Plovdiv: Bulgaria’s Europe Culture Capital

(This is the third of a series of blogs on Bulgaria.)

PLOVDIV, Bulgaria — How old is an 8,000-year-old city?

In 6,000 B.C., much of the world still lived in hunter-gatherer communities. Crude Neolithic tools were first introduced to Europe. A massive volcanic landslide forever changed the Mediterranean coasts of Europe, Africa and Asia.

Also wine was invented so I credit that era for saving the future of mankind.

Imagine a city that lasted through all that. Now imagine it today, thriving as one of Europe’s cultural capitals with one of the most vibrant art scenes for its size in Europe.

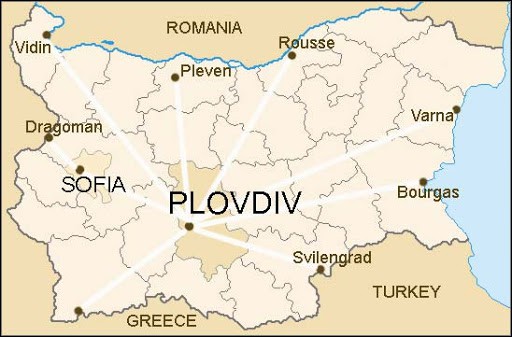

That’s Plovdiv. It’s Bulgaria’s second-biggest city but now likely it’s No. 1 tourist attraction. It forever became etched in the itinerary of every intrepid traveler when the European Commission named it one of two Europe Cultural Capitals for 2019.

The other was Matera, Italy. It claims to be 9,000 years old and the third oldest continuously inhabited city on earth. Plovdiv claims it’s the oldest in Europe. I’ll let the two duke it out. Maybe they can use Plovdiv’s Roman Amphitheatre dating back to the 2nd century A.D. Why not? If it’s good enough for Sting and Tom Jones to perform, it’s good enough for the two cities’ aggressive PR departments.

However, artsy Plovdiv is too laid back to get upset about much. It has lifted Bulgaria’s 31-year-old democracy to a new level of bliss. Few places I’ve been in Europe have the same relaxed vibe as this former backwater wait station between Bulgaria, Greece and Turkey. People drink craft beers on cobblestone alleys left by the Ottomans, stroll the longest pedestrian street in Europe, sit atop the hills and gaze at the surrounding Rodopi Mountains.

Said Bulgarian writer Filip Gyurov of Plovdiv: “People, especially young people, have experienced the awful side effects of burnout. Hence the need to slow down, to de-grow, to live more in sync with nature and ourselves.”

The journey

I arrived off my first of many bus rides, the preferred mode of cross-country transportation in Bulgaria. Sofia’s Central Bus Station is a massive relic from communist times with “SOFIA CENTRAL STATION” in huge imposing letters that, not subtly, make the people feel small.

A small gaggle of people stood outside dirty ticket windows then stepped into the adjacent cafe to drink strong Turkish coffee and fresh pastries straight out of the oven. My expected large, luxury bus I’d read about instead turned out to be a very large van. My knees ground into the back of the seat in front of me. It felt stuffy despite the mild temperatures in the mid-70s. The windows wouldn’t open.

The good news is air-conditioning came on after we left Sofia and the 2-hour, 15-minute ride 90 miles east was only 10 leva (about 5 euros). Did I tell you Bulgaria is cheap?

With a “Planet of the Apes” sequel playing on the small screen up front, I stared out and watched Sofia’s sea of concrete, communist-drab apartment buildings give way to a tree-lined highway. Wisps of morning clouds hovered in the surrounding green hills.

Upon arrival, my scruffy-faced, elderly Plovdiv cab driver had no clue where my hotel was. I showed him the address in Old Town, which in an 8,000-year-old city means real old. He asked directions twice, got stuck down a narrow alley of huge, crude cobblestones and nearly caused a three-car pileup spending 10 minutes just turning around.

Clueless cabbies would be a recurring theme in my week-long journey through Bulgaria. The dilemma seemed especially exasperating since my hotel is arguably the most famous in Plovdiv. The Hotel Hebros is a 250-year-old mansion that once was the place to stay for visiting furriers during pre-revolutionary times and later heads of various communist states. I could imagine them feeling very royal in the elaborately decorated rooms with antique furniture and gold drapes.

I did.

Unfortunately, the Hebros was going through post-pandemic renovation and the reputably terrific restaurant in the open-air courtyard had closed as well as the Jacuzzi and sauna.

I survived across the street at the corner Satori Magic Cafe, a tiny hangout covered in potted plants. I wrote on little tables while locals munched baked goods on padded benches. The June temperature was in the 70s. A soft breeze came down from the Rodopis. By 10 a.m., sunny Plovdiv felt like a medieval village in the Abruzzo highlands.

The tour

In Plovdiv, you can cover 8,000 years of history in about a 45-minute walk. I started out on its mile-long pedestrian mall which blends into the Ottomans’ old warehouse district and then crosses under a major thoroughfare into Old Town. I never encountered a car. Plovdiv is like Venice with less boat traffic.

After a wonderful Sofia Walking Tour, I took that mode again with the Plovdiv Walking Tour. We met at the Plovdiv Municipality, the city hall in a beautiful baroque palace with two Doric columns holding up a balcony in front of three tall windows. It sits in a big square with lush green grass at the start of the pedestrian mall. Behind city hall are columns and stone foundations from the old Ancient Roman settlement.

Meeting about a dozen of us was Illiya Iliev, a husky, 24-year-old Plovdiv native with thick, jet-black, combed-back hair and the enthusiasm of a puppy. I told him I lived in Rome and he said the two cities have something in common and not just that Plovdiv was a thriving Roman town in the 1st century A.D.

Plovdiv also has seven hills. Well, it did. When the Ottomans built up the city, it received permission to pummel one of the hills for the granite that we would walk on all day. Decades ago the city did more damage than the Ottomans ever did. In the spot where the hill was, the city built — gasp! — a shopping mall and parking lot. However, eight years ago a local artist took stones from the old site and inscribed lines of poems from the city’s poets. He placed them in a pile next to Plovdiv’s mosque for its makeshift seventh hill.

We strolled down the spotless stone pedestrian street that seemed as modern as the one in Copenhagen, No. 2 on the list. Built 100 years ago and renovated in 2007, the street is so long it has three names. It also sports many tony retail shops and eateries and flower planters hanging from lampposts. A woman entertained children with a marionette not far from the ubiquitous human gold statue. A violinist trolled for coins by having his dog bark in tune with the passable music he played.

It was gloriously comfortable. We encountered no other tour groups. The sidewalk restaurants weren’t crowded. Shops were just reawakening from the crunching pandemic blitzkrieg.

“Tourists haven’t shown up yet,” Illiya said.

They did in 2019. Similar to Matera, Plovdiv put on a year’s worth of exhibitions, from art exhibits to concerts in the amphitheatre. Plovdiv experienced a 27-percent increase in foreign visitors from the year before. In fact, 1.2 million visitors came from elsewhere in Bulgaria. That’s 22 percent of the country’s population. It recently made Financial Times’ “Top 10 of the most progressively developing places in the world.”

Wrote Plovdiv 2019 Foundation chief Victor Yankov in an email: “Working nationally and internationally, using the momentum and the driving force that this large-scale European brand carries, we increased the popularity of Plovdiv and positioned it as a cultural, tourist and investment center.”

At the end of the street was a model of a near replica of Rome’s Circus Maximus. This one held only 35,000 people but it had the same oblong shape with grandstands around three-quarters of the stadium. Built by Emperor Hadrian in the 2nd century A.D., it was 240 meters long and 50 meters wide. An archaeological dig in 2016 found animal bones and weapons, proof that they had gladiator battles and animal slaughters, similar to the Colosseum.

The stadium still exists today under the street. Iliya said you can walk into the Excelsior, Plovdiv’s first cinema, and the H&M department store, go into the basement and see part of the stadium.

We walked past a small open-air amphitheatre and came by Plovdiv’s mosque. The Dzhumaya Mosque’s lone minaret sticks up above the modest skyline like a sparkler. Built in 1364 by the Ottomans, the building was leveled and rebuilt in the mid-15th century in the red brick and white granite Byzantine style. It’s different from most mosques which are perfectly square. This one is rectangular. Of Plovdiv’s 500,000 people, 8 percent are Muslim, 5 percent Catholic, 4 percent Jewish and 1 percent Christian. The rest are Orthodox Christian.

I asked him about the religious tolerance the people in Sofia boasted.

“We are a people of faith,” he said. “We are not a people of religion. We have a Protestant community and a Jewish community and a Turkish community and an Armenian community and a Catholic community. But we have no ethnic neighborhoods. We’re all mixed together. That’s what makes it so attractive.”

We couldn’t go in. Illiya, showing good sense, said he won’t disturb praying Muslims with a large tour group. Too bad I stayed only one day. I wanted to enter just to see a mosque with a cafe. True. The Ottomans built a cafe inside.

“The Turks never fail to remind us that they brought coffee to Europe,” Illiya said with a smile.

We turned another corner and the streets became narrower. The cobblestones became smaller. Nothing was wide enough for cars even if they were permitted. Inviting bars and restaurants and umbrellas over table settings dominated both sides of the streets, all decorated with potted plants of red and yellow flowers and trees in full foliage.

This is Kapana. The name is the Turkish word for “trapped” and the Ottomans built their marketplace here in the form of a maze. That way, the more people got lost, the more stores people would pass and the more they’d buy.

“Like Ikea,” Illiya said.

Then came a period of decline and revival. In 1818 the Ottomans didn’t need a marketplace anymore and it was abandoned. In 1906, two years before Bulgaria declared independence from Turkey, the whole neighborhood, made entirely of wood, burnt to the ground. It was rebuilt and became an industrial area. People had their tobacco factories on the bottom floor and they lived on top.

But under communism, the government took over all the businesses “so we’d all get a piece which never happened,” Illiya said.

Everyone lost their businesses and left the area. It remained a desolate, dusty, dirty place all through communism and hadn’t changed in 2014 when Plovdiv received the 2019 Europe Culture Capital title. Why did they give Plovdiv the title with such an eyesore?

“They gave it not based on what your city looks like now but its potential,” Illiya said.

They gave Plovdiv five years to clean it up. The city offered artisans free rent for a year and they flooded the area, turning Kapana into Plovdiv’s first art colony. The European Union provided funds that were highly regulated “and didn’t end up in the wrong pockets,” Illiya said.

However, as the area improved, rent became higher. When the year expired, the artists bolted. In came Bulgaria’s new entrepreneurs to open bars and restaurants.

The new artists attracted to Kapana were street artists. They painted the sides of buildings and turned the neighborhood into an outdoor art gallery. Businesses competed for their work. I passed one wall covered with an angry man in mid-scream breaking chains around his mouth. Under him are the English words “THE CHAIN ROCKERS.” It’s a portrait of free speech and a symbol of Plovdiv’s new future.

“Most people will tell you that Bulgaria is still in a period of transition even 30 years after the fall of the socialist period,” Illiya said. “As far as I know many countries that have had the transition are a bit ahead of us, but our economy is getting better, slowly but steadily in a good direction, so we need to continue like this with our future politicians as well.”

We then crossed through a thoroughfare underpass and walked up the steep rocky street — and found ourselves in front of my hotel. This is Old Town where a 4th century B.C. gate still stands up the road from the Hebros. Locals filled my little Satori Cafe.

Here is where we ventured into the back of beyond of Europe’s history. It was on this hill where remains of settlements that date to 6,000 B.C. were found. The warrior tribe Thracians set up shop here in 5,000 B.C. building a castle called Eumolpias.

Philip II of Macedonia, the father of Alexander the Great, conquered most of Bulgaria in the 4th century B.C. and named the city Philippopolis, after himself which explains why he christened his son as Great.

After a major cloudburst right out of the Amazon Jungle, we continued up the hill to some huge, oddly shaped houses. The second floor was wider than the first, and the third was wider than the second. During the time of the czars, citizens were taxed by the amount of ground space the house occupied. The law said nothing about how much space the building occupied. Thus, people built larger second and third floors, giving the neighborhood kind of an upside down look.

We ended the tour under threatening skies at Plovdiv’s most famous site. Atop a hill with a pretty view of the city below and the surrounding mountains stood the Roman Amphitheatre, a UNESCO Heritage Site. It wasn’t discovered until 1968 after an earthquake and was excavated for 10 years.

On this rainy afternoon, at the tail end of a pandemic, black seat pads were scattered about. Amplifiers covered in plastic gave it a messy, yet more authentic look. I could imagine how beautiful any performance would be from a top seat with the lights of the stage in the foreground and the twinkling lights of town beyond.

After traveling through 8,000 years of history, I was starving. I continued my delicious gastronomic tour of Bulgaria by taking Illiya’s recommendation. I returned to Kapana and found The Brick Road, famous for its meat and pork. I had a sizzling steak with a Bulgarian red wine. That night I stopped at Mayriges, a Lebanese restaurant run by a Beiruti and his Bulgarian wife, and had saraya, a Middle Eastern bread pudding made from ashta, a rose-flavored clotted cream, white bread, syrup and crumbled pistachios. It’s like a lighter baklava and wonderfully refreshing served cold.

The next morning I returned and had breakfast at Pastry Shop Dzhumaya where I had a big brick of burek, Bulgaria’s famous cheese pie. Only two other tables were occupied.

The art scene

Plovdiv’s art scene goes back before World War I when the newly independent Bulgaria sent its most famous painters to Italy, France and Germany to study. Today the Open Art Foundation takes Bulgarian art all over the world. Every September an event called Night/Plovdiv has galleries, museums and bars open after hours.

Plovdiv seemingly has as many art galleries as gas stations. There is the Balabanov House for contemporary art, the Atanas Krastev House showcasing the famous local painter’s works, the Zlatyu Boyadjiev Gallery with 72 of the local artist’s pieces with an emphasis on Bulgarian peasantry, the City Gallery of Fine Arts with 7,000 works from the 19th and 20th century and the City Art Gallery which has temporary exhibitions. Plovdiv is a culture vulture’s feeding trough.

On my day, I was interested in going back 2,000 years again. Katya Staykova, public relations director for Plovdiv’s thriving Trakia Economic Zone, picked me up in her black Mercedes. Bouncy and fiercely proud of her city, she took me to Plovdiv’s latest pride and joy.

Bishop’s Basilica is in a modest, modern building on a major thoroughfare. Inside is artwork that dates to the Roman Empire in the 4th century A.D. but wasn’t open to the public until April 18. Bishop’s Basilica is a former Christian temple consisting of two floors covering 21,000 square feet. On those floors, one of which is 83 meters long, are millions of mosaics, still shiny and bright. Golds. Reds. Oranges. Greens. Blacks. Whites. It’s a kaleidoscope of colors.

There are more than 100 different birds in the mosaics ranging from love birds to songbirds. It wasn’t discovered until 1982 when the city built the thoroughfare. Through the America for Bulgaria Foundation, Plovdiv Municipality and Bulgaria’s Ministry of Culture, the restoration began in 2014.

Afterward, Katya drove me into Kapana to a big two-story house. Inside the house built in 1960 is the private art collection of Dimitar Georgiev, a cosmetic engineer and producer of Bulgaria’s expensive rose oil and arguably the country’s biggest art collector. Opened March 3 on Bulgarian National Day, the gallery features 380 paintings from his collection of more than 1,000.

War scenes. Portraits. Landscapes. They include works from George Papazoff (1894-1972), a Bulgarian who settled in France and considered one of the frontrunners of Surrealism. Also included is Jules Pascin (1885-1930), born Julius Pincas, a tragic genius who settled in Paris but committed suicide at age 45.

He would’ve loved this gallery. He would’ve loved this Plovdiv.

The goodbye

I ended my inexcusably short stay in Plovdiv the next morning at the Regatta, Plovdiv’s world-class rowing venue. I sat at the Landmark Hotel’s patio staring out at the manmade lake surrounded by trees and had a lovely salata shopska, a Bulgarian diet staple similar to a Greek salad.

Reflecting back on a remarkable 24 hours, I remembered twice visiting Matera, Plovdiv’s European cultural rival. Matera, though in my beloved Italy, is a distant second to Plovdiv in visitor appeal. Matera’s Old Town still looks like Old Jerusalem but Plovdiv hits every traveler’s trigger point. Walk a direct line through 8,000 years of history and finish at a sidewalk cafe looking at backlit Roman ruins with the shadows of surrounding mountains in the distance.

The ancient Thracians chose this spot well. So did the European Commission.

July 7, 2021 @ 9:17 pm

Wonderful John!! Thank you

July 8, 2021 @ 4:34 am

Great read! Thank you! 🙂