Naples Underground: an eerie walk through 2,500 years of dark history

NAPLES, Italy — Sunday will mark one year since I have been outside Italy. It’ll be the longest I’ve gone without leaving a country in more than 40 years. Not that my travel bug is gnawing at my insides but I’m looking at my globe as if it’s a planet far, far away. Or, put in other words, my recent trip to Naples felt like going to the far side of that same planet.

Naples is a 70-minute train ride from my home in Rome. During this global pandemic in Italy, any trip out of town is more fantasy than reality. We’ve been in and out of lockdown for nearly a year. When the government collapsed last month, the regional borders opened — but only for “essential reasons.”

This time I had one: work. With Italy lowering its Covid-19 restrictions, much to the horror of cautious scientists and health officials, museums and public attractions finally reopened. That includes one of the most fascinating sites in Italy and one of the attractions of the underrated city of Naples.

Napoli Sotterranea, or Naples Underground, is a vast maze of narrow tunnels, shallow pools and vast rooms 35 meters under the street and dates back to the 5th century B.C. Started by the Greeks, modified by the Romans and used by the terrified Neapolitans as a bomb shelter during World War II, Napoli Sotterranea came across my radar after it reopened Jan. 18.

To get there, I had to abide by Italy’s strict travel regimen. I filled out Italy’s auto certification form that states my reason for leaving Rome’s Lazio region including my ID number, address, place of birth, date and destination. At Termini train station I presented it to the train clerk who examined it with the intensity of an East German border guard. He kept the form and Marina and I hopped on a train that was practically empty. I counted all of six other people in our car.

The plus side is the journey in a near empty train is glorious. We took Italo, Italy’s modern, ultra-fast trains that operate like U.S. airlines. If you book far enough in advance, you get much cheaper rates than the old, beat-up trains with Trenitalia. Marina and I sat opposite each other with a table in between. We read, looked out as the rolling hills of the Campania countryside came into view and then saw Mount Vesuvius to our left as we pulled into Napoli Centrale station.

Naples Underground arrival

Arriving early enough for lunch, we took a taxi to Naples’ San Lorenzo neighborhood. San Lorenzo is the most densely crowded neighborhood in Naples with 50,000 people crammed in a labyrinth of streets. If a film crew wanted a true taste of Naples, they’d come to San Lorenzo. Narrow roads barely wide enough for a single car lay under lines of laundry. Fruit and vegetable stands anchor street corners. Vespas race up and down the streets like they’re escaping another Vesuvius eruption.

I love Naples. It’s loud, lusty, passionate. The Napoli Sotterranea people recommended we eat at Di Matteo, a “famosa pizzeria” just down the street. It has been in this same spot since 1936 and looks it. An old wood-plank sign with painted words hangs over the window where you can see men in long white aprons making pizzas. We saw photos of President Clinton in a sharp black suit with his mouth full standing with the beaming kitchen crew.

We went up a steep, narrow staircase to a small dining room where I had the best arancini in my life. Arancini are fried rice balls famous in Campania. They’re filled with different ingredients such as mozzarella, sausage, mushrooms. This one had mozzarella and peas and melted in my mouth. Not an ounce of grease could be detected.

Then came a bufala mozzarella and tomato pizza Neapolitan style. The thick, doughy crust is the trademark of the city that invented mankind’s favorite food. The tomatoes were fresh. The mozzarella was tangy. It was piping hot. No better meal to prepare for descending into the earth’s depths.

The entrance

The entrance to Napoli Sotterranea is the end of a short alley next to a church and looks like the entrance to a cave. Greeting us were Vincenzo Albertini, the founder of the site, and Nadia, our English-speaking guide. On a chilly, windy day, we were the only guests. We had our own private English-language tour.

We followed Nadia down a dark stairwell. It takes 142 steps to reach 35 meters under the earth.

“It’s like going to the subway in Naples,” Nadia said.

The stairs emptied to a large room lit with electric lights on the stone walls. The ceiling was 50 feet above us. I could hear the faint sound of trickling water somewhere. This should be a popular site during Naples’ steaming summers. The Sotterranea is 60 degrees all year round.

The history

This site isn’t just a visual marvel. It’s a history lesson that covers the breadth of Italy and not just Naples. The Greeks settled this area in 680 B.C. and called it Neopolis or New City which later morphed into Napoli under Roman rule.

First, the Greeks dug wells this deep underground to bring water up for their new city. To build the buildings, they took the surrounding stones up as well. It’s tufo stone, volcanic rock that is all over this area between Vesuvius 17 miles to the east and Campi Fleigrei, 10 miles to the west.

I asked how they dug this far underground about 2,500 years before the first concrete drill was invented. She pointed to a couple of crude hand trowels that looked more suited for someone’s garden.

“It took them centuries,” she said.

When the Romans ran off the Greeks in 326 B.C., they transformed the caves into a major water system in the 1st century B.C. With water coming from nearby Monte Sereno, the Romans connected all the caves with narrow tunnels. At its height, this underground system covered 125 miles. Thus, the ancient Roman aqueduct was built.

“The Romans were the best for aqueducts in all of Europe,” Nadia said. “In Germany in Cologne there is an aqueduct 30 meters over the street. Here it’s 30 meters under.”

It remained an aqueduct for 2,000 years but a cholera epidemic in 1884 closed the aqueduct and 14,000 cisterns of water. The city instead built an aqueduct above ground and what did the Neapolitans do with the wells?

Garbage.

Naples had a shortage of garbage cans (No! Make that DOES have a shortage of garbage cans) and the population used the 14,000 wells as public trash bins. By 1940, Naples had 1.4 million people (compared to 3 million today). Now imagine the stench of this place after 1.4 million people threw everything from pizza crusts to spoiled tomatoes to dirty diapers 35 meters underground.

Now try to imagine the poor sonofabitch who had to clean out these wells in 1942 during World War II when Naples decided to turn the Sotterranea into a bomb shelter. Actually, Nadia explained, the amount of garbage forced the city to simply build atop of it.

Next, they built stairs down from 20 entrances to the underground. The third modification was to close all the wells. Allied forces bombed German-occupied Naples 200 times. Having one fall through the well into a room full of terrified citizens would somewhat defeat the purpose of a bomb shelter.

In one area cut into the rock, we saw different sizes of rocks used to build Naples. Some are hovering in the air on a crude rope pulley hung from the ceiling.

Hanging elsewhere in the room was a large painting of what looked like a woman. Before the pandemic, the city used the Sotterranea for art exhibitions, theater performances and classic music concerts. Artists have come in and took crude metal and made them into children’s toys to show how some of the people lived down here.

We walked down a dark hallway to another large room. Nadia pointed up to a hole in the ceiling.

“Here you see the only well open in Naples,” she said. “It’s open because we are under a garden of a church now. The people believed nobody would bombard a church. But it’s not true. They did.”

An estimated 20,000-25,000 people died in Naples during World War II. This underground saved thousands. However, it also created some lives. Nadia said many German soldiers also used the shelter when they deserted the army.

“They had so many love stories with Neapolitan women,” she said.

We moved to another huge room and on one end on opposite sides are about two dozen crude, broken-down stone dividers. They were toilets, discovered by archaeologists only eight years ago. In other rooms we saw leftover weapons, gas masks, Nazi uniforms and bombs hanging ominously three feet off the ground by a thin rope. Only the tank is not from World War II.

“They could hear the bombs from down here,” Nadia said.

We then entered another room where five brilliant light bulbs hung over a raised stone platform. Under the lights was the only other sign of life we saw.

Plants.

Long, leafy, healthy plants sprouted from a minimal amount of dirt on the platform. They’ve found they can grow strawberries and tomatoes 35 meters underground. It’s all an experiment.

“We’d like to see if, on Mars for example or other planets, you could grow something like this for food in the future,” she said. “If it’s possible to live underground.”

The tunnels

The next part of the tour comes with a warning, one that is loud and clear to all the tourists who gather outside above ground. Huge pools of water still exist down here. However, to reach them one must navigate very narrow and dark tunnels. They were designed narrow to increase the water pressure. However, they are so dark you must carry candles that sit illuminating like big fireflies just outside.

Nadia says the first one is about 40 meters long. Marina, slightly claustrophobic, wanted nothing to do with it. I am a little claustrophobic but primarily in tight enclosures in underwater caves. I’ve done them, and I hate them.

I picked up a candle.

I followed Nadia and had to bend over to keep my head from scraping the ceiling about 6 feet high. Marina’s daypack I carried scraped against the sides of the tunnel. The candle only illuminated the walls. Nadia, scooting along as if walking to her living room, was merely an outline. I counted the seconds. It’s 1 minute and 15 seconds, and I made it through without hyperventilating or turning around.

Claustrophobes are warned to stay away.

“The people who are very claustrophobic never come down,” Nadia said. “They don’t even come down the first steps.”

However, it is well worth the trip. In front of me under the 35-meter ceiling was a big pool that wouldn’t be out of place behind a hotel. The water is two meters deep, well below the five meters of the wells 2,000 years ago. The water looked clear and clean. I asked how it circulates.

“It goes from one system to another,” Nadia said. “The big system like this worked under the square. The population came to take the water. Rich people had their own system under their house.”

We entered another narrow tunnel, another 75 seconds of dark, cramped maneuvering. Another huge pool. In an opening high up the wall I saw other plants growing under the light.

We returned the way we came and picked up Marina who thanked me for not dragging her and her camera through the tunnels after I told her the experience. She was more than glad to climb the 142 steps back to the surface.

One of the best parts came next. Nadia took us out the entrance and to the church on our left. San Paolo Maggiore was built in the 13th century but holding up the facade are two Greek Corinthian columns. They looked terribly out of place but are a terrific ode to the Greek presence here 2,500 years ago.

This is where a Greek temple once stood.

The theater

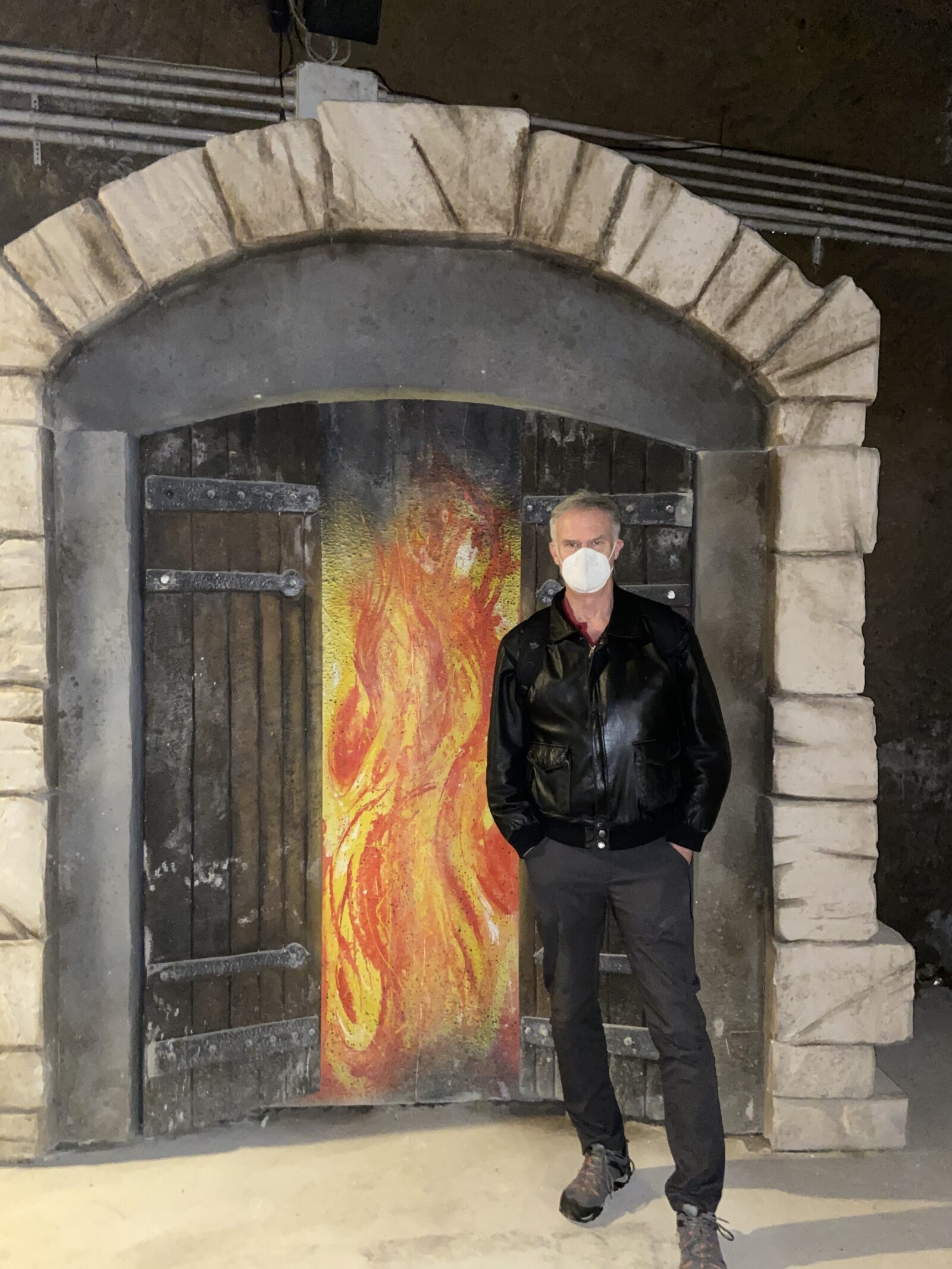

We walked about 50 meters up Via Cinque Santi where Nadia opened a crude lock on an ancient door. We were about to enter the remains of an ancient Roman theater. Today more than 200 apartments are built atop of it but Albertini, the Sotterranea’s founder, discovered it under the modern construction.

He bought one of the tiny apartments, called a basso (“short” in English), and started chipping away at one of the walls. He found Roman brick. He cut away more and found the backstage of the theater.

Nadia took us through and brick archways and led us through the hallways where the actors hung out between scenes. One hallway took them to the other side of the stage where they could go without the spectators seeing them. Some famous men performed here.

Ever hear of Emperor Nero?

“Before he burned Rome, he did theater,” Nadia said. “He believed he was a great actor. He came to Naples because it was the last Greek city in this period.”

Afterward, I took great gulps of the cold crisp air and sat down with Albertini. The 60-year-old geologist grew up right behind the church and as a curious 14-year-old frequently explored the nooks and openings of this underground site.

“There were so many entrances here,” he said. “I’ve had this passion since I was little.”

His parents, both Neapolitans, also harangued him with stories of their own escapes to the underground when the bombs came. The Sotterranea not only was a window to 2,500 years of Naples history but his family’s history as well.

It led him to an education in geology and he opened the underground to the public in 1989. It closed March 8 after the pandemic hit, reopened June 5 and then closed again Nov. 2 before reopening, again, Jan. 18.

I asked him why this site is so important to Naples.

“Because we’ve seen there was a Roman market, a temple,” he said. “It was the most important part of the city at the time. It could be important for the tourists to see everything again. I believe this could be a good entrance to start the tours of Naples.”

One thing about Neapolitans is they are fiercely proud of their city. When we visit, Marina has no idea what the locals are saying in their Neapolitan dialect. It’s like Naples is different from the rest of Italy. It’s where Greeks and Spanish ruled and the chaos that gripped the city for two millenium is still evident in the streets and culture.

I love the chaos. The Neapolitans are proud of it.

“Naples has everything from the old history to today and it’s one of the most important cities for the history,” Albertini said. “Before Italy, before 1861, Naples was the most important city in Europe.”

We walked through one of the city’s poorest neighborhoods, rife with immigrants and a couple of old drunks, one of whom forgot to zip his fly after peeing somewhere. But as we took the comfy train back to Rome, we only thought of the underworld we just visited.

However, interested visitors must wait again. On Sunday, Campania’s Covid level of restrictions went to orange, meaning all museums are closed until further notice. It’s life in pandemic Italy where not only the underground is in the dark.

If you visit …

Where: Piazza San Gaetano 68, Naples.

Tickets: 10 euros adults, 8 euros students 6 euros under-10.

Hours: Tours in English at 10 a.m., noon, 2 p.m., 4 p.m., 6 p.m. Tours in Italian at 10 a.m., 11 a.m, noon, 1 p.m., 2 p.m, 3 p.m., 4 p.m., 5 p.m., 6 p.m. (Note: Currently closed due to Covid levels but may open in near future. Hours are modified during pandemic.)

How to get there: Several trains leave daily from Rome’s Termini station to Napoli Centrale. Times range from 70 minutes to three hours. Round trip on Italo, if purchased in advance, is about 30 euros. Taxi to site is 10 euros.

Contact: 39-081-019-0933, info@napolisotterranea.org.

February 23, 2021 @ 6:20 am

Under the amazing Basilica of Santa Maria de Sanita are the Catacombs of San Gaudioso. We toured with the young people of the neighborhood who participate in a collective to build economic and political power to resist the gangs. Another amazing Neapolitan story.

February 24, 2021 @ 3:49 am

Thanks for the tip, Irene. I’ll have to check those out next time.

February 23, 2021 @ 12:38 pm

A great additional follow up to “Searching for Italy” by Stanley Tucci which we are able to see on CNN Sunday nights at 9 pm. His first one was Napoli and he eats his way through the country.

February 24, 2021 @ 3:48 am

What is with Stanley Tucci? Everyone is watching this guy? Thanks for reading me, at least.

February 23, 2021 @ 8:25 pm

I have been watching Stanley Tucci “Searching for Italy”. Too bad he did not meet up with you.

This post was very interesting and enlightening. I have been to Naples but did not know about the underground so it was great history lesson. Thank you!

February 24, 2021 @ 3:48 am

Thanks for the comment, Filomena. I’m sure getting tired of hearing about Stanley Tucci.

February 23, 2021 @ 10:43 pm

Great stuff as always John!! Thank you for this! It’s on my list now.

February 24, 2021 @ 3:47 am

Thanks, Mike. Go in the summer when it’s a nice respite from the heat.

February 24, 2021 @ 3:46 pm

Fascinating history of Naples. I am definitely visiting on my next trip…whenever we can leave Australia!

February 24, 2021 @ 6:54 pm

This is SO cool! I will admit Naples has always intimidated me a bit, yet the way you wrote about it is endearing. You did a terrific job of explaining why it’s unique and not to be compared to essentially anywhere else. I will look at it from a fresh perspective next time I have the opportunity to visit. I must admit, I’m with Marina about the narrow passages, but the destination sounds like something worth suffering a little. I didn’t even know this existed before your article. Thanks for opening my eyes to the many wonders of Italy – can’t wait to come back! Ciao!

February 27, 2021 @ 7:38 pm

Fantastic article, definitely adding Naples to our rescheduled trip in August 2022. As long as we are allowed out of New Zealand. Love reading your columns but does make me wish I could get to Italy sooner!!