Montenegro: My long-awaited return reveals one of world’s hottest new travel destinations

(This is the first of a three-part series on Montenegro.)

PODGORICA, Montenegro – Forty-five years is a long time between visits anywhere. In Eastern Europe years, that seems like 100. Capitals put up lights and get a fresh coat of paint. Hotels emerge in unspoiled countrysides. The streets get swept.

Blink and you’re looking at a new country, bright eyed and roaring into a world of democracy, western fashion and mascara.

I thought of this two weeks ago when I landed in Montenegro, the last Yugoslavian republic to gain independence in 2006, 14 years after its five republic cousins did. It also had no visible scars. It was the only one not affected by the Balkan War of the 1990s. In 1978 I traveled through Montenegro during a year-long trip around the world. I took a bus from Dubrovnik, Croatia, to Skopje, Macedonia, with plans to crash at the halfway point in Titograd, Montenegro’s capital.

I remembered entering the city and seeing nothing but dirty, gray concrete apartment towers, as depressing as 10-story gravestones and just as ominous. Titograd, a rigid salute to sorry communist architecture, appeared dead.

I stayed on the bus to Skopje.

Podgorica

This time I arrived to a new city, a new country and a new outlook with a new government. Montenegro has become one of the fastest-growing destinations in the world. It’s a country the size of Puerto Rico but, with only 625,000 people, just 20 percent of the population. Yet Montenegro has mountains lining the horizon, beaches with crystal-clear water, rivers I drank out of and national parks crisscrossed with hiking trails where I rarely saw another soul.

In 2007, a year after Montenegro voted for independence and broke away from governing Serbia, it attracted 1 million visitors. In 2019 it had 2.5 million. Tourism makes up 20 percent of the economy.

“We’re growing up very fast,” said one restaurant owner who wanted to remain anonymous. “Before we didn’t have much marketing. But if people come to Montenegro one time, they come every year.”

Yes, he requested anonymity. He feared government reprisal for other things he said. So did every other Montenegrin I talked to during a 10-day journey that went from the city to the mountains to the beach and to the bay. It’s 17 years since independence and lingering paranoia remains from a government that just vacated office after nearly two decades of thinly veiled corruption.

Some aspects of communism never change.

Take Titograd. To cynical Montenegrins, the only thing that changed is the city’s name. In 1992, it became Podgorica (pod-go-REETZ-ah), its name from 1326-1946 before being named for Josip Broz Tito, Yugoslavia’s vastly underrated president.

Today, Podgorica is the country’s dartboard. It has a worse national rep than 1960s Cleveland.

“I hate it,” said one young woman working in an art store. “You know those big, ugly apartment buildings from the ‘60s? They’re still there. It’s only good for college.”

Yes, those buildings are still there. After 45 years, I recognized them. My taxi went right past them on my way in from the airport. Well-traveled colleagues on Whatsapp told me not to stay in Podgorica. Most visitors don’t even go. They fly into Tivat, a pretty marina town and gateway to the Bay of Kotor and the Adriatic beaches, Montenegro’s signature destinations.

I liked Podgorica. It’s not just because capitals have a better pulse on a country’s politics or my Hotel Alexandar Lux had a spa right out of a Turkish romance novel. It’s because it’s trying.

The hotel Lux is in the middle of Nova Varos, the pulse of the country’s nightlife. On a perfect 75-degree night, I prowled the crisscrossing streets of Bokeska and Njegoseva lined with bars with names like Culture Club Tarantino and the Loft and Prostar. On a Monday night, every bar’s outdoor seating was packed. Adults of all ages drank designer cocktails and Montenegro’s national Niksicko beer with the heavy beats of house music colliding like midair airline crashes.

Down the street, my first Montenegrin meal gave me an introduction into an obvious conclusion at the end of the trip. I don’t know if vegetarianism is illegal in Montenegro, but I believe if you order some baby greens they’ll ship you to Albania.

Montenegro is one of the most meat-heavy countries I’ve ever visited. Pod Volat is a restaurant in a 100-year-old converted house next to a huge clock tower. Now a monument, it was used to signal Muslim prayer times when the Ottomans ran this region for 400 years until 1878. In a courtyard under two trees I had podgoricki popeci, three huge meat rolls stuffed with ham and cheese and covered in a heavy cream sauce.

I waddled out and wondered why Montenegro has so few fat people. Then I began to travel. Over 10 days I learned there is so much to do in Montenegro, you can’t sit still for long.

Sveti Stefan

I spent the next five days white-water rafting and hiking in the shadows of craggy, forest-covered Dinaric Alps which cover about two-thirds of the country. I’ll describe the rafting and hiking, including a two-hour climb to the father of the country’s tomb, in my next two blogs.

What I’ll say now is I made it to the back of beyond in the Balkans. Lonely, narrow roads zigzagging up mountains with only occasional hand-painted road signs. Cow crossings. Shepherds in tattered, traditional clothing wandering with their staff in hand, looking as if they lost their flock. Spectacular views of the forests and the bays and the sea.

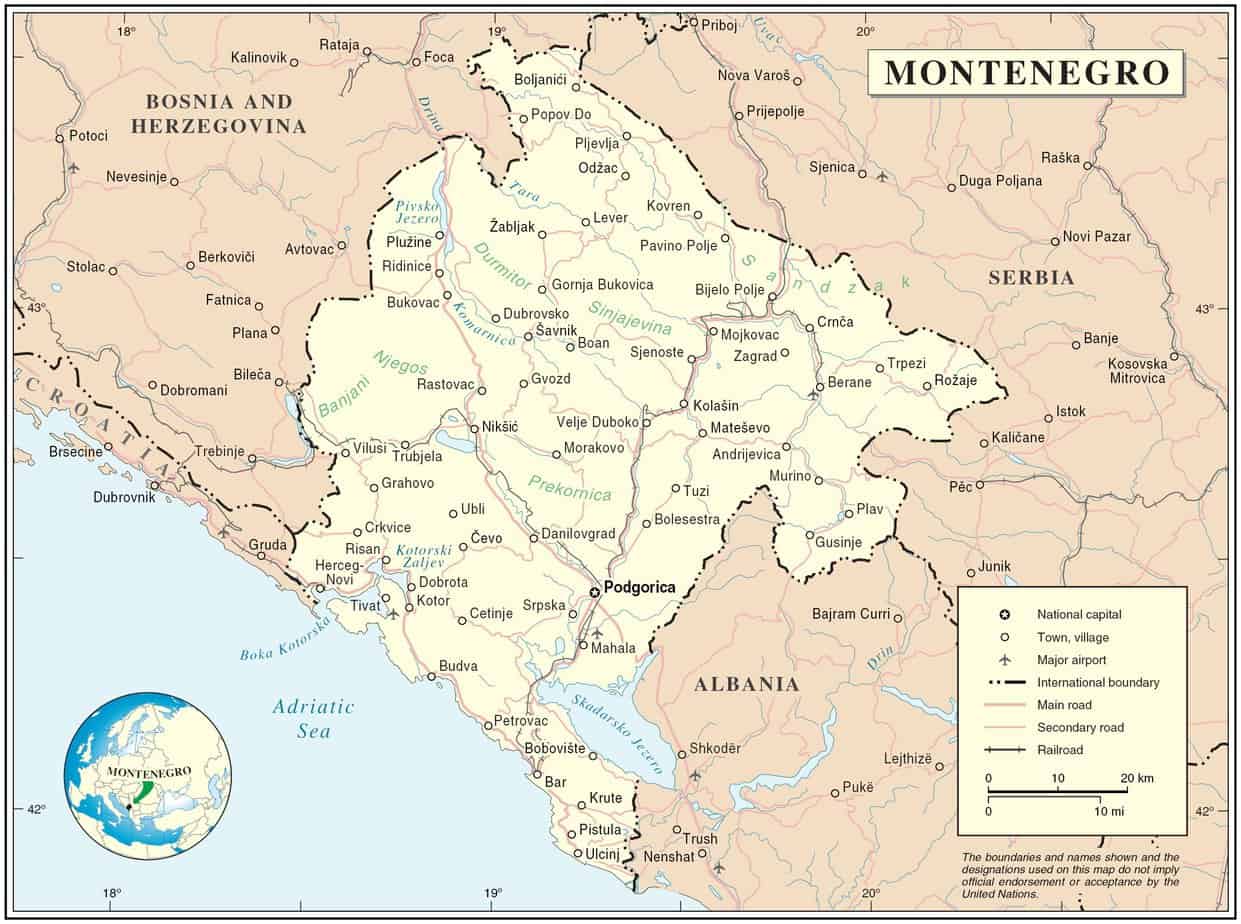

The majority of people, however, come to Montenegro for the waters. Look at a map and Montenegro’s coastline is only 180 miles (290 kilometers). However, it is lined with some of the purest water in Europe with beach towns that have yet to turn into aquatic theme parks.

Also, pouring into the adjacent Adriatic Sea is the Bay of Kotor, three bodies of water connected by isthmuses and dotted with cute villages and ports screaming for calamari and a glass of white wine.

I took one of the many cheap and reliable buses to the village of Sveti Stefan. Located just 35 miles (60 kilometers) from Podgorica, Sveti Stefan has all of 413 residents. My bus stopped at the town’s high point, atop a cliff where my room at the Hotel Adrovic looked down to the island that made the town famous. On a big rock no larger than a couple city blocks is a hodgepodge of 15th century stone villas.

It has turned it into an outrageously expensive Aman resort where tennis star Novak Djokovic married in 2014 but it makes for great photo ops at sunset or on the beach. Despite the relatively short stretch of shoreline, Montenegro doesn’t get the cheek-to-cheek mobs as beaches other Adriatic countries get in Croatia, Greece or Italy. Sveti Stefan doesn’t even have many hotels.

However, to go to the beach from my hotel, you must really want to go to a beach. It is 318 steps down. (I know. I counted. Twice.) What’s worse, they are 318 steps up.

Then I gladly paid the €15 for a lounge chair. No one can comfortably lay on the beach made up entirely of large, jagged rocks unless you’re a sand crab or an Indian fakir. People precariously venturing from their chair to the water all looked like they were walking across hot coals with broken ankles. It was the most uncomfortable beach of my life.

But the water, cool, clean, calm and still warm water from the steaming summer, made the pain worth it.

Kotor

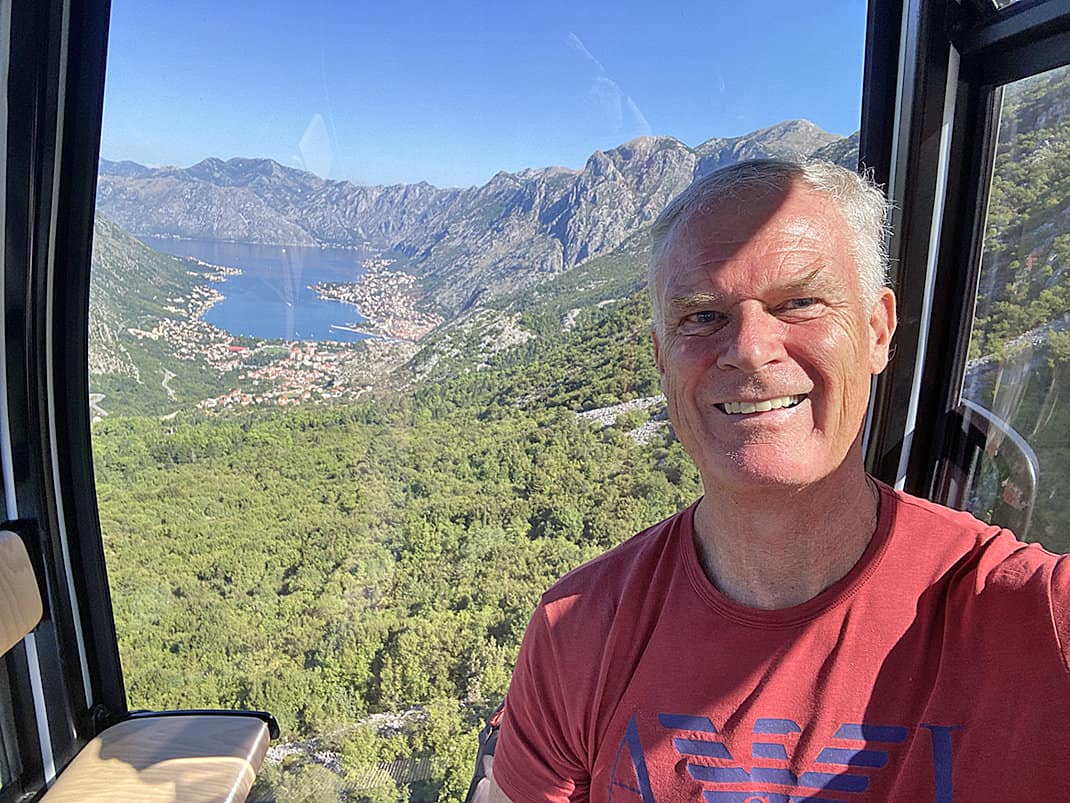

To reach Montenegro’s most popular town from Lovcen National Park, where I spent three days hiking, I had two options: One, have a taxi drive me down a series of hair-raising, hairpin turns with no guardrails 5,000 feet (1,500 meters) to the sea; two, take a cable car that opened just one month ago for 10 minutes with some of the best views in Europe.

Let’s see. A €40 taxi that could result in mass death or a comfy €23 cable car ride that I’ll remember the rest of my life? My hotel shuttle took me through a dusty construction site to the cable car which sits like a space station high atop a cliff. They were putting the finishing touches on a roller coaster that would dip down the cliff for anyone wanting more than a good view.

Next to the cable car is Forza Kuk, an elegant restaurant with patio seating offering views that reminded me of Yugoslavia’s raw beauty from 45 years ago. As I sat drinking my cappuccino, below was the triangular Bay of Kotor with the town of Kotor wrapped around the lower-right corner and various villages dotting the shore. Beyond the hilly forest was the Adriatic Sea, royal blue in the 80-degree sun.

As the cable car descended, I passed the zigzag road creeping up the mountain. Cars nearly came to a stop to turn. God forbid another approached. The road barely had room for a scooter carrying a skinny passenger.

Unfortunately, the view far surpassed the destination. For all of Kotor’s hype – it regularly appears on Europe’s Prettiest City lists and is a UNESCO World Heritage Site – it disappointed me. Considering the country is getting its tourism legs under it, I’ll call it Montenegro’s first tourist trap.

This coastline was part of the Venetian Empire from 1420-1707 (Montenegro is Italian for “Black Mountain”) and Kotor plays up the Italian angle. There are bars called Niente (Nothing) and Bandiera (Flag). A boutique hotel is called Palazzo Drusko. Italian restaurants and pizzerias are numerous.

Adding to the Italian feel, healthy, well-fed stray cats are everywhere. They’ve been around since the seafaring men brought them to protect the town from rats and snakes. Tapping into their feline trademark, Kotor shops make you feel you can’t leave without a kitty keychain.

Kotor sits inside huge walls built between the 9th and 14th centuries. To enter, I walked through the Sea Gate built by the Venetians and features a communist star representing Kotor’s liberation from the Nazis and a quote from Tito saying, “Do not take ours. We do not take yours.”

Inside the walls, Kotor stretches out in a maze of narrow alleys connecting various piazzas. They’re lined with souvenir shops and outdoor cafes. It’s like a couple dozen cities in Italy where I live. I kept thinking, What’s the big deal?

I took a no-frills room at Hotel Rendez Vous on quiet Piazza Mlijeka. Trees provided shade on a horridly humid afternoon. The restaurant served some mean Montenegrin fare, including a Karadjordje, a pork cutlet filled with ham and cheese, breaded and topped with a type of tartar sauce.

It’s named for Dorde Petrovic, the Serbian leader nicknamed Karadorde (Black George in Serbian) for his fight against the ruling Ottoman Empire from 1804-1813. Only in the former Yugoslavia can eating make you think of its star-crossed history.

Montenegro politics today

Despite being spared the violence of the Balkan Wars, an independent Montenegro has not been spared political turbulence.

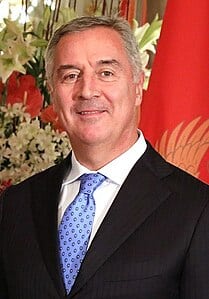

Milo Djukanovic, a communist holdover who ran Montenegro for three decades, was Europe’s longest-serving leader until he lost his election in April. In 2010 he was also ranked as the 20th wealthiest world leader.

“He took everything Tito left,” one waiter told me.

Djukanovic ruled under a heavy cloud of suspicion. Rumors of corruption and connections to organized crime gangs followed him wherever he went. He denied them all but when western law enforcement agencies uncovered Montenegrin police communicating with local crime gangs on cocaine shipments, Djkavonic’s armor began to crack.

Jakov Milatovic, a 36-year-old Oxford-educated former economist, defeated Djukanovic in April and is trying to steer Montenegro clear of suspicion. The country joined NATO in 2017 and is on the waiting list for the European Union. Today almost 20 percent of Montenegro remains in poverty. Tourism is up but many locals I met weren’t optimistic about the overall future.

“Some things are better but not in the roots,” one said. “It’s like building a house without a foundation … I have friends in America. When you live in America you know how Friday looks, how Monday looks and next year. Here you can not see. So how am I optimistic?”

Meanwhile, Montenegrins and Serbians live together in a country that was once part of Serbia and is still seeking an identity.

“When you have two brothers from the same mother and father and one (is called) Serbian and the other (is called) Montenegrin, I tell you everything by that,” one man in Podgorica told me. “People are giving such weight to that question. Name. Nationality. Religion. It’s like a Balkan illness. It’s totally true. It exists. It doesn’t have to be 100 years in the past to get the historical point of view.

“Even two or three years from the last election.”

I’d sure like to see it in another 45 years.

Next Tuesday: White-water rafting in Montenegro.

If you’re thinking of going …

How to get there: Many European airlines fly into Podgorica. Tivat Airport, five miles from Kotor, has flights from Belgrade and Moscow year round but numerous cities fly to Tivat in the tourist season.

Where to stay: Hotel Alexandar Lux, 12 Hercegovacka, Podgorica, 382-20-664-510, https://alexandarlux.com/, info@alexandarlux.com. I paid €70 a night including breakfast. Excellent hotel in the middle of city’s nightlife with a killer spa featuring a Jacuzzi, sauna, Turkish bath, cold pool and indoor swimming pool.

Hotel Advovic, Jadranski pul bb, Sveti Stefan, 382-33-468-507, https://www.hoteladrovic.com/, hoteladrovic@t-com.me. I paid €190 for three nights. Located right next to bus stop, has great views of the sea and elegant but expensive dining room.

Where to eat: Pod Volat, 1 Trg Vojvade Becira Osmanagica, Podgorica, 382-69-618-633, restoran.volat@gmail.com, 7 a.m.-midnight. Best place in capital for inexpensive, traditional Montenegrin dishes. Mains starting at €5.

Rendez Vous, Pjaca Od Miljeka, Kotor, 382-69-043-377, 8 a.m.-1 a.m. Connected to inexpensive hotel on quiet, shady piazza, a good place to eat traditional fare and watch soccer on the big screen with the friendly wait staff.

How to get around. Most people rent cars from an airport but some paid as much as €300 a week. I relied mainly on the cheap, reliable national bus system which runs frequently to all towns. Over seven trips using four buses, two taxis and a shuttle, I spent only €63.

When to go: As I always advise, avoid all of Europe in July and August. September temperatures ranged from low 50s in the mountains to high 80s on the bay.

For more information: National Tourism Organization, 382-80-001-300, www.montenegro.travel.

September 26, 2023 @ 4:17 pm

Great post, John. We loved Kotor.

September 26, 2023 @ 5:33 pm

I know you did. Keep in mind, I came from Italy where there are so many walled cities with not near the number of tourists.