One 30ish man tapped me on the shoulder and said, in halting English, “We appreciate your kind words for Roma.”

We entered the stadium 45 minutes before gametime and couldn’t see a vacant seat anywhere in the 50-year-old grounds. We squeezed into our third row seats and marveled at the pageantry. Besides the usual flag waving and songs — some of which were actually clean — the choreography in such a chaotic setting was remarkable.

At one point, Curva Sud held up signs that formed the beloved interlocking ASR logo that Roma used from 1997-2013. We stared at Curva Nord to see the Laziali hold up lights that formed the words “FORZA LAZIO.” Moments later they held up cards that depicted “The Creation of Adam,” the iconic part of Michelangelo’s fresco in the Sistine Chapel showing Adam and God almost touching fingers. It was all set in a sky blue background. It meant Lazio was created before Roma ever existed. It was a reach but beautiful nevertheless.

“I’m surprised how organized they are, these fascist bastards,” Loren said.

Roma fans greeted the remarkable artwork with their ubiquitous,“LAZIO! LAZIO! VAFFANCULO! LAZIO! LAZIO! VAFFANCULO!(LAZIO! LAZIO! GO FUCK YOURSELF! LAZIO! LAZIO! GO FUCK YOURSELF!)” Quickly returning from Curva Nord came,“ROMA! ROMA! VAFFANCULO! ROMA! ROMA! VAFFANCULO!”

No. Cal-Stanford this is not.

On many derby days, the game’s importance is secondary to the tension in the stadium. Sunday was different. The game was huge. Lazio (14 wins, 3 ties, 2 losses) stood in third place with 45, seven points ahead of Rome (11-5-4), which was tied with Atalanta (11-5-5) for the fourth and final Champions League spot for next year. Juventus (51) and Inter Milan (47) stood first-second. Lazio and Roma had tied 1-1 Sept. 1.

Roma stumbled in with not only Zaniolo hurt, but rising star midfielder Amadou Diawara was out with a knee injury, one of seven starters who’ve been hurt this season. Being the basic pessimist that I am, I told my local bar that morning,“Siamo fottuti.(We’re fucked.)”

We weren’t. We controlled the action through the first half. In the 26th minute Edin Dzeko, Bosnia’s national star and Roma’s leading scorer, out-leaped two Lazio players and goalie Thomas Strakosha to head the ball from about 20 meters out for a 1-0 lead and his 99th career goal for Roma.

The stadium erupted. I lived in Denver 23 years and never heard the Broncos’ stadium as loud as that moment. I tweeted that I want to visit Bosnia.

Roma continued applying pressure. Lazio’s Ciro Immobile, Serie A’s leading scorer with 23 goals, barely touched the ball. Roma looked headed to an epic victory in the 93-year history of the rivalry.

Then, at the 34-minute mark, all the air shot out of Curva Sud, like a child’s popped balloon. Roma’s 25-year-old Spanish goalkeeper, Pau Lopez, spectacular all season, casually went up to grab a harmless, botched header falling lazily into his arms. His attempt at fisting it away nearly whiffed and defender Chris Smalling couldn’t clear it, leaving it right in front of Lazio’s Francesco Acerbi to kick it through.

The second half, Roma continued to dominate but Stakosha, Albania’s national goalkeeper, was magnificent. He stopped Dzeko from close range and then again. Immobile was never a factor and Lopez was rarely needed. Roma wound up with a 66-percent possession advantage and out-shot Lazio, 22-6.

But we walked out deflated with a 1-1 tie that hurt Roma as much as it helped Lazio, seeking its first Champions League group stage in 12 years. On our short walk to the tram stop, we again didn’t see a single Lazio fan. This chaotic city, which isn’t organized enough to pick up garbage once a week, somehow manages to keep two viciously loyal fan bases away from each other as they enter and leave a stadium.

I returned home with more disappointment than hatred, more pessimism than bitterness. I’ve made many Laziali friends in Rome and I made more this month. It is a good, healthy rivalry with two thriving teams backed by passionate fan bases. I hope to continue my relationships with my Laziali friends and I wish them luck the rest of the season. And in that spirit I’d like to leave them with the following sincere message, from the bottom of my red-and-yellow heart:

LAZIO! LAZIO! VAFFANCULO! LAZIO! LAZIO! VAFFANCULO!