Jeddah: Saudi Arabia’s Red Sea jewel opening its gate even wider for the world

Jeddah is Arabia’s cosmopolitan capital on the sea

(This is the second of a three-part series on travels through Saudi Arabia.)

JEDDAH, Saudi Arabia — The plane begins to fill and I wonder if this domestic Saudi airline has a dress code. I look around the Flyadeal jet and realize I’m about the only person not wearing what looks like large white beach towels over loose cotton pants. Women’s eyes peer through their burqas. I suddenly feel self-conscious wearing beige trousers and a polo shirt.

I see a white, bespectacled woman wearing a robe and a hijab which leaves her face uncovered. She looks as if she could be from St. Louis. I ask her, “You American?”

“Yes, but my husband is British,” she says.

He’s an overweight, pasty Englishman with thinning hair and glasses, looking entirely out of place in Muslim clothes but not nearly as much as I feel. After landing, on the bus to the terminal I ask a black man standing next to me where everyone is from.

“We’re from all over,” he says. “I’m from the UK.”

“You going to Mecca?”

“Yes.”

“But the Hajj isn’t until July,” I say.

“This is a pilgrimage. It’s a mini Hajj, and they happen all year round.”

Before I can ask a dozen questions that come to mind, he escapes through the packed arrival terminal. However brief, I can not have a better introduction to Jeddah. Yes, it’s the gateway to Mecca for the Hajj, the Muslims’ pilgrimage to fulfill one of the seven pillars of Islam. However, Jeddah also belies the closed society Saudi Arabia projects to the world and is trying to change through tourism.

As I wrote last week, in September Saudi Arabia began offering tourist visas for the first time (except for 2007-09) and Jeddah is one destination it’s highlighting. This seaside city of 4 million people is the commercial and cosmopolitan center of the country. While the rest of Saudi Arabia has been closed off for generations like a private sandbox, Jeddah is the one place that has welcomed outsiders. Ever since the 7th century, millions of Muslim pilgrims from around the world have passed through here on their way to Mecca only 40 miles to the east.

This influence from the outside world has made Jeddah a more open-minded, liberal pocket in a country castigated for human rights violations and religious intolerance. Hidden in the shadows of Jeddah’s 1,300 mosques, private observation of other religions is overlooked. Western dress is more common. Its beaches and boardwalk along the Red Sea are among the most majestic in the Middle East. Its ancient port is a UNESCO World Heritage site. It has Saudi Arabia’s most bustling souq. It has an entire Indian neighborhood. In fact, it’s said the Jeddah accent is one of the most distinct in the Arabic-speaking world.

As Jeddans proudly boast in their city slogan, Jeddah Ghair (Jeddah is Different).

I remember Jeddah from my childhood. My uncle, Howard Eberhart, taught engineering at the University of California and spent three years teaching in Jeddah in the 1970s. He raved about the raw beauty of the seascape and the people.

I can tell on the ride in from the airport that Jeddah’s vibe is different from the capital of Riyadh. It’s like going from a warehouse to a beach house. The modern apartment houses in colorful wood and concrete can pass for apartments in Santa Monica. Palm trees line the road. I keep thinking I might hear the Beach Boys drift through the warm 80-degree air. However, while I don’t see any burqas, I don’t see any shorts and halter tops, either. On Day 6 of my trip, I’ve given up hope seeing a bare leg. I’ll settle for a full head of long hair.

I wind up seeing plenty. Jeddah is one place in Saudi Arabia where they let their hair down.

Jeddah’s old town

The stone gate stands two stories high with an arch between two rounded barriers. It looks like a small castle on the sea. Until 1950 when air transport became more common in Saudi Arabia, about 80 percent of foreign pilgrims came to Mecca via the Red Sea and through this gate.

Today the UNESCO Heritage Site is a gateway to Jeddah’s Old Town, the best in Saudi Arabia. I walk in and unlike many public markets in the Middle East, it’s a friendly place with no one barking at you to buy a carpet. Merchants greet me with smiles and waves. A man outside his butcher shop gives me a thumbs up as I take photos of his two pigs hanging from hooks, skinned and slack jawed. A well-groomed businessman in glasses and a white thobe, the Muslims full-length robe, cleans his teeth with a stick.

I walk by a crude cafe where a man sits on a plastic chair watching the news on TV. Two old men sit at a table with milky coffee next to a young man laughing in his cell phone. I’m the only Westerner in sight. I have the whole place to myself.

Then I’m not.

I walk to one of Old Town’s main sites. Naseef House is where King Ibn Saud, considered Saudi Arabia’s founding father, lived in the 1920s. It’s a massive two-story house lined with shuttered windows in the shade of a huge tree hovering over the front porch. In front of the house pose about 40 men and women. I ask the photographer, a young man named Mohammed in a white thobe and holding a cane and a camera, who they are.

“We’re all photographers from around the world,” he says in excellent English. “We’re called the Raw Shooters. Do you want in the picture?”

Before I know it, I’m in the second row next to a pretty woman in a hijab. I return to Mohammed and tell him how much I like Saudi Arabia but …

“… I’m having problems meeting Saudis,” I say.

“Come here,” he says. “I’ll introduce you to some.”

Interview with six local men

He peels off about six men, all in their 20s and 30s with nice cameras around their necks. All are young, educated, open minded and speak superb English. No one is wearing a thobe. I proceed to hold an impromptu press conference in the middle of Jeddah’s Old Town.

I ask if they’ve seen any changes in Jeddah since the offering of tourist visas. Between October, November and December, the government averaged 45,000-60,000 visa applications a month.

“You can see the difference,” says Abdul, a flight attendant. “A year ago it was basically the locals. A few visitors who come to the market and pass by Jeddah and then go back to their countries. Now it’s increasing. Before it was only Muslims. Now it’s people from all over the world.”

They all talk about their eagerness to show the world that Saudi Arabia isn’t just about public executions and oppression of women. I ask what’s the biggest misconception the world has of Saudis.

“That we are terrorists,” says Sibba, a dental student. “We have oil fields everywhere, like at our houses. That we are gypsies, always aggressive. But we’re always loving. We’re always friendly. We love the insiders and we love the outsiders.”

I broach the subject of women’s rights. It’s a government that has gone from one of the most oppressive to allowing women, finally, the right to vote in 2015 and to have driver’s licenses in 2018. They can attend sports events and travel unaccompanied by a male.

The men welcome women’s independence, even more than some Italians I know back in Rome.

“I’ll give you an example,” Sibba says. “In my college, at my level, I have about 50 male students. But for the female students there are about 150. And most of them are on scholarships.”

Another misconception all Saudis tell outsiders is the myth about the burqa. They are not mandatory for women. They never were. Fewer women wear them today but even outside Saudi law they must deal with very conservative society’s mores.

“It’s about the community,” says Malek, an architect. “Before, people were more conservative. Now it’s like being with the society and fitting in, blending in. If she takes it off it’s OK. No one would talk about it.”

“It’s been like this a long time,” another says. “Some just don’t want to stand out.”

These men could be college kids in the Big Ten or young white-collar men in the workforce in Chicago. The only difference is these guys don’t drink. But like their brethren across ponds, their testosterone rages just the same.

When I ask if they can have premarital sex here, no one smirks as if they’re tired of the question. No one scoffs.

“Yes, we can have it,” one says. “We can do everything here.”

“But what about the arranged marriages I’ve read about?”

“Way less than before,” Malek says. “For example some of my sisters would want my mom to pick her husband. They don’t want to go through the hassle of dating. Like, we’ll get engaged, we’ll get to know each other and we’ll get married. But I have other sisters and brothers who’d rather have a relationship.”

Free speech still a tricky question

The elusive answer I can’t find is the level of free speech. Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MBS) opened up tourism to diversify the country’s oil-dependent economy. Yet dissidents remain in jail. He continually denies responsibility for the 2018 murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi.

“That’s not true,” says Akhmed, an administrator. “You can criticize the government. You can criticize MBS himself. You can even sue the king. It all comes down to respect. Say it with respect.”

“The women in jail for demanding rights didn’t show respect?” I ask.

“The problem is the women broke the rules when the rules were there for a reason,” Malek says. “I don’t agree with them back then but they were rules. They were so strong they wanted to fight that fight in their own ways. It’s unfortunate. I hope they do come out because now it’s allowed.”

I thank all of them and pose for selfies before continuing on. Suddenly, one of them taps my shoulder and pulls me aside. I won’t include his name and you’ll know why when you read his statement.

“Something I must clarify about what they said about free speech,” he says. “We don’t have it. We can not criticize the government.”

No, but they can criticize other governments. As I do everywhere, I ask my million-dollar question. What do you think of Donald Trump? The men remind me that Trump sold Saudi Arabia $350 billion worth of arms in 2017. It’s a deal the Saudis will never forget.

The men all do the same as everyone I’ve asked from Iceland to Laos. They smirk. Then Sibba has the best line I’ve ever heard.

“Everyone around the world thinks he’s an idiot,” he says with a laugh. “But he’s OUR idiot.”

Jeddah nightlife

It’s Feb. 22, nearing the end of Day 6 in Saudi Arabia and the closest thing I’ve come to alcohol is the bottle of disinfectant on my Hotel Centro Sheehan lobby counter. The accommodating hotel clerks recommend we apply it occasionally. Something about a virus starting to spread from China.

Surprisingly, I don’t miss drinking. This comes from a man who for the last six years has lived in Rome where wine is considered one of the four major food groups. I drink wine with every meal out; I drink beer with every soccer match I watch.

The weather in Jeddah is in the low 80s and its humidity about 60 percent. Yet I’m not screaming for a beer. Saudi Arabia’s strict alcohol ban is what keeps many friends from visiting, as if the country has a tax on air.

What I miss is the gathering places where people drink. If religion intoxicates the masses, alcohol masses the intoxicated. Bars are where I do my best research. Few people have a better finger on their country’s pulse than bartenders. Few people are more honest than locals after a few drinks. And everyone likes to discuss their country. From beer gardens in Oslo to hotel rooftops in Bangkok, I’ve learned where to eat, what to do and how they think.

But where do you learn this in Saudi Arabia?

There is no Hard Rock Riyadh — thank God. Saudis, instead, are crazy about coffee shops. They are all over. They serve everything from cappuccino to caffe latte to experimental coffee-based drinks to little snacks on the side. Yes, even Starbucks is here. It arrived in 2000, poisoning the culture forever more.

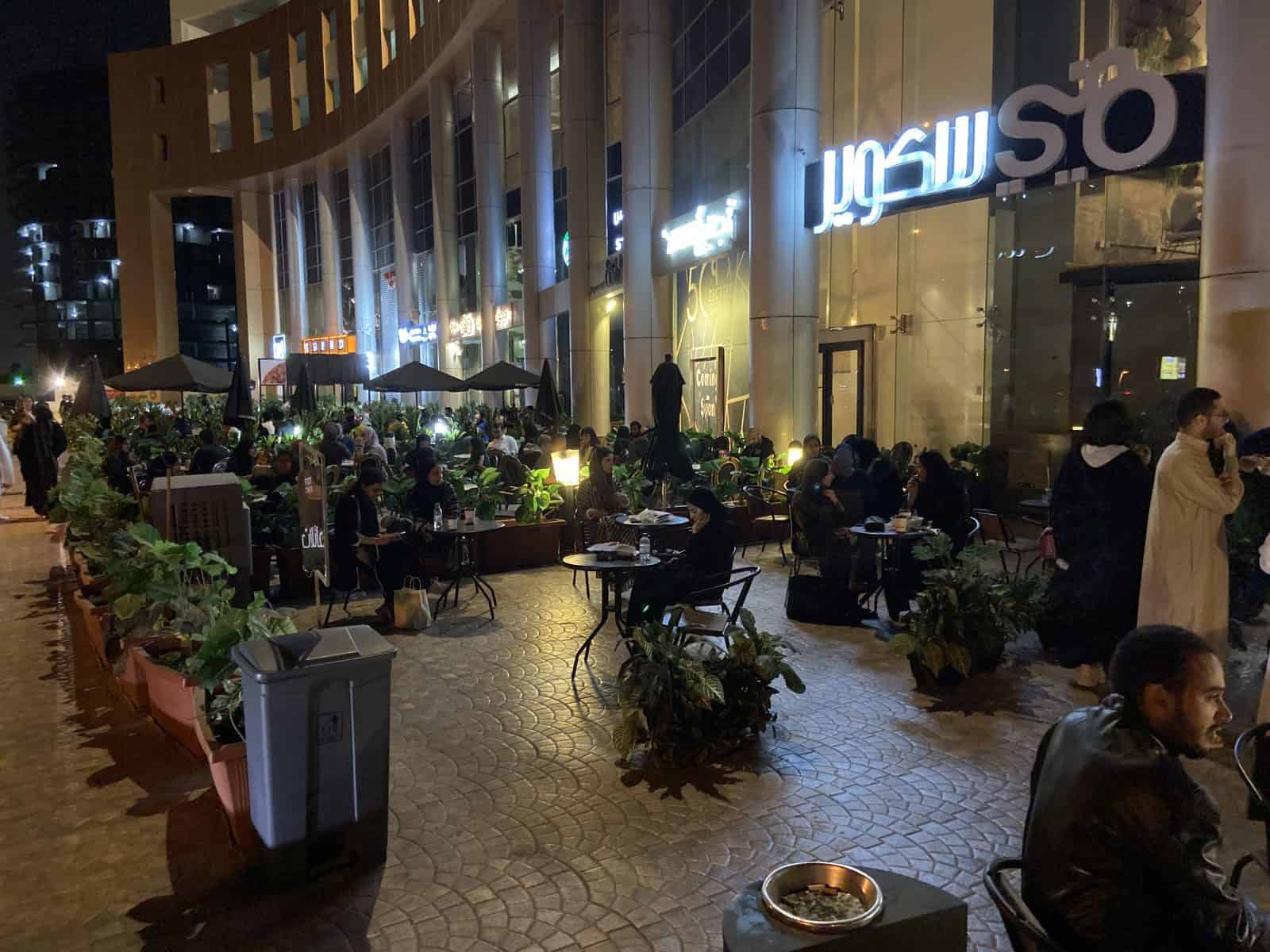

Cafes are where Saudis go. In the heart of Riyadh is The Zone, a huge public square lined with coffee shops and restaurants wrapped around an enormous fountain. On my last night in the country, I dine at a high-end vegetarian Indian restaurant called Ruhi and cafe hop with expats I meet there. Every cafe and restaurant buzzes with activity. The outdoor tables are packed. Men in thobes and keffiyehs and women in burqas, hajibs and loose blouses sip coffee and fruit juice and smoke from charcoal-blazing hookahs.

Medd Cafe is the place

In Jeddah, my new friends from Old Town tell me to go up Jeddah’s Corniche and hit Medd Cafe, THE place to meet locals (i.e. women, wink! wink!). The Corniche is a 30-kilometer walkway along one of the most beautiful stretches of the Red Sea in the country. A big part of Saudi Arabia’s tourist carrot, the Corniche is lined with beautiful, swaying palm trees and modern sculptures by such artists as Henry Moore.

In late afternoon a taxi takes me 30 minutes north of town where we race the sunset. I urge him to break every Saudi speeding law and he promptly arrives at 6:15, just as the sun approaches the horizon. I dodge about four cars as I gallop across the street, skip over some fenced-in shrubs and run to the boardwalk.

It’s a wide sidewalk along a sandy beach where locals sit around in folding chairs and on beautiful blankets, drinking tea from elaborately decorated pots or water from plastic bottles. It’s men, women, men with women, men in thobes, women in burqas, men in casual wear, women with long, flowing raven-black hair down to their shoulders. Children race around on neon-lit, battery operated tricycles. Children are not for want in Jeddah.

Jeddah’s sunset is one of the most beautiful I’ve seen: a flaming yellow ball in a sky of orange, maroon and gold. A warm breeze comes off the sea.. Couples and families stare out to the horizon in silence.

If this is the Saudi Arabia the country wants to project, who needs oil?

As the sky turns black and the lights come out, I hail another cab and he drives 15 minutes farther north to a huge building called Beach Tower. Walking around to the front I see it lined with modern cafes sporting international names. First Crack. Zanjabeel. Dijon Cafe. Each one is packed with pretty women in hajibs or fashionable pants and shoes. Men hang out in T-shirts, baggy jeans and ball caps worn backward. Rock music is played from an unseen speaker.

Here Michael Jackson replaces muezzins; ball caps replace burqas. I could be in Miami Beach.

Medd Cafe is at the far end of the strip. Beautiful young women look like they all came off Maybelline makeup ads. Men and women sit together and mingle, no one terribly flirtatious. It’s all very respectful. This is no meat market.

I order an outrageously priced drink called a White Moon Milk: white chocolate, rose water and pastacchio for 24 riyals. That’s 6 euros for a drink that could give children a 12-hour sugar rush. Then I realize I’m not in Miami Beach. I must wait 30 minutes to get served.

“You must wait until after prayer,” the young man at the counter says.

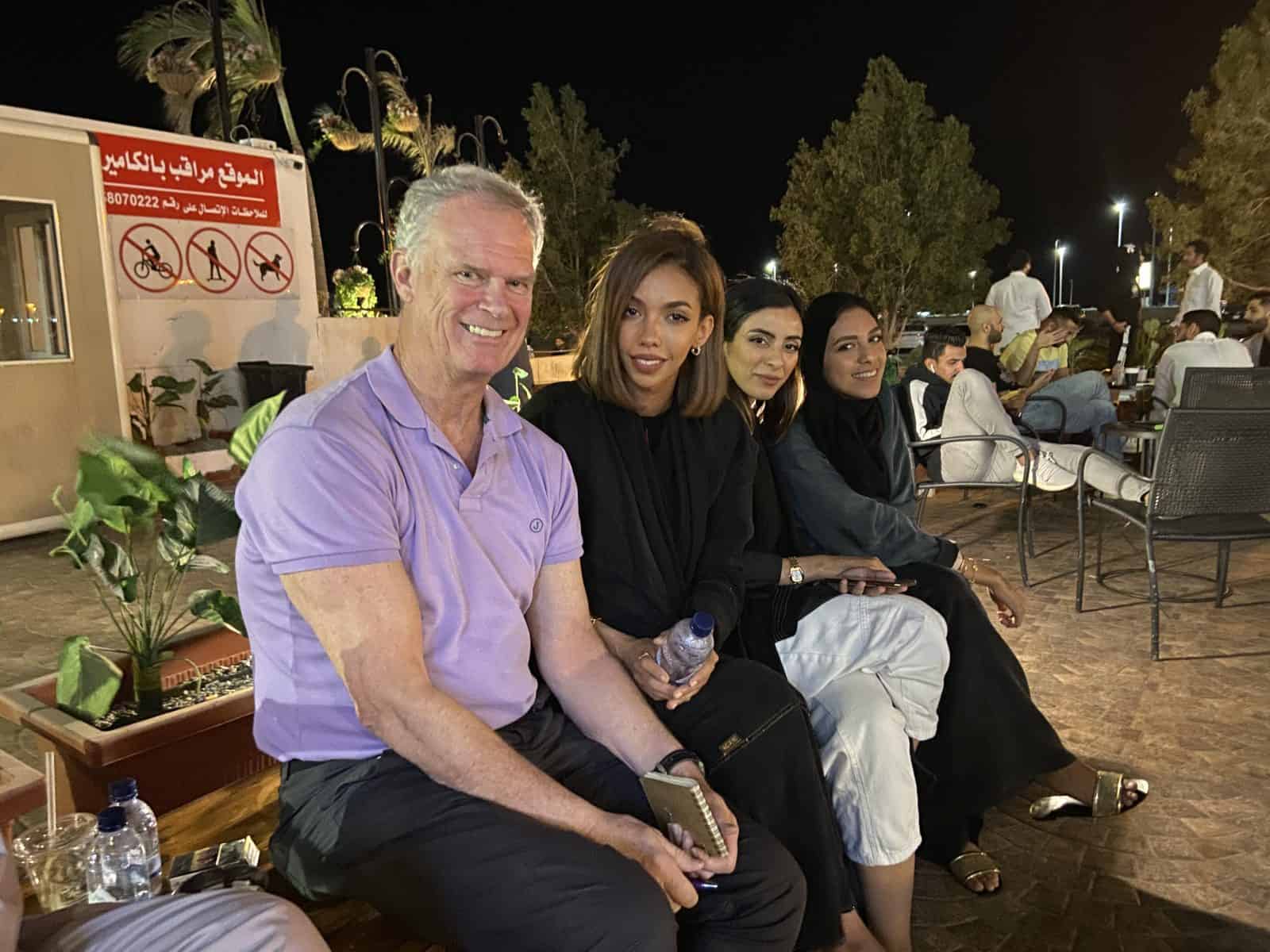

I walk out and hear the muezzin’s call to prayer from a mosque, shining like a lighthouse, about 500 meters away. A half hour later, I take my drink through the collection of benches and something happens that never happened in all my years in the U.S.

Three beautiful women wave at me.

“Why don’t you come sit here,” one asks. They introduce themselves in barely accented English. Shahad Al-Harbi and Nesrin Al-Harbi, both 24, and Malak Al-Harbi, 25, are all cousins and students in nursing school. They represent the modern Saudi woman: independent, beautiful, traveled. Only Malak wears a hijab. Shahad wears a light black jacket over a black blouse and Nesrin stylish white pants. All are beautiful with naturally dark faces, big brown eyes and thick, black hair. They could be actresses in a Saudi romantic film.

They’re all from Jeddah and drinking bottled water. Me being the only Westerner in the place, they ask the obvious question. What am I doing here? I tell them I’m a travel writer from Rome, and I take a bold step. Can I tape our conversation? They seem flattered. Is there free speech in Saudi Arabia?

Let’s find out. The woman who led the reforms to let women drive now was sent to prison.

They exude national pride, sweeping their arms toward the beautiful seaside and all the young people mingling stress free. They seem more than sincere in urging tourists to visit. They seem thrilled with the opportunity to meet others, like me.

“You come to Arabia,” Nesrin says. “You’ll see. All the people here are very friendly. This is our culture.”

I tell them many Americans equate Saudi Arabia with Osama bin Laden. Nesrin sneers as if sniffing bad mutton.

“Osama bin Laden,” she says, “is NOT Islam!”

Burqas not mandatory

I ask them about the burqa and why they don’t wear them. They never have, they say, but they have friends who do voluntarily.

“It’s a different culture,” Nesrin says. “They’re very conservative.”

They all rave about the changes they’ve seen. They all drive but it goes beyond that. They travel with difficulty but not from their government. Nesrin said she was stopped in the Boston airport and interviewed in a private room before being released.

I mention the Crown Prince and all three nearly genuflect.

“Thank God for him!” says Nesrin, holding her arms to the sky.

I ask them what they do for fun.“Everything we want, we can find it,” Nesrin says.

“Even sex?” I ask.

“If you want to do it before you get married, you can do it,” she says. “And there are many men available. Most of us don’t want to do it before we get married.”

It’s getting late and it’s time to leave. The women tell me I’ll never catch a taxi and Nesrin calls me an Uber. While I’m waiting, a man in a neat Fu manchu in a big American Yank tank calls me over and says, “Where do you come from?”

We chat a bit and I commend his excellent English. He said he spent three years studying in New York, and I ask what’s the one thing Saudi Arabia should change.

“Make marijuana legal,” he says.

“Did you smoke it in New York?”

“Every day!”

“What happens if you get caught with it here?”

“You got to prison for about five years.”

Soon, Nesrin comes back to check on me and the man quickly turns his attention to her. They exchange a few comments, she gives him a smirk, rolls her eyes and walks away, flipping her hair around like in a shampoo commercial.

“What’d he say?” I ask.

“He wanted my Snapchap.”

Jeddah’s best beach

During our conversation and after a couple of days in Jeddah I’m not surprised when they say they wear bikinis to the beach. I must investigate — solely for journalistic purposes, of course. The beaches around Jeddah are not legendary only because so few outsiders see them. Saudi Arabia has 1,640 miles of Red Sea coastline with little commercial development along the way. It’s a country of sand. How can the beaches not be beautiful?

An unscientific survey of locals had me settle on Silver Sands Beach. It’s an hour north of Jeddah and I nearly have the Uber driver turn back when the gate charges 160 riyals, more than $40. When I walk down the service road and reach the beach I know it’s the best 160 riyals I’ll spend the whole trip.

White Sands Beach is spectacular.

Laid out before me is a half-moon swath of fine white sand lined with palm trees. Wooden and white plastic lanais chairs sit two to a table, each with a big umbrella. The sea goes from sea green to turquoise to royal blue as it washes up on a tiny man-made island right out of a Far Side cartoon 100 meters offshore. The water is so clear I kick myself for not bringing my scuba diving C-card.

I see only six people: a British family of four and two local teenage girls wearing long shorts and tank tops. A young cabana boy sets me up with a padded lanais cushion about 10 meters from the water, not within shouting distance of a soul.

After about an hour of undisturbed bliss, the Brit walks by and says hello in English. He invites me to sit with his daughter, a former flight attendant for Saudi’s foreign minister, “Many pounds ago,” she admits. She married a local in charge of all in-flight services in Saudi Arabia and has been here 30 years.

They talk about all the changes in the “new” Saudi Arabia, about Neom, which sounds like a Nevada brothel but is really a $500 billion man-made city on marine land. We talk about the collection of man-made islands called the Red Sea Project. It all sounds like an Arabian theme park but it also sounds very ambitious for a young Crown Prince trying to step out of his dad’s royal footsteps.

The simplicity of this beach seems to trump it all.

However, clouds soon come over and while Jeddah gets virtually no annual rain, the skies chase me back for my last night in town. I meet Mehdi Mohammed, an Indian with whom I connect through a Pakistani friend back in Denver, where I lived before Rome. Mohammed, a tall man with hip glasses, has lived in Saudi Arabia since 1991, working for an international vitamins company.

He drives me downtown where we pass a big shell of a building, its vacant windows looking like blackened eyes. I remember seeing buildings like this in Beirut.

“That used to be the Trans-Continental Hotel,” he says. “But the Crown Prince built a new palace across the street and was told people on the top floor of the hotel could see him. So he had the hotel shut down.”

We eat at Aroma, a beautiful, modern, Saudi-themed restaurant with palm fronds and overstuffed chairs. I have a wonderful chicken stir fry and a tall, vanilla milkshake piled high with whipped cream. It’s as decadent as any alcoholic drink in New Orleans.

We have an awkward conversation about life in Saudi Arabia. He’s clearly uncomfortable with some questions and after we leave he grabs me by the arm and says, “John, be careful what you ask here. There are people around, cameras everywhere. I couldn’t talk about the Crown Prince in there.”

In the home of Arabia’s prison chief

Throughout the evening he tells me we’re meeting someone special. He drives us into a bland residential neighborhood and parks on a small, dark street. Greeting us at a huge gate is a diminutive man in a shockingly white thobe and white keffiyeh with a black headband. His short stature and fair skin somewhat give him the look of a ghost.

However, Zaki Asad Rahimi has been very visible in Saudi Arabia. For a week I’ve tried to decipher myth from fact about the country’s strict laws. Standing in front of me is the man who was in charge of Saudi Arabia’s prisons for 25 years. The thought overwhelms me. In one of the toughest legal systems in the world, this tiny man was in charge of all those they locked up.

His tour of his home is like the Crown Prince’s guest quarters. The first room has beautiful red velvet couches and tables with elaborate doily tablecloths topped with shiny gold dining wear. His entryway features a spiral staircase and a glass-encased sword, sheathed in a bejeweled casing, a gift from one of his many travels. He points to a crystal punch bowl that looks priceless.

“I don’t even use this,” he says with a laugh.

He has pictures of him with the king and the Crown Prince. He hasn’t just rubbed elbows with royalty. He worked for royalty.

Known as Zak, he is very international and speaks excellent English. He graduated in criminal justice from Sacramento State and studied the prisons at Folsom and San Quentin in California. As a servant serves us fresh fruit juice in champagne flutes, he talks about the difference between Saudi and American prisons.

“Our whole purpose here is rehabilitation,” he says. “What purpose is there to put someone in prison if they don’t get help?”

I can’t help myself. I ask him the question that hangs over every American’s head when Saudi Arabia surfaces. I ask about the public executions and their force as a deterrent. Saudi Arabia’s violent crime rate is 59th in the world. The United States’ is ninth. I ask him if he ever witnessed a beheading.

“I was there, at their side,” he says.

Yes, he accompanied the prisoner and the executioner to executioner squares all over the country, wherever the criminal committed his capital offence. I ask how they do it. Then, like an old football coach illustrating a basic fundamental, he brushes back his thobe and gets in the prisoner’s stance: On his knees, squatting low with his back straight and head up.

“Does he chop down?” I ask, more fascinated than appalled by this chilling demonstration.

“No. He cuts across. And they don’t feel a thing,” he says while he makes a horizontal cutting motion with his hand. “It’s real sharp. I swear to Allah, sometimes I am behind him and he did it like that. The sword went through and the blood goes and the head does not fall. That means the operation is excellent.”

Only two crimes for beheadings

He then debunks the public belief of random usage of capital punishment although dissidents and protesters are often listed as “terrorists” in execution reports. Free speech in Saudi Arabia is as frowned upon as alcohol and much more illegal. He says executions are reserved only for two types of criminals: murders and, he says with disgust, “hashish dealers.”

“People really try to smuggle hash here when they can get executed?” I ask.

“People do it all the time,” he says. “Many of them are foreigners.”

He says two weeks earlier a group of men stole about 1,200,000 riyals (about $320,000) from a cash machine and got caught within 24 hours. They will lose a hand each, he says.

However, he is also benevolent. Before executions, he often visits the family of the person murdered. They’ll talk. Sometimes the family will forgive and the execution is cancelled.

I must run to the airport but want to stay. Instead of the past, we discuss the future. Saudi Arabia’s is about to change. If all goes to the Crown Prince’s plan, a whole new influx of people will soon explore this mysterious land. The Crown Prince wants 100 million tourists by 2030. I ask Zak how open minded the people are about the West.

“I think they are,” he says. “There’s always the danger that they lose their own culture so they’re reminded of that. I’m always advising them to watch. All of this is new. New people are using it. People are really up for it.

“They’re up for anything.”

(Part III: Madam Saleh — Petra’s cousin without the tour buses.)

Jeddah: If you want to go …

How to get there: Flyadeal and Flynas, two domestic airlines, have numerous 1-hour, 45-minute flights a day from Riyadh starting at about $125 round trip.

Time to go: November to March. Temperatures range from 80-90. From April to October it ranges from 97-115. Average humidity year round is about 60-65 percent.

Visas: Visas required for 49 countries, including the United States, and can be acquired online at visa.mofa.gov.sa/visaservices/searchvisa for $124.

Where to stay: Centro Shaheen, Madinah Road, 966-12-618-888, https://www.rotana.com/centrohotels/kingdomofsaudiarabia/jeddah/centroshaheen, rooms starting at 562 riyals ($150). Excellent four-star hotel with mini-bar, pretty rooftop pool and a fantastic breakfast buffet in a central location.

Where to eat: Al Saddah, Hira Street, An Nahdah, 966-12-622-8296, https://www.alsaddahrest.com/, 11 a.m.-1 a.m. Authentic, non-touristy Saudi eatery with not even a sign in English. You order at counter and sit Saudi style on pillows and blankets. Serves all classic Arabian dishes such as lamb kabash, a huge plate of lamb, rice and sultans. With lots of side dishes and 7-Up, cost is 20 riyals (about $5.30).

June 4, 2020 @ 5:19 am

Hi John, Been following your Italian blog for a few years and have enjoyed it very much. We have lived in the UAE for 6 years where my husband is a university professor. I wanted to post a misconception regarding the use of the word, Burka.

4) Some Arab women wear a burqa.

NO, generally speaking. This is an item characteristic of Pakistan and Afghanistan and was imposed by the Talibans and it is not paramount in the Arab world, even though some countries such as Yemen have their own version of the burqa (or burghaa) which differs from the Afghan one.

It is not to be confused with the niqab, which is indeed commonly used in the Middle East. The differences:

The niqab is usually black and merely a face veil, the burqa is mostly light blue in colour and covers the whole body

The niqab usually leaves the eyes uncovered, while the burqa has a net over them

Women in the Gulf States wear wide, long robes called Abayas, usually in association with a shayla hijab that shows some hair and a niqab.

This information came from the link below which is an excellent source of informtion of the dress code for the countries in the Middle East

http://istizada.com/arab-clothing-the-ultimate-guide/

June 9, 2020 @ 9:32 am

Thanks. Duly noted. I always called it a burqa in Arabia and was never corrected.

July 27, 2020 @ 12:54 am

I think I like it -as it is now; everything seems orderly.

Thank you

September 9, 2020 @ 2:34 pm

Just a curious question. Who would the 2 pigs in the old town be purchased by? Foreign nationals working in the KSA?