Picinisco: Italy’s pipeline to Scotland is a gastro, rural wonderland only D.H. Lawrence could describe

PICINISCO, Italy – Every town in Italy has a piazza. Then there’s this village in the Apennine foothills. Piazza Ernesto Capocci is more than just Picinisco’s town square. It’s a stage for one of the best views in Southern Italy, marveled by a crowd that resembles the European Union at an aperitivo.

Even on a gray, drizzly November day I gasped at the gently sloping green hills, dotted with red-tile roofs and fields of grapes and olives, stretching to the mountains beyond. Wispy clouds hung so low over distant villages they looked like a sky of cotton candy.

In summer when people climb to this vista at 800 meters (2,625 feet), I’m told Renaissance painters couldn’t capture its beauty. These people have one thing in common besides a love for beautiful Italian sunsets and Italian country cooking.

Most have returned to a village that has been a pipeline to Scotland for nearly 150 years.

Standing in the piazza Thursday I met Cesidio Di Ciacca. While he sounds like he could be Picinisco’s mayor, or, at least, a cozy trattoria, he’s actually a retired corporate lawyer from Scotland. He is part of that Italian pipeline in which more than 60 percent of Scotland’s people with Italian heritage come from Picinisco, population 1,200, and Barga, a town in Tuscany of 10,000.

Nearby, the village of Atina fed Paris and Belgium. People from Casalattico went to Ireland. From Settefrati they went to the United States.

“This is a meeting place at the end of the road,” Di Ciacca said, scanning the view he hasn’t tired of after a million times. “It’s the most cosmopolitan place you can ever imagine.”

Why Picinisco?

Marina and I came here on a freelance assignment, and we never pass up a chance to explore rural Italy, especially a town I’d never heard of. We could’ve driven the 2 ½ hours from Rome and back on the same day. But why rush when we could crash in a 96-year-old B&B with a heavenly view and eat Cabernet and blue cheese risotto?

Picinisco is halfway between Rome and Naples, in the corner where the regions of Lazio, Molise and Abruzzo all converge. Abruzzo National Park is a bike ride away. On a clear day from the top of nearby 7,382-foot (2,250 meters) Monte della Meta it’s said you can see both the Tyrrhenian and Adriatic seas.

We drove east from Rome 75 miles, through the pretty Alban Hills past Frascati and all its vineyards. We turned off the autostrada at Frosinone and headed uphill along narrow rural roads through quaint villages and manicured farmland. The roads were lined with trees sporting fall colors of orange and red and purple and gold.

This is Valle di Comino, a collection of agricultural villages that produce olives, wine, livestock and some of the best high-end Pecorino cheese in the world.

On the corner of a windy road up the hill stands Villa Inglese. It’s more of a showcase for Italian architecture than a B&B. Painted in tints of salmon and gold, the three-story Art Nouveau home has two gabled balconies and a rooftop terrace with a view of the entire breathtaking valley.

A stone gate encloses potted flowers, ferns, lavender and an olive tree with the same palm tree planted when the home was built in 1926.

Owner Ben Hirst greeted us from his balcony. Tall and bald with a distinguished, salt-and-pepper beard, Hirst, 55, comes from a long line of English chefs. He left Wiltshire County, England, 30 years ago to explore new gastronomic adventures. He settled in Rome where he co-founded the restaurant Necci then came across Picinisco, an agricultural paradise which he said is “what I think Italian cooking should be.”

He bought Villa Inglese five years ago and opened it, as luck would have it, right before Covid hit in 2020. It opened and closed for more than a year before finally opening full time last spring.

“I love this house,” said his wife, Gaynor. “I love the feeling in this house. Everyone who comes has the same passion. The views are spectacular. I’ve traveled and this rivals anywhere.”

Villa Inglese is a direct result of Picinisco’s Scottish pipeline. Antonio Marcantonio was born in Picinisco in the late 1800s and moved to Scotland when he was a child. He grew up to own an empire of American-style ice cream parlors..

One time on his return to Picinisco, Tuscany’s Liberty-style Art Nouveau villas caught his eye. He found an architect to build a similar home here in his hometown. In 1926, Villa Inglese was born.

Marcantonio was part of the Grand Tour, the famed trans-European adventure wealthy Brits did in the late 1800s. It was also in the late 1890s when Italy, particularly in the South, was impoverished from political corruption and a failed military campaign in Africa. That’s when the first wave left Pitrinisco for Edinburgh, Scotland. At the time, Edinburgh was one of the wealthiest cities in the British Empire and Glasgow was the No. 2 city behind London. There was work aplenty and the Italians set up their own businesses, particularly ice cream such as Marcantonio’s.

After World War II, when Benito Mussolini’s ill-fated friendship with Adolf Hitler left Italy in ruins, came another exodus.

As they said around here, “You can’t eat the view.”

For more than 100 years, people have returned to Picinisco to discover their roots, to see long-lost relatives and see what they all left behind.

“We’ve had people here whose families went to work in the cotton mills in the 1850s,” Gaynor said.

Then there’s Cesidio Di Ciacca who returned from Scotland and bought a village.

I own I Ciacca

Di Ciacca’s says his ancestors in the village of I Ciacca, eight miles (14 kilometers) from Picinisco, date back about 500 years. Just like Leonardo Da Vinci, who’s from Vinci, Tuscany, the Di Ciaccas adopted their town’s name.

Cesidio was born in Scotland in 1954 and raised in Cockenzie, a fishing village outside Edinburgh. His father was born in Picinisco and his grandmother was born in London but raised in Picinisco. A grandfather was born in I Ciacca and as a child Cesidio frequently came to the village where he’d eat figs off trees other people shared with the town.

He sold his law firm in 2010 and increased his trips to this quaint little valley. I Ciacca has been emptying since 1850 and his memories of his relatives reminiscing of their village over Christmas dinner inspired him to make a bold move.

He first bought a four-story house in Picinisco which he turned into the six-bedroom Sotto Le Stelle hotel. He loved the area so much that he convinced the 140 landowners in I Ciacca to sell them their parcels. In 2013, he owned the entire village.

I asked what he liked most about Picinisco.

“Peace,” he said. “It’s a cosmopolitan village. In the summer you meet people from all over the world. D.H. Lawrence called this piazza ‘the drawing room of town.’ That was 1919.”

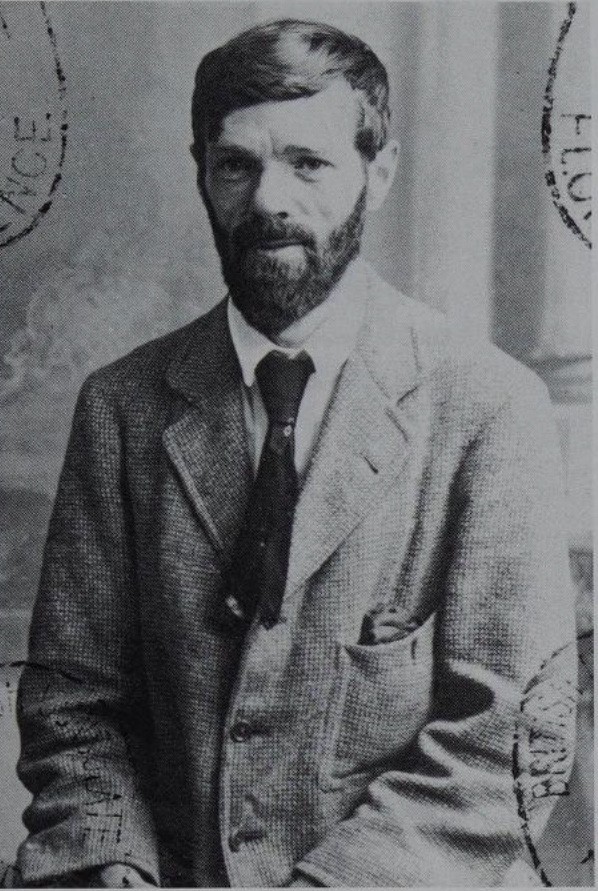

Oh, yes. Picinisco’s most famous resident: D.H. Lawrence.

Lawrence moves to Picinisco

Considered by some as the greatest British travel writer, Lawrence discovered Picinisco during his self-imposed exile in 1919. Accused of being a German spy during World War I, he bolted Britain and toured the world, from the U.S. to Ceylon (modern-day Sri Lanka) to Australia and much of Italy in between.

Already famous for his novel, “Sons and Lovers,” in 1913, he passed through Abruzzo in December 1919 and was invited to stay in this rustic farmhouse in Picinisco by a friend, a model named Orazio Cervi. He built it in 1889, a dream home with arched doorways and wrought-iron balconies. For two winter months Lawrence stayed in an upstairs bedroom and finished his hit novel, “The Lost Girl.” It won the James Tait Black Memorial Prize for fiction in 1920 and much of Picinisco’s surroundings are found in the book.

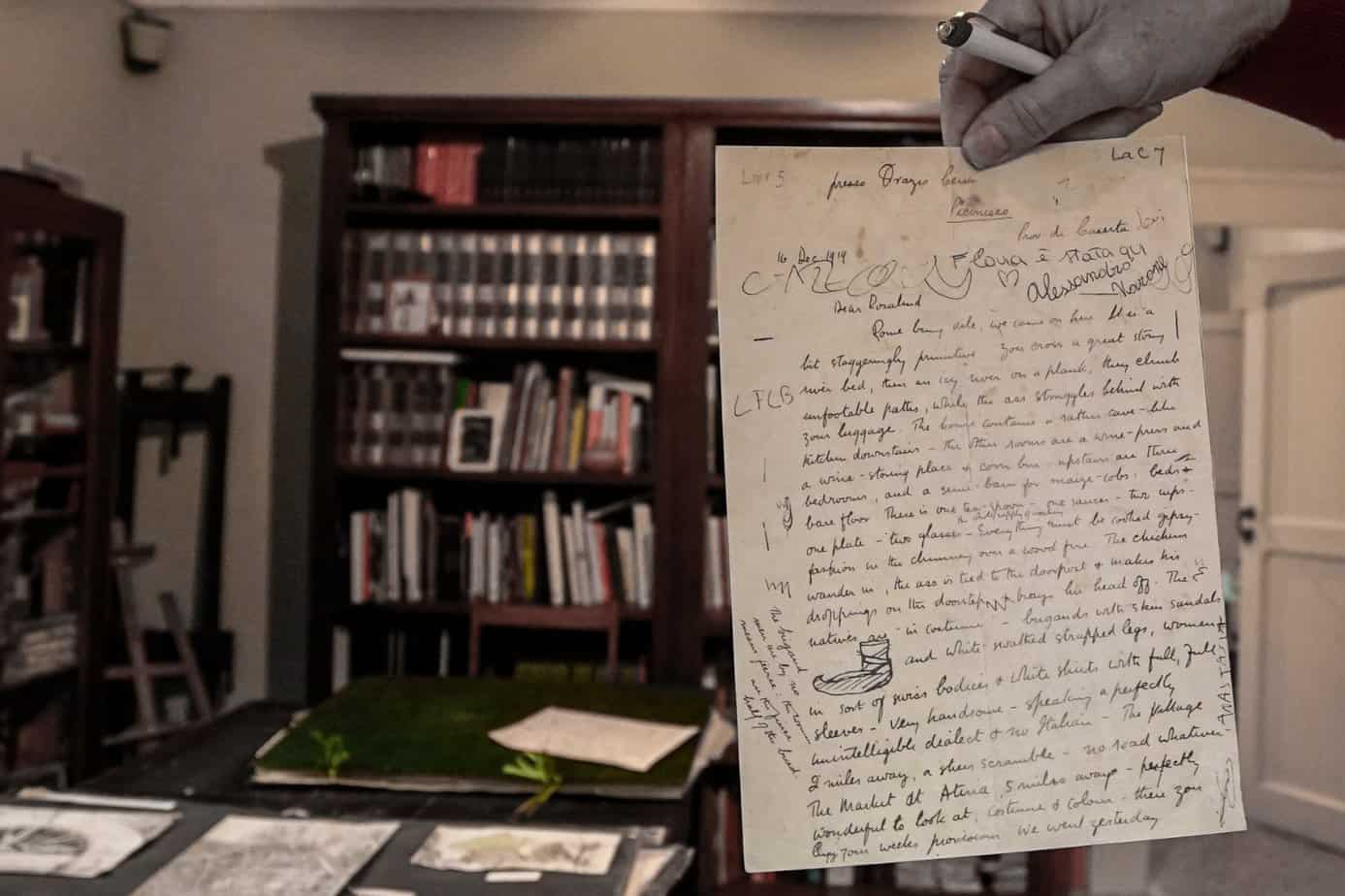

In the novel, he referred to Picinisco as Pescocalascio and described the area in the middle chapters. While admiring the beauty, he also called it “staggeringly primitive.” As he wrote of his visit:

“You cross a great stoney river bed, then an icy river on a plank, then climb unfootable paths, while the ass struggles behind with your luggage … The house is composed on the ground floor of a kitchen more similar to a cave … We have to cook over a fire and eat our food on our knees sitting on a bench in front of a gloomy kitchen fire.”

The house, now an agriturismo dubbed Casa Lawrence, has been modernized but the rooms have been decorated in the fashion that Lawrence described in the book. I toured the house and sat at Lawrence’s desk where he finished “The Lost Girl” while staring at a wall. The rooms are large with big beds. A vintage phonograph and an ancient manual typewriter sit in one room.

Outside I could see the rolling foothills of the Apennines covered in forest. Under olive and maple trees, I sat at a picnic table with Casa Lawrence owner Loreto Pacitti. A Picinisco native, he also runs La Caciosteria di Casa Lawrence where his Pecorino Picinisco is some of the best cheese I’ve ever had.

“I was born here and I want Picinisco to survive,” he said. “I love this land and I want the land and traditions to survive. I fight for them.”

Pacitti connects visitors with winemakers, olive oil producers, pizza makers and is creating a food network “just to protect and develop the economy of Picinisco.”

Villa Inglese

Covid leveled Picinisco as it did all of Italy’s agricultural areas. Villa Inglese opened and closed before finally opening full time last spring. Besides our comfy room with the balcony and million-dollar view, the night was worth it just for the food. As Hirst said, “The least-explored part of Italian cooking is the mountain cooking.”

To prove it, this is spread he laid out for us (by courses):

- A cheese plate with five different cheeses: Blu di Val di Comino, Marzolino, Pecorino di Picinisco, Marzolino Stagiondo, Conciato di San Vittorie. All were sprinkled with bits of pomegranates, hazelnuts and peppers from the area.

- Yellow pumpkin soup.

- Canapes: Pumpkin and baked ricotta tortelli pastry, Pecorino and black pepper pallotte, biscuits with pumpkin carpaccio and fresh sheep ricotta.

- Beetroot carpaccio in homemade cherry vinegar with pomegranate, quince jelly and marzolino.

- Risotto in local Cabernet Sauvignon and blue cheese sauce.

I asked Ben why he liked living here.

“It’s the food and the food culture,” he said. “You couldn’t get this in Tuscany. The butcher I go to, for example, he makes mortadella (pork sausage). He sells the mortadella to Emilia-Romagna. Emilia-Romagna is the home of mortadella but they get it from here. This whole valley is organic. I’ve never known products like this.”

In a country crammed full of dynamic scenery and equally delicious food, this little village of Picinisco still stands out. Like many Scottish who have returned over the years, I’d return here, too. I also have another reason to return besides views and food.

I’m a quarter Scottish.

If you’re thinking of going …

How to get there: Rent a car. The closest train station is at Cassino 18 miles (30 kilometers) away. Rental cars in Rome start at about €25 a day.

Where to stay: Villa Inglese, Via San Martino 22, 39-339-206-7574, www.villainglese.com, info@villainglese.com. Art Nouveau palace built in 1926 with incredible balcony and rooftop terrace views of Valle di Comino. Owner Ben Hirst is a professional gourmet chef who produces amazing meals with local, seasonal products. Rooms start at €95 breakfast included.

Where to eat: Caffe Cominium, 509 di Forca d’Acero, Atina, 39-347-707-0707, 6 a.m.-6 p.m. A modern restaurant in a rustic valley, it’s a casual lunch place with pastas, burgers and local wines at reasonable prices.

When to go: The valley has many food festivals. There’s an orapi (wild Italian spinach) festival in the beginning of May, a pastorizia shepherds festival in July and mushroom festival the first Saturday in October. Hottest month is August with highs in mid-80s and lows in low 60s. Coldest is late January (30-45). Our days in November were 50s and 60s.

For more information: Visit Italy website, https://www.visititaly.com/search-results.aspx?key=Picinisco.

November 22, 2022 @ 3:18 pm

I didn’t know Picinisco.

Thank you for your suggestion.

November 22, 2022 @ 5:25 pm

Love Picinisco, village of my ancestors.

(Nb, Lawrence was accused of being a spy during WW1, not 2).

November 25, 2022 @ 10:11 am

The family of my first boss, Ricky Demarco, second generation Italian Scot and Edinburgh art gallery owner, is from Picinisco.

January 20, 2024 @ 9:13 pm

My grandfather Lorenzo Marcantonio left Picinesco in 1880 to come to Edinburgh via London and Newcastle, where my dad was born in 1904.

The family is now in Ayr Scotland.

November 22, 2022 @ 5:52 pm

I will definitely go!

November 22, 2022 @ 9:36 pm

Was there two weeks ago, family from Atina with distant relatives from picinisco, lovely place.

November 23, 2022 @ 12:12 am

I have visited the house of the author DH Lawrence and savoured the culinary delights in the house next door where the owner is also the chef who presented us with his award winning menu. I couldn’t do it justice with my limited literary ability, suffice to say that it is an experience I will never forget.I have been in Picinisco number of times and will never get fed up with its quant beauty. I don’t have Any Italian heritage but I do have an extended family of cousins who make sure I see all there is to see when I visit the. Beautiful Val di Comino.

November 23, 2022 @ 9:44 am

We visited Picinisco, my ancestral home, for the first time in October this year. It is every bit as described in this article – and more.

November 23, 2022 @ 12:45 pm

I visited Picinisco last summer and had a fantastic stay at I Ciacca. The dining experience at Villa Inglese was also top notch. Highly recommended.

November 23, 2022 @ 5:09 pm

Both my parents are from Piccinisco and I spent every summer there as a child and teen. Haven’t been back since 2005, need to go soon

November 23, 2022 @ 5:49 pm

Ben Hirst does not own Villa Inglese, his partner (not Wife) purchased it.

Cesidio Di Ciacca is not a ‘retired’ Lawyer. The law company that he worked for MANY years ago ‘retired’ him.

D.H. Lawrence came to Picinisco on holiday for approximately 9 days. He had connections in London with an Artist’s Model from Picinisco who graciously accommodated him.

March 3, 2023 @ 1:32 am

This article s well written and captures well the village and the surrounding area. I don’t see the point of nit picking and embarrassing the author and the people he encountered on his travels.

January 19, 2024 @ 11:44 am

I too am a bit of a pedant. I’ve met Ben and Gaynor and stayed in Villa Inglese, enjoying the view from the idyllic rooftop terrace. A lovely couple – Ben is an artist as well as a magnificent chef and Gaynor’s breakfasts set me up for the day. I never discussed ownership since it’s nebulous and irrelevant. I know they both worked hard on the albergo and it has paid off. I have also stayed in Sotto le Stelle and met Cesidio to talk about history – he is knowledgeable. All three have a love of the town and I admire the way they have allowed their albergos to maintain their historic exteriors whilst bringing the inside up to the standard visitors – most of whom are of mature years – love.

November 23, 2022 @ 8:52 pm

Enjoyed the article, many thanks.

November 24, 2022 @ 1:03 am

The residual memory of place – molecular programming, a magnetic force that pulls the diaspora back to Italy. Heimat DNA for want of a designation, imagine trying to explain that to an Italian immigration official when you have no other credentials to remain in Italy.

November 24, 2022 @ 3:35 am

My grandfather, Orazio Cervi, built the house Lawrence stayed in, with the earnings from his lifetime’s work as a favored artists’ model in London through the later 1800’s and early 1900’s. Lawrence did not accomplish any significant writing whilst in Le Serre (in the Comune of Picinisco) as he was there for only a few days, where he was miserably cold in that “staggeringly primitive” mountain community. He did however, record his stay in the novel ‘The Lost Girl’, and represents Orazio (Pancrazio in The Lost Girl) as he must have appeared in his later years, repatriated back to Le Serre, near Picinisco, in that novel. I am one of Orazio’s many grand children and great grandchildren, many of whom remain proud of his adventurous and accomplished life. He is credited as the model for many fine works of art by Hamo Thornycroft, as well as by Frederic Leighton. It was Hamo Thornycroft’s daughter Rosalind Baynes who suggested that her friend Lawrence and his wife Frieda visit Orazio in the Italian village where she thought they might enjoy residing whilst in exile from England.

October 21, 2023 @ 2:26 pm

I believe Orazio was the model for two statues in Kew Gardens, the Reaper and the Sower.

November 24, 2022 @ 4:41 pm

Thanks John. Happy Thanksgiving from the Hudson Valley of NY from Lisa and me.

February 13, 2023 @ 5:15 am

My great great grandfather Francesco D’Ambrosio left Picinisco in the 1880s and settled in Hamilton Scotland. I have only recently finally figured out where exactly he was from. Trying to trace the rest of my family and hopefully walk in my acmcestors footsteps very soon.

September 8, 2023 @ 6:21 pm

We must be related Nico! My Great grandfather, Germiah D’Ambrosio left San Gennaro in the 1890’s, initially for Scotland.

January 19, 2024 @ 11:50 am

My Arcari were from San Gennaro … mostly settled in Manchester and London with twigs in Great Yarmouth and Paris … when I visited the frazione a couple of years ago I was asked on my return to Picinisco, “was anybody in?” It’s in a beautiful location. Michel de Vacca (Belgian) has transcribed parish records.

March 3, 2023 @ 5:17 am

My paternal grandmother was born and raised in iCiacca. Looking forward to returning this spring. It will be my fourth visit.

March 12, 2023 @ 4:01 pm

Brilliant overview – we are going to Picinisco this May / June 2023 to see where my wife’s Grand mother is from – she came to England in 1900 ( age 10 years ) and the family name is Tuzi.

We will update you with what & who we find / meet.

March 20, 2023 @ 10:26 pm

My great grandfathers family came from Picinisco. They ended up in Clerkenwell, London selling ice. Would love to go there one day. There name was Perella.

April 27, 2023 @ 10:05 pm

Familiar Alonzi celebrated the 100th Aniversary of the Shrine to Maria S.s. Di Caneto in 1988. You a see the ceremony that was held on my YouTube site. Type in “The Alonzi” and go to Videos then scroll down until you find the Video.

Feel free to view the others as well.

May 31, 2023 @ 10:12 pm

We too are related to Francesco Perella. we live in Newcastle upon Tyne UK and are trying to trace our family tree and hoping to travel to Picinisco soon!

October 21, 2023 @ 2:30 pm

George Marcantonio was from Picinisco and he founded Newcastle’s renown Mark Toney Ice Cream and coffee shops.

June 20, 2023 @ 12:17 am

I am from the Netherlands, my great grandfather Giuseppe Capaldi, also came from Picinisco, he was a well-known Italian fair family in the Netherlands, I am going to Picinisco for the first time this summer and see where my roots are, I am so looking forward to it!

July 10, 2023 @ 2:52 pm

Great article! My family have traced our ancestors, one of the Pacitti families, back to the town of Picinisco after leaving for Glasgow and finally settling in Aberdeen. We are visiting Picinisco in April 2024 and much looking forward to it!

We would also like to see the abandoned village of La Rocca near San Gennaro if there is anyone who can direct us to the place as I believe this is where our family were located.

July 12, 2023 @ 10:05 am

Ask around Picinisco. Someone will surely volunteer to take you there. Thanks for the note.

September 8, 2023 @ 6:16 pm

There is very little of the village of La Rocca left. I visited in October 2022 as my GG Grandmother (Faccenda) was from there. The village is relatively easy to find. Just drive up through San Gennaro – where my G Grandfather D’Ambrosio was born.

October 8, 2023 @ 2:04 am

my great grandma and Grandad come from Picinisco they where Pacitti we live in Gateshead Tyne and Wear

August 15, 2023 @ 3:48 am

Hi Chris

If you head for Casale it’s sign posted opposite the Villa Inglese keep going straight past Casalucra (Capaldi) past the cemetery you come to a t junction before Ponte American turn left….La Rocca is abandoned now but it was full of life when my Dad was young ,him and his friends loved going to La Rocca

Enjoy

August 15, 2023 @ 3:50 am

Hi Cindy my Grandad was also called Giuseppe Capaldi ,most ot the Capaldi Clan stayed at Casalucra

Enjoy your Trip

October 1, 2023 @ 4:34 am

My parents were both from Picinisco, but they didn’t meet until both were visiting the United States pre-WWII. My maternal Great-Grandfather is Irazio Cervi, a friend of D.H. Lawrence and original owner of Casa Lawrence. We visited Picinisco a few years ago and had a wonderful meal prepared by Loreto Pacitti. This travel story by John Henderson is as accurate a piece as I could ever imagine. Thank you for bringing my memories alive

January 19, 2024 @ 11:30 am

There were members of the Cervi family from Picinisco in Manchester, England around the 1920s, 30s and 40s

October 1, 2023 @ 5:09 am

Please correct my above typo:

Orazio

December 5, 2023 @ 5:45 pm

I believe my Italian grandmother was born in Picinisco. Her name was Teresa Rebecchini and she was born 2nd February 1877.

Her parents were Ignazio and Dominica Rebecchini.

I’m not sure when they came over to England but wondered if Rebecchini is a name local to this area of Italy?

January 27, 2024 @ 11:57 am

we are going to Picinisco in October to see if we can get birth certificates for my great grandma and great grandad their surname was Pacitti

January 29, 2024 @ 11:18 am

The world is not big enough to record all the extended families that originated from Picinisco Most families left for every continent and grew through “chain” migration .

Going ‘home ‘ on holiday showing successful business success fuelled this.