Kyrgyzstan: The mountainous heart of the old Silk Road beating stronger for this old backpacking nomad

(This is the first of four blogs on last month’s three-week trip through Central Asia)

KARAKOL, Kyrgyzstan — I’ve had a weird fascination with former communist countries ever since I went to Hungary and Yugoslavia in 1978. Coming from knee-jerk liberal University of Oregon, where the sociology department was just to the left of Karl Marx, I spent a week in communist Hungary and came away with an inescapable conclusion.

My sociology professors had never been east of Hartford, Connecticut.

I looked in a soldier’s desperate eyes as he told me his impossible dream of opening a flower shop. I heard the frustration of factory workers spill their guts over bottles of vodka. I saw how the equal standard of living Karl Marx proposed was, in actuality, one step below the poverty line.

Then I crossed the border into Yugoslavia. Here ol’ Karl would’ve been proud. The equal standard of living was more middle class. The people were satisfied and proud to call themselves communists. Yugoslavia seemed like the one country where the system actually worked, kind of like the one Yugo off the car lot that didn’t break down. .

Since the end of the Cold War, the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Soviet Union, I have made frequent trips to ex-communist countries. Most are in Europe where nearly every city has memorials to the atrocities of communism. They have tours of prisons, museums, secret police headquarters. I’ll never forget the photo in the Museum of the Occupation of Latvia in Riga of a desperately crying woman, holding her small child in front of her face, saying goodbye before a Russian soldier shot her in the head.

Europe’s former gray, prison-like capitals are now among the most glittery cities in the world. Tallinn. Ljubljana. Prague. Budapest. Communism left the house and they turned on the lights. They combine the conveniences of modern Europe with grim reminders of one of mankind’s darkest periods.

Lately I’ve been exploring more distant satellite states. Last year I went to the Republic of Georgia and found the old “Tuscany of the Soviet Union” lives up to its old billing even better. Last month, I continued east, spending three weeks touring Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan with an afternoon layover dip into Kazakhstan. Except for Kazakhstan, where I only saw the modernized, comfy, leafy former capital of Almaty, the other three are different from the ex-communist states in Europe.

This is Asia. It’s where shepherds still herd their sheep the same way as under Joseph Stalin. It’s where they have more distinguished features from neighboring countries such as Afghanistan, Iran and China. It is Islam. Yet their governments are more concerned with terrorism than the U.S.

It is also where snow-capped mountains tower over emerald lakes, where sizzling, grilled meats dot menus and travel costs are among the lowest in the world. Rooms are $15 and great meals $3. Six-hour shared taxi rides are $5. It’s also where the roads are more dangerous than the mountains, the Internet is something out of 1960s Siberia and food (How ya’ like your mutton?) can be sketchy.

It’s the old Silk Road, where Genghis Khan once laid waste and Marco Polo made famous, connecting the trade routes from China to the western edge of Asia. Central Asia is the vortex of the Silk Road. I was in the middle of it.

I came for the hiking but came away with so much more. My first stop was Kyrgyzstan. I left myself one less day than I really needed and wound up with a brutal first 24 hours. I took a red-eye from Rome to the capital of Bishkek, through Moscow and arrived at 2:50 p.m. on exactly three hours sleep. I then went straight from the Bishkek airport to a waiting car where we drove seven hours east into the Kyrgyz mountains.

Kyrgyzstan is the land that vowels forgot. But it’s more than a country few can pronounce (It’s KIRG-ah-stan). The seven-hour drive was a cultural kaleidoscope that kept my eyes open as if visiting a foreign land for the first time.

Helping me in the cultural exchange was one Aleksei “Alex” Belov, a Kyrgyzstan native of Russian-Ukraine heritage who has run Kyrgyz Nomad Travel (www.kyrgyznomad.com) for six years. I normally don’t do tours but with limited time, I needed to get into the mountains as quickly as possible. Lonely Planet wrote that Bishkek’s huge Western Bus Station, about 40 minutes from the airport, is “thoroughly confusing even for locals.” For Lonely Planet to say a bus station is confusing is like a 1960s edition of Pravda saying a particular gulag is bad.

Alex, fit as an athlete, looks younger than his 38 years and more Western in his blue jeans, black T-shirt and black ballcap. He speaks barely accented English after living in Philadelphia for a spell and traveling around the American Rockies and Alaska training as a guide. He hails from Osh, Kyrgyzstan’s second city where about 300 people were killed in 1990 when ethnic Kyrgyz and Uzbeks, in Kyrgyzstan since the 1930s, clashed over land and housing. He has seen a lot and since moving to Bishkek for college, he has seen nearly every peak of Kyrgyzstan’s beautiful collection of snow-capped mountains.

As we drove east in his four-wheel-drive Sequoia, I saw cattle grazing on the side of the highway. We passed fields of potatoes, onions, tomatoes and cucumbers. Women sold wide brooms to passersby. Wolf skins for sale hung from sides of houses. A herd of goats crossed the road.

We pulled in where a small, almond-eyed Kyrgyz boy stood behind a giant iron pot filled with huge ears of corn half submerged in hot water. For the equivalent of 25 cents I had the sweetest corn I’ve ever had.

A half hour later, Alex pulled over where a half dozen men stood on both sides of the highway waving what looked like giant celery stalks. He called one over and bought one. He peeled away the green outer skin and ate it like a carrot. I tried it. Imagine a real sour piece of celery and you have the kislichka, the vegetable indigenous to this small region of Kyrgyzstan.

The country’s shape is odd. When the Soviet Union collapsed, the borders of Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan were carved up based on ethnicity. Thus, the countries’ borders weave in and out like a complicated jigsaw puzzle. At one point in western Kyrgyzstan, you can travel about 20 miles and hit all three countries.

Due to the strange borders, Kyrgyzstan is shaped like a frog on its hind legs. Its giant eye is Lake Issyk-Kol, at 2,400 square miles the world’s second largest alpine lake after South America’s Titicaca. Issyk-Kol’s gills are the Central Tian Shan mountain range which is what we saw no more than an hour outside Bishkek.

They are long, craggy and still covered in winter snow. I’d read that the height of the hiking season is July and August but I wanted to avoid Central Asia’s suffocating summer heat and Alex assured me hiking is possible in May. While we’d be limited in elevation to under 3,000 meters, there was no limitation to the region’s spring beauty. We passed a narrow clear river snaking through a deep green gorge. With the sun out and the mountains still covered in snow, it was like being inside a very still snow dome.

But we also passed some of the ugly reminders of a nation that lost the support of a monolithic state like the Soviet Union. We passed a 10-story hotel, left unfinished for the last 30 years. We passed another long wall stretching half a kilometer with individual cabins shaped like Arabian tents. This proposed conference center has been empty for 20 years.

Alex made a point to say he didn’t want to talk politics. However, he did. He was 10 when Kyrgyzstan became the first Central Asian republic to gain independence. Unlike the European countries, which received more daily dosages of oppression than bread, Kyrgyzstan actually advanced under Soviet rule. In 1991, after the Soviet Union’s collapse, 88.7 percent voted to return the Soviet Union as a “renewed federation.” However, independence forces eventually won out. Nevertheless, in the center of Bishkek remains a statue of Vladimir Lenin.

“If the Soviet Union hadn’t come here, we’d be Afghanistan,” Alex said later, sitting in a brightly lit restaurant in Karakol, the base city for some of Kyrgyzstan’s best hiking. “They introduced us to everything: medicine, education. They built industry, infrastructure.

“Without them, we’d still be living in yurts, shitting in the back.”

***

I’ve stayed in yurts before. I spent 17 days in them in Mongolia. I preferred our accommodations: a modern two-story house run by a nice middle-aged couple where we had big rooms, modern showers and a hearty breakfast of bread, omelette, cheeses and meats.

Karakol is a pleasant, lively, spotless town lined with a lot more adventure and outdoor stores than souvenir shops. I saw no other backpackers. I felt like I was the first hiker of the season. We picked up Alex’s colleague, Kirill Mashenin, a tall, rangy 29-year-old who came along for our hike to discuss summer plans with Alex. His apartment house was in a neighborhood that may as well have a giant sign outside reading, “MADE IN THE USSR.” The brown walls were caked black with soot. Windows were broken.

Another colleague, a dark-skinned ethnic Kyrgyz, drove us in his Russian-made Vaz four-wheel drive into the heart of the Ak-Suu region. It has numerous trails that lead everywhere from deep, green valleys to 5,000-meter mountains. The prime gem of this region is Ala-Kol lake, an all-day climb to 3,560 meters where you camp the night then climb down the other side. However, the snowline remains at 3,000 meters until July, limiting us to a long steady climb to Altyn-Arashan, a base camp surrounded by towering snow-capped peaks. My first hike of the year would be memorable on a gorgeous, clear, sunny, 60-degree day.

We followed the dirt road up a gentle path along a babbling brook that shepherded us into the valley. The grasses were as emerald as Ireland. Some patches could be fairways at Augusta. All the time we walked the snow-capped peaks before us got closer.

We passed a sign reading in Kyrgyz, “Take care of nature. Forest is our home.” We saw no trash. We saw no other hikers. After about 90 minutes, a descending car stopped. It was Avtandil, a big, meaty Kyrgyz who runs the Altyn-Arashan. Kirill asked if Avtandil could take his backpack up to camp.

“You were probably hung over from last night’s party,” Avtandil said in Russian.

We crossed a crude wooden bridge over a cascading river, the white water and cool breeze coming down from the mountains was the perfect refresher on my growing layer of sweat.

After about three hours, we had reached the halfway point. We had passed exactly four hikers and two Asians on horseback. (“Our four-wheel drive,” Alex said with a smile.) That’s it. We sat on wooden benches forming a half circle by the river and ate cheese, dry biscuits and part of my ubiquitous stash of Clif Bars from the U.S.

Trails in Central Asia have no directional signs. Unlike Colorado and Central Europe, where the maze of trails sometimes looks more organized than the California freeway system, Central Asia relies on guides and guile. I have no guile. I relied on Alex to make sure I didn’t wind up in a forest eating berries for three days.

The trail grew much steeper after the break. Short, steep climbs of 100 meters were broken up by level ground. We went up steep switchbacks with views behind us of the valley and river. A huge flock of sheep engulfed us along with the cute dogs who guided them up the trail. We could see some of the 5,000-meter peaks through the tree-covered hills. After we leveled off, Kirill mumbled, “Little pass.”

“That was it?” I asked.

Alex caught up from behind.

“No,” he said. “It gets steeper this next section. But we’re almost there.”

It was steep, so steep I stopped every 100 meters to catch my breath. For the first time I felt as if I was holding us up. For the first time I felt all of my 63 years. But in about 45 minutes of sweat, we reached the apex of the pass. Down below stood a deep valley dotted with white yurts, the finish line after a 14-kilometer hike and 900-meter elevation gain to 2,600 meters. In the background stood 5,020-meter Mt. Palatka, “tent” in Russian as it looks like one of those three-sided tents. It took my breath away. My smile broadened, my hopes were met.

This is why I came to Kyrgyzstan.

We descended toward camp as an eagle flew overhead, heralding our arrival. We walked right past the empty yurts where a Kyrgyz was chopping wood.

“We’re not staying there,” Alex said. “We have our own shelters. Yurts are freezing without heaters.”

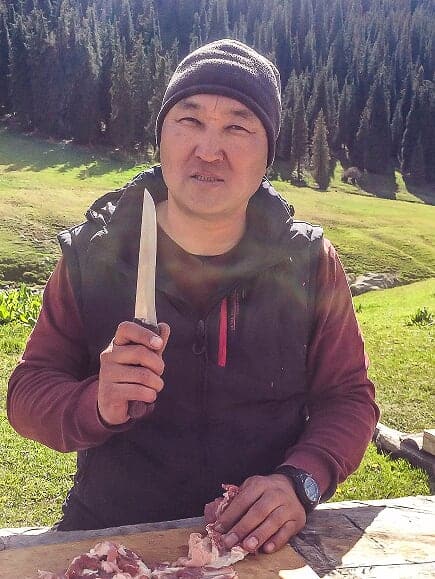

I had my own longhouse with five hard twin beds, covered in a thick decorative blanket. Before dinner I walked to the back of the longhouse where Avtandil was cutting huge buckets of mutton meat. It looked like after waste from an obesity clinic. It was big blogs of white and pink flesh — mostly white from all the fat. He took one big handful of white goo and slapped it on the table. He hit his ass and said “sheep.” We’re going to eat sheep ass?

Mutton is the Elephant Man of the meat family. It is gross and disgusting and has no taste. I ate it nearly every day in Mongolia. That was 2011 and I’m still picking out bits of fat from my teeth.

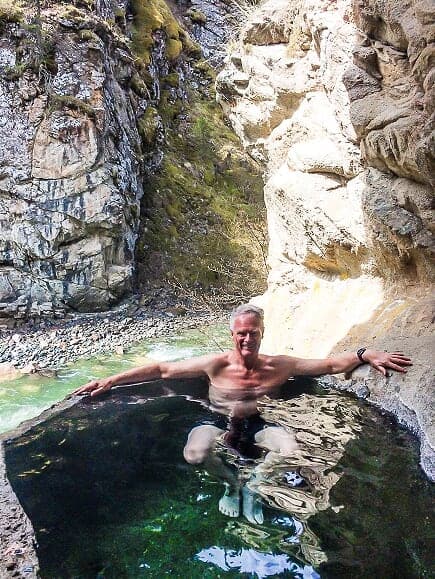

This guesthouse is special, however. It has five indoor thermal baths. They’re crude. The outside looks like the worst Third World outhouse. Inside is a gray concrete pool filled with steaming water. It didn’t have the sulphuric smell of rotten eggs, thank God. The pool was steaming hot. So hot, I had to ease my body in, splashing hot water on bare skin to get used to it. I finally settled against the back wall and let the near boiling water massage my surprisingly sore legs. I stayed in only about 10 minutes. Every time I moved a limb burned.

But it made for a nice pre-nap. The jet lag had caught up to me and I slept for an hour before a dinner I should’ve slept through. We had mutton soup. The meat wasn’t all fat but every bite took 15 minutes to chew small enough where I wouldn’t get lodged in my throat. Choking to death in a country no one can pronounce did not sound good on a tombstone. I ate the carrots and vegetables and ate only half the meat.

I went to bed in pitch blackness. the lone sound coming from the river below. Also, I thought I heard an eagle squawk.

***

The next morning on the hike back down I had one of those quintessential traveler’s moments when everything seems aligned in the world, in a combination of bliss, nature and pure unadulterated luck.

I had a thermal bath and an eagle flew by.

It wasn’t like a total eclipse of the sun. Eagles and hot springs are all over the Altyn-Arashan area. But to have it happen at the same time became one of the most remarkable experiences in my 41 years traveling overseas.

We left camp at 10:30 in a slight mist with a cold breeze coming down from the mountains. We quickly cut off the trail and headed down a steep path toward the Ak-Suu river. At the end, about 30 feet above the river, a stone semicircle jutted out from the cliff. It was filled with hot, soothing water. Alex and I walked a little farther and set back inside the rocks was another bigger one, big enough for a family of four.

I peeled off my jogging suit to the swimsuit I strategically wore and dipped in. It wasn’t as painfully hot as the guesthouse’s. It was the perfect, soothing temperature. I sat back against the smooth rock wall and looked down at the river.

When Alex joined Karill in a planning session, I saw it. An eagle, with about a four-foot wingspan, soared by me almost at eye level. It was in no hurry. It probably didn’t even know where it was going. Like us, it was probably just out for a little cruise. But it went slow enough where I could see its eye. And then something remarkable happened.

It looked at me.

I swear, it turned its big head and his right eye looked at me. I should’ve winked or nodded or done some human gesture as an act of saying, Yes, I acknowledge you and respect you and will do you no harm. What I wanted to express is this:

In a world of chaos, folks, don’t underestimate Mother Nature’s little ironies.

***

After hiking 28 kilometers over the previous two days, I didn’t protest the next morning about driving into Karakol Valley, another 14-kilometer journey. Then I saw the road we drove over and thought hiking would’ve been easier.

This was simply the worst road I’ve ever been on, worse than the mud flats that entrapped our huge big-wheel people mover truck in Tanzania. Worse than the unpaved, unmarked roads in the Mongolian steppe.

This road was downright scary.

k

On the way out of Karakol we passed what looked like a factory abandoned by the Soviets in the ‘60s. It was a crumbling edifice with peeling paint and beat-up brick. It’s actually the heating facility still used in Karakol in the winter.

About 30 minutes south of town we passed a crude gate into the national park. The road was gravel and dirt, similar to the trek to Altyn-Arashan. No problem. I sat back and enjoyed being a lazy passenger listening to Top 40 hits on the radio.

Then the gravel got bigger. Soon they were big rocks. Eventually, the road became a sea of boulders, some of them three feet high. How in the hell would they fit under the chassis? Alex had to slow to a crawl to strategize his way around the rock traffic. Going no more than 2-3 kph, he managed to guide through his remarkable four-wheel drive Sequoia which now goes into my lexicon with man’s greatest invention alongside fire.

It got worse. When the road turned to dirt, we faced giant mud rivets two-feet deep. One false move and we’d be stuck. We saw no other people except two Polish backpackers near the gate.

“See how far we’ve developed Kyrgyzstan since the collapse Soviet Union?” Alex said sarcastically as he maneuvered the car through the dirt maze.

It went on like this for two or three hours. A sea of rocks followed by huge divots on a dirt road so narrow we couldn’t turn around. We’d have to go backwards all the way back to Karakol. If Genghis Khan tried to pass this way, his horses would’ve bucked him off. Marco Polo would’ve taken one look at it and said, “Fuck it! Let’s go back to Venice!”

I seriously wondered about food and water. I wasn’t told about Karakol Valley’s facilities so I brought one lone Clif Bar. I drank most of my water in town. I saw a dead pony along the side of the road. I wondered what baby horse tasted like.

However, the effort was worth it. We reached the valley, which is a gigantic bowl surrounded by Peak Karakol and the Ayu-Tor and Jeti Oguz gorges. To my right were two big mountains. The saddle between was the gateway to Ala-Kol lake, totally covered in ice and snow until late June. The grounds were beautiful. A huge expanse of green grass that could be a before picture of a golf course. Narrow pine trees pin pricked the hills. A small river flowed through it. The only other people we saw was a Jeep of Kyrgyz surveying the area.

We sat by an old, rickety wooden bridge and snacked on sweet ringed biscuits, mini Twix bars and freeze-dried peanut butter Karill brought. It was a nice day with temperature about 50 degrees.

Before we left we passed the Poles who were hiking to the base camp and then going to lake Ala-Kol and returning. I told Alex I thought you couldn’t go there in May.

“You can but I wouldn’t risk it,” he said, shaking his head. “By the lake are cliffs of snow and ice. You need more equipment than what we’ve got.”

Back in Karakol for the night, Alex took me to Dastorkon, a typical Kyrgyz restaurant with a menu the size of Denny’s. It had a whole page just for kabobs (called “shashlyks” here) and lagman, these thick Kyrgyz-style noodles about twice as long as Italian spaghetti. It was still Ramadan and we ate at 6 p.m. Sunset, and the end of the Islamic daily fast, wouldn’t occur for another two hours. Thus, we were the only people there.

On the way back to the guesthouse we stopped at a little store on the way back and picked up a bottle of Atalyk, wine from this area for all of 214 som (less than $3). We sat in the guest house kitchen and drank the whole bottle.

Alex told me the new Silk Road is still a freeway for drugs. And marijuana grows all along it. Yet if you get caught with a joint it’s years in prison.

Islam is growing here, too. “They’re building more mosques than schools,” he said. Many rural communities have put pressure on little stores like the one we visited and tried getting them to stop selling alcohol. Some buy every bottle on the shelves and then destroy them in front of the other villagers.

I also noticed something on the guest house’s refrigerator: a photo of Joseph Stalin, Lenin’s successor. Alex said many people in Central Asia still believe in the guy.

“But he was as bad as Hitler,” I said.

“They were two totally different ideals,” he said. “Hitler wanted to destroy every ethnic group and make the entire world aryan. Stalin was putting down uprisings to keep the system working.”

“He killed 60 million people,” I said.

“How many American Indians did you guys kill?” he said.

Touche.

***

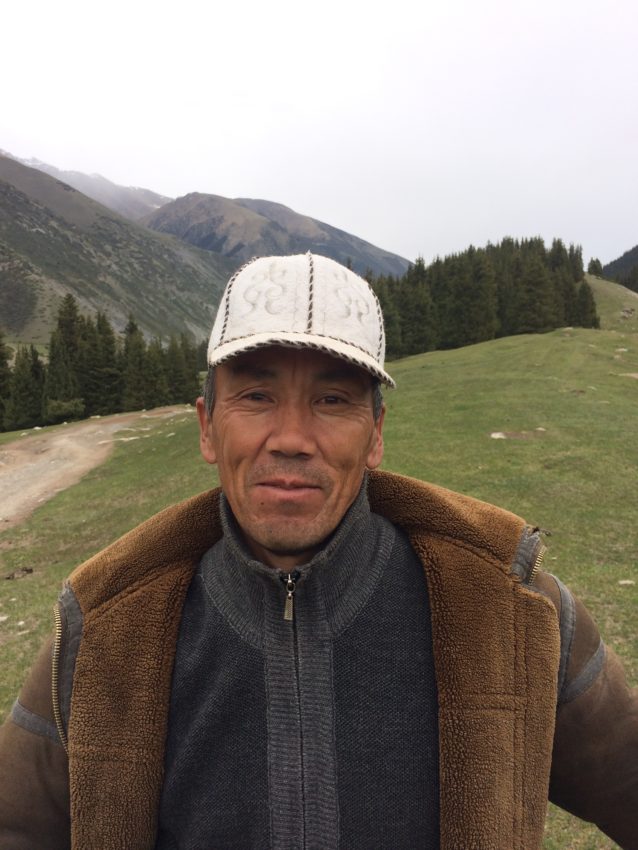

The next day I met a wonderful local. It was one of those meetings that gets a red star in your notes and a lead in your journal. He was a shepherd named Taalaibek and one of about six people we saw during a three-hour drive through the beautiful, expansive Georgievka and Semenovka gorges. He was small, about 5-foot-6, with a smooth, deeply tanned face, Kyrgyz eyes and a mouthful of gold-capped teeth. He wore a decorative white ball cap and an expensive, heavy jacket over a gray turtleneck. Some friends had dropped him off from the village of Ak-Suu down below to tend to his animals. They’d gone farther up and he asked Alex for a ride back.

We were in the middle of this massive valley staring out at a very cold- looking lake with some of the snowy Kaungey Ala-Too mountains above it. My first overcast day hid most of them but the beautiful, expansive gorges and our encounter made up for it.

He was a bright, funny, interesting guy. I asked for a photo and he said, “Why do you want my photo? I’m just a simple shepherd.”

I asked him how his life as a shepherd has changed since the fall of the USSR.

“It was a collective system,” he said in Russian through Alex. “On the one hand it’s better opportunities. You can develop and grow. And all have the equal opportunities. In Soviet times there were limitations. You could have five sheep and one cow. You couldn’t have a horse. Horses were collective.

“It was different times. Everything was equal. Now it’s more business relationships which isn’t good sometimes. People are just concerned with their own income.”

I asked the ubiquitous question, “What do you think of Donald Trump?” He had a pained expression?

“I don’t pay attention to what our president is doing,” he said. “I don’t give a shit about Donald Trump.”

In the three years I’ve asked that question, from the bars of Iceland to the Buddhist temples of Laos, that’s by far the most positive thing I’ve ever heard a foreigner say about our Mango Mussolini.

We made our slow return to Bishkek via the north shore of Issyk-Kol. We passed small towns lined with small stores with people mingling on street corners. Everyone was out in pleasant 60-degree weather.

Our breakfast had barely been digested before Alexei turned off the main road and up a dirt road to a fish farm. We went back behind a building and saw 17 pools, half of them filled with orange and brown-tinted fish, swimming around like koi. Alexei said there were no fishing limitations on the lake. Despite being the second-biggest alpine lake in the world, it nearly ran out of fish. About six years ago they instituted a fishing ban which explained why I never saw a boat anywhere on the lake, not even docked. At the same time they started fish farms such as this one.

Alex greeted the pretty cook and took me to one of the pools.

“Do you want golden trout or rainbow trout?” he asked.

Golden trout is a real delicacy in Kyrgyzstan and the most expensive thing on any Bishkek menu. The restaurants all get their fish here.

A skinny man with a ball cap took a net to one of the pools and splashed the top of the water. Fish came swimming and instead of getting food one got caught. He picked it up, put in a dry bin and I watched it drown on the surface. Being a meat eater and wildlife lover has its conflicts. This was one of them. When the man took a lead pipe and cracked the skulls of four fish Alexei ordered, I turned away.

But I quickly forgot my humanitarianism when the man brought out the fish. It was 1.2 kilos, butterflied and covering an entire plate. Even though flattened, the meat was thick, juicy with few bones. We devoured the entire thing. After I patted my belly, I realize the $20 pricetag, split between us, was a real bargain.

We spent the night in Cholpon-Ata, a lakeside resort town that every summer is teeming with the Bishkek rich and the Russian and Kazakh glitterati. The Panorama Hotel is spectacular. My room was huge, the size of my Rome living room with big windows and a balcony looking out over the lake. Issyk-Kol looks like a mild ocean. I could not see land on the other side. It was gray-blue, looking as cold as a melted glacier.

We had another fantastic meal. My opinion of Kyrgyz food skyrocketed since the shorpa (mutton soup) in Altyn-Arashan. I had this terrific “hunting salad” made up of beef, cheese, tomatoes, croutons a little mayonnaise. My chicken kabor, six big, juicy chunks of grilled chicken, melted in my mouth.

We were at Barashek (ship in Russian), one of the few Cholpon-Ata restaurants open year round. It’s big with white tablecloths and overstuffed chairs. Two disco balls over a dance floor gave it a Beijing feel to it. When we entered at about 8 p.m. most of the tables were filled with food on plates but no one ate. Islamic prayer played loud over a speaker. I thought an iman was praying somewhere.

When the sun finally set a little past 8, everyone starting eating. No wonder the three kids at the table next to us were crying. Soon a singer sang Russian pop tunes and all the Kyrgyz women got up to dance, nearly all wearing tennis shoes.

***

The next night it was time to say a grateful goodbye to Alex, a truly great guide, when he dropped me off at an apartment in Bishkek. Kyrgyzstan’s capital doesn’t have the glitter of other ex-communist capitals but it definitely has the memories of 73 years under Soviet rule. The main street Chuy prospektesi is lined with massive old Soviet buildings with giant flagpoles. Ala-Too Square is the epicenter of Bishkek and where you can still see goose stepping soldiers change guard.

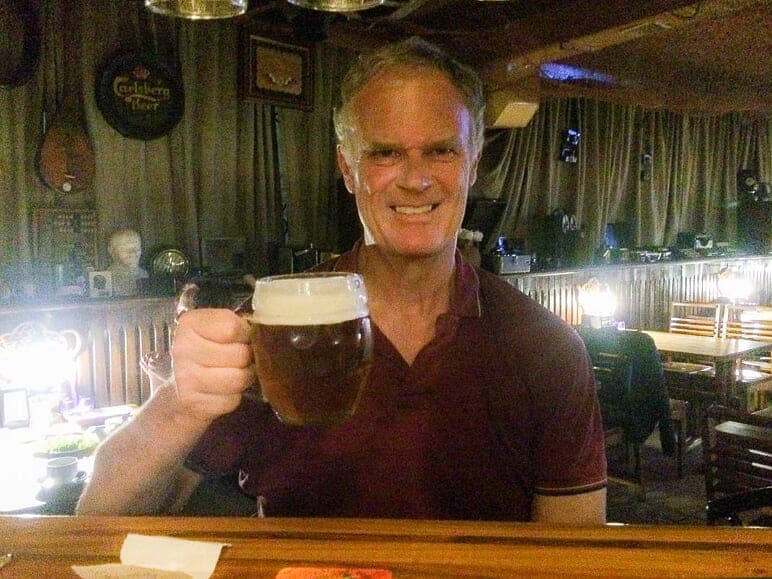

Instead of sightseeing, I spent an hour looking for Staryy Edgar, an old Bishkek watering hole hidden inside a leafy park along Chuy. It’s dark, tiny and kind of romantic with a dingy, Soviet feel to it. Fishing nets hung from the ceiling, A model boat hung on the wall. The only other people were three local girls dining on what looked like pretty good food. I ordered a beer simply labeled, in a throwback to old Soviet marketing, “Kyrgyz.” I paid all of $1.80 to a young, crew-cut Russian bartender who spoke no English. At about 7, a tall, suave Russian man in a black suit crooned Russian pop songs to the four of us with nothing else to do.

Thanks to Mother Nature, Kyrgyzstan has plenty to sing about.

June 11, 2019 @ 2:49 pm

I’ve been many times in the -Stans and while Kazakhstan has been my first love and Murghab, Tajikistan my fav village, I can’t stop feeling a strong attachment to Kyrgyzstan. Some great people, incredible scenery and fabulous memories of the Pamirs and of the World Nomad Games. I’m coming back in less than a

Month!

September 23, 2020 @ 8:01 am

Awesome Article! very intresting and informative. Thanks for sharing.

https://www.himalayanadventuretreks.com