Madain Saleh: Saudi Arabia’s 2,000-year-old UNESCO Heritage Site and sister city of Petra

Tough to reach but Madain Saleh is worth some days in the desert

(This is the last of a three-blog series on my travels through Saudi Arabia.)

AL-ULA, Saudi Arabia — If you look at my tent from the right angle, my home for the next three days could pass for a Bedouin nomad’s. It is big, square and white as a sheikh’s robe. It’s a scimitar throw from a grove of palm trees, all glistening in the sun with sheer mountains of red rocks rising in the high desert beyond.

But where is my camel? Nowhere. Parked next to my tent is a Chevrolet Spark. It’s the car I rented to explore one of the few famous tourist sites in a country in the infancy of tourism.

I have decamped at Rural tents Naseem Alouzaib, a collection of comfortable tents 12 miles north of Al-Ula. A town of about 32,000, Al-Ula is Arabic for “In the middle of nowhere.” To me, an intrepid traveler running out of places off the beaten path, this adds to the intrigue. Al-Ula is in northwest Saudi Arabia, 25 miles northwest of Medina, next to Mecca Arabia’s holiest city; 145 miles east of the Red Sea; 410 miles north of Jeddah, Arabia’s cosmopolitan jewel; and 630 miles west of Riyadh, the capital.

Al-Ula is the jump off point to Madain Saleh, the second city in the Nabataean Kingdom from 2,000 years ago and Saudi Arabia’s first UNESCO World Heritage Site from 2008. It’s the sister city of Petra, Nabataea’s better-known capital 310 miles northwest in Jordan. Petra has attracted people since 7,000 B.C. Madain Saleh has attracted them mainly for about nine months or about the time the Saudi Arabian government finally started issuing tourist visas.

While I researched Saudi Arabia, numerous sources said there is no reason to come if you don’t see Madain Saleh. It’s like visiting Egypt and not seeing the Pyramids.

Al-Ula is one of the few towns in the middle of a desert but at 2,800 feet it has all the raw beauty of Saudi Arabia’s Empty Quarter in the south without the skin-searing heat. And today, in February, it’s downright cold.

For 10 days in Saudi Arabia I lugged around a black leather jacket, looping it over my shoulder as I went from airport to taxi, taxi to hotel, hotel to airport in highs of about 80. Finally I have it on, huddling in my tent as the sun sets and the temperature drops like I cold rainstorm. The Bedouins roughed it more than I. My tent has two twin beds surrounding a big electric heater. I’m writing this under a thick comforter with another in a plastic case at the foot of the bed.

After the urban sprawl of Riyadh and the seaside chic of Jeddah, Al-Ula seems like the back of beyond. The people are few. The roads are empty. But 2,000 years ago, this area was one of the most important in the Middle East.

The Nabataeans helped fuel the trade routes between the southern Persian Gulf and North Africa. They had one of the most sophisticated water systems in history and an educated, open-minded population famous for their artistry and elaborate tombs, all still on display today. Madain Saleh, considered the “Capital of Monuments” among Saudi Arabia’s 4,000 archeological sites, remains one of the great urbanization stories in man’s history.

That is why I am here. That and to sleep in a tent in the middle of the Arabian desert .

How to get there

Getting from Jeddah to Al-Ula exposes some of the rough edges of Arabian tourism. There are only three direct flights a week from Jeddah. If you don’t want to arrive on one of those two days — as I do not — I leave Jeddah at the ungodly hour of 2:20 a.m., land in Riyadh at 4 a.m., try to stay awake for three hours then take a 7 a.m. flight west to Al-Ula at 8:45 a.m. That’s 6 hours, 25 minutes to fly 400 miles.

Arriving at Al-Ula’s small, sparkling clean airport, the car rental company’s promise of a representative with my name on a board never materializes. Besides bringing back nasty flashbacks of getting stood up in airports by various women, it left me with no car in an area with no mass transit. In the middle of the Arabian desert, a woman was the last thing on my mind.

A couple of crisp text messages to a Riyadh travel agent and the rental company produce nothing. After an hour watching a line not move in front of the lone car rental desk, which isn’t my company, the rental company finally reaches me with a voice message.

“He’s at the counter,” he says.

After another hour, I finally reach the desk and the man adds to my impression of these wonderfully friendly Saudi people. He profusely apologizes.

“I’m so sorry for the wait,” he says, holding his hands out in exasperation. “This computer is so slow.”

He gives the car to me for two days even though I’ll return it about three hours after the second-day deadline. He says he’ll pro rate it, something I never experienced in the U.S. Saudi Tourism 1, U.S. Tourism 0.

Beautiful drive

A few factors make driving in Saudi Arabia wonderful: 1, the gas, obviously in a country with the highest oil reserves in the world, is cheaper than water. I paid 75 cents a gallon. For three-quarters of a tank to get me through three days, I paid only 10 euros; 2, the roads are beautiful. They’re like freeways in Switzerland. Everything is freshly paved. It looks like they started tourist visas at the same time they painted over the roads. I don’t see a single bump, rock or piece of garbage on the side; 3, there’s hardly any traffic. Up here, in Northern Arabia, there are more Bedouin nomads than people. I don’t remember seeing more than 10 cars.

Along the way is like driving over the moon. Big craggy mountains of red, brown, gold and beige are on both sides of me. Vast valleys of sand lay between. The sun is out. The sky is as blue as the South Pacific. It’s like being on another planet with the cleanest air in the galaxy.

After about an hour, my GPS leads me off the highway, down a dirt road, down another small paved road then along more dirt. This is off roading Arabian style and I speed up to make sure I don’t get stuck in the sand. I finally weave my way down a paved country road and through the Rural tents’ fence where a small, young man in a crude headscarf directs me to my parking spot. It’s in a gravel lot next to four big white tents. He pulls the big cloth door aside and after one hour sleep all night and driving for another hour, my lodging could pass for a harem. But exhaustion and hunger devours any other human need.

I ask about food.

“No eat here,” he says with a smile. “Only sleep.”

He hands me a plastic menu with pictures of various shish kabobs and Arabic lettering. He says they deliver. Fine. I eat a Clif Bar for lunch and sleep for what I think will be a thousand Arabian nights.

A night on the town

I wake up to some American English chatter outside. I go out to a sunny but chilly afternoon and see two young men talking to the guy in the headscarf. We exchange pleasantries and I recognize them as two others at the airport nearly nodding off waiting for rental cars that morning. Justin, 40, works in California’s tech industry and Minh, who moved with his family from Vietnam to California when he was 4, is a counselor at University of California-Davis. Both live in Sacramento and resigned their jobs to travel the world. They’ve gone from Europe across Russia down through Mongolia, into Southeast Asia then to the Middle East. Five years ago they traveled for 14 months. Since before they were born, I’ve traveled to 107 countries. They’ve already been to 99.

The host gives them the address of the restaurant that delivers and they ask if I’d join them. Being tech wizes, they had all kinds of charger adapters they loaned me and had the best GPS on the market. In the middle of Northern Saudi Arabia, that’s as needed as extra water. But the problem with GPS is not every establishment exists on the radar, especially in the middle of an Arabian desert. This restaurant, called Sultana, is barely listed in the neighborhood. We see a red dot without a name in the area and we take off down dark, dirt roads with occasional patches of pavement. We come to what should be the restaurant. It’s someone’s home.

A tall, young, heavy-set man in a gray thobe comes out and introduces himself as Michel. Minh shows him the GPS. He agrees to take us. We pull up to this small, rough-and-tumble place with a wood oven where four guys in facemasks grill different meats and the short manager takes our orders behind the counter. This couldn’t be more local if we shared the table with goats.

We order the mixed grill: a huge plate the size of a symbol covered in rice then topped with sizable links of lamb, chicken and beef. It comes with sides of flatbread and hummus. I’m not that hungry but the meat is so tender I eat for 30 minutes.

Despite Michel not speaking a word of English, we have a lovely talk. Minh and Justin use Google Translator’s voice app to translate messages. Michel reads them, gives a delayed laugh, then says something in Arabic. We read and then laugh, always delayed.

Michel is 24 and not working. He lives with his mother. He had spent that day at a commission looking for a job, somewhat shocking since developments in Al-Ula have left it with a negative-2 percent unemployment rate as recently as December. The pandemic has crashed the oil market and the Saudi government has cut back on social subsidies but before the virus hit I see no homeless and few beggars.

For years Saudis lived in luxurious isolation. Still, unlike most Americans, Saudis seem very interested in outsiders. Everywhere I go people ask me about life in the U.S. and my life in Rome. Michel asks us what we think of Saudi Arabia and our travels. He’s interested enough to invite us back to his place for tea. He leads us through the tiny roads and dusty trails and we stop at the same place where we got lost. It’s his house.

We follow him to an open-air lounge. It has a giant red, elaborately decorated carpet with cushions. We take off our shoes but I don’t take off my coat or stocking cap. The temperature is in the low 40s.

He gives us a cup of Arabic coffee, which tastes almost as bitter as the country’s non-alcoholic beer, and Arabic tea which is sweet, hot and smooth. He passes around a tray of dates of which I’m beginning to grow quite fond. It seems raisins taste much better when they’re on steroids.

We talk via Google Translate and joke about how his mom may get upset at him bringing home three strangers. Soon his uncle comes through the fence. He’s right out of central casting. His big pot belly stretches his gray thobe and his white keffiyeh and salt-and-pepper beard make him look like one of Ali Baba’s 40 thieves. Michel said he likes playing soccer and has lived in this village his whole life. His uncle has walked this desert for more than 60 years.

I secretly hope lifestyles like Michel’s and his uncle’s remain. Under Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman, as I wrote three weeks ago, Saudi Arabia is changing as fast as any country in the world. His quest to diversify the economy away from oil has resulted in looser visa restrictions, more freedom for women, new roads and hotels and refurbished attractions. It’s all part of his Vision 2030, his quest to get 100 million visitors by 2030. If this coronavirus ever dies (Saudi Arabia has had 136,000 cases and 1,000 deaths compared to 2.2 million and 119,000 in the U.S., respectively) and Saudi Arabia gets its oil industry back on track, maybe Michel won’t have to spend a day at a commission looking for a job that isn’t there.

Maybe he’ll find one at the place I came here to see.

The Madain Saleh site

After 11 days I finally find a tourist center in Saudi Arabia. Madain Saleh is hardly a tourist trap. Tourist traps get more than 11 tourists on a tour bus to see the remarkable remnants of a 2,000-year-old civilization, freshly refurbished this year. About 1,300 years before Marco Polo, there were the Nabataeans. Until conquered by Trajan and the Romans in 106 A.D., the Nabataeans ran the trade route in the Middle East. They were wealthy, ingenious with water and built some of the most elaborate tombs in history. Writer and photographer Jane Taylor, who wrote, “Petra and the Lost Kingdom of the Nabataeans,” called them “one of the most gifted peoples of the ancient world.”

With Saudi still in its tourism infancy, Madain Saleh’s setup is a little strange. To buy my ticket I must drive to a place oddly called Winter Park. It’s a giant parking lot in a valley framed by massive, craggy, red mountains. It’s like in the bed of an enormous Grand Canyon. It’s a rock climber’s and photographer’s paradise and the weather is perfect: sunny, clear and in the 60s.

It’s in an open field littered with popup fast food places such as Dunkin Donuts, Burger King, Dairy Queen and Arabia’s most famous fast-food joint, Al Baik. I go to a steep A-frame ticket counter and a pretty black woman in a long kaftan sells me a ticket for 255 riyals, about 65 euros. I walk onto the nearby bus and see only two other people, a Hungarian couple camping on beaches around Arabia. Soon eight more join us: a well-traveled Finn and his Spanish friend motorbiking all over the world, a Jordanian, and five guys from the same Vueling flight crew. All of us are well-traveled. All of us are respectful. Finally I’m with my own kind.

A 30-minute bus ride takes us to an old train station where the original locomotive holds fake boxcars, replicas of the ones that ran from Damascus to Medina in 1900. Before, it took pilgrims 40 days to travel the 1,300 kilometers on camels to reach Medina. The train took five. When World War I hit, Saudi Arabia supported Germany and the railroad was destroyed. Now it’s a photo op.

Our guide is Arden, a diminutive Al-Ula native who, illustrating Saudi Arabia’s start in tourism, has been a tour guide for only three months. But he is damn good, speaks excellent English and has an answer to every question.

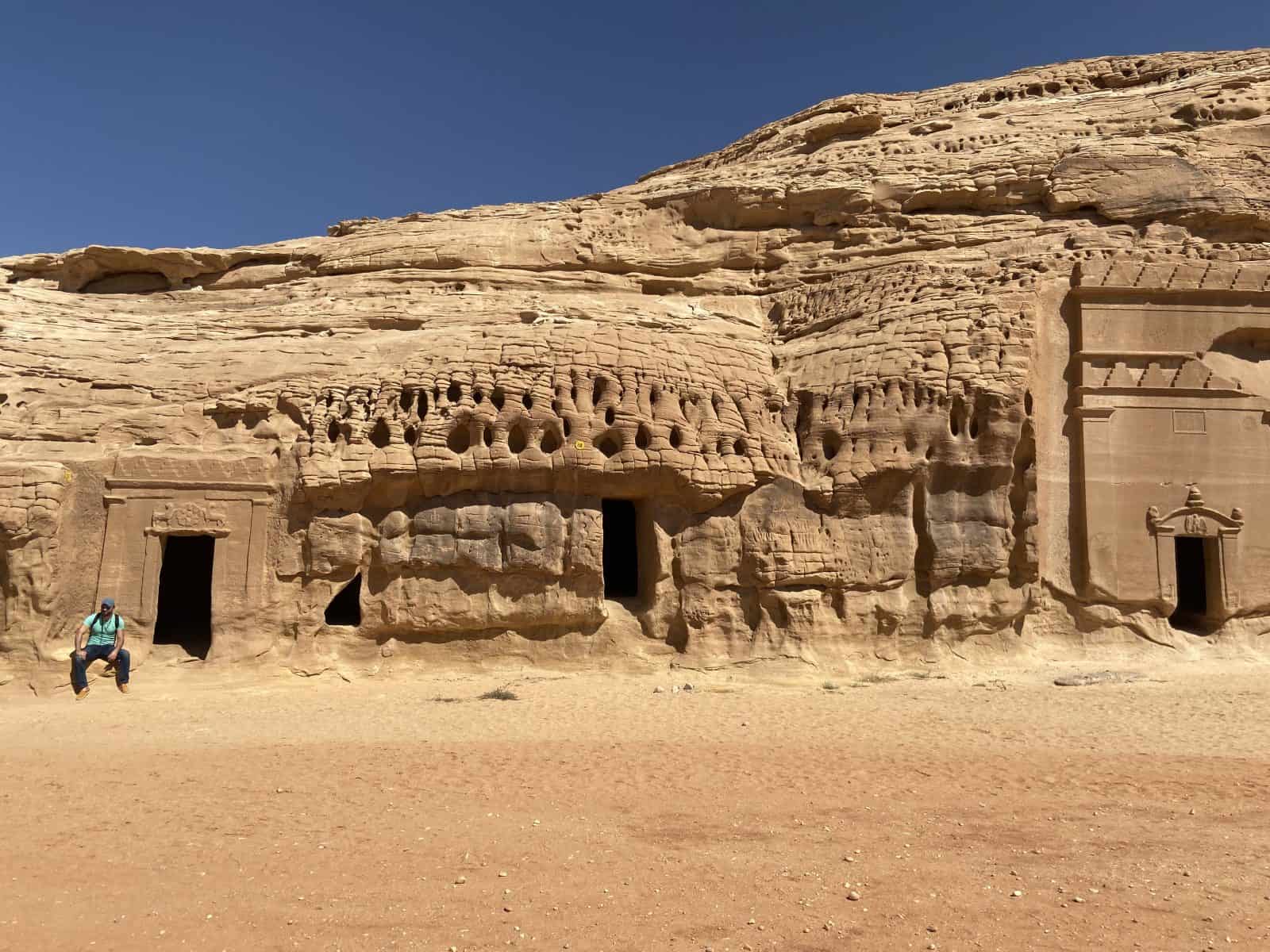

Another short bus ride takes us to a setting that in itself makes Madain Saleh worthy of the UNESCO Heritage Site. This is the mountainous desert. The Hijaz mountains of red and beige and brown and gold rise on both sides of us. Madain Saleh, called Hegra before the Muslims changed it, is a site covering eight square miles littered with towering tombs carved out of pure rock.

The Nabataeans built 131 tombs and each one seemed to try and outdo the last one. As trade merchants, they were incredibly wealthy — and smart. About 450 million years ago, an ocean covered this whole area. When the oceans receded, water was deposited under the sand. The Nabataeans carved wide grooves in the side of mountains to collect rainwater in numerous underground wells they built in the sand, hidden from intruders. The wells were made of water-proof stucco and nearly 100 feet long.

They did three things to build their civilization into one of the grandest during the time of Christ:

- Planted oranges and dates and watered their orchards for food with an elaborate water-gathering system.

- Governed the important trade route that took frankincense, myrrh and incense, used in perfumes and various ceremonies, from what is now Yemen and Oman, up north into Africa.

- Built 131 elaborate tombs, the artistry of which is remarkable to this day.

About 10,000 people lived in Madain Saleh, compared to 25,000 in Petra, and Arden explains that society was very open. Other religions were encouraged and welcomed. Women had equal status.

One Spaniard quips, “What happened?”

Arden even laughs.

The preservation is remarkable. The carvings can be seen without a powerful camera lens. The walls look sturdy enough to last until the end of time. One big reason is superstition. The Thamudis, an ancient Arabic people, settled this area in the 8th century B.C. According to Islamic texts, Allah punished them for idol worshipping and battered the area with an earthquake and lightning strikes. Forever more, Saudis have considered the area cursed. The place was never ransacked.

However, the area nearby was eventually lightly resettled. People lived here until 1975 when the government, sensing they could turn this into a tourist attraction, gave them money to relocate. The cleared space allowed for more excavations and some tombs were discovered as recently as nine years ago although mass tourism has yet to take hold.

The construction of the tombs was ingenious. They started at the top of a giant rock. Using a big chisel, they hammered out the tomb shape. They used a smaller chisel to cut out the main designs. They used a little chisel for details, using Greek and Roman designs. What resulted was each tomb had the eagle god Bushalah atop a triangle. Inside the triangle was a snake to protect the tomb. Below it was a string of lotus flowers. The more elaborate the design the wealthier the deceased.

Some of Madain Saleh’s tombs are 50 feet high. Inside were deep, long, rectangular openings with shelves to hold the corpses. At a site called Al Khuraymat, 20 tombs are carved into sheer rock. I see images of lions and wings and spirit guardians with women’s heads. My guidebook says evidence of plasterwork indicates people dined outside family tombs, sort of a Nabataean Day of the Dead. The last tombs featured seven carved side by side about 20 feet apart. We all climb a small sand dune to shoot it from above and just climbing the steep incline of 30 feet made me wonder how these Bedouin nomads live like this every day.

From lookout point

The next day is my last in Saudi Arabia. I take some Spaniards’ advice and drive up to a lookout point. It’s 20 minutes up a windy road along the side of a craggy brown mountain. I pass nary a soul. As it finally levels off, I park in an area with four 50-foot radio towers. A short walk to the mountain’s edge takes me to one of six umbrellas over benches with spectacular views of the valley below. I can see Al-Ula’s small cluster of buildings, the only town I see as the mountains and desert stretch to the horizon.

Standing there huddled against a cold wind, I think about Saudi Arabia’s potential. I’m blessed to be here before the mobs arrive. The country has much work to do. It must build 500,000 more hotel rooms. It must make public transportation available to a site such as Madain Saleh. Human rights violations must be kept in the past and not in today’s headlines.

The current pandemic stopped the country’s progress for a few months. But after nearly two weeks I sense this is a special place. I feel nearly alone in discovering a country with such beauty, cleanliness and culture. The people are so open, I can see how they want to change their country’s image. How far the crown prince is willing to see Saudi Arabia progress in the eyes of the world will be key in attracting visitors. I expect much push back from scoffing friends who read these blogs.

Then again, most of my friends can’t go two days without alcohol, let alone two weeks.

If I met with tourism officials, here is what I would tell them, a list of positives and negatives from a country just beginning to blossom on the world travel radar.

Saudi Arabia positives

- People. Most hospitable I’ve ever met. I got invited into two homes, people helped when they could even if they didn’t speak English and no one denigrated my country or lack of religion.

- Food. Who knew? Saudi Arabia has some of the best restaurants I’ve experienced. Not only was the taste of fresh, lean meats and massive portions of rice great, but the quality was consistent and prices low. I could get tired of the cuisine but for 11 days it’s perfect.

- Smells. These are the sweetest-smelling people I’ve ever met. The women wear heavy perfume and the men pour on the cologne. It’s part of their culture. They have a spice called Ohm which is real expensive. Two ounces are about 30 euros.

- Beaches. Jeddah’s Corniche is beautiful but the White Sands Beach is right out of the Caribbean. And no crowds.

- Roads. All newly paved and there is little traffic outside Riyadh at rush hour. It’s an easy, unintimidating place to rent a car.

Saudi Arabia negatives

- Cab drivers. They don’t have a clue. They’re almost all immigrants who have no idea where anything is, even the national museum and trademark Masmak Fortress in Riyadh. They made me an Uber subscriber.

- No nightlife. I’ve gone 11 days without a drink. I don’t miss it at all. What I do miss are the gathering places that are drinking establishments. I found it hard to meet people here. I got lucky with my networking.

- Internet. It’s spotty at best. Many places don’t have it. It made Maps.me a necessity and it’s not reliable.

- Lack of free speech. When I talked to locals, I had a filter. I can now tell when people lie about their freedom to criticize.

- Coffee. It’s terrible. It’s like watered-down tea. I don’t know what I miss more, a glass of Italian wine or my espresso machine.

Madain Saleh: If you want to go …

Getting there: Choices are limited. In October, for example, there are three direct 1-hour, 45-minute flights from Riyadh to Al-Ula a week, starting at about $210. There are three direct 1-hour, 10-minute flights from Jeddah a week, starting at $226. Bus takes 8 ½ hours and is $65-$85.

How to get around: A rental car is a must. Al Wefaq Rent A Car www.alwefaq.co/en, 966-920-00-2909, open until 11 p.m. For two-plus days I paid 327 riyals (about $87).

Visas: Visas required for 49 countries, including the United States, and can be acquired online at visa.mofa.gov.sa/visaservices/searchvisa. I paid $124.

Time to go: Unlike the rest of Saudi Arabia, Madain Saleh is pleasant all year round. Average highs range from 56 in January to 85 in July.

Where to stay: Rural tents Naseem Alouzaib, Altheeb Area. Has double-occupancy tents for about $110 40 miles from the airport and seven miles from Madain Saleh. Small swimming pool available weather permitting.

Where to eat: Sultana. About a 10-minute drive from Rural tents, it’s the only place that delivers but go for sit-down service. Setting is authentic. Food is massive, delicious and cheap. Ask at hotel for directions.

For more information: Alshitaiwi Travel & Tourism, www.alshitaiwitours.com, 966-11-812-6-789.

July 29, 2020 @ 4:03 am

Excellent! History lives in your writing…and geography too. Thanks to share your experience!

November 16, 2020 @ 1:56 am

Thank you for this very detailed blog post! My family and I would like to visit this place soon and your post is very helpful. Do you think we can rent a sedan or must we drive a 4-wheeler?

July 11, 2022 @ 12:58 pm

Cedan is ok

October 29, 2021 @ 2:13 am

Thank you for sharing. I did this tour/trip with my teenage son via Bus while living in Riyadh….in 1996. The freedoms and liberal travel and visitor visas to Saudi were not in existence then. I often talk about Nabataeans and Madain Saleh to this day. We lived 3 years in Saudi and this one of the most dangerous yet most gratifying bus and educational trips ever. The Highways were not all paved and because of the car bombing in November of 1995 in Riyadh. There was random check points every 30-40 kilometers. 14 expatriates were ordered off bus and searched and interrogated while the bus was also searched. Each stop and search was about an hour. What was suppose to be a 12 hour bus trip each way turned into a 24+ hour bus trip because of threats. We slept in Hunter orange tents for 3 nights with armed Saudi Guards. We loved the tombs and feel so blessed and grateful to see such history. It warms my heart that the Saudis have now opened up tourism to allow others to experience this journey.

July 11, 2022 @ 12:56 pm

There are now hundreds and thousands of branded and unbranded coffee outlets in Riyadh alone. You can have very good coffee of the any brand you are used to.

May 18, 2023 @ 4:18 pm

I was in Jordan and have seen almost everything worth seeing, time permitting. Your description of Saudi Arabia sound attractive. I hope to see The Saudi Nabataeans sites before the mass invasion.

June 13, 2023 @ 4:23 pm

I doubt you have to worry about a mass evasion. Saudi Arabia has such a PR disaster on its hands, I don’t see it becoming touristed out anytime soon.