Retired in Rome Journal: Caravaggio’s final resting stop a great resting stop for the living

MAY 4

PORTO ERCOLE, Italy — He’s represented by a small white statue. His mouth is in a full-throttle roar as if he’s about to kill a man — the reason why Caravaggio’s image is in the middle of this pine forest near a beach in Tuscany. For all of the household names who have come from Italy’s artistic history — Leonardo DaVinci, Michelangelo, Bernini — of all those artists I’ve marveled at while living in Italy, Caravaggio has wowed me the most. It’s why I came to a tiny spit of a peninsula sticking out into the Tyrrhenian Sea to see where one of history’s greatest painters breathed his last breath.

To follow in Caravaggio’s final footsteps, I went up the Tyrrhenian coast with my good bud, Alessandro. He’s a fellow sportswriter and — literally — a Renaissance man. Like myself, he has been a long-time worshipper of Caravaggio and a foodie who could drive to Tuscany and eat every day if he could. On the 90-minute drive, we swapped stories of our favorite paintings and why Caravaggio inspires us — in between Alessandro rants about how the construction of another lane on the autostrada is raping the Italian countryside.

Unlike previous Renaissance artists who draped themselves in religion and groveled at the foot of the Catholic Church, Caravaggio was a rebel. He was a brawler. He was a womanizer, a partier. He was accused of theft. He was jailed numerous times. I admire him because he stuck to his own religious beliefs — or lack thereof — and threw tomato sauce on the church’s otherwise pristine canvas. Born Michelangelo Merisi in Milan in 1571, he took Realism to a new level. His “religious” paintings were shocking in their violence.

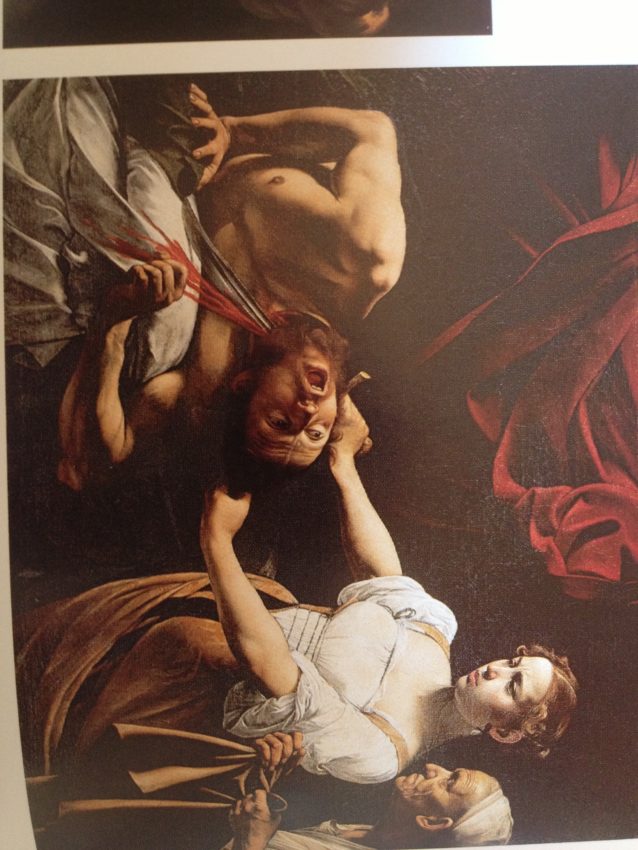

His “Judith and Holofernes” shows a servant girl, with the exact face of one of Caravaggio’s favorite models, cutting off the head of Holofernes. He was an Assyrian general who wanted to destroy Judith’s biblical city of Bethulia but not before shtoinking Judith first. Her sword is halfway through his throat. Blood spurts out like a fire hydrant. His eyes are looking at her as if to say, “Was it something I said?” Standing nearby is an old servant woman, wearing a vicious frown and carrying a sack to carry off the head. His “Flagellation” shows Jesus tied to a marble column and getting flogged by two muscular men wielding long, leather whips.

These are not the kind of paintings you normally see in the Sistine Chapel.

But Caravaggio’s genius was his use of shadow. Called “The Master of Darkness,” Caravaggio’s paintings all seem backlit. One light comes through a lone window to lend an eerie tone to all his work. The detail is astonishing in its clarity. One of his famous pieces, “The Vocation of Saint Matthew,” shows a group of men sitting at a table listening to two others standing and debating. Each face is perfectly sliced by the shadow from the shaft of light coming through an unseen window. It’s truly remarkable. You don’t have to appreciate art to appreciate this skill. I challenge any unemployed iron worker or mutant linebacker to look at a Caravaggio painting and not come away impressed.

For years I had a beautifully framed print of his “Madonna and Child with St. Anne” hanging in my condo in Denver. It shows the virgin holding a naked infant who is crushing a snake, the symbol of evil, under his foot. Standing nearby is St. Anne, looking old, wrinkled and, well, how Caravaggio thought she would likely look at that age. As I said, he took “Realism” to a new level.

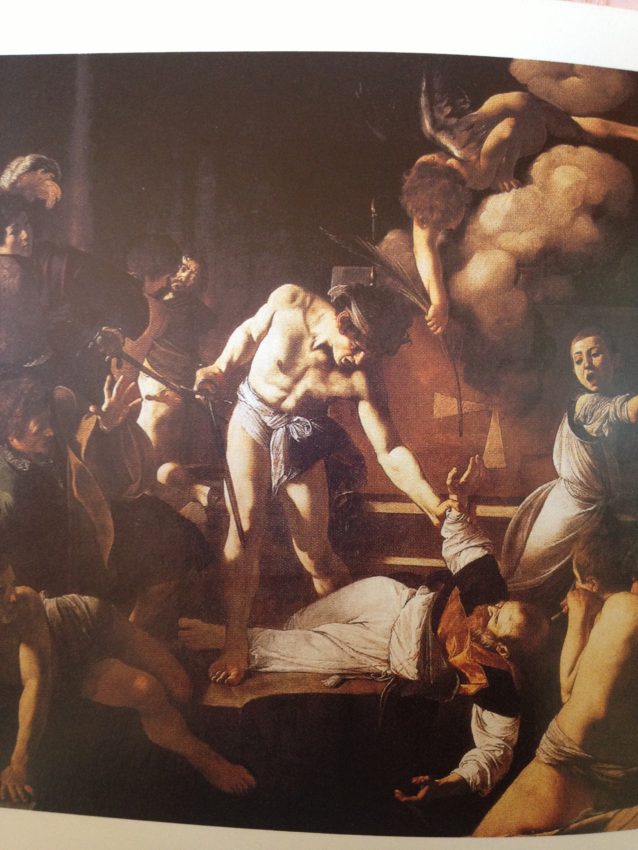

When I moved into my spacious apartment in Rome in March, I went to an art store near Piazza Navona and bought a giant print of “The Martyrdom of Saint Matthew.” Matthew was an evangelist who denounced the King of Ethiopia for lusting after his own niece, a nun. The painting depicts a soldier, on the orders of the king, grasping Matthew’s outstretched arm right before gutting him with a razor-sharp sword.

I figured that would look better in a man’s apartment than one of Caravaggio’s other works, such as a little boy holding a piece of fruit.

Unfortunately, like many geniuses, Caravaggio was a little nuts. His “Martyrdom of Saint Matthew,” seen in the Chapel in San Luigi dei Francesi in Rome’s Centro Storico, helped launch his fame. He fumbled much of it away by drinking, womanizing and brawling. The church rejecting some of his works for the sheer grotesqueness of them probably didn’t help his disposition. In 1606, he killed a man during a game of pallacorda, sort of an ancient form of handball, in Campo Marzio, next to where my former cell phone company’s office now stands. Sentenced to death, Caravaggio fled Rome then got in a fight in Malta and another in Naples. He was on a boat up the Italian coast in 1610 when Pope Paul V, on the urging of Caravaggio’s adoring fans, pardoned him. He never knew. He died not far from where I stood on a sandy, debris-strewn beach in Porto Ercole. Many said he died of malaria. Some said he was murdered. Researchers in 2010 claim DNA showed his bones had lead poisoning from his paints and he may have gone mad.

Before walking in his final footsteps, we had to eat. Alessandro, who knows every great restaurant not found in guidebooks, drove to the nearby hilltop village of Magliano in Toscana. This area is famous for its cinghiale (wild boar). These giant, tusked pigs roam the pine forests of the countryside and 100,000 Tuscans have licenses to kill them. As we walked to a restaurant famed for its cinghiale, we passed a group of hunters having a caffe outside a bar. You’ve heard of chicken cacciatore? “Cacciatore” is Italian for “hunter.”

Ristorante da Sandra is an elegant restaurant with white tablecloths and one of the best deals in Italy. For 25 euros (about $34), we got a six-course meal: appetizer of pappa all’pomodoro made with bread, basilico, olive oil, garlic and tomatoes; tortelli, a form of ravioli, filled with potato and black truffles; gnocchi with porcini mushrooms and pumpkin sauce; pappardelle, a flat, thick pasta, with wild boar sauce; fat chunks of wild boar in gravy made from local Morellino di Scansano red wine; and, finally, pork fillet in a puffed pastry crust. We finished eating at 1:30 p.m. and I didn’t eat again until the following breakfast.

I think I grew tusks by the time we left mainland Italy and drove down a narrow road connecting it with what seemed like a teardrop of an island where Porto Ercole occupies one corner and the larger Porto Santo Stefano occupies another. We walked through a forest of towering majestic Mediterranean pine trees. A female ranger giving us directions said they’ve seen wild boar wander through these woods during the day. The beach is a disaster. Italian authorities don’t clean up the debris washed ashore from the sea until mid-May when the tourist crowds grow.

But the town of Porto Ercole is right out of Hollywood. If the Pirates of the Caribbean had a five-star escape, this would be it. All that’s missing are palm trees. Porto Ercole wraps around a gorgeous harbor lined with port-side bars, restaurants, crafts stores and high-end apartments. The Spanish, whose empire was expanding throughout Europe in the 16th century, built forts on facing hills above the town. The views are quite stunning — and so must be the rent for the apartments that are now taking up space in one fort where ammunition was once stored.

It was pirates week when we arrived. It’s Porto Ercole’s salute to its past when it was indeed a popular site for pillaging and plundering in the 16th century. Locals dressed up in their most elaborate pirates outfit. One guy wore a blonde curly wig past his shoulders which couldn’t have helped his rowing ability during the annual sailboat race that we stumbled upon. About a dozen teams rowed little boats to small sailboats docked offshore. They were to hoist the sail and go around Porto Ercole to a small offshore island. They were to dock, run to the top of the island, grab their team’s banner, race back and sail back to shore.

The teams crashed their oars and hapless sailors fell into the water. Others struggled to move an inch on the deathly still, sunny afternoon. Meanwhile, Alessandro and I watched from a harbor bar. We raised a toast to Caravaggio, Porto Ercole’s true pirate, its true rebel. At 38, he died too soon.

Not far from us, in a dark forest few really see, Caravaggio is captured for eternity, imprisoned by a silent scream.