Dupuytren: My surgical dive into private Italian healthcare

Ever tried washing dishes with one hand? It’s ridiculous. I squeeze soap on a plate and move it around the sink with a sponge like a cat playing with his food. I squeeze the sponge inside my milk foamer hoping I can still make a decent cappuccino the next morning.

Showering? I’m rubbing myself down with one hand while the other arm, heavily wrapped in two plastic shopping bags, is stuck over the shower like I’m hailing a cab. Brushing my teeth with my left hand feels as foreign and difficult as riding a unicycle. I predict teeth will start falling out any day now.

As a writer, this is like walking with one leg. The words appear on my computer screen followed by a Red Sea of lines indicating typos. My right pinkie is rendered useless under a heavy, thick bandage. I can’t reach the P, asterisk, question mark, dash or return keys. I’m a classically trained typist who typed 92 words a minute in eighth grade and I’m hunting and pecking with random fingers like a keyboard is a new invention.

All the while I have occasional pain shooting up my hand to my fingertips, just to remind me that an ailment that affects 8 percent of the world’s population is not just a pain in the hand. It’s a pain in the ass.

I have Dupuytren.

The disease

It’s a disease that shortens and thickens the connective tissue in the palm. Over time, a finger slowly and steadily bends to a 90-degree angle. It will not straighten without corrective surgery. If it goes untreated, a second and possibly third finger will also bend. Soon your hand starts resembling a rake.

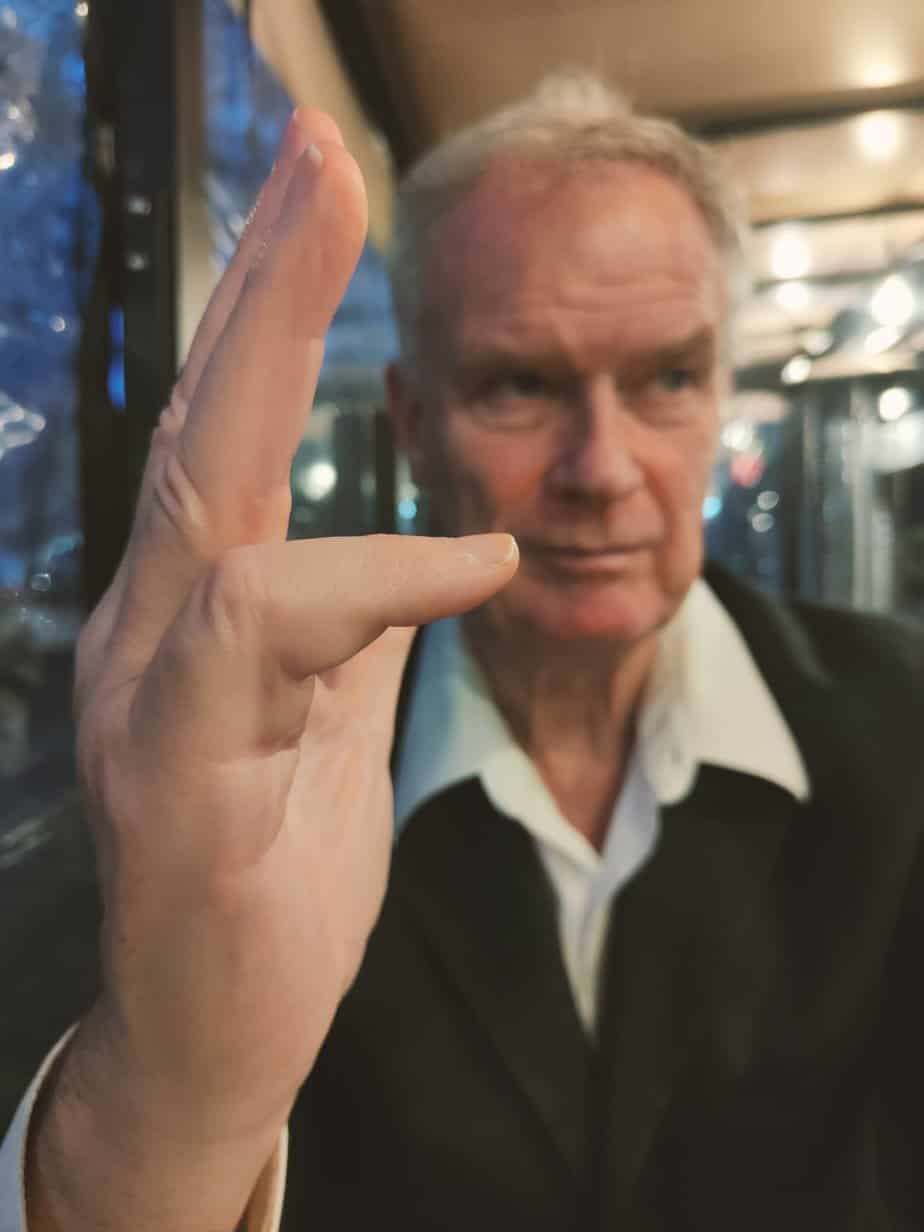

My right pinkie eventually became a hook. It didn’t hurt. It also didn’t bend. I could still lift weights. It curled conveniently around bars. But shaking hands was awkward and my writing had more typos than a teen’s Whatsapp messages.

I first noticed it two years ago and had it checked. I went to Salute Nuovo Regina Margherita, a huge public clinic in the Trastevere neighborhood, just down the hill from my home. The woman took one look at my right pinkie and nodded her head.

“Dupuytren,” she said.

What? I’d never heard that word. It didn’t sound Italian.

“Du-puy-TREN,” she repeated.

She took my left hand and rubbed my palm. She said I had it there, too. I needed surgery or my right ring finger would join the pinkie in a 90-degree salute, followed by my left hand. How could this happen? What did I do to cause this?

Nothing she said. It’s mostly hereditary.

I called my older sister in Eugene, Oregon. Turns out she had it as well. So did our dad. Then it hit me. I do remember his pinkie being constantly bent at a weird angle. I had no idea it was Dupuytren.

Also I had no idea he had seven operations and they never cured it.

That’s when I got nervous. My sister said Dupuytren surgery has made great advancements. It cured hers and she didn’t even have any pain afterward. I’ll be fine.

Living in Rome, I knew surgery would be free. Yes, even non-Italian citizens reap the benefits of Italy’s superb public healthcare. Physical ailments here have soft landing pads. I put myself down for surgery and the hospital said they’d write me when they had a surgery date. I waited.

And waited. And waited.

Italy has the second-ranked healthcare performance in the world, according to the World Health Organization, but among the negatives of socialized healthcare is the wait period for non-emergency surgery can last forever. It took me nine months to get laser surgery on my eye.

This took longer.

The time dilemma

It became problematic. Dupuytren surgery is quick. You’re in and out in a day. However, the rehab is five-six weeks. Don’t plan on anything for a month and a half. I’m a travel writer. I’m never in one place for a month and a half.

I didn’t travel anywhere without cancellation insurance but this July I must attend two events: My 50th high school reunion in Eugene and my nephew’s wedding outside San Luis Obispo, California, the next day. If I didn’t want to fist bump people with a bandaged hand or drive a rental car one-handed, I needed a five-week window after surgery.

Last November I returned to Regina Margherita and told them my dilemma. The doctor nodded, scribbled my July dates and said they’d try to get me in no later than the first week in June. After living in Rome for 10 years, I know waiting for Italians to do anything, whether it’s scheduling surgery or a bus arriving on time, requires patience no human possesses.

Job would’ve burned Rome again long ago.

I had an option, I could have the surgery done at a private hospital. I’d have to pay but how much could that be? All medical costs in Italy are cheap, right? My family doctor recommended Giuseppe Taccardo, the top hand surgeon in Rome.

I visited him at Gemelli University Hospital, and I could tell the difference between Italian public and private healthcare. Regina Margherita is ancient, built in the 10th century. Although the current hospital opened in 1970, it looks like an ancient ruin without the historical character. Drab walls. Dark lighting. Overgrown grass in the courtyard.

Gemelli, built in 1964, is a brightly lit, 10-story mini metropolis, the second largest hospital in Italy and the largest in Rome. It has more parking than a shopping mall. I knew it would be top of the line.

The pope gets treated there.

I met Taccardo, a burly man with a friendly smile and understanding nature. He took one look at my finger and heard my schedule. He said he’d schedule the surgery for the first week in May. Five-six weeks rehab would put me in mid- to late June, plenty of time to regain my grip by my first return to the States in five years. Regina Margherita eventually called and said they’d get me in between mid-May and mid-June.

What year, they didn’t say. After all, this is Italy.

True to Taccardo’s word, I had surgery May 6. How much would it cost? He didn’t know. I wasn’t concerned. Again, this is Italy.

Dupuytren facts

In the meantime, research told me 5 percent of Americans contract Dupuytren and it’s three to 10 times more in European countries, particularly in Scandinavia.

The causes are unknown but case studies show the following can contribute:

- Smoking. (Never smoked.)

- Extreme alcohol abuse. (I live in Rome. The biggest social faux pas you can commit is alcohol abuse.)

- Liver disease (See above.)

- Diabetes. (Nope.)

- High cholesterol (Nah. Mine’s 180.)

- Thyroid problem (Tiny bit of inflammation)

It usually hits men after 50 and women much later. The right hand gets it before the left, and 80 percent of cases are in both. According to a study by the National Library of Medicine, the recurrence of Dupuytren is 3.5 percent. After living in Las Vegas for 10 years, I liked my odds.

The payment

I walked into Gemelli for the first surgery of my life. At 68 years of age, I’d never had a broken bone, torn knee, heart condition or major ailment. I went legally blind in my right eye six years ago and had laser surgery. I hoped Dupuytren surgery would be as painless. Despite looking straight up into a needle working on your eye, you don’t feel a thing in laser surgery. It was the same thing with Dupuytren. Nothing hurt except one place.

The wallet.

I sat down at a desk to go over the payment plan. My Belgium-based insurance company, Expat & Co. Insurance, would cover it but I had to pay out of my pocket first. I knew the average cost for Dupuytren in the den of larceny that is U.S. healthcare was about $6,000. I figured it would be, comparing past medical costs to that in the States, about $2,000-$3,000. She told me the amount.

€8,236.56. That’s nearly $9,000.

I asked her what it all includes. She went through the procedure.

When she finished I said, “What do you mean it doesn’t come with a happy ending?! For €8,200?!”

Declining to first request a lubricant, I handed over my credit card, comforting myself knowing I could use the airline miles.

In 10 years in Italy, this was the first thing I’ve seen in healthcare that was more expensive than in the U.S. Damn pope. He always drives up costs in Rome.

The surgery

While the pope gets treated on the 10th floor, I went to the fourth, a sprawling maze of waiting areas, elevators, hallways, offices and operating rooms. After getting dressed in a hospital gown and donning a mask for the first time since Italy’s Covid last lockdown ended, I got wheeled in a bed past waiting rooms full of gawking patients and family.

The last time I had anesthesia was when I had a colonoscopy in the U.S. That was a nightmare turned into a dream. They told me to count down from 10. I went “10 … 9 …….8 ……” Boom! I was awake. It was over.

I asked if they’d put me under for a Dupuytren.

“There is no need,” a nurse said.

What went to sleep was my arm. In a matter of minutes, the anesthesia turned my arm from a functioning limb to a limp piece of meat. I couldn’t feel a single finger. A great white shark could bite my forearm and I wouldn’t feel a thing.

“It feels like somebody else’s arm, doesn’t it?” said an assistant, the only one in the room who spoke English.

They put up a blanket between my eyes and arm so I couldn’t see the obviously grotesque procedure of cutting open my palm and rearranging nerves and tendons. My arm was so numb that it still felt up in the air, the last position it was in before it went under. I asked the assistant if it was in the air like I was waving at someone.

“No. It’s flat on a board.”

After an hour, the blanket came off and I saw my hand heavily bandaged. It looked like a boxer’s taped fist before he puts on his glove. The soft cast allowed four fingers to stick out with a little wiggle room. My bandaged pinkie stuck in the air but at least it was straight for the first time in two years.

The arm was still numb. I could pull my arm up with my left hand and it would flop down like a giant prosciutto roll.

They wheeled me back to the room to wait an hour for observations. But playing with my arm like it was a new toy slowly gave way to growing agony. As the anesthesia wore off, feeling started rolling up my arm until I could move my fingers.

What they felt was pain I had never experienced before. Suddenly, my hand felt like it was under the tire of a Fiat. When pain shot up through my palm, I had new appreciation for what Jesus went through.

They discharged me and I waited for Marina to pick me up at the pharmacy where I eagerly bought painkillers Tora-Dol and Tachipirina. Tachipirina? That’s for hangovers. Not hand surgery.

That night, I slept about two hours. The rest of the time I moaned like that Fiat tire was grinding my hand into the pavement.

Over the next week, as pain subsided, I learned to live one handed. The three movable middle fingers allowed me to dress myself but I drew the line with socks. They were impossible. Taccardo told me if I got the cast wet, I would never heal. Marina gave me a pile of plastic garment bags to wrap around my arm in the shower.

Slowly I adapted. I got used to stares. I only once joked after an inquiry, “You should see what happened to her.” It wasn’t funny. But trying to explain Dupuytren in Italian was an interesting language lesson.

Taccardo said I couldn’t exercise until the bandage came off. If it got wet with sweat it would be just like soaking it in the shower. So I had an extra 90 minutes every day to write basically one-handed, read and wonder why the pain kept increasing.

The checkup

I returned Tuesday to change the bandage. I stole a peek at my bare palm and a string of stitches zigzagged from near the bottom of the thumb to the bottom of my little finger. It looked like an aerial shot of a long railway. Taccardo said the pain is normal. In fact, I read the pain can last for months. Lovely.

All so I can hit the “P” key on my laptop.

When he finished I asked him if the operation was as complicated as it seemed even though it’s considered routine and takes only an hour.

“It’s very complicated,” he said. “You must cut into the palm, spread out all the nerves and tendons and cut out the aponeurosis.” That is the thin fibrous band that covers the muscle and continues into the tendons.

My new bandage is smaller. My pinkie is indeed straight. I can now exercise, at least my lower body, and I must change the bandage again next week. Overall, my hands are in good hands at Gemelli.

No wonder the popes live so long.

May 22, 2024 @ 4:14 pm

Wow. Glad it’s finally done. Now trip to USA will be more enjoyable.

May 22, 2024 @ 5:45 pm

Thanks. It’ll be more enjoyable as long as I don’t meet a Trump supporter.

May 22, 2024 @ 7:41 pm

My dutpetrens surgery here in Idaho-$26,000gor the scurgery center and $5000 to the surgeon.

May 23, 2024 @ 10:22 am

Really? $20,000? I went all through the Internet trying to find out outrageous Dupuytren costs in U.S. and kept seeing average cost of about $6,000. Your story doesn’t surprise me. How much did your insurance cover? Mine covered 199 percent.

May 23, 2024 @ 1:39 am

John Elway had Deputren’s and is advertising a drug cure for it. I’m glad you’ll be back typing. I really enjoy your work.Thanks , Bill in Denver.

May 23, 2024 @ 10:20 am

Thanks, Bill. When did Elway have it? What drug works on it? I’ve heard of no medicine that helps except surgery.

May 24, 2024 @ 5:33 am

It is an injectable drug called Xiaflex. They are advertising it regularly in the U.S.

May 23, 2024 @ 1:51 am

You might consider radiation therapy to slow or stop recontracture of your fingers. Low dose treatment of benign (non-cancerous) conditions is 80 per cent effective & increasingly available

May 23, 2024 @ 10:19 am

Never heard of radiation for Dupuytren. By the time I noticed it happening, it was already too late. I needed it reversed, not stopped.

May 23, 2024 @ 5:26 am

I’m not looking forward to mine now…thanks…. Hopefully the VA issues me some good pain killers. Hope you heal quickly John

May 23, 2024 @ 10:18 am

You have it? My doctor was very aggressive with mine. Maybe that had something to do with the pain. You may not have any. Good luck. And hope it doesn’t return. If mine does, I’ll live with it.

May 23, 2024 @ 2:18 pm

Have had it for years but being a mechanic its hard to be out of work for 6 weeks after surgery. On the other hand (pun intended) its hard working on an engine when your right hand has a hook on it….Now that I am an instructor, I can finally get it done. They do have a drug for it, an injection, but it needs to be treated in the very early stages. Cant remember the name of it.

June 17, 2024 @ 4:07 pm

I had surgery 4 weeks ago on my left little finger -a myofasciectomy which is removal of fascia plus the skin. I believe the disease is in the skin so a skin graft (from my forearm) hopefully will give a longer lasting result. Unlike John I’ve not experienced particularly bad post operative pain although it has been worse than after I had my right little finger operated on 7 years ago when I didn’t have a skin graft. Infact, I had no pain at all after that operation. It is taking much longer for the finger to heal this time because of the graft. I’m pretty well back to doing most things except driving, gripping the steering wheel would be difficult and sore. I also had a xiapex injection in my right finger 2/3 years before surgical fasciectomy; I found that a gruesome experience and the contracture came back quickly. I’ve had all my surgery at Wrightington hospital in the U.K. under Mr Hayton,a very good hand surgeon. My last op was private and by the time I finish with the hand therapists,it will have cost me just over £3000. So, looks like I’ve had a better experience than John.

June 18, 2024 @ 10:34 am

Mine was the most expensive in the world. It’s because of the hospital, they tell me. Gemelli is the second largest private hospital in Italy and serves the pope. It also serves the general population on the state healthcare plan. They provided me with the best hand surgeon in Rome and insurance paid so I’m not complaining too loudly.

May 23, 2024 @ 11:29 am

Very informative thanks John. So does it always start in the pinky finger??

May 23, 2024 @ 5:43 pm

Thanks, Robert. No. It often starts in the ring finger.

May 24, 2024 @ 10:23 am

Thanks for a very informative piece, John. Despite my Nordic heritage, I still haven’t had symptoms at age 73, and I’m hoping I won’t. But now I will know what to expect if I do.

May 27, 2024 @ 8:30 am

It sucks, John. It’s a lot more painful than I anticipated. Also, I notice the finger is still a little bent. That is more than concerning. The doc’s assistant said it might be because of the bulky bandage, which I get off tomorrow. We’ll see.

May 24, 2024 @ 4:05 pm

Thx so much for this story. Super interesting. Am happy to be living in San Sebastián now & hope to find a good Depuytrens surgeon here. My pinky looks like yours did.

May 27, 2024 @ 8:28 am

Good luck, Darlena. Be prepared. It has been three weeks since my surgery and the hand is still in pain. Also, my pinkie is still bent a little. I’m REALLY hoping it’s because of the bulky bandage. I get it removed tomorrow. Tell me how yours goes.

August 18, 2024 @ 9:54 am

Will do, scheduled for next month.

Btw, the surgery in S Sebastián with Dr Pajares (recommended surgeon) would cost only $3500).

August 19, 2024 @ 8:33 am

Good price. Believe it or not, the hospital that did my surgery is giving me a €1000 refund. I guess they overcharged me. Something to do with a miscalculation of taxes. I don’t understand it, nor will I question it. My hand is nearly 100 percent, though.

May 27, 2024 @ 6:53 pm

Diagnosed in March with Dupuytren. Left hand had bothered me for 18 months. So far, it’s only my left ring finger. Was in some pain, but altered my workout routine and feel fine. Realize that will probably change. The hand doctor was extremely nonchalant with the news. No big deal, he told me four or five times. Hope he’s right. Best of luck in your recovery, John. See you soon.

May 27, 2024 @ 9:38 pm

Thanks for the note, Dave. So you did not get surgery based on the doctor’s nonchalance? I was told if you don’t fix one finger, another will be the same. Your doctor never mentioned that? Typing became a real hassle with my pinkie useless. If my ring finger joined it, I’d be fucked. Also, my left hand is going to face the same outcome some day. Right now, I still have pain three weeks after the surgery and noticed that my pinkie is not completely straight. That bothers me more than the pain. The doctor’s assistant said it’s probably because of the big bandage on it. I hope he’s right. I see the doctor again tomorrow.

May 30, 2024 @ 1:39 am

Hope you heard a good report at the doctor, John. My Dupuytren appears to be moving slowly, for now. The hand started bothering me 18 months ago, and it’s been feeling a little better because I’m more careful about use of my left hand.

My fingers are not yet bent. I realize that could change.

May 30, 2024 @ 8:32 am

Why is the hand feeling funny? Mine never did. It just kept bending. It never hurt.

June 17, 2024 @ 3:55 pm

I had my first diagnosis in my 50’s and was told not to try any treatments until my fingers really started to bend. Since then I’ve had 4 operations on my right hand and one on my left along with some nerve damage which affects me more in cold weather. Both pinky fingers starting to bend again now. As far as I’m aware there is no cure; it keeps coming back and the NHS in the UK is way too slow so private treatment really the only option. Good luck with your recovery.

June 18, 2024 @ 10:37 am

My sister’s finger is starting to bend again after 28 years. Another contact has had no problem. Why did you have FOUR operations on the same hand? The first three didn’t work? This was quite an ordeal. They told me I have Dupuytren in my other hand but by the time that finger bends I’ll be in my 70s. I’m going to let it go. This has taken about three months out of my life that I don’t want happen again. However, my finger is almost back to normal after six weeks.

June 20, 2024 @ 7:04 pm

I had to have another op the year after the first because it started to affect my ring and middle fingers. I was ok for maybe 3 years when it started again and finally, the surgeon recommended a skin transplant from my arm to finger to try to break the chain of disease. That finger is now pretty deformed (swan neck it’s known as) and my little fingers on both hands starting to curl in again. I’m retired now so I’ll think long and hard before contemplating more surgery but when you’re working it’s very intrusive and can’t be ignored.

June 25, 2024 @ 8:06 am

Oh, God! What a nightmare. I’m sorry. Where do you live? I hope that doesn’t happen to me. My finger is almost back to straight but the nerves are not repaired. The tip has no feeling, making typing difficult still. I can’t lift weights for about two more months. Even lifting my roller bag on my recent trip was painful with my right hand. When my left pinkie begins to curl, I will not operate. You’re right. This is a major intrusion in one’s life. It’s fine now. When it goes, I’ll be in my 70s. Who cares at that point?

June 17, 2024 @ 4:24 pm

I had surgery under general anaesthetic for 2 hours on 4 June in a private day surgery hospital/clinic in South Africa. Surgeon + anaesthetist bills amounted to around R45 000 in total; I’m not sure if the clinic will bill me too. My right little finger was more severely affected than yours John. The prescribed meds (opiate + antiinflammatory + paracetamol [acetaminophen]) controlled pain adequately and I managed without them after 3rd night post-op. I have been experiencing intermittent and mostly transient aches in various parts of my finger and palm at odd times. Stitches come out tomorrow, which I am not exactly looking forward to: I took a photo last week when cast was removed and can count about 20 stitches.

June 18, 2024 @ 10:30 am

Your surgery was cheap and sounds like your meds worked better than my Tachiparina. Don’t worry about the stitches getting removed. It didn’t hurt. My surgeon was careful. But how could your finger be worse than mine? Mine was a steel hook. It wouldn’t budge. Are you doing exercises? Mine are working great. That and two physical therapy sessions have the finger at about 90 percent back to normal.Yesterday I got the bandage off and I can start swimming, which will be a good substitute for lifting weights. That is still two months away. I still have soreness in the palm and tingling in the finger but they’re improving. Good luck. Keep me posted. I’m curious.

June 18, 2024 @ 11:09 am

Thanks John. Removal of stitches went better than anticipated (I had an uncomfortable experience after dermatology surgery recently), and surgeon is happy with what he saw. I see the occupational therapist later this week when I expect to get instructed about an expanded range of exercise.

Tachiparina appears to be plain paracetamol which (in my opinion – I’m a retired pharmacist) is inadequate on its own for post-op pain for the kind of surgery you endured. I had oxycodone 5mg for 3 days plus anti-inflammatory plus paracetamol (=acetaminophen in USA).

I judged my finger as being worse than yours from your pre-op photo; my little finger was bent into an inverted U with the end segment (distal phalanx) pointing vertically down parallel to my palm. Happy to share a photo! I was unable to grip a 4kg weight 2-3 months pre-op, and by 7 days pre-op couldn’t get my finger round the bar of a 1kg weight.

June 18, 2024 @ 5:31 pm

OK. You win. Besides Tachiparina, which is best for hangovers and not post surgery, I had Tora-Dol in which I put 15 drops in some water. That worked better.

July 4, 2024 @ 8:19 pm

John, thanks for this great account of your encounter with Dupuytren.

At several points when reading it, I was not sure whether to carry on in bewilderment and scare myself to death or, just put it to one side and go off to smugly wash the dishes or/and have a shower. I did read it all and despite its very serious nature, I can’t recall having read anything so entertaining and at the same time very informative for some time. I suppose I’ve got the onset of D in my right hand, of course. I guess it’s been present for about four or five years now. Slowly becoming more prominent but nothing that anybody notices, or if they did, are too polite to mention it, and does not affect my lifestyle in any way, yet. I play a bit of trumpet for fun, and was concerned that you say the second and third fingers tend to go after the pinkie has gone. As you may know, we need all those three fingers to operate our valves on the trumpet. My fall-back plan is the trombone – but don’t mention this to my wife please.

Thank you so much for putting this together for us.

Best wishes, Peter

England, UK

Btw, I particularly liked your “Nothing hurt except one place. The wallet.” and, pleased to note that you’re not a fan of Donald. I’m not going to go there, here.

July 6, 2024 @ 8:28 am

Thanks for the kind note, Peter. One thing I’ve learned since that blog is the earlier you operate on Dupuytren, the easier the rehab. Mine has been hard. Lots of pain. Slow recovery. Today marks two months since the operation and I am finally able to use my right hand in the shower and washing dishes. And I have two more months of rehab before I can start lifting weights with my arms. My strength in my right hand is nil. My doctor and physical therapist said if you operate early, it’s much easier. My doctor said my advanced stage made the operation more complicated. My sister did hers relatively early. She had no pain the next day although her rehab was two months. The problem is it really didn’t handicap my life much. With your trumpet, it likely has an impact. If I were you I’d get the operation. My ring finger is safe now. However, my other hand is going to eventually have the same problem. It’s normal now. When it starts to curl I’ll likely be in my 70s. At that point, who cares? I don’t want to go through this again. I’ll never play the trumpet. Good luck.

July 9, 2024 @ 3:35 pm

John, great to hear from you.

“ If I were you I’d get the operation.”

Noted, thanks.

We could tell from your article that you have had and continue to suffer considerable pain. Not nice.

I’ve just had my first cataract operation done and go in tomorrow for a pre-op assessment on the other eye. I had to make a good case to my optometrist to get it done on our UK National Health System, at no cost to me, which is good of course. I don’t think I’ll be so lucky with my Dupuytren’s condition. I’ll wait a few months for the cataract business to settle down then make a decision on my hand.

It’s not sometimes fun getting old is it?

Best wishes, Peter

btw “ I’ll never play the trumpet.” You never know. It’s good to have challenges as we get older, right?

July 10, 2024 @ 7:21 am

Good luck, Peter. An update: My pinkie is 90 percent back to normal and pain free. I’m doing daily exercises and weekly physical therapy. That has helped a lot. It’ll be another six weeks before I have enough strength to lift weights but my life is pretty normal now. The doctor told me I almost waited too long to get an operation. If you catch it early, as my sister did, there is less pain and faster rehab.