Hike through Lipton’s tea plantation a cool climb into another cool culture

HAPUTALE, Sri Lanka — She waved at me from behind a bush. Her smile revealed teeth so white they looked like sparklers in the dark night that was her face. She put the stem of a long tea leaf in her mouth and smiled. I walked over a few steps and snapped a picture that may end up on my wall or in the Los Angeles Times. Her light pink sash over her brilliantly turquoise sari made her look more like a fashion model than a tea picker. Her red dot, the Hindu eye, seemed larger on her forehead than most.

When she rubbed her fingers together afterward, I didn’t hesitate. I enthusiastically nodded and pulled out my wallet. I looked cautiously both directions and put my index finger to my lips. She did the same. I handed her a 20-rupee note worth about 12 cents, low, in between the tea leaves into her hand. I whispered, “Is-TOO-tee.”

“Thank you,” she whispered back. Her smile was more revealing of a perfect cultural exchange than the come-on to a love-starved solo traveler.

It came near the end of a 14-kilometer hike up through one of the Lipton Tea plantations. Sir Thomas Lipton, the Scottish tea baron who founded the most popular tea in the English-speaking world, owned this land from about 1890-1930. It covers some 2,500 acres, stretching up to over 5,500 feet into the clouds. Today, tea contributes $700 million into the Sri Lankan economy, the fourth largest producer in the world. Tea plantations cover 727 square miles, about 4 percent of Sri Lanka’s landmass.

The landmass I’m on is an absolute mountain, a green, undulating garden of tea. It also has some of the most breathtaking views in Sri Lanka.

Inspired by Haputale’s cooler temperatures, not to mention my sloth-like existence through my first week on the beach, I needed to hike. I need to sweat somewhere besides an Internet cafe. I first went to Heputale’s tiny train station and inquired about the famous one-hour train ride to Ella, just to the north. It is supposedly the prettiest ride in Sri Lanka. But the train station was a disaster. Only two people were there: a distinguished, round-faced Tamil with a salt-and-pepper moustache who told me I had to wait 90 minutes before someone would arrive and reserve me a rare seat in first class. Ninety minutes? It was already 9:30 a.m.

Meanwhile, a random-toothed fossil with a torn robe and wild look in his eyes kept mumbling something to me in what I assumed was Tamil. Maybe he was rattling on about the Civil War or channeling some Hindu god. Maybe he wanted my Clif Bar. I don’t know. I just had to get out of there.

Not wanting to wait until the heat of the day to hike. I bargained a tuktuk driver from 500 to 425 rupees (about $3.50) and took off toward the tea leaves. We climbed for 25 minutes before he dropped me off at the foot of the Dambatenne Tea Factory. Lipton built the plant in 1890 and it’s now run by the Lankem Tea and Rubber Plantations.Surrounding it is a village with a small collection of roti shops across the crude tuktuk stand from the factory. A narrow road cuts through some small wooden houses where the 400-plus tea pickers live.

As I started to climb, I passed the village school. A short, young male teacher in his 20s was surrounded by little boys and girls. All the boys were sharply dressed in white, short-sleeve shirts with black ties and blue shorts. The girls all wore white dresses. It all looked so preppy and formal. Then, as I turned to continue my climb, I heard a “WHACK! WHACK!”

I turned around and the teacher was holding what looked like a stick. A little boy was holding his ass. He had been spanked. Apparently, this was common. He didn’t utter a sound.

From there the only people I saw were women up to their waists in tea leaves and men supervising them from afar. At one junction, I saw a long line of women, all carrying giant white bags filled with tea leaves. A man in front weighed them and wrote numbers in a ledger. The sun was out. So was a cool breeze. The view of the green landscape was stunning. As far as manual labor goes, this seemed like one of the better gigs.

The tea pickers’ job isn’t easy, though. They all hung giant baskets on their shoulders. From a distance, they look like giant insects. The women would tear off the leaves with both hands and toss them in the basket over their heads. It was one continuous flurry. They moved down the narrow paths between the hedges. They make $4 a day. Nearly all were Tamil. During the 19th century, unable to find Ceylonese to work the plantations, the British imported a million Tamils from South India to do the job. They’re still here, all living in very rudimentary quarters at the foot of the hill. The women all wore head scarves and long sleeves. The weather was perfect, maybe mid-70s but I didn’t know if they covered up for warmth or religious modesty.

While on the job, the only times their eyes came up was to smile at me as I walked by. For once, a manual laborer-photographer relationship was not confrontational. We’d make eye contact, I’d hold up my camera, they’d nod and I snapped away. Only one other time did a woman ask for money and I did not hesitate to break the photographers’ cardinal rule. I don’t care. I’m invading their privacy. Screw the pros. I’m a hack photographer, and I want a picture for my wall.

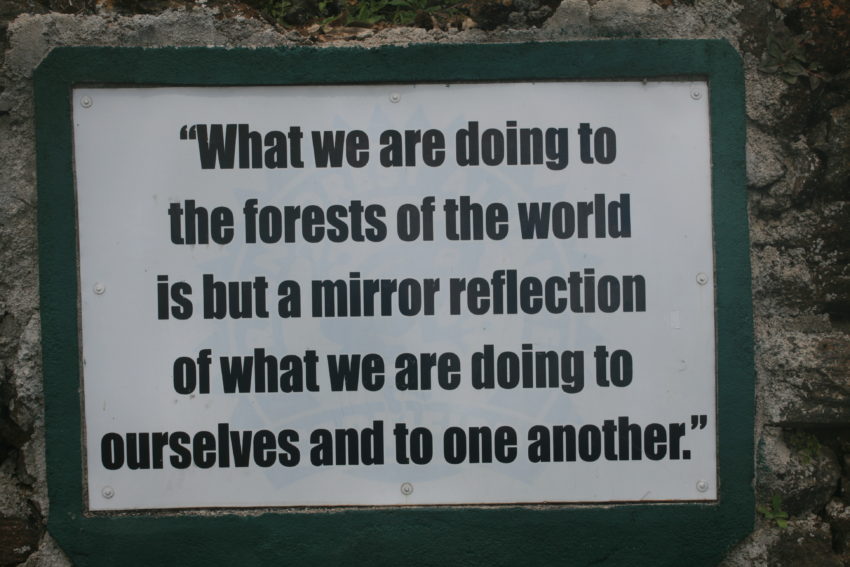

About halfway up, a man stopped me. He was burly and had a safari vest over a white polo shirt and a white Ben Hogan hat. Completing the odd ensemble were knee-length shorts reaching the top of knee-high blue socks with horizontal orange stripes. He looked like he borrowed them from the 1965 Chicago Bears. He said he ran the place and his name was Moorthy. He told me he has 400 people picking tea leaves for him and they make a minimum wage of 18 rupees a day. It wasn’t until later that I calculated 18 rupees as about 70 cents a day or $20 a month when I realized he was full of shit. So was his claim that he wrote all the environmental messages that are printed in big signs all along the path. They say things like, “The fate of animals is indissolubly connected with the fate of men” and “Water is the one substance from which the earth can conceal nothing. It sucks out its innermost secrets and brings them to our very lips.”

If he wrote this environmental poetry, I wrote the Koran.

Not thinking how it would harm his fake identity, he asked if I had a spare pen. Then he wrote his full name in my notepad. Suppiah Thirugnana Sambanda Moorthy is his name, allegedly. I walked away and made a subconscious feel for my wallet.

I kept climbing. It’s 7K to the top and each switchback offered a more breathtaking view of Lipton’s place. Neat, individual rows of green tea plants climbing steep hills and fading into mist. Villages of little shacks and red clay roads surround a pagoda sticking above the plantation. It was so peaceful I could’ve sat down and napped.

When I reached the top, I saw Kristiana and Jana next to a snack shop sitting down to a lunch of tea and roti. They paid 1,000 rp for a tuktuk driver to haul their cute little behinds up in about 15 minutes. They passed me as I was sweating up the steepest set of switchbacks. When they saw me, Jana screeched, “Kristiana you win.”

Huh? Kristiana bet I’d arrive in 45 minutes, Jana in 90 minutes.

“Jana!” I said, “have ye little faith?”

We sat and talked for an hour. I nibbled on the collection of hot, Hot, HOT rotis and we all waited, cameras locked and loaded, for the sun to break through the fog. All we could see was the perch from which Sir Lipton would sit overlooking his empire while entertaining royalty. It is quite a view. With a cup of tea, I imagine it’s as peaceful as any spot on earth. Too bad I think tea is one of the most vile swills known to man. Too bitter. Too hot. When it cools, it’s even worse. I don’t get it.

We all reunited back at the guesthouse where, bored before dinner, I perused the guestbook. Hashan, the young guesthouse owner along with his pretty sister and her mother, the great cook, has made quite a name for himself here. Huests called him, “The Prince of Haputale.” One Danish couple gushed, “Hashan, you are the best. Don’t ever change. Be yourself. You have a wonderful gift.”

Hashan seems a little light in the loafers but he turned pretty macho when I asked him about the war. I mistook him for a Tamil. I shouldn’t have. He’s quite black but this is Tamil country. He was not offended. He likes the Tamils.

“It wasn’t Singhalese versus the Tamils,” he said. “It was the Singhalese versus the Tigers. I never insulted the Tamils by calling them the Tamil Tigers. It’s only the Tigers.”

I asked him how the Tamil Tigers emerged.

“It’s like you live in a home and you can’t leave the home,” he said. “The people in the house tell you all the horrible things outside the house. You grow up thinking they’re horrible people and your children think they’re horrible people.

“My friends, the Tamils, they did not want an independent state.”

I had to talk to Hashan. No one else was talking. In what would be a great cover photo on a story about how modern technology has returned the art of communication, I was joined at dinner with eight other people. The two Czech women, another Czech couple and a French-Chinese couple were all pecking away at their iPhones, barely acknowledging each others’ existence except when they showed something on their iPhones.

Cell-less, I instead ordered a cup of tea. Maybe I developed a taste for it while spending an entire day within its roots. Maybe I wanted to drink like a local. I was not thirsty. But Hashan brought out a cup and I drank it Sri Lankan style: with milk and sugar. It wasn’t bad. In fact, I really liked it.

In Sri Lanka, high among the mist and the tea leaves and the gentle tea pickers, how could I not?