Ljubljana another Eastern European gem of a capital even a dragon could love

LJUBLIANA, Slovenia — What is it about these former communist capitals in Europe that makes me want to hug them so much? Ljubljana is so cute it belongs on a cat calendar. Its old town is a compact, cobblestone neighborhood with high-steepled churches opening up to big squares. Running through it is the Ljubljanica River lined with outdoor bars and restaurants serving those fantastically underrated Slovene wines. Looking down at it all like a kindly grandfather is the 15th century Ljubljana Castle, partially hidden by a forest of trees that climb all the way up Castle Hill.

Ljubljana. Bratislava. Prague. Tallinn. Riga. Vilnius. Only 25 years ago these were centers of suppression and depression. Today they glitter like candles on a birthday cake. They have plenty to celebrate. Democracy is kind of a cool thing when compared to living behind the prison of an Iron Curtain, where you can’t say you don’t like the Iron Curtain. Slovenia’s economy is in the tank, like much of Europe, but I don’t see anyone getting thrown in jail for gathering on street corners with other intellectuals.

It’s like communism left town and someone turned on the lights. I was in Budapest in 1978. Since citizens of Iron Curtain countries could not go beyond the Iron Curtain, Budapest was seen as the de facto party center for all of Eastern Europe. Hungary’s famed Egri Bikaver (Bull’s Blood) wine flowed all night and the Danube River added a majestic touch but the place was dark, foreboding. The giant statue of the woman holding the hammer atop Buda Castle seemed more executioner than historic symbol. I returned to Budapest in 1990, a year after independence, and everything seemed to have a fresh coat of paint. They changed the light bulbs. Everything in Budapest seemed to dance.

Ljubljana made me want to dance — and I hate to dance. But I found myself tapping my foot to a tune in my heart as I looked out the eighth-floor window of my AirBnB in the heart of Ljubljana. Just a few blocks away were the steeples of churches in the old town. To my left just above eye level was the castle, Slovenia’s white, blue and red flag flying in the soft breeze. Below me was a narrow pedestrian street with boutique shops, cheap, casual restaurants and funky local bars. A cross-section of Slovenes in coats and ties, tattoos and dirty overalls gathered on the street with big steins of cold beer. The only thing obstructing the view was the apartment building next door, a tall, rundown eyesore of communist-era architecture that could pass for any 1960s socialized public housing from Prague to Vladivostok.

But this is what I love about the old Eastern Europe. (By the way, Slovenes HATE being called Eastern Europeans. They say they’re now Central Europeans. Sorry, folks. Your communist legacy still defines you.) The mix of East and West is fascinating. You see a crumbling, charmless, concrete block of an apartment building next to an upscale wine bar. You talk to a guy in his 30s about his vacation to Sri Lanka at one table and at the next table you talk to a guy in his 50s about standing in line to buy apples when he was a kid. You can’t get that range of lifestyles anywhere else in the world. I adore Eastern Europe.

Of course, the booze is good. On a cool, overcast evening, I sat down by the river where all the bars seem to run together. Young, cute waitresses who never stood in line to buy anything but iPhones flitted around with big glasses of Slovenia’s long list of local beers. A pretty blonde named Yetna served me a crisp white wine called Refosk which seemed to summarize my feelings about this city. Clean, cool, refreshing. Even in Rome the graffiti gets to me after a while. In Paris it’s the noise. In London it’s the larcenously priced subway. But Ljubljana seems like such a happy place. All the yuppies around me laughed, chatted, hugged, kissed, smiled and drank. They seemed oblivious to an economy that has gone from one of the best in Eastern Europe to among the struggling with the rest of the continent. They reminded me of Romans in 2003 before 12 years of runaway inflation with the euro reduced them to bitter, angry quasi peasants.

Looking over my shoulder from down the river stood Ljubljana’s charming town symbol. It’s a dragon, two of which lord over both sides of Dragon Bridge. According to legend, a giant dragon watched over the city. Apparently, it did nothing but drink mead while Ljubljana was being sacked by groups of savages who practically took numbers waiting their turn. Huns, Ostrogoths, Lombards. Then St. George, the patron saint of the castle chapel, slayed the dragon who still has a spot in Slovenes’ hearts — not to mention on nearly every souvenir you find in town.

I’m partial to cities with castles. Not only are they constant reminders of a city’s — and nation’s — history but they provide spectacular views and great picnic grounds. The Ljubljana Castle is one of the best in the world. It’s an easy, tree-lined climb up narrow cobblestone paths from the old town. Once on top, I walked along the ramparts and saw a panoramic view of a city lined with red-tiled rooftops, a regular feature all along the west coast of old Yugoslavia. To the left was a deep wooded area that fell all the way to the river below. A cool breeze came in from the rolling green hills beyond. The sun was on my face. I felt, not at all oddly, like a king.

A film clip inside the castle told me that people have been doing what I did since the 13th century B.C. That’s the dates of ruins from habitations that were found on the side of this very hill. The Celts lived here in the 9th century B.C., then came the Romans who built a fort and stayed 400 years. The Romans hadn’t packed up their last cappuccino machine when Attila the Hun raped, pillaged and plundered in the 5th century and the Slavs ran amok in the 9th century. The castle went up in 1456 to protect them from the Turks and it’s still standing today.

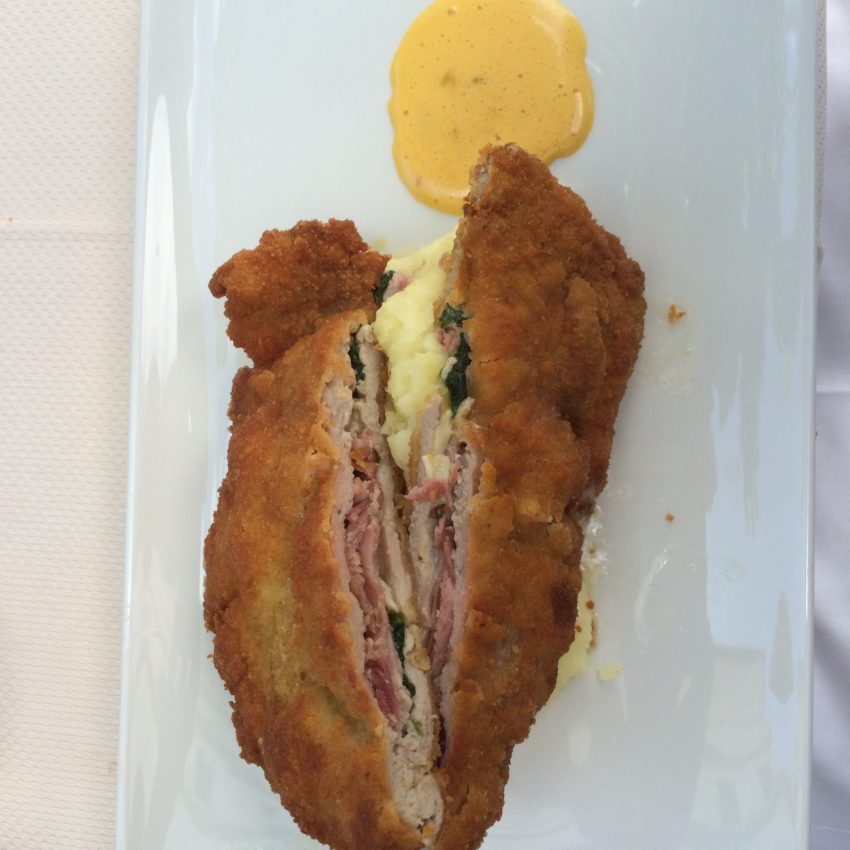

What is new is the restaurant in the castle grounds. At least, I don’t think old Attila ate thin slices of pork filled with grated cheese and spinach and fried in almonds with mashed potatoes. That’s what I had at Gostilna na Gradu. He may have drank a few bottles of the Rebula red wine with which I washed it down but he may have drank Slovene blood instead.

Ljubljana’s restaurant scene, like the rest of Eastern Europe (In 1985 there were an estimated 50 restaurants in Moscow; today there are more than 3,000.), has exploded. In the university area north of old town, a restaurant called Eksperiment is an example of the growth. In the ‘80s, there was one cafe or restaurant on the narrow street. Today, they’re all up and down the street where Eksperiment replaced what was a casino. It has modern wooden tables and a shiny back-lit bar with wines from across Slovenia and Europe. Slovene cuisine is real heavy. Lots of grilled meats. Order a mixed grill plate of sausage, turkey, sirloin and chicken and you have enough protein for the New England Patriots. Any vegetarians are turned back at the border. I went relatively light with a Pleskavica, a ground beef patty stuffed with mozzarella.

In light of this easily toured and sparkling clean city, it’s hard to imagine the blood that has spilled in Slovenia. I couldn’t pick up a hint while strolling through the city’s museums, tony restaurants and romantic, dimly lit side streets at night. The whole place feels like the USSR leveled it in the ‘80s, collapsed and Slovenia rebuilt its capital on the model of Disney World. Since independence, Slovenia managed to avoid much of the Balkan bloodshed that made so much news in the ‘90s. I toured Ljubljana’s terrific city museum which breaks down the country and its capital from prehistoric times. One highlight of the museum is standing on the floor is a Ficko, Yugoslavia’s equivalent of the Soviet Union’s Lada. The Ficko was the forerunner of the Yugo which was laughed at all over the world, even in countries that didn’t have cars. The Ficko is a little bigger than one of the mini cars those fez-capped Shriners ride around and its panel didn’t even appear to have a radio.

What I found interesting from the history is after a couple millenniums of war, Slovenia has had a relatively peaceful existence since independence. While Serbia ran roughshod over Bosnia and Kosovo and fought the Croatians in a four-year grudge match for Croatian independence, which still rankles folks on both sides of the border, Slovenes sat in the corner of the old Yugoslavian republic and sipped wine. Well, in the summer of ‘91 the Yugoslavian army marched on Slovenia when it quit the Yugoslav Federation but the war lasted all of 10 days. Sixty-six people died but it has been uphill almost ever since.

Slovenia always was the richest of the Yugoslav republics. In 2007 Slovenia became the first of the 10 new European Union states to adopt the euro and experienced an annual economic growth of 7 percent. Like most successful countries rebounding from economic hardship, they banked heavy on tourism. They promoted a country that’s 58 percent covered by forest, the third most in the EU. It promoted its inexpensive and exotic ski resorts in the east, a promotion more than aided by sexy Tiny Maze winning two gold medals in the Sochi Olympics. And, what brought me to Slovenia, the wines, have become huge draws.

It’s a mess today. The global economic collapse in 2008-09 sent it heavily into debt from which it is not close to emerging. Unemployment is nearly 13 percent.

However, I don’t live here. I don’t work here. But I sure love visiting here. I can see why that dragon stuck around so long.

June 18, 2015 @ 8:42 am

Jeff and I traveled to Slovenia in September. So beautiful. I hope you’re heading to Croatia. There’s a lot of great places to visit there.