Ghardaia: Algeria’s most traditional city likes the way it is

(Director’s note: This is the third of a series of blogs on Algeria.)

GHARDAIA, Algeria – I walked slowly through the back alleys of Algeria’s most conservative city, where Islam’s grip on society is just a little tighter and where tourism is more of a threat than a lifeline.

I tried hard not to look like one of the few tourists who make it through these narrow walls. My cell camera was buried in my pocket. My notepad laid in my other pocket. I wore faded jeans, nondescript Merrell shoes and a black parka. I could pass for an NGO flunkie.

Approaching me came two married women. I could tell. No, I didn’t see rings on their left ring fingers. I saw them dressed in full-length white robes, covering them from head to toe – except for one eye. I could see their one exposed eye rise in astonishment as our paths neared.

They quickly ducked into an enclave, making sure their backs were turned to me. And they waited. I passed. They then emerged and continued down the path. I’m used to having women turn their backs on me. I’ve never had them do it out of fear.

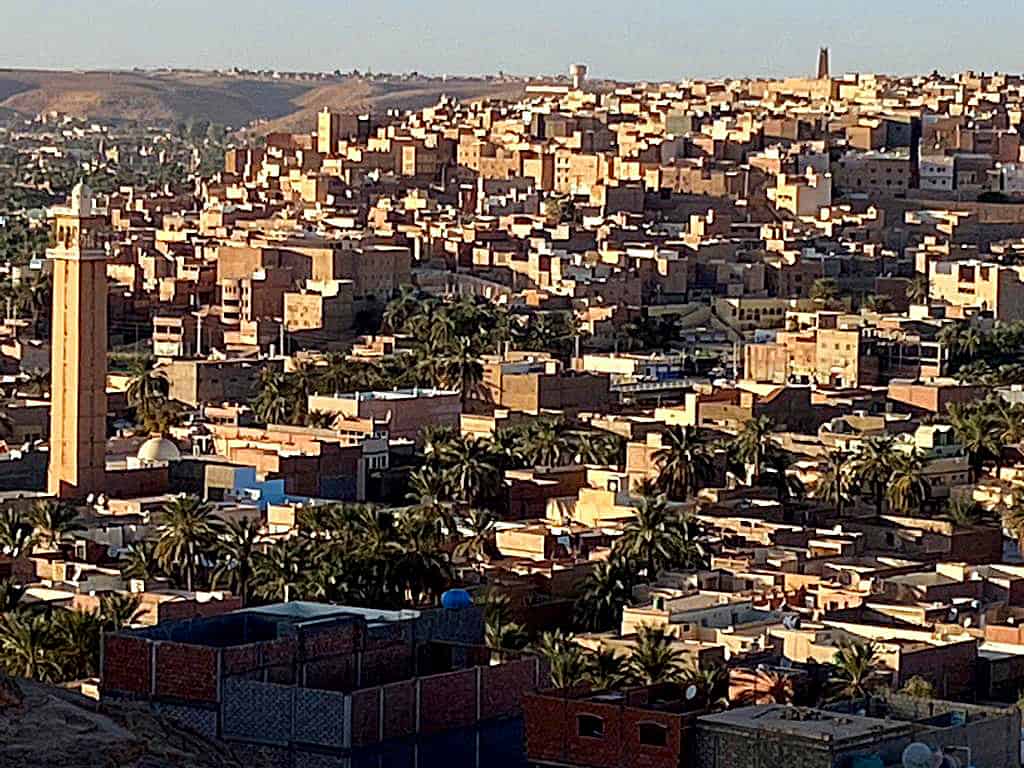

This is Ghardaia, one of Africa’s greatest paradoxes. This city of about 95,000 people features five UNESCO World Heritage Sites, an eye-catching skyline that looks like a Cubist painting and ingenious architecture that can cool temperatures hitting 122 (50 celsius) in summer. Yet few travelers come to see this smorgasbord of off-the-beaten path culture.

Few are allowed.

I was lucky. Earlier this month I joined my travel club, Travelers’ Century Club, on a nine-day tour of Algeria. Our second stop after touring the deep Sahara Desert was this most conservative city in a conservative country.

Getting there

Ghardaia is difficult to reach. The government makes it hard. Besides requiring a group tour, permits and a guide, Air Algerie’s inane timetable added hardship to an already difficult first two days. After getting three hours sleep in my tent in the Sahara and spending all day in the desert near Algeria’s southeastern border, we flew out of the desert oasis town of Djanet at the comfy hour of 12:45 a.m.

We had no direct flight for the 1,000-mile (1,657-kilometer) journey to Ghardaia. Instead we flew back to the capital of Algiers, landing at 3 a.m. We then spent five hours hanging out at the drab domestic airport gate until our flight at 8:35 a.m. We backtracked south for 380 miles (610 kilometers), landing in Ghardaia at 10 a.m.

Meeting our bedraggled crew was Hussein, a tall, handsome mid-20s college graduate of Eastern European history who sported a trim beard and English as good as mine. Dressed in a sirwal, the traditional long pants with the crotch hanging below the knees and a white skullcap, he asked us if we wanted to first sleep in the hotel or tour the city.

With the hotel 30 minutes away and us receiving a second wind, we all agreed to hit the town. First some ground rules: No shorts. No smoking. No taking pictures of the married women in white.

“They hate being in social media,” Hussein said.

Sorry, Hussein. Some in the group had fast hands and were more inconspicuous than I. Also, no taking pictures of children. That pretty much left shopkeepers and mosques. Nevertheless, we agreed and went directly into the heart of the city.

Ghardaia appears like a sandcastle built with Legos. At the top of a hill stands a tall watch tower, used to warn of the many groups of bandits that plagued the city through the centuries. It cascades down in a wave of sandstone structures in various shades of beige. Splashes of turquoise not only add some beautiful color, but they are easier on the eyes when the summer sun can blind them.

Our first stop was in the 11th century neighborhood of Tagnent, one of the UNESCO sites. We visited the smallest, most modest mosque I’ve ever seen. It was one story with three arched openings and no doors. Inside were enclaves where the Imam gave the public prayer five times a day. Unlike all other mosques I’ve seen, this one had no minaret. It had no loudspeaker. It was as modest as its white paint.

Built in the 11th century and refurbished in the 1940s, it was the most extreme example of the modest mosques in town. I always thought mosques were built as the most elaborate tributes to Allah. I’ve been to the Great Mosque in Istanbul, the Blue Mosque in Cairo and the Sheikh Zayed in Abu Dhabi among others. Each one was more spectacular than the next, with their brightly colored walls, massive prayer rooms and elaborate carvings.

“It’s a simple mosque so when the imam talks of poverty, he’s not a hypocrite,” Hussein said. “Even in Algiers, the capital, they built a huge mosque. They could’ve built a hospital there. It would be a great investment.”

Ghardaia architecture

The weather was pleasant: 63 degrees (17 celsius) and overcast. But in summer, Ghardaia turns into a tinderbox. It’s just north of the center of Algeria’s Sahara Desert and in July and August the 122-degree temperature makes air-conditioning as important as air.

Few homes have it.

Instead, the city uses ingenious methods in architecture to naturally keep buildings cool. Hussein rubbed his hand against a wall. Most of Ghardaia’s walls have bubbly paint, a massive collection of tiny curls. He said these curls provide enough collective shade to reduce the heat inside by 20 percent.

“When it’s hot outside, it’s cool inside,” said Ibrahim, our other guide. “When it’s cold outside, it’s warm inside.”

Roofs of the homes stay open, allowing air to circulate. If it rains – and Ghardaia gets less than 2 1/2 inches of rain a year, they just throw a blanket over the opening.

The narrow alleys also curve into what amounts to a giant maze. This creates constant shade. Initially, comfort wasn’t the reason behind the curvy streets. It didn’t take long for me to get lost. Imagine bandits trying for quick getaways with a sack full of loot.

“It’s a maze to stop thieves and bandits,” Ibrahim said. “If they’re inside, they get lost and they can be captured.”

The more we walked, the more we saw married women in their white cloaks, called an ahuli. They became less of a novelty than they did a collection of little ghosts flying in and out of alleys.

Women’s wear in Muslim countries is a bone of contention to the West. Few understand how much it varies. Algeria is my 19th Muslim country. Each one is different. Many women in Turkey, Indonesia and Uzbekistan wore stylish, sexy clothes. Yes, women in Saudi Arabia wore burqas. But when I was there three years ago, I didn’t see many. And it’s by choice. Not by Saudi law.

It’s the same in Algeria. The women in Ghardaia cover themselves out of respect to tradition, not in fear of arrest. It’s also confined to very traditional cities such as Ghardaia. I never saw these robes or even a burqa in Algiers. Women in Algiers could pass for women in Madrid.

But these married women in Ghardaia made me feel like I had found a hidden corner of Islam, with all its trappings. I don’t have sympathy for these women. I know this isn’t law. I was more content that Westernization hadn’t infiltrated this part of Algeria.

That raises the hurdle facing Algerian tourism. Unlike in Saudi Arabia, which is trying to diversify its economy away from oil by promoting tourism, Algeria has done little. It is content to live off the hydrocarbon revenues that have made Algeria the ninth richest country in Africa.

I wondered what would happen to Ghardaia, such an astounding snapshot into Islamic life, if these narrow alleys were filled with tour groups as big as our clan of 13 people. Yet when I asked Hussein what is the biggest problem facing Ghardaia, without hesitation he said, “Mass tourism.”

Huh? I’ve seen only a couple other tourists besides us.

“It’s starting,” he said. “You don’t go to the desert. You go to places where people live. And that makes people mad. It’s why you must take a guide. Villagers don’t want to be disturbed.”

He said in October 2022, 700 people visited Ghardaia. In December last year, 1,300 came.

“Numbers are rising,” Hussein said. “There are hundreds a month. Hundreds is too much here. If it’s thousands, it’s a problem.”

I asked him, as a tour guide, wouldn’t he like to see more tourists to make more money. He thought for a second.

“I’d like to keep the number where it is.”

Lunch

Continuing a theme that we would continue all week, the food was fabulous. Hussein took us to a place called Hama. We walked up a staircase just wide enough for one person into a big room that looked like the inside of a harem. Elaborate red and maroon carpets covered the floor under a tent-like roof.

Low couches and cushions lined the walls. All the tables had wooden trays with two round holes.

“Maybe it’s for monkey heads,” said Anthony, a Brit-Irish living in Portugal.

Actually, it’s for zfiti, Algerian bread chopped up and cooked in a mix of tomatoes, garlic, spices, pepper and olive oil, all served in a long metal tube called a mahras. I had the evaporated chicken, a big, juicy chicken breast cooked in aluminum foil. It came out so soft, the meat fell off the bone with a touch of my fork. The best dish, however, was meghlouga. It’s like an Algerian pizza: two thin pieces of flatbread stuffed with onions, carrots, garlic, tomatoes, salt and herbs. Light, tasty and healthy, it cost all of 250 dinars, or €1.70.

The hotel

By the time we were halfway through our afternoon tour of Ghardaia’s engineering feats in collecting water, camping out in deserts and airports followed by a full meal finally took their toll. We were nodding off on each other’s shoulders.

After a 30-minute ride to the hotel, we dragged each other to the hotel’s palm tree-lined terrace like wounded Vietnam soldiers. The Arkham Guesthouse looked like a palace online. Built in an actual oasis, it was surrounded by palm trees with a small pool and tasteful outdoor seating.

But when we arrived, the palm trees looked as if they survived a napalm attack. The pool bottom was scarred. Then we got in the rooms. No towels. It was 5 p.m. and no one had towels. None were dry anyway. Some people had no water, no toilet paper and no heat.

I checked into my top floor room then the cute, diminutive hotel manager brought me down one floor.

“There’s a problem with your water,” she said.

Good. Only one problem. My shower’s hot water trickled out of the faucet like toothpaste out of a tube. My toilet had no flusher. The worst part? It was cold. It was colder than outside and it was dipping in the 50s. I tried reading under the covers and my hands shook so much I couldn’t follow the type. I put a turtleneck over my sweater.

After dinner, which was admittedly excellent with chicken couscous and a large array of vegetables and salads, the woman got me a space heater. It worked. I got a fitful 10 hours sleep. I needed it. Everyone did.

Eco Village

The next day we visited the market and shopped for souvenirs, fighting no crowds as we were the only tourists we saw. As the sun began to dip, we were driven to what can only be described as Ghardaia’s wealthy suburb.

Ghardaia’s Eco Village sits atop a cliff above a forest of palm trees with the town’s mosaic of a skyline below. It consists of long, straight avenues lined with burnt orange stone two-story buildings featuring sand-colored trim. They were covered in bubble paint.

This neighborhood is a brainstorm of Ahmed Noah, a local ex-pharmacist who took the environmental principles of the lower village and put them in a modern setting. In 2004, he built narrow paved roads, put Islamic phrases on the walls and added attractive window shutters. He also added parking spaces. Healthy looking kids played soccer in the streets. I didn’t see a spot of trash.

Individual homes cost about €30,000.

It all looked as modern as those artificial urban neighborhoods in Denver that look like giant outdoor residential malls. The only thing the Eco Village was missing was an Applebee’s.

But no Applebee’s has a sunset like Ghardaia. The sun painted the villages below in a golden glow. Palm trees slowly swayed in the gentle, cool wind. We were headed to the airport. We were headed north in the same country but many worlds apart from Ghardaia.

If you’re thinking of going …

How to get there: Air Algerie has one morning flight every Tuesday and one evening flight daily from Algiers to Ghardaia. The 90-minute flight starts at $33 one way. However, the Algerian government requires permits, guides and a group tour to visit Ghardaia. Organize a tour. TCC used Algeria Tours 16, https://www.facebook.com/Algeriatours16/?_rdc=1&_rdr, algeria.tours16@gmail.com, 213-773-62-0805. Owner Wassim Allache, is well traveled and is fluent in six languages. He handled everything for us with nary a wrinkle. The overnight trip was part of a nine-day Algerian tour.

Where to eat: Restaurant Hama, 213-697-142-116. The best place for traditional Algerian food in town. In fact, it’s the only place. Excellent selection and quality with main dishes starting as low as 250 dinars (€1.70).

When to go: October-April. High temperatures range from 61 in January to 79 in April with a low of 41 in January. From July highs average 104 and can hit 120.

For more information: Tourism Algeria, https://www.tourismalgeria.com/index.html, info@tourismalgeria.com.

December 26, 2023 @ 4:51 pm

All I can say is “WOW” This was amazing. Thanks for sharing.

December 27, 2023 @ 8:06 am

Thanks, Alice. I was expecting a bombardment of hate mail for not condemning Algeria for the wives’ cloaks. Thanks for the thumbs up.

December 26, 2023 @ 6:33 pm

Fantastic article John, interesting and informative and the pictures are great.

December 27, 2023 @ 8:05 am

Thanks, Yvonne. It means more coming from you.

December 29, 2023 @ 8:10 am

Beautiful descriptions and accurate names/ destinations. I appreciate your record keeping!

In fact, my friends will love your writing! Thank you! And thanks to Anthony Bailey for outstanding fotos.

December 30, 2023 @ 3:53 pm

Thanks, Krista. It was great meeting you and I hope all of us meet again next year. Tuesday I’m posting about the three Roman cities from a Rome resident’s point of view.

John

January 9, 2024 @ 10:26 pm

John, I would like to say that I follow your blog and appreciate your insights about the towns in Italy. I know you have traveled for many years world-wide.

For this trip, I know you are simply reporting on what you saw and heard. But I do take issue with the line, “I didn’t feel sorry for them (the married women),” and the reasoning used — “that it is not the law” that decrees a married woman must be covered in a shapeless white gown from head to toe. I’m not sure why you felt the need to interject your opinion in an otherwise unbiased travel blog.

I know from my knowledge of history (and life today) that traditional laws about how women should dress are really enforced by society. No law on the books is followed unless upheld by the individuals who agree to the culture it creates.

After reading your article, in which the few quotes are from a male guide, I would say that the reader does not know enough about the society you’ve described that dictates the particular clothing of a married woman described here.

You do mention at one point a woman was afraid to be seen looking at you. But this aside,

I would say this to the male guide: If you truly believe that “married women like it this way,” his town should be unafraid to open a shop with all types of Muslim-appropriate clothing. Only then will that city truly know if all, some, or no women, “like it this way.”

Just my thoughts.

January 16, 2024 @ 5:54 am

Good points, Kathryn. Traditional Muslim women’s wear is a touchy subject and hard for Westerners to relate. I did talk to women wearing burqas in Saudi Arabia four years ago and they said they’d feel weird if they didn’t wear one in their neighborhood. I didn’t get the impression they were frightened. They just didn’t want to stand out. Is it truly a choice? Legally yes. Socially maybe not. I think it’s a fine line.

September 15, 2024 @ 2:18 am

great blog. Kathryn you need to know that every society, not just muslim, inculcate and push their values and norms. Including with regards to how people dress.

As a westerner I’ve noted many people from the west assume western modernity and it’s cultural values are somehow universal, of course as a person living in a society you will find others way of living to be strange even offensive to your sensibilities. but if you have enough self awareness you would realise the same applies to other societies and how they might view you, they also find their norms, well, normal, and anything else quite strange.

I guess as westerners we think, that all societies should draw a line where we do, and I think that’s because we don’t realise our notion of self and freedom are a product of a specific culture, it’s values, ideas etc. People’s conception of how to behave and what they ought to do, and the balance between desire and proper etiquette is determined by many things. do not think that Modern liberalism is a universal truth, you’ll find lockean justification for individual sovereignty is rooted in a beliefs that are not necessarily shared by other cultures.

September 15, 2024 @ 9:21 am

I agree with you on all counts. Americans, particularly those who don’t travel, think the only way of living is the American way of living and the only way of thinking is the American way of thinking. These people are shoving their value system down other people’s throats. Just as Westerners can’t understand why some (emphasize “some”) Muslim women wear burqas, very educated Europeans I meet over here can’t understand why so many American states allow people to carry loaded guns. Explaining Muslim dressing mores is easier. Unless a custom hurts a person, such as stoning rape victims, I accept pretty much all foreign customs. At least, I accept them more than American gun carry laws.