Matera: World’s third oldest city rocks Basilicata in more ways than one

MATERA, Italy — Living in Rome makes it easier to grasp the history of civilization. After all, it’s nearly a 3,000-year-old city. Almost all of mankind came after it. Much of the world today modeled itself off what Rome created, for better or worse. This city came before the birth of Christ for, um, Christ’s sake.

Now imagine a city that’s 6,000 years older than Rome.

Imagine what is now Italy was nothing more than mountains and marshes and fields. Jesus wouldn’t be born for 7,000 years after this city became established.

I am in the middle of that town now.

Calling Matera’s old town old is like calling Jupiter distant. I’m standing on the lone road, two stone lanes so narrow two cars must squeeze by to pass without sideswiping. Looking up I see a hodgepodge of houses. No, call them dwellings. Or how about shelters? They are piled on top of each other as if some giant built a model city on a mountain with pebbles. Some are built right into the rock, perfect for storing food before electricity.

The yellowish-white stone give Matera a uniformity that takes me back to Sunday school and textbook images of the Holy Land, of chickens clucking and dodging oxen in the dirt-strewn road, of bearded carpenters hammering wood in dusty roadside workshops. I keep thinking I’ll see Jesus trudge through town with a cross on his back which is exactly what Matera’s 60,000 inhabitants saw here in 2003 when Mel Gibson filmed “The Passion of the Christ.”

On the watchability meter, I rank the film down there with “Caddy Shack II.” Yeah, OK, Mel. We all know you say the Jews killed Jesus but do we have to see a man get flogged for two hours? Nevertheless, Gibson knew no town on earth could better replicate a time from 2,000 years ago.

That’s because Matera really hasn’t changed much since then.

Matera is the world’s third oldest city, according to Traveller magazine. Only Aleppo, Syria, and Jericho, Palestine, are older. So unless you like your pizza in a war zone, Matera is the place to explore. Matera was first inhabited in the Paleolithic Era which ended about 10,000 B.C. Back then, Matera’s inhabitants were discovering stone tools and how to hunt and gather. It has been continuously inhabited for the last 9,000 years.

However, the neighborhood where I’m standing and where my Marina and I are staying, wasn’t around less than 40 years ago. It was abandoned, an empty shell of a novelty. It was a forced evacuation, long overdue from a time after World War II when this neighborhood was rife with malaria, where people lived with no running water or toilets, where the infant mortality rate was 40 percent. In 1948, justice minister Palmiro Togliatti called this area, known as the Sassi (Italian for “stones”), a “national shame.”

As I view the chock-a-block stone structures, which come together as neatly as a jigsaw puzzle, I also see dozens of tourists climbing the narrow stairs snaking through the hill and walking the street. Call Matera old. But also call it one of the great comeback stories in Europe. The Roman Empire never rose again.

But Matera did.

“The greatness of this city is they survived all the way from Paleolithic time. So there was a vision of the world.”

Speaking is Vincenzo Altieri, 46, a born-and-raised Materana who owns the La Dolce Vita Bed & Breakfast where Marina and I stayed for three nights last weekend. He has seen Matera grow from an impoverished shell of its former self to a cleaned-up historical site to a Hollywood magnet to one of the growing tourist attractions in Italy.

Today, Matera gets more than 400,000 visitors a year. Forty years ago, you couldn’t get a plumber to come here.

“We take pictures of the city because every day is different,” Altieri says.

Marina, Roman born and raised, had never been to Matera. Like the rest of us, she’d heard stories. We saw photos. I saw “The Passion of the Christ.” I hated the movie but behind the whips, yelps and blood, the scenery was good.

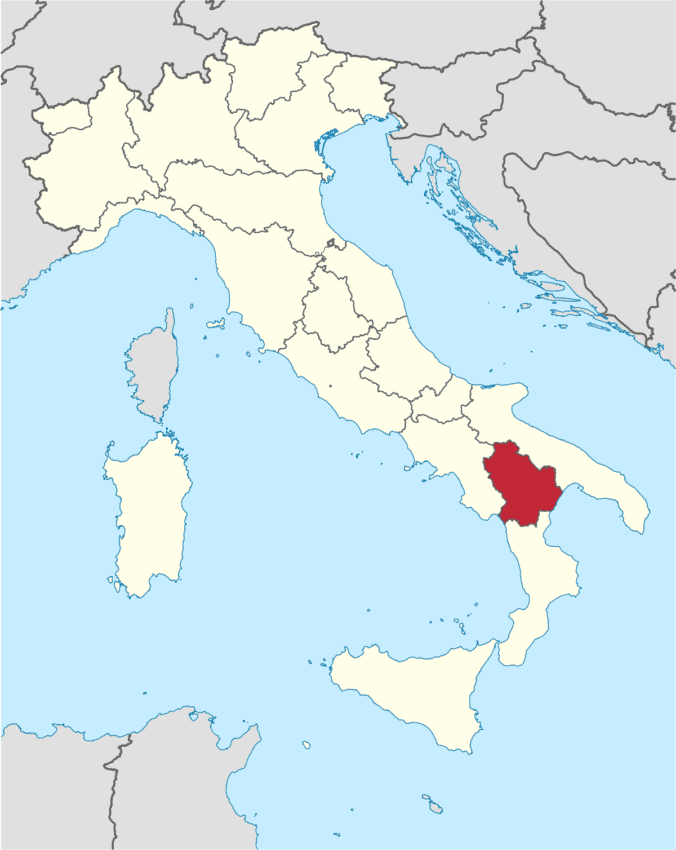

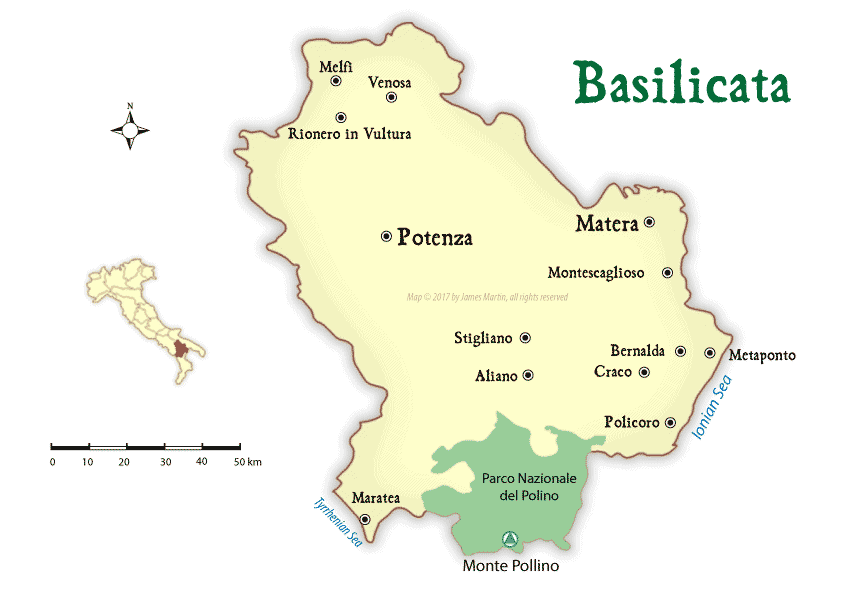

Matera, at 1,315-foot elevation, is not difficult to reach but takes time. Not wanting to risk driving in snow — although the postcards of Matera dusted in white are mesmerizing — we took a bus. The big, modern pullman took seven hours, south through Campania and Puglia before slicing into Basilicata. It’s Italy’s forgotten region, a land of only 570,000 people squeezed between the beautiful beaches of Puglia, the islands of Campania and rural charm of Calabria, the toe of Italy’s boot.

Basilicata is where savvy travelers go to avoid the beaten path. Its once fertile forests are now a mosaic of wheat fields, olive groves and grapevines. The Lucanian Apennine mountains cut through the spine of Basilicata, putting Matera to the east almost in their shadow. Basilicata has a history of toughness. When a discussion of unifying the country swirled in the mid-19th century, loyalists to Basilicata’s ruling Bourbons rose up in violent protest against any political change.

That fighting spirit continued in Matera where 30 years ago they took back the abandoned honeycomb landscape and turned it into their homes again. It is in that neighborhood where Marina and I woke on a crisp, clear 45-degree day, the perfect temperature to roam.

Matera has three sections: The two Sassi neighborhoods are the more impoverished Sasso Caveoso in the south and the more spruced-up Sasso Barisano to the north. To the west is the new town where the Sassi’s great unwashed were moved, most by force, in the 1950s and where Altieri grew up though he wasn’t part of the exodus.

To the east of the Sassi is the Parco della Murgia Materana, featuring a huge gorge with a river snaking through it and hiking paths crisscrossing up the side. It’s as rugged as the people and it’s the panorama we’re gazing at as we climb the first stairs behind Altieri’s B&B.

We walk down a narrow path overlooking the gorge and come across St. Lucia, an 8th century Benedictine convent. It’s one of 170 churches in Matera. That’s one for every 350 people.

“We have more churches than Rome,” Altieri jokes.

It’s 6 euros to enter St. Lucia along with 12th century San Pietro Barisano and 13th century San Giovanni farther north. I always balk at paying to enter a house of worship but here I marvel at the 12th century frescoes, including a rare breast-feeding Madonna. The walls are blackened from age and the two giant white stone pillars are lit from below. It feels more like a haunted house which somehow fits with the theme of Matera.

We walk north along the one main road, Via Madonna delle Virtu, with its spectacular views of the Sassi to our left and the ravine to our right. We cut left up a tiny staircase leading to the Piazza Duomo. Its 12th century cathedral is Matera’s centerpiece, its Christmas ornament where a 52-meter tower can be seen from every vantage point in the Sassi.

From the spacious surrounding piazza, we can see a panorama of the gorge with its tufa walls and tufts of grass in between. Between groups of tourists, including a wedding party where the couple posed with the church in the background, we could hear the river rapids below.

Continuing our journey, we stay on the narrow path above the mob and could smell garlic and hot olive oil emanating from the small houses, some surrounded by potted plants on tile courtyards. Italian food seems to taste better in the countryside, and our stomachs begin to churn despite the filling breakfast of focaccia with tomatoes.

In the tiny wine bar of Vicolo Cielo, we see how Matera reinvented itself into modern Italy. Despite being built inside a cave, Vicolo Cielo is a hip, casual enoteca/sandwich shop where we sit on a big, overstuffed couch. Across from us, under the white, naturally arched ceiling, sits a shoeshine chair, for no apparent reason.

As Led Zeppelin’s “Ramble On” plays on the loudspeaker, the young waitress brings me a panino (not “panini,” Americans) of crudo ham, gorgonzola cream, tomatoes and lettuce between thick slices of Basilicata’s famous soft bread.

A benefit to modernizing a hovel into a tourist center is Matera’s food options are tremendous. Besides bread, Basilicata is known for its terrific cheeses, including a scrumptious Caprino a Vinacce displayed beautifully at Caveoso, another restaurant built into a cave. At Morgan, one of the first restaurants established in the Sassi in 1997, I had two of the best sausages in my life, taken from Cirigliano, 15 kilometers from Matera. I also took a recommendation for Soul Kitchen, one of Matera’s most elegant restaurants where my unique potato ravioli was filled with bufala mozzarella and covered in pesto and tomato sauce. Washed down with the local Primitivo house wine served all over town, Matera hits all the gastro points.

You need fuel. The town is bigger than you think and there are so many strange things to see. It’s like a living funhouse with a religious bent. One of Matera’s most bizarre sites is San Pietro Barisano. The church was plundered in the 1960s and ‘70s, leaving the altar empty and some of the surrounding statues without heads. But below the floor is a maze of narrow passageways with 4-foot-high niches in the walls. This is where they placed corpses during draining. The close quarters are too much for the slightly claustrophobic Marina but I inch my way along the walls imagining dead bodies lined up like bowling pins. As I touch a wall, some of the tufa crumbles in my hand.

As we walk from church to church, I can’t help noting that it’s not a coincidence so many were built in a town that looks like old Bethlehem. You feel as if you’re walking through one giant presepe, the native scenes from the Holy Land you see all over Italy as Christmas nears.

This is why the most beaten path to Matera has been made by the movie industry. Twenty-five movies have been made here, starting with Pier Paolo Pasolini’s 1964 film, “The Gospel According to St. Matthew.” In 1979 came the hit “Christ Stopped at Eboli.” Later, in 2006 they filmed the Jerusalem scenes in the remake of “The Omen,” my favorite movie of all time. Last year Morgan Freeman pounded the stones here in the filming of “Ben-Hur.”

But the film that launched the flood of tourists was “The Passion of the Christ.” For three months the crew took over the town. In fact, right next to our B&B, Jesus, played by Jim Caviezel, fell during one of his many savage beatings.

“You’re living here so you’re living on the set even if you don’t want to,” Altieri says. “You see Romans. You see camels. You see horses everywhere. You get used to it.”

Ironically, a generation earlier, another movie had a bigger influence on the Altieri family. In the 1950s, most of Matera’s population lived in the Sassi. Today the city has a sample cave in which we saw a room about 50 square meters where 12 people lived. That didn’t include a horse and chickens in one of the rooms. A bed was shoved in the corner under a small loft. An iron pot sat under the bed. That was the toilet. The room had no drainage. No electricity.

This was 1965. It was during this time the government, tired of the black stain Matera put on the Italian landscape, started moving people into the new town.

During this time, the older brother of Altieri’s grandfather went to his first movie. It was “King Kong.” Suddenly, the Meterana saw themselves as the government did: as backward as an oxcart.

“Just by the images he realized, ‘OK, there are skyscrapers, women without moustaches, fancy dresses, cars, boats, airplanes, animals I’ve never seen,’” Altieri says. “There’s a different reality out there.”

Altieri grew up in a typical Italian family with 11 other members. If all roads lead to Rome, few led to Basilicata. They were nearly isolated. The government all but forgot them. Then in 1986, the government allowed families forced out of the Sassi to return and fix them up with their own money.

In 1999, Altieri took a two-story building just off the main road. A software engineer at the time, he started to rebuild. He shows me photos of our room at that time and it was a barren pit. It looked like a flood had hit it. But he went to work and later turned it into a thriving B&B with a patio overlooking the sassi.

“This place (Matera) was meant to share,” he says. “There was a wisdom of looking at the world and saying, ‘OK, we can do better even though we have no resources. We will succeed.’”

It’s our last night, and we go to Sunday mass. I’m not religious but living in Italy, mass is a cultural event. Marina goes regularly, and I learn more about her life and my adopted country’s traditions by sitting in church for 45 minutes. It’s was held in San Giovanni, made of gray and white stone, beautiful in its simplicity.

The priest, a short, young man in a brilliant purple robe, talks about how the real sense of life is having time for brothers and sisters and family. He says modern man doesn’t have faith, that he must keep the faith.

Matera has kept the faith for 9,000 years. That’s a passion Christ could appreciate.

December 14, 2017 @ 10:44 pm

What a beautiful city!

December 15, 2017 @ 1:06 am

In a country of beautiful cities, Matera stands out. It’s even prettier from the inside. Thanks for the comment.

December 14, 2017 @ 11:07 pm

Matera is amazing, almost mystical. I also ate at Trattoria del Caveoso. I would recommend anyone going to Matera read Carlo Levi’s ‘Christ stopped at Eboli’. I only went as a day trip from Puglia, but I’d like to go back and stay for 3 days. Ciao, Cristina

December 15, 2017 @ 1:05 am

Thanks, Cristina. Yes, spend the night. That way all the day trippers go back to their hotels and you have the town to yourself and the locals. Although last weekend I think every Materana was out. I have to rent “The Passion of the Christ” again. I’ll mute it so I don’t have to hear Jesus wail for two hours. I just want to see the background.